Using psychedelics to treat PTSD in couples*

by Dan Bernitt | Psychedelic Support | Oct 1 2019

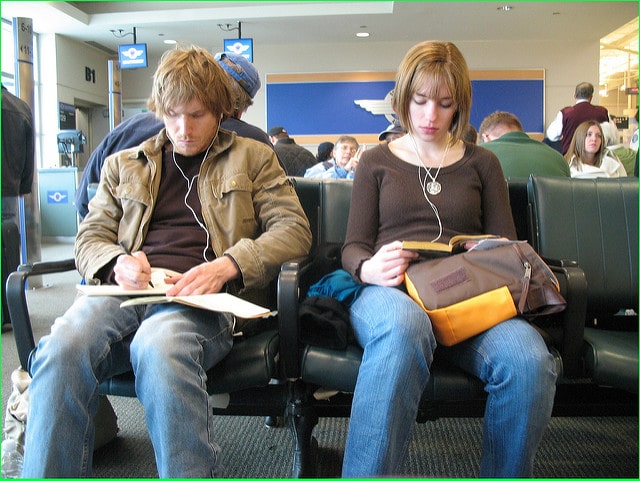

Psychedelic therapy can benefit individuals with PTSD, but can it also help couples better deal with this condition? Randy Lail enters MDMA-assisted psychotherapy treatment with his partner and participates in an MDMA study focused on couples.

For more than a decade, Randy Lail cycled in and out of depression and anger issues.

“I thought I was as normal as anybody else,” he recalled. “But it got worse as I got older, and I didn’t really understand what was happening.”

The death of his father in 2000 exacerbated his emotional struggles. His work and family relationships began to spiral downward. In 2004, after a failed suicide attempt, he began to get his life back on track. He was able to focus back on work, involve himself in a church, and grow strong relationships with his wife and children.

“The memories started pouring out, like somebody turned on a spigot.”

More trouble was around the corner. In 2008, with the financial and real estate markets collapsing, he ended up without a job. His emotional struggle took a new turn:

“One day, all of a sudden, I got this flashback of being abused by my dad. The memories started pouring out, like somebody turned on a spigot.”

He turned to his faith for help. He and his pastor prayed about the situation.

“But it didn’t get any better. It was a faith crisis for me at that point. I walked away from God, church and everything, as much as I could. I told God if he wanted me He knew where I lived.”

When the memories were too much, he tried to suppress them. It worked for a while, and he was able to find a job and reestablish himself to a degree.

“Trying to keep a lid on that stuff is like trying to keep a weight on top of a pressure cooker. I just kept popping,” Lail said. He tried speaking with pastors again, but he realized he needed help they weren’t able to offer.

Looking through a list of psychologists near him in Charleston, South Carolina, he emailed Dr. Deborah Marcet, the first psychologist on the list who also had a website.

“As soon as I hit send, she called me in less than five minutes,” he said.

“I must have sounded pretty desperate.” Within days, they began working together, and she diagnosed him with post-traumatic stress disorder.

They began working through his traumatic memories using a few different therapeutic modalities, including talk and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy. As they worked through more complex and challenging memories, Lail would need a break to let settle what was being unearthed.

“We were uprooting so many memories, but some of the memories made sense while others didn’t. They were twisted up. They didn’t seem to follow any linear timeline; they were just coming out randomly.”

That’s when he hit a wall. He would approach painful memories around his childhood abuse, and he’d begin to shake uncontrollably, his whole body shuddering. He couldn’t continue. Months would go by before he could handle another appointment.

The morning before one of his appointments, his wife Cynthia read a newspaper article about a firefighter with PTSD. The firefighter had been a first responder to a furniture store fire. Nine of his fellow firefighters died in the blaze, and years later he had been on the verge of taking his own life until he was able to participate in a study of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for treating PTSD.

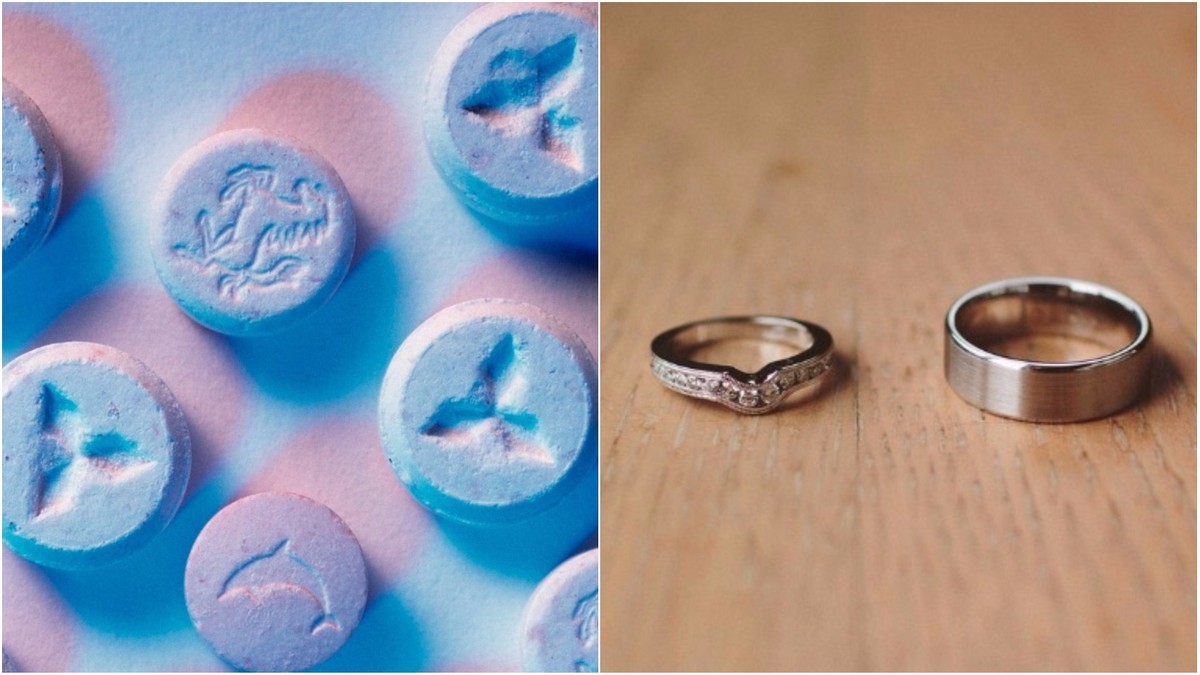

“When Cynthia read it to me, I looked at her and said, ‘I’m not taking Ecstasy,’ ” Lail said.

“I sat there thinking, ‘Ecstasy? That stuff’s a fricking rave drug. What the heck?’”

Despite his incredulous response, he brought up the article with Dr. Marcet later that day.

Dr. Marcet said,

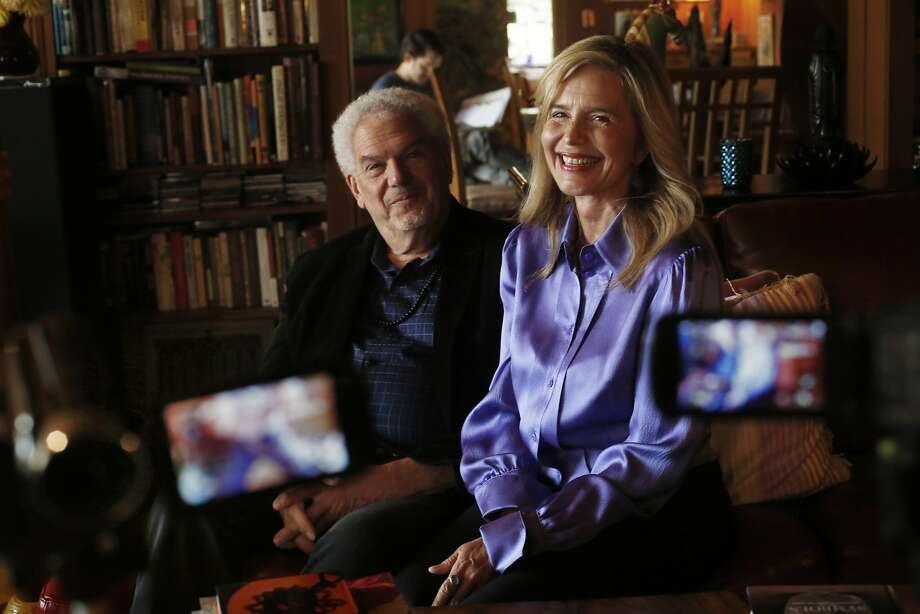

“You’ve got a big block here. It’s obvious you have a very painful memory.” She suggested that MDMA-assisted psychotherapy might help him. To his surprise, Dr. Marcet knew the therapists involved in the study in which the firefighter participated, Dr. Michael and Annie Mithoefer.

“She called them while we were sitting there in therapy,” Lail recalled.

“She picks up the phone and calls Michael, and he answers. Isn’t that crazy?” Mithoefer had been wrapping up a study trial, and he mentioned to Marcet that another study was accepting applications for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for couples struggling with PTSD. Both partners would participate and take the medicine.

The process for being approved for the study was deeply involved: health checks, physicals, blood work. The mounting risk of being denied sent Lail into a tailspin.

“I was borderline functional at that time,” he said, nearly being denied access twice.

“I was getting myself prepared to be turned down. It was scary because when you’re dealing with PTSD, it’s all about being in control. You have to control your environment, everything. Control is the only way you can keep your sanity, and it was wearing me down.”

During the waiting period, Lail would pray before bed.

“I’d say to God, ‘Thanks for getting me through the day. But I don’t know if I can do much more. If it’s not too much trouble, I’d be OK if you’d take me home now.’”

Soon after, they were one of six couples accepted into the study.

Dissolving divisions

In her training as a clinical psychologist, Dr. Anne Wagner enjoyed the framework of working with couples.

“It can be really different than working with individuals, because you’re entering a system with them: this dance and dynamic that they’re living and interacting with. The approach we use is that the relationship is the client—it’s not one person or the other—and we do what’s in the best health and favor for the relationship, whether it’s for the relationship to continue, dissolve, or otherwise evolve,” Wagner said.

“Oftentimes people have lost a fair bit of hope. They get to experience a deep level of healing they didn’t think was possible.”

In the study’s protocol, it’s key that both partners participate together in all parts, from initial consultations and preparatory sessions to the therapy and medicine sessions to the integration process. By participating together, they develop a shared set of tools and language for how they’ll engage in the MDMA experience. This design limits the risk of a rift emerging between a partner who had a profound experience and another who was merely a spectator of change.

Where Wagner’s focus is on the relationship as the client, Dr. Will Van Derveer, a Boulder, Colorado-based psychiatrist, has focused on the habits and histories each person brings into the relationship. He looks at healing each partner’s attachment patterning.

“A lot of those challenges that people face in partnership are the challenges that are being repeated from the early attachment environment that we had with our caregivers when we were infants,” Van Derveer said.

A ketamine experience, Van Derveer explains,

“takes down the laws of the self. Your sense of who you are is very extended, and it’s kind of blended with your environment, with the universe, and with the past, present, and future. The softening or disintegration of this really powerful me, me, me, me perspective is helpful for people.”

His own ketamine experience helped him form a protocol for using it with couples. He rested his head in the lap of the facilitator while he journeyed through the medicine.

“As I started to come out of the ketamine dissociation experience, that one thing that I was aware of was the sound of her breath in my ear. It felt like I was an infant being held by my mother in that moment,” he said. Ketamine broke down many barriers and experiencing this answered deep existential questions:

“Am I safe? Am I going to be taken care of? Is there someone here for me? What’s going to happen if I feel dysregulated, or if I’m hungry, or if I’m tired, or if I’m scared, or if I’m thirsty? Was there somebody going to take care of me?”

In a protocol designed by Van Derveer, each partner will alternate turns experiencing ketamine, resting their head in their partner’s lap. As the medicine wears off, each person wakes up to the face of their partner, the one with who they can create answers to these questions. Van Derveer believes in the ripple effect of repairing attachment styles;

"encouraging interdependency, trust, and security in a relationship automatically translates into more capacity to trust the intentions of other people out in the world, too.”

Dr. Wagner sees the same impact in her work with couples using MDMA.

“People communicate to us that they’re able to see things in a new light and feel like they get their lives and relationships back,” she said.

“Oftentimes people have lost a fair bit of hope. They get to experience a deep level of healing they didn’t think was possible.”

This change is not without significant work on the part of the patient. Wagner says it’s important for the therapist to know when to get out of the way:

“That’s a really, really, really important piece we forget a lot. Societally, we’re taught to either stop or soothe emotion when it comes up. In session, you want them to experience the emotions.”

In his preparatory session, Randy Lail asked what he’s supposed to do during the medicine work. Dr. Michael Mithoefer, who started as an emergency room doctor, likened the healing of physical trauma to emotional trauma.

“The doctors are there to sew you up, close up the wound,” Lail recalled hearing.

“But your body does the healing. It’s very similar for your psyche. Your brain knows what it needs to do to heal. You just got to get out of its way.”

Lail’s own apprehensions grew as the dates of the medicine sessions came closer. He reflected on their relationship and life together: they’d known each other since eighth grade, attended church together, began dating in 1979, married since 1982.

“I wasn’t sure who I was going to be when this was over,” he said. As part of the study, they were asked separately what their biggest fear was. They both had the same concern: Once we’re through this, will we still love each other?

Finding wholeness

In the medicine session, both Randy and Cynthia Lail took the MDMA, donned eyeshades, and laid back to relax. What follows is Randy’s experience in his own words:

Before MDMA, I was re-experiencing the trauma. After MDMA, I’m just remembering. Big difference!

During the first session, as soon as I went in and went under the influence of the drug and I laid back and let my head clear, I went straight to the very beginning of my abuse. That whole day was spent going from the beginning to the end, and going through those memories.

The abuse was really bad between the ages of three to 14, however the last year was the worst. I had gotten introduced into a pedophile ring of other men and women. And there were some things that were done to me in that were extremely abusive… I never could really get past those memories before. The fear and the hurt and all the emotions were alive. It was like when I would get close to those memories, it was like living it again.

I had this memory of being at a camp, like a boys camp kind of thing. On its face, the camp didn’t look any different than any other summer camp, where kids would go to and spend a number of weeks at. There were cabins and a lake and places to play ball… all that kind of stuff.

But there was this one memory that would jam me up. It had to do with a gazebo and a cabin, and there was this particular lady that was involved, too. I would basically say she was my groomer. Her name was Sue. As we moved from that gazebo toward this cabin is where all this pain and anguish and hurt and fear would stop me from remembering more… It was like all these feelings were all wrapped up together.

It was just so overwhelming that the memory wouldn’t go past approaching that cabin.

During my therapy sessions with Dr. Marcet, I would just sit there and shake uncontrollably. I just couldn’t stop. I mean just shuddering type feeling, just really hard to describe. I would just throw up my hands and say,

“No more. I’m done. Stop, stop, stop.”

I didn’t actually breach this memory during the MDMA session. It happened several months after the MDMA was over.

After I processed those two MDMA sessions, my PTSD was gone. I’m seeing another therapist now, and we’ve worked through a lot of the remaining memories. Post-MDMA, I’m remembering them, not reliving them. I’m still having emotional feelings around them , but it’s not the same anymore. It’s like this uncovering of a memory, not uncovering an experience.

Before MDMA, I was re-experiencing the trauma. After MDMA, I’m just remembering. Big difference!

The things I remembered prior to the MDMA were fragments and pieces out of order. What I’ve remembered post-MDMA is my memories unfolded in order. I was able to go back into the same place I described earlier, that cabin scene and all that. Each session I get a little bit more, and a little bit more, and a little bit more, and it’s all unfolding in order. I couldn’t do that before MDMA.

It almost was like my brain was rebooting or defragging, putting the memories where they are supposed to go. My brain has the ability to heal itself. I just needed to get over the fear part and let the memory process and finish. I never really understood that PTSD is a trapped memory that doesn’t get processed into long-term memory. When we go to bed at night, our brain converts short-term memory into long-term memory. What happens to people with PTSD is a trauma stays current causing them to relive the trauma over and over again. By not converting your brain can’t finish the process. So, you stay stuck. And it makes good sense to me now because that’s how I felt—stuck.

In addition to helping correctly process memories, the MDMA experience allows the psyche to generate experiences through a symbolic dreamlike language—deeply felt and understood, unique to each person. Randy’s faith came alive to him in each session.

What I didn’t expect was to see next to me, sitting to my left, was Christ.

I know it was Christ. Some people will say,

“It’s your spirit guide.” Whatever you want to call it.

But I know who it was, and He went through the whole thing with me.

When I felt like I couldn’t look at something, He was right there to help me. And He said,

“I’m here with you, it’s okay.”

He even showed me in memories where I was a kid that… I always wanted to know why did this happen? Why, why, why? And I came out of that second session, and I feel like I got my why answered. Not that anything that made it right or wrong or whatever you want to call it. I felt like I was at peace finally with all of it. And that’s where my healing began.

There was this one image where I was standing with Christ, and He showed me my family. I saw my mom. I saw my dad. My brother who just passed away not too long ago. And right next to me there was a small kid. I picked him up, and it was me—little me. Not soon after that we merged together, and it was said to me:

“No longer will you two be separated, apart. Now you’re healed.”

Throughout Randy’s deep work with the medicine, Cynthia would relax, but if she heard her husband sit up or shuffle in his spot, she’d always pick up her blindfold and look at him, attentive. When she shared her experience with Randy later, she said,

“I was just laying back and praying.”

A new genesis

“This kind of relational healing work is foundational to dealing with all the problems that we’re seeing all over the world—conflicts, misunderstandings, assumptions that people make about intentions, negative intentions people have, and so forth.”

Randy Lail is quick to note that the MDMA experience was not a cure, but a catalyst. Where previous therapeutic work had felt like one step forward and ten steps back, he and Cynthia’s life is now able to move forward. He said,

“It’s the beginning of a new life. I’ve got a chance now to heal and grow through this. It was a renewing of our relationship because it brought us to a level of closeness we haven’t had in a long time.” While routines solidified after nearly four decades of marriage, the experience has also given them an opportunity to see their habits and themselves from a different perspective and explore and deepen their intimacy.

Randy has advanced within his company to a regional vice president position.

“I’ve always been the kind of person who’s a doer. I get focused on where I’m at today, and this is what I need to be doing. I feel like, I’ve gotten through this, and I’m over it now. What’s next for me in this? How can I make a difference for people like myself who haven’t gotten this far?” He’s begun writing about his experience, too, which has been therapeutic in helping him finalize the past.

As Dr. Van Derveer notes,

“This kind of relational healing work is foundational to dealing with all the problems that we’re seeing all over the world—conflicts, misunderstandings, assumptions that people make about intentions, negative intentions people have, and so forth.”

As an individual heals, so do their relationships and families. As families heal, communities heal, then nations. Wholeness begets wholeness. After divisions dissolve, there is only one—may it never be outside of us; let it be what we create together.

MDMA-assisted psychotherapy can benefit not only patients suffering from PTSD but also those they love. Experiences from the first MDMA study for couples.

psychedelic.support