Tripping Together

As psychedelics are integrated into mainstream medicine, experts weigh the benefits and costs of solo versus group therapy.

by

Zoe Cormier | NEO.LIFE | 3 May 2022

With psychedelics being slowly decriminalized and major medical organizations increasingly exploring their value for mainstream health care, every day I get a dozen press releases from a dozen new startups eager to tell me about their new compounds, their special patents, breathlessly asking if I’ve ever heard of “psychedelic therapy” and wondering if I’d like to speak with their CEO to learn more.

The fact that these chemicals (which, keep in mind, are still illegal) have been transformed of late from contraband poisons into venture capitalist darlings is weird.

However, nearly every news announcement focuses on the chemistry—an oxygen atom added here, a carbonate group moved there. Few mention the obvious missing factor: how these drugs are taken and who gives them to you. But it is precisely that human element that determines how a psychedelic experience will go: whether it will lead to profound healing, just a nice afternoon, or a deeply traumatizing experience.

“The problem is, there is no ‘Big Therapy,’” jokes psychiatrist Josh Woolley of the University of California, San Francisco, making a reference to “Big Pharma,” the industry that drives the development, marketing, and sales of new drugs. This is an industry bent on a very private form of ownership—one that “discovers” or creates new compounds, protects them through proprietary patents, conducts expensive clinical studies, and publishes headline-grabbing announcements every step of the way to drive sales and recoup investments. But proven yet less product-oriented treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy rarely garner the same attention. Simply put: You can patent a new chemical, but you cannot patent a new human connection.

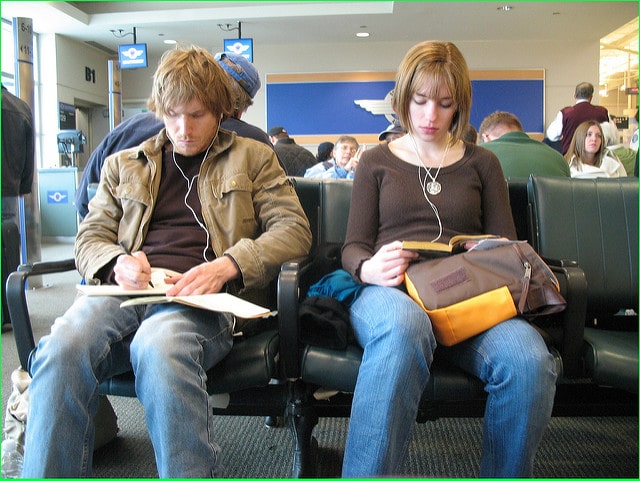

Yet experts say the two go hand-in-hand. Human interactions in psychedelic therapy have just as much if not more of an impact on the outcome of your therapy as the drugs themselves. Most psychedelics such as LSD and psilocybin (the active ingredient in magic mushrooms) act on serotonin 2A receptors in the brain, and the net effect is roughly the same (amplified emotions, ego dissolution, visions). But who you take them with and where—a therapist you trust in a clinic, your friends you adore in your home, or thousands of sweaty strangers at a rave—will lead to vastly different experiences and outcomes.

“Psychedelics are non-specific amplifiers, but communicating that is difficult because we live in a culture in which drugs are seen as something that act on you in a very specific way, which is possibly due to some degree of proselytism to our psychiatric culture that sees drugs as cures, and contexts as secondary,” says Christopher Timmermann, a neuroscientist in Imperial College London’s Psychedelic Research Group and collaborator on the paper.

Magic in the air

Going back to the 1950s, therapists spoke of the importance of “set and setting” in the earliest psychological experiments with psychedelics—the “set” being your emotional condition that you bring to the experience, and the “setting” being the environment. The model setting for guided therapeutic dosing that most academics and therapists are endorsing today is the same one that emerged more than half a century ago: Drugs are administered by a clinician in a dimly lit, quiet room with the patient blindfolded and listening to music, with one or two therapists there for hand-holding, words of comfort, or emergency support.

In all the research on depression, PTSD, and addiction that employ this model, the results are impressive. But that’s not how most people take psychedelic drugs out in the wider world and in the underground scene—what researchers call “naturalistic settings,” such as illegal weekend

ayahuasca ceremonies in the United States, or legal psilocybin retreats in the Netherlands. In such places, people take them in groups—often in large groups, up to 30 people at a time. Moreover, indigenous cultures with shamanic traditions who have used these compounds for thousands of years, from the North American Huichol peyote ceremonies to African Bwiti iboga rituals, have

always used them in groups.

“What is happening in academic institutions—the mainstreaming of these compounds—is dependent on the requirements of the institution, and doing group therapy at a clinical center is almost inconceivable, while individual therapy fits institutions more easily,” says Leor Roseman, who works alongside Timmermann at Imperial College.

“But those institutions didn’t invent psychedelic therapy, and their work is ultimately fueled by what’s going on in the underground.”

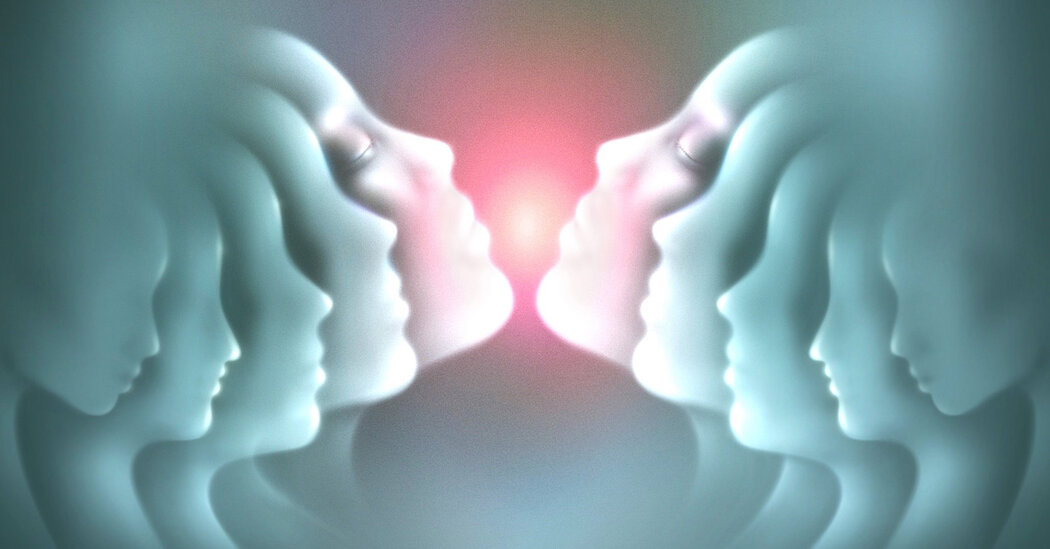

In the first study of its kind, they decided to look at data from such “naturalistic settings,” gathering feedback from nearly 900 anonymous people on how group experiences led to a variety of sensations that would never happen in the solitary mainstream therapy model, such as “emotional synchrony,” “identity fusion,” “self blurring,” and “collective effervescence.” Timmermann and Roseman and lead author Hannes Kettner, a PhD candidate at Imperial College London describe this phenomenon in a paper published earlier this year in

Frontiers in Pharmacology as “

communitas,” which Kettner describes as,

“an intense experience of togetherness based on basic shared humanity that transcends social structures.”

It’s the distinct kind of togetherness you feel at raves, protests, rallies, concerts, sports events. Something powerful happens when you experience those things in huge groups but never alone.

“People frequently say, ‘it was as if there was magic in the air’,” adds Roseman.

“This isn’t just about completely dissolving into the collective, but more about how an individual retains their specific identity and specific beliefs within a collective spirit and identity,” elaborates Kettner.

“It can do wonders—opening up to strangers can be a powerful experience.”

Or as co-author Timmermann puts it,

“Group experiences can help get us away from the culture of the self that we live in, the over-importance on the ‘me, me, me.’”

And the data suggests this really can have long-term beneficial effects.

Plant medicines and charlatan shamans

Unfortunately, I just don’t enjoy the group experience—if anything, I hate it. If I need to go inward to address deep issues, hearing other people suffer, vomit, and scream does nothing for me.

And on a few occasions, it’s been profoundly awful. In one ayahuasca session, a psychedelic brew-drinking ceremony led by a “shaman,” a woman became convinced that she could not breathe (she could). As a child, I suffered a rainbow of respiratory illnesses. So hearing somebody scream they could not breathe was more than a bit triggering. Thankfully I didn’t have a bad trip—but it did snap me sober.

Fifteen minutes later I experienced an allergic reaction to the shaman’s cat, which I didn’t know would be there, and again I not only snapped sober, and I couldn’t breathe (in actual reality, not my hallucinations). So I had to sit outside for the rest of the night. Which was in many ways preferable although the entire experience provided no healing, no joy, just annoyance—and a £200 hole in my wallet.

My verdict: “Plant medicines,” thumbs up. White charlatan “shamans,” thumbs down.

The final nail in the coffin of the group experience for me came in 2019 in the Netherlands. I thought the group experience would once again be too disruptive and chaotic for me, but I figured I’d give it one more try. As expected: Some people, who had never taken mushrooms even once before, freaked out. It was hard. There was lots of random wailing. One woman just sobbed on a loop, over and over, about how much she missed her father. But the most alarming was an Italian woman in her late 40s, who screamed and cried and thrashed until two guides carried her from the room and put her to bed.

The next day, she was completely fine—perhaps even better. Her freak-out had ruined my trip, but for her it was meaningful. She confided to us that she had suffered from an eating disorder for thirty years, and in her psychedelic visions, all she could see were pictures of food. Beautiful, lush, enticing images of food. And all she could think was,

“I have wasted my entire life not enjoying this crucial part of the human experience.” It was a breakthrough despite her difficulty. As psychedelic therapists often say, it’s better to describe “bad trips” as “challenging trips.” Even if the visions are unpleasant, the insights can be gold.

Her visions were fascinating to hear about. What was not fascinating to hear was a 30-year-old tech professional from Manhattan rant about how he’d come to the retreat to consider if his true calling was in marketing, or if he needed to pivot to another sector. It took every ounce of self-restraint I have not to scream,

“Some people have REAL problems.”

By contrast, the most beautiful, cathartic, and healing experience I’ve ever had with a psychedelic occurred when I was totally alone. No sitter, no therapist, not even a roommate. Alone. Dosing alone is considered profoundly unorthodox, goes against the grain of all therapy models, and is definitely not for the inexperienced. But for me it was perfect: An experience that, when combined with my expensive, disappointing, and ultimately pointless group ceremonies, led me to decide that I was completely done with the group thing. Communal sessions work beautifully for some people, and that’s fine. But as with everything in medicine, everyone is different, and nothing works for everybody. That’s the nature of human biology.

Getting thrifty with group therapy

Scaling up a group model for therapy isn’t simply a matter of creating another option for people—it’s essential if psychedelics are ever going to be scaled up and delivered to the mainstream in a safe, feasible and affordable manner.

On the crudest level, treating people in groups, rather than one on one, is simply more cost effective, says Rick Doblin, founder and executive director of MAPS, which has been campaigning for scientific exploration and decriminalization of psychedelic therapy since 1986.

Slowly inching towards their goals, MAPS made huge strides in the past five years: In 2017 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted “

breakthrough status” to their MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder model, meaning the federal body recognized that this treatment has a significant advantage over all other currently approved therapies. This year they published the results from their phase 3 trial in the journal

Nature Medicine, with results that were “

even more statistically significant” than they expected, he says.

But one key factor that is lost in all the media hype surrounding psychedelic treatments is how expensive they are to develop and to purchase—proper psilocybin therapy for depression could come with a $20,000 price tag.

“We’ve spent around $75 million to get to this point,” says Doblin. Nobody wants to charge somebody suffering from PTSD $5,000 or even $20,000 for months of therapy (42 hours of therapy in total for preparation and integration, featuring just one dosing of the drug). But in order to recoup those costs, that is simply how the mathematics break down.

“We still think that American insurance companies will pay for that, because PTSD patients are expensive—they have more stress-related illnesses, more emergency room visits. The cost effectiveness of treating them with our model is strong,” says Doblin.

But, he says,

"If people can be treated in groups—even just for the prep and follow up—that could bring the costs down dramatically. My sense is that it is most likely that individual therapy will work better than group therapy—but if group therapy is 80 percent as good as individual therapy, but 25 percent the cost, then that will be much easier to roll out,” he says. Which is why they are already planning a program to treat U.S. war veterans who suffer from PTSD in group therapy with the Portland Veterans Association in Oregon.

UCSF’s Woolley says bringing down costs was also their motivation for treating older men living with HIV/AIDS in San Francisco with psilocybin in groups.

“Think about how much an average therapist gets paid—it’s somewhere between $100 and $250 an hour, so if you need 20 hours of therapy for one patient before you even take the drug, that is a lot of money,” says Woolley.

“We thought we could make this cheaper, more scalable, more available to the masses,” he says, noting in the paper that though psychedelics such as ayahuasca and peyote have traditionally been done in groups, no modern trials had looked at the feasibility of psilocybin-assisted group therapy, and the

“optimal method for delivering psilocybin therapy remains an open question.”

In

a study published in the journal

EClinicalMedicine in 2020, he and his colleagues describe a groundbreaking study dosing 18 gay men over the age of 50 who had contracted HIV before 1996—a time when the diagnosis was still a death sentence, before highly effective anti-retroviral drug combinations were available. All of them, having watched so many friends die a horrible, excruciating death, went on to suffer “survivor’s guilt,” endured decades of shame and stigma, developed severe anxiety waiting for death to come at any moment, and as a result all were burdened with what psychologists call demoralization,

“a form of existential suffering characterized by poor coping and a sense of helplessness, hopelessness, and a loss of meaning and purpose in life,” to quote the paper.

Even if they later received cutting-edge drugs and have lived healthy lives to the present day, the fear, shame, and anxiety never vanished. There are many ugly terminal illnesses in the world—but this one carried a special kind of stigma.

“This wasn’t just any death—this was the loneliest death in the world, and these men felt like death had been hanging over their heads for a long time,” says Woolley.

“Our goal for this study was to help people not feel lonely anymore, and a big part of that was helping them to reconnect with other people. So we thought, why not foster connections with other people in the treatment group?”

Though all men received a dose of psilocybin on their own with a therapist, all their preparatory sessions and all their follow up integration therapy took place together. The 18 men spent a total of 472 hours in face-to-face therapy in groups with a counselor—but if they had done that individually, the study total would have tallied 954 hours, an astronomical cost increase.

Directing attention inward

One inspiration for the group sessions, says Woolley, was learning from researchers at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore that their study subjects who had been dosed with psilocybin to treat their anxiety over having a terminal form of cancer. This study was done in the style made popular in the 1950s (blindfolded and alone with a therapist). But many of the subjects asked to meet the other study volunteers afterwards.

“That never happens with a Prozac study—ever. Even people dosed with oxytocin, the so-called ‘cuddle chemical’ in our other studies, didn’t want to hang out with each other afterwards,” says Woolley.

“But with psychedelics, especially when people are ‘psychedelic naïve,’ they really need to talk about it.”

Psychiatrist Roland Griffiths, who has led studies at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore with psilocybin since 2006, agrees that group experiences have a rich history and may have certain advantages over solitary settings, but he says it’s just logistically and statistically too difficult to dose people in the same room and then pick apart the data. The confounding factors make the statistics a bramble nest.

“We could do group sessions, but we haven’t because the group setting results in complexity in interpretation of results” says Griffiths, noting that sticking to the traditional model works just fine.

“Honestly however, when you ask people to direct their attention inward, they have phenomenal experiences.”

Simplifying the data, reducing the costs, and avoiding messy, traumatizing, or disruptive experiences between subjects led Woolley to opt for dosing HIV sufferers alone—but hosting prep and follow-up therapy in groups.

“I’m glad we did the dosing individually—it would have been too hard to manage all of them at once, each one took our full attention to manage their trips,” he says.

“But for support and integrating, the group was very powerful for that—they did a lot of the work themselves.”

Which makes sense: who else could understand the experience of living with HIV for 30 years other than somebody who has lived with HIV for 30 years? With this line of thinking, researchers around the world are looking at treating anorexia sufferers in groups with psilocybin—a common but bewildering mental health condition for those of us who have never suffered from it.

Even for a condition as common as major depressive disorder—which affects up to 10 percent of the population—sufferers who seek psychedelic therapy may still find (to their surprise) that gathering with other depression sufferers may benefit them more than intense therapy with an experienced therapist.

In 2020, people who had taken part in

Imperial College London’s landmark clinical trial comparing psilocybin to escitalopram, a common antidepressant SSRI (published in the

New England Journal of Medicine this year) were offered integration and follow-up therapy in groups via Zoom rather than in person, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Study volunteer Joe Hyde, a 63-year-old IT professional, hadn’t planned on attending the optional group therapy integration sessions before the pandemic as he lives in Blackpool, England, 200 miles from London. The journey did not appeal—nor did the concept.

“I was very anti group therapy—I just didn’t like the idea of doing this in a group of people I didn’t know,” he says.

“But being in that supportive state allowed me to open up and talk about this and reflect on it in a group, understanding that everyone there had also suffered severe depression. It just seemed to make things fall into place.”

“We were just holding space for each other, and actually listening,” says Alice Thorne, a 32-year-old registered nurse in a pediatric clinic, another subject in the Imperial College study.

“In one-on-one therapy, I always found it difficult to talk and to understand my feelings because I couldn’t find any compassion or acceptance towards myself. But unexpectedly, I’ve loved being part of a therapy group, which is surprising because of my anxiety. I found it challenging at first but over time it has opened me up and brought so much connection and joy.”

Healing conflict survivors

It doesn’t take much to understand the power of talking to other people who were drafted into the Vietnam War, or wasted decades starving themselves, or who lived for 40 years surviving the same HIV/AIDS pandemic that killed all their friends. When you meet somebody who experienced a similar kind of trauma to yourself, it’s “like meeting somebody from your planet.”

This body of work isn’t surprising. But what

is surprising is another project of Roseman’s, who has been studying ayahuasca ceremonies in Israel. There for twenty years, progressive-minded people have brought together Israelis and Palestinians who have been traumatized by the ongoing war (including former soldiers) for psychedelic healing.

At first glance, gathering a bunch of shell-shocked and battle-scarred subjects from opposite sides and giving them all mind-altering drugs looks like naïve insanity. Psychedelics can make one volatile, sensitive, emotional, paranoid, and delusional. A thousand things could go wrong when a dozen traumatized soldiers and civilians from both sides of one of the world’s most concentrated and toxic conflicts are put together and dosed with a soul-unraveling psychedelic that could last up to eight hours.

But this is exactly what people have been organizing in the underground scene in Israel for two decades—primarily with the aim of healing trauma in individuals, ideally with the eventual potential to “contribute to peacebuilding.”

Earlier this year Roseman and colleagues (including Rick Doblin of MAPS) published their

first formal report on this “paradoxical project” for “relational healing” in the journal

Frontiers in Pharmacology, documenting interviews from 31 people (18 Jewish Israelis, 13 Arab Palestinians). Both Israelis and Palestinians described a dissolution of social identities, “shifts of identities,” and how “a strong connection was made to the other culture.”

In their own words:

One Israeli woman: “We really experienced this place in which the connection is not Israel–Palestinian, it is human: the human tribe.”

A Palestinian man: “Everything goes into a state of unity, to the energy that exists between us. We stop viewing each other as Israeli or Palestinian, male or female, Muslim or Christian. It all melts down.”

Another Israeli man: “Suddenly you hear the language you most hated, maybe the only language you really hated and suddenly it is sending you love and light.”

Another Palestinian man: “I had this weird experience of being in the body of an Israeli solider… I could feel him after, that this is painful. This is not an easy life after.”

The testimony I found most eye-opening: An Israeli veteran who had been part of an elite combat unit in his visions revisited a brutal raid and house arrest—except he saw the raid from the Palestinian perspective whose world they destroyed. Seeing it this way, he couldn’t believe what they did, and he said that for the first time, he hated himself deeply for taking part.

“The ayahuasca began to show me this crazy pain and hate and crying for the evil they were experiencing,” the soldier said.

“I felt the heartbreak in the room, and the fear… I can’t believe I am the person standing there.”

This is not something one can envision happening in formal negotiations at Camp David.

“In group circles, suddenly there is resonance between people’s stories when parallel stories meet,” says Roseman.

“Once you deal with trauma in a communal way, you begin to understand the systemic force of trauma. I imagine the future of psychedelic therapy to be local clinics that work with local populations—not [a] distant retreat where you only meet strangers. Having experiences with people around you will strengthen your wellbeing and create community.”

There is a line of thinking that most (if not all) of humanity’s problems on this planet can be traced to trauma—both individual traumas and intergenerational traumas. That’s probably a bit of a stretch. But it’s certainly true that trauma is ubiquitous, and Western approaches have traditionally been terrible at addressing it (stiff upper lip and all that).

However, war is as old as civilization itself, depression affects a tenth of all people at any given time, and other wounds ranging from crappy parents to sexual assault and eating disorders are commonplace. It shouldn’t be too hard to find others who understand your pain and are willing to go deep with you.

A tragic accident

But what do you do if you have a pain that nobody—nobody—could understand?

Whenever I am drawn to feel sorry for myself—for anything—I think of what happened to my old friend Aaron Horn.

In 2006 Aaron was in the garden of his family’s country home, shooting at a target with an air rifle. What he didn’t know was that his mother was in the garden. She was accidentally shot through the neck, and nearly died on the spot, but survived in time for medics to arrive. She lingered in a non-verbal state for eight years, eventually dying from cancer in 2014. A cruel twist: Aaron’s father is the Grammy Award-winning producer

Trevor Horn, so the news splashed over the papers. Aaron was only 22 when “the accident,” as he calls it, happened.

By any yardstick, he coped astonishingly well. He kept working, he had a son, he kept making music, and

he had a number one single. By any measure, that’s pretty good.

But still, something was missing—how could there not be? There were some dark times and bad trips—how could there not be?

Various things helped, he says, such as music, psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, friends,

even CBD. But nothing really transformed him like a group ayahuasca session. “It’s like he’s back in the room,” as his ex-partner put it.

Which I found astonishing. How could spending eight hours with people whose problems are pathetically miniscule compared to yours possibly help? If I had to deal with the tragic death of my mother while hearing some kid from Manhattan whine about their marketing career, I wouldn’t feel healed—I’d feel enraged.

When I last spoke with him, it was the first time Aaron has spoken publicly about what actually happened in that trip. What he said was remarkable.

“In the actual accident, I lost my shit—my body went hot and cold, I was completely in disarray, I lost consciousness while being conscious. People told me I ran around like a headless chicken for about 45 seconds,” he says.

“In the ceremony, there was symbiosis with that event itself—hot and cold, disarray. I was able to access the spiral of time… and go back to see myself in that trauma. I just gave myself a hug… and I was just there for myself. It was deep cognitive reprogramming.”

Psychotherapists, psychiatrists, healers, and hippies often speak of the concept of “self compassion.” But I’ve never heard anyone articulate what that actually means in a clearer way than Aaron.

“The person who shows up for you is you,” he says.

Which makes complete sense to me: Safer to feel you can rely on yourself than anyone else.

Yet still, for Aaron, the group was crucial. After all, it is said that

“trauma is pain that goes unseen.”

“There is something to do with being watched by other people. Once there is a certain number of people around you, nothing is missed,” he says.

“We are meant to get support for trauma in groups. Humans are not meant to be on the lookout constantly for signs of danger, which is the very definition of PTSD. It’s not easy being watched, but part of getting over trauma is grieving—and part of grieving is having other people see it… and be there for it.”