mr peabody

Bluelight Crew

- Joined

- Aug 31, 2016

- Messages

- 5,714

Cambridge

Ketamine, the new suicide prevention weapon

by Mark Shenefelt | Feb 24, 2019

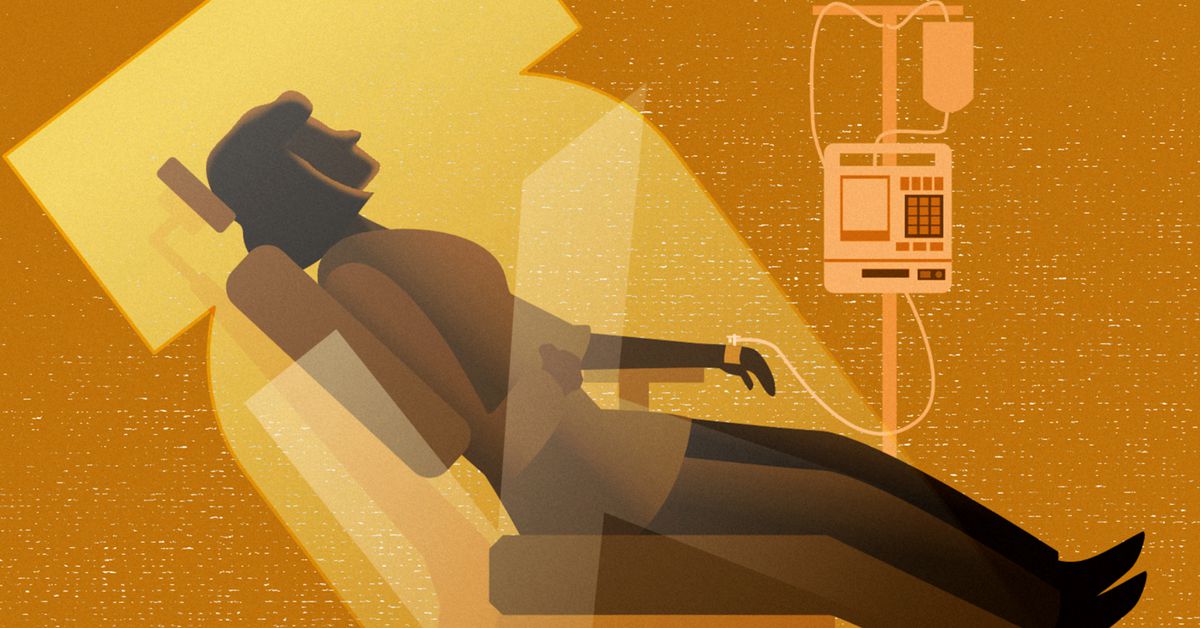

Ketamine, with a long record as both a dependable surgery anesthetic and a notorious club and date-rape drug, has gained new life in northern Utah as a weapon against severe depression and thoughts of suicide.

"I am so blown away by how it has changed me," said Laura Warburton, who runs a local teen suicide prevention nonprofit and learned about ketamine's latest emergence as part of her work.

Practitioners and patients describe the new intravenous ketamine treatments as a last-resort stab against cases of depression so deep that other forms of therapy have not worked.

Ketamine's new path has grown rapidly in the past several years with clinical research that identified its usefulness against depression, suicidal thoughts, anxiety, post traumatic stress disorder and chronic pain, according to National Institutes of Mental Health documents.

Stan Summers, a Box Elder County commissioner, is excited by the prospect that ketamine may help his son, Talan. The 27-year-old has an incurable and excruciatingly painful disease that attacks his internal tissues. He's now on palliative care.

"He's been on narcotics for years," Stan Summers said. "We're very interested in ketamine as another good alternative, like medical marijuana."

Warburton and other local patients have been receiving periodic intravenous infusions of ketamine, including those administered at the Therapy Reset clinic in Washington Terrace.

The intravenous treatments of ketamine being offered locally are off-label applications of the drug, meaning the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved it for use against depression, and therefore it is not covered by insurance.

Meantime, an FDA advisory panel Feb. 12 recommended approval of a derivative medication, called esketamine, that would be administered by nasal spray as a treatment for therapy-resistant depression.

"At Therapy Reset, a six-infusion course of treatment runs about $2,000," says co-owner Chris Weston. "Similar treatments in the Salt Lake City area and in other states may cost as much as $1,500 per dose," he said.

After the initial infusion, most people no longer have suicidal thoughts, Weston said. Over the following treatment course, further improvement in depression is seen by most, he said.

"Many people we see are in a state of mind where they're ready to end life or just have severe depression," Weston said. "Weeks later they are a bright, vibrant, functioning person again."

Warburton said she decided to try ketamine herself after a friend's daughter attempted suicide and then underwent ketamine treatment.

"This child has completely changed," Warburton said.

Her own daughter, Hannah, was lost to suicide, which is what led her to establish her nonprofit, Live Hannah's Hope.

Warburton also continued to struggle with her past. She said she was abused as a child and was abandoned by her father.

After seeing others helped by ketamine infusions, Warburton said she decided, "Before I can fix anybody else, I have to fix myself first."

She said the infusions have greatly reduced her depression and anxiety.

BOOSTER TREATMENTS, OTHER THERAPY

Practitioners caution that other care from therapists and primary care physicians also may need to be continued and that booster treatments of ketamine are needed by some after the initial course.

Nurse anesthetist Krystal Tipping said she had been administering ketamine for anesthesia for 10 years before she began giving infusions for Therapy Reset.

"Most patients have tried traditional anti-depressants, mental health counseling and other treatments, with little success," she said.

"They are at the end of their rope when they come to us," Tipping said.

"Most patients receiving the infusions have been suicidal," she said, "including teenagers whose suffering is so severe that they have been institutionalized."

She has treated some teenagers who are plagued by "suicidal thoughts they can't get out of their head."

"But after the first ketamine treatment," she said, "that's one of the most amazing things, that's one of the first things they say is gone."

"The next largest groups the clinic sees are first-responders - nurses, police officers, EMTs, and veterans who have suffered from "very significant PTSD," she said.

KETAMINE RESEARCH

Some small clinical studies have evaluated intravenous ketamine therapy.

A 2017 study published by the National Institute of Mental Health said an initial treatment "brings about rapid and marked attenuation of depressive symptoms; the benefits are observed within hours of administration, peak after about a day, and are lost 3-12 days later."

Benefits can be maintained for weeks to months by periodic additional treatments, the study said.

Potential side effects include temporarily elevated blood pressure and heart rate and mild dissociative thoughts, the study said.

A 2016 Mayo Clinic study concluded "the anti-depressive effect of ketamine persisted for several weeks after the end" of treatments administered over several weeks.

MISCONCEPTIONS

The National Institute of Drug Abuse said ketamine, which was created in the 1960s and has been used ever since as an effective surgical anesthetic, gained a reputation as a club drug because it can distort perceptions and produce feelings of detachment.

It also has been used as a date-rape drug, administered by a predator to incapacitate a victim.

Ketamine has been diverted for illegal street use mostly through thefts from veterinary clinics, where it's also used as an anesthetic, or from supplies smuggled in from Mexico, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

"I think people have a misconception or fear about mental illness and a misconception about ketamine as well," Tipping said. "They just think ketamine is being abused, it's a club drug, it is unsafe, but that just isn't true. It's very safe to give, especially to the right patient."

She said she's administered ketamine in a surgical setting to many people, from newborns to 100-year-olds.

Warburton said that had intravenous ketamine been available for her daughter Hannah, "I would have mortgaged my house."

"People have no idea how expensive funerals are, on so many levels," she said.

https://www.standard.net/news/educa...cle_1ee6926a-44d0-5c24-a2a5-cb3c60f91066.html

Last edited: