mr peabody

Bluelight Crew

Psychedelics and Perception*

Reviewing early research (1895-1975) on changes in visual perception

by Joshua Falcon, MA | Psychedelic Science Review | 6 Oct 2021

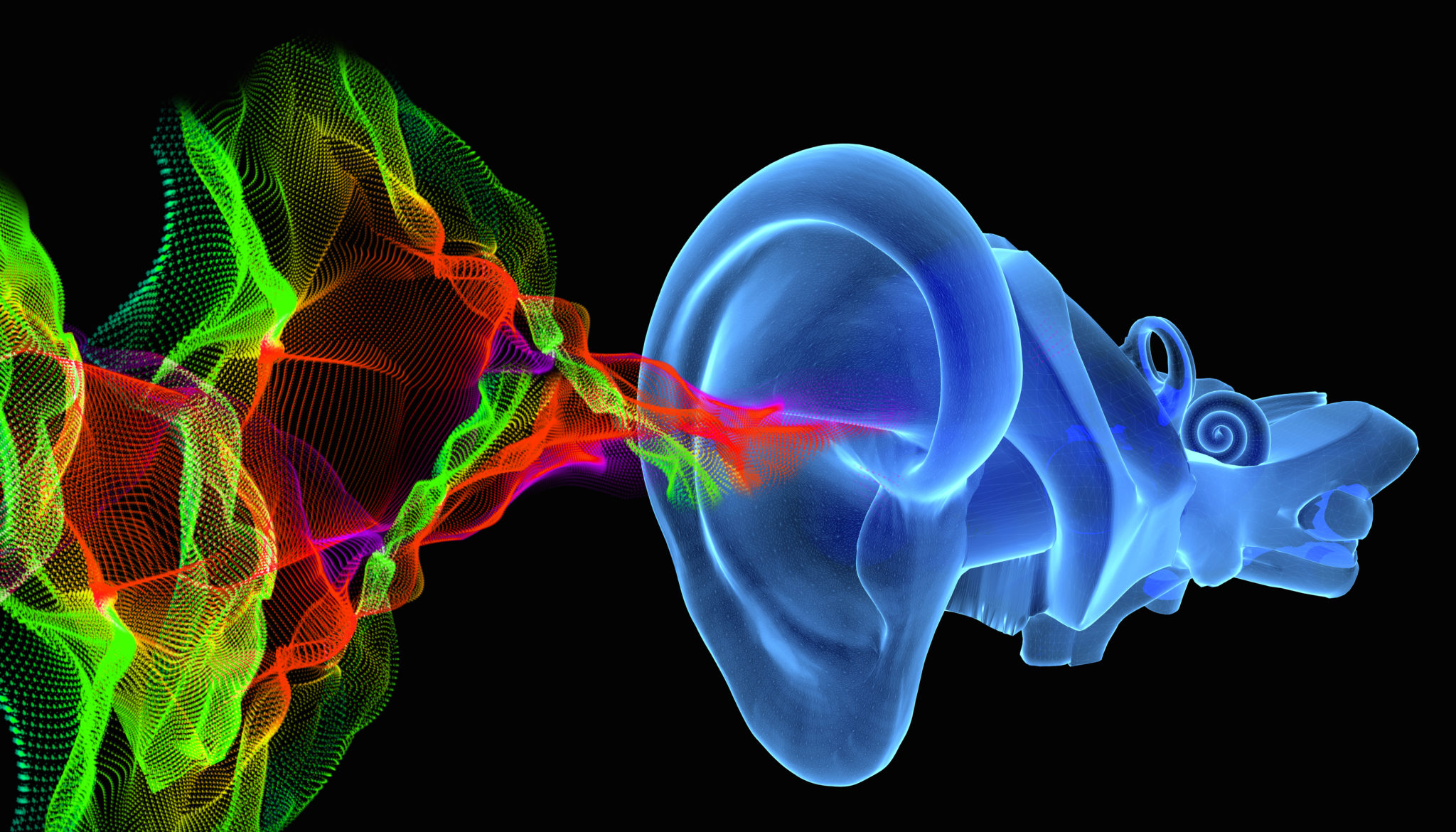

Psychedelic drugs have long been associated with temporary alterations in perception. These changes include, but are not limited to, auditory, visual, and sensory distortions or hallucinations, alterations in body image, and modifications in one’s sense of time. Although early studies are often overlooked due to recent advances in scientific methods and technologies, valuable research was conducted on the physiological changes that psychedelics produce at the visual, auditory, and sensory levels and how these are associated with phenomenological changes in perception.

In a recent review article, Aday et al. provide a novel synthesis of scientific literature drawn from the first era (1895-1975) of psychedelic research. While the early research was predominantly concerned with changes in visual perception, there was also research conducted on auditory processing, changes in body schema and tactile processing, and alterations in the perception of time. The following article summarizes Aday et. al.’s review of psychedelics’ effects on visual perception by drawing out some of its key findings and areas where further research is needed.

Physiological changes in vision

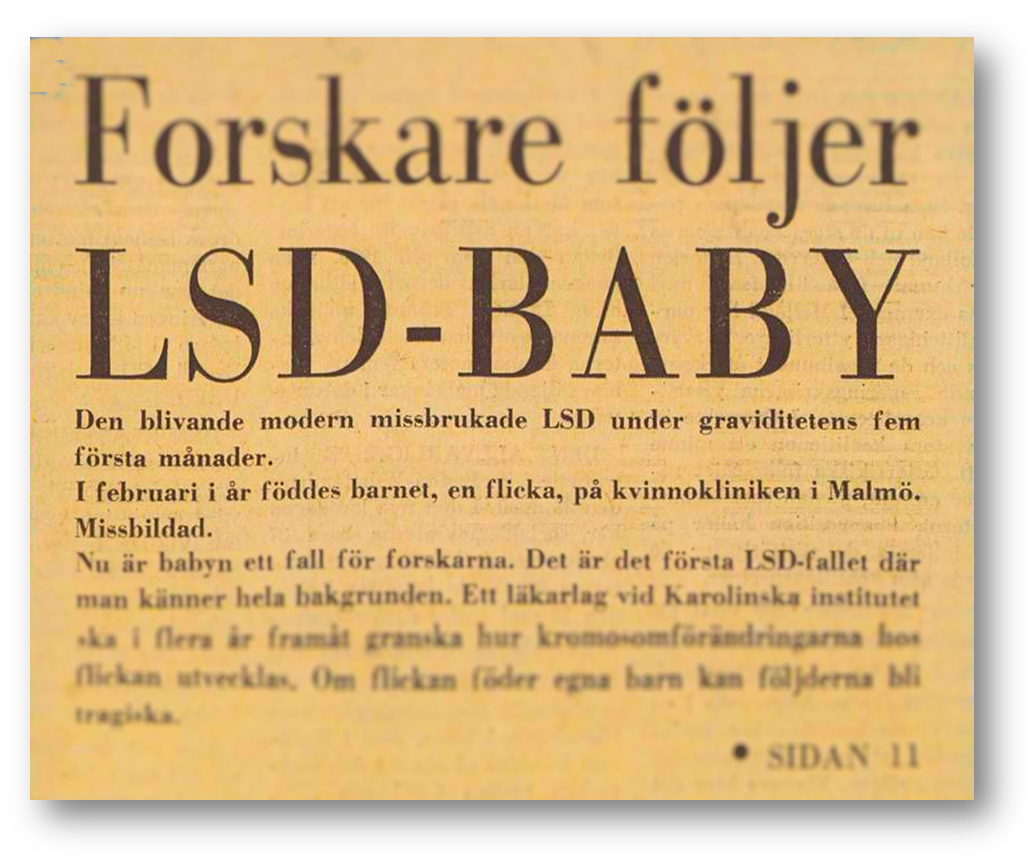

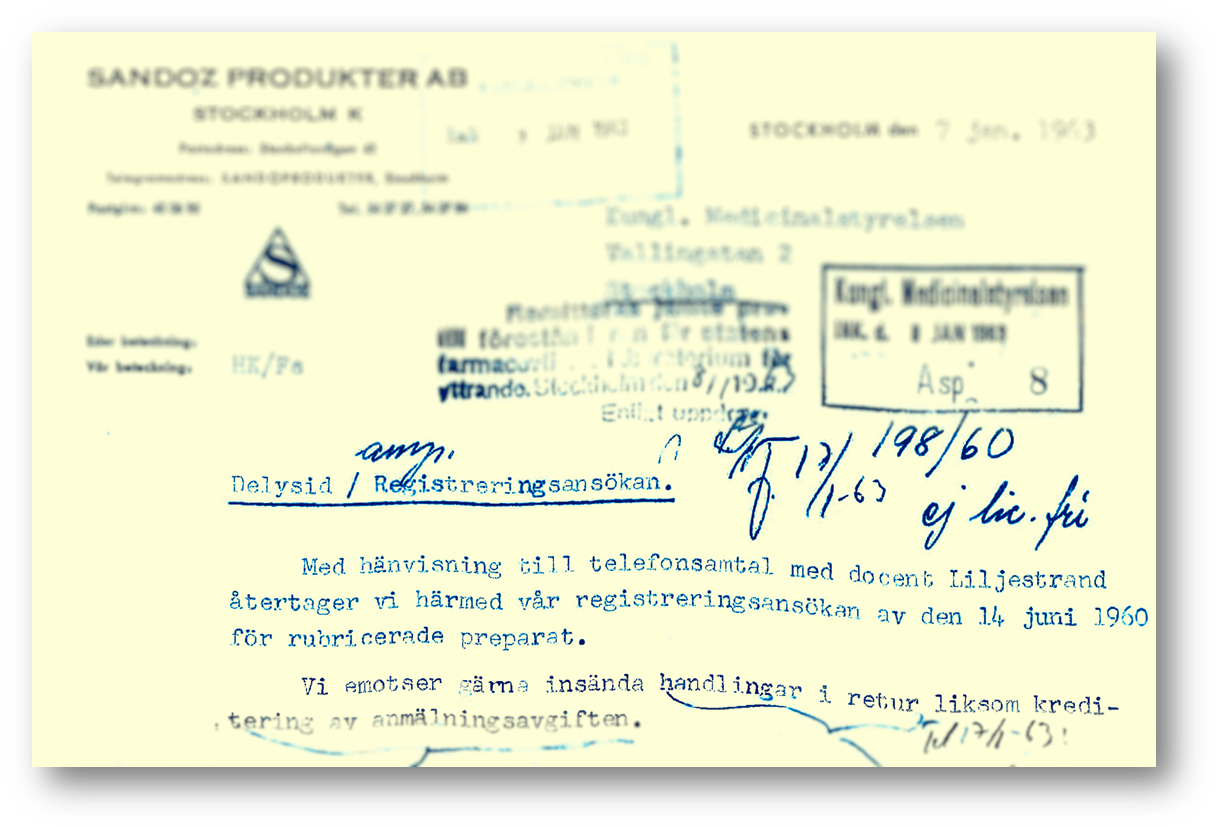

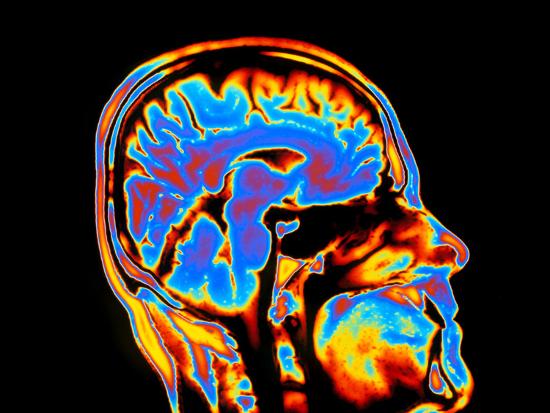

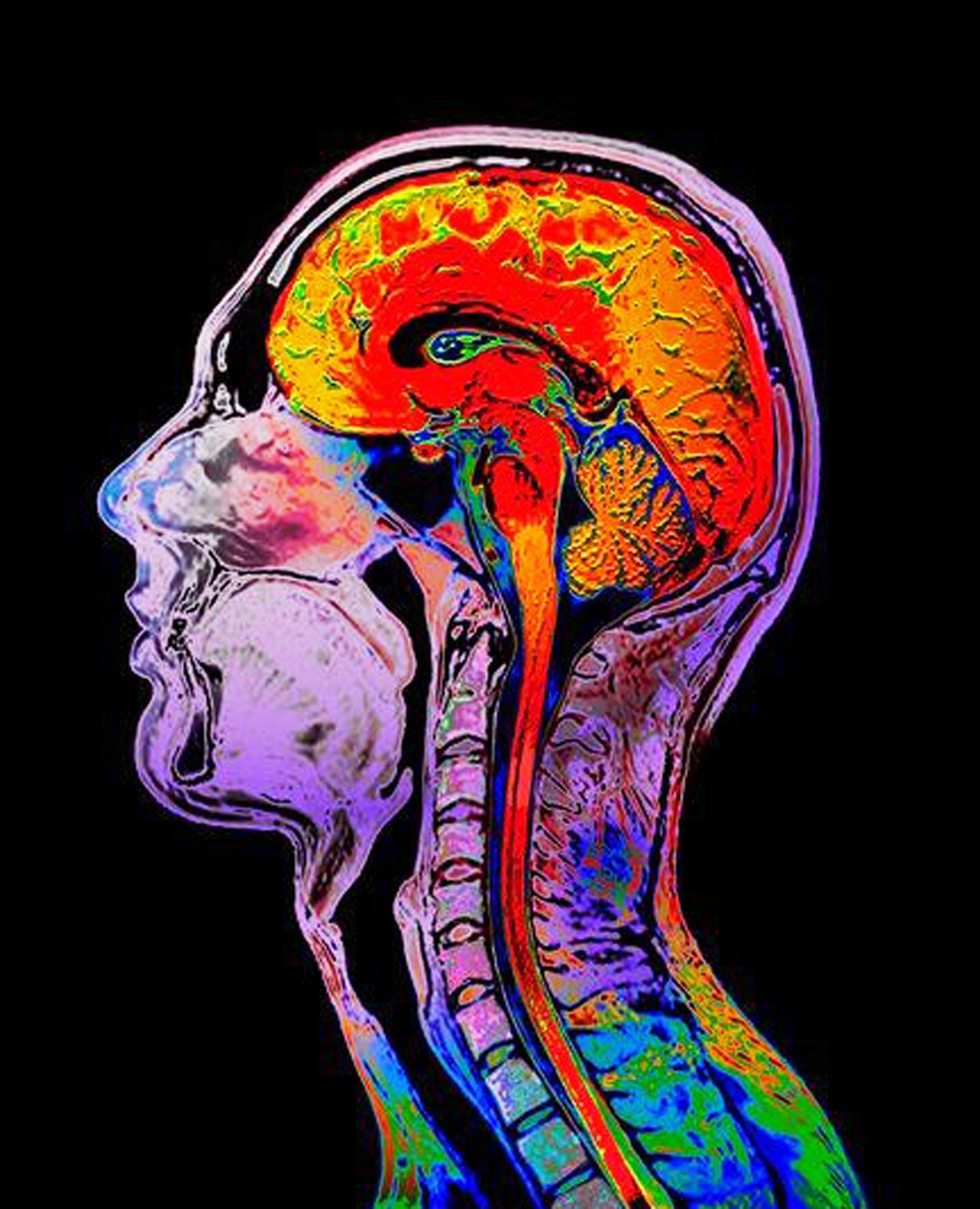

Upon reviewing the first era of studies, Aday et al. suggest that there remains a longstanding debate that has heretofore fallen by the wayside over whether psychedelic-induced changes in visual perception stem from alterations in the brain versus the peripheral eye. On the one hand, early animal studies from the 1950s and 1960s exhibited elevated levels of LSD found in the iris of monkeys. Additional research from this period found that LSD produced spontaneous firing in the sclera, visual cortices, and optic nerves of cats, leading some to hypothesize that changes in visual perception may stem from physiological changes in the retina and peripheral eye.

On the other hand, research conducted between the 1950s and 1970s suggests that changes in visual perception may instead stem from the brain insofar as studies on both blind individuals and in animal models exhibit neurological changes at the cortical and subcortical levels of the visual system.

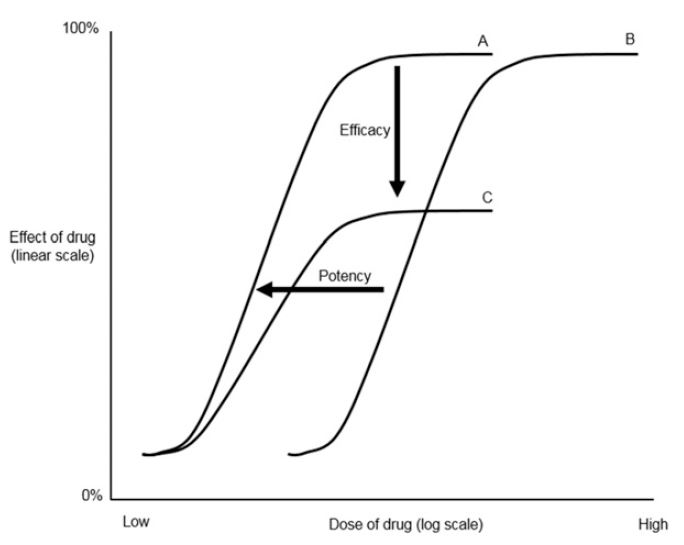

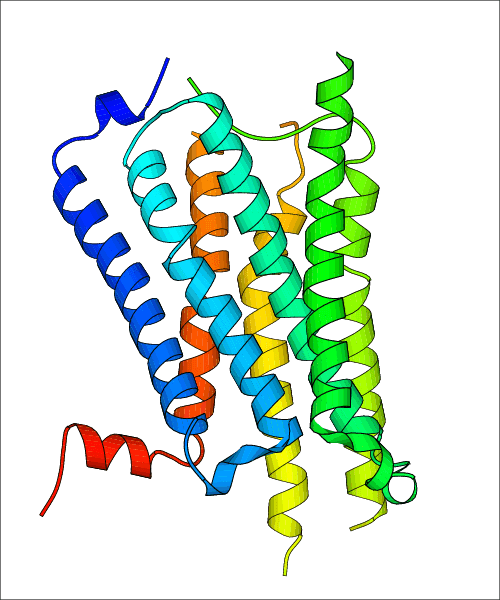

Despite this era of research being technologically limited to electroencephalography (EEG), notable findings show that changes in cortical activity are more pronounced than changes in the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) under the effects of psychedelics. This hypothesis is not only thought to be consistent with contemporary claims which posit that the effects of psychedelics are primarily exerted through the 5-HT2A receptors, but it also lends credence to the idea that modifications in brain activity are more pertinent, robust, and dynamic than those located in the peripheral eye and the retina. Given certain discrepancies in the data, however, further research is needed on the brain versus peripheral eye debate as well as in other areas where discrepancies are found such as changes in alpha activity.

Changes in simple visual processing

The visual changes provoked by psychedelics are thought to stem from changes in elementary visual imagery (EVI), or changes in motion, form, and depth. In studies conducted during the 1950s with participants who had their eyes open, it was found that LSD changed perception in apparent horizon and apparent verticality, as well as elevations in low-level visual thresholds, while psilocybin contracted the perception of nearby visual space. These findings suggest that transformations in visual perception may ultimately be influenced by alterations in low-level visual processing; a point that appears to be at odds with recent studies, signaling the need for further research.

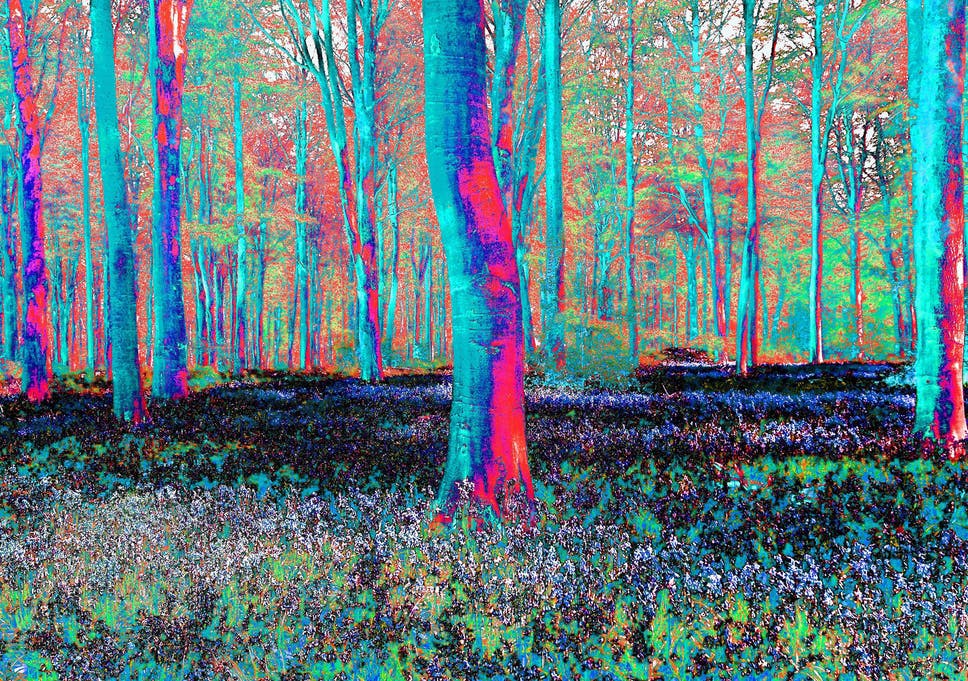

In studies from the 1940s where participants had their eyes closed, reports of geometric and kaleidoscopic patterns appearing in one’s visual field were reported and grouped together by researchers according to their phenomenological descriptions. These groupings included dynamic patterns such as tunnels, cobwebs, spiral designs, and cones to name a few.

Alterations in the perception of color can also be found in several of the first era of studies based on reports of increased color saturation or vividness. One study from the 1960s, in particular, found that LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline equally impaired color discrimination performance and suggested that each drug may affect the perception of different hues.

Complex visual imagery

Apart from changes in low-level visual perception, early studies also show that psychedelics tend to provoke intricate and evolving visionary experiences. Today’s researchers describe these changes in perception in terms of complex visual imagery (CVI), and individuals often describe these experiences as being dreamlike or vivid. Both anecdotal reports and self-experimental studies published during the first half of the twentieth century have long attested to the ability of psychedelics to produce these enduring, changing, and internal visions; however, these experiences prove difficult to quantify. Nevertheless, psychedelic experience reports are rife with references to internally experienced dynamic visions dating back to the early stages of psychedelic science. Although the nature of CVI has proved elusive, it is suggested that researchers should be on the lookout for cognitive factors that may be related to CVI, such as increases in creativity and metaphoric thinking.

The first era of research (1895-1975) into the effects of psychedelics on perception contains valuable findings that can be useful to researchers today. These include debates on how psychedelics produce physiological changes in the brain, the peripheral eye, and the retina to provoke changes in visual perception, as well as how alpha activity is affected by psychedelics.

Researchers during the mid-twentieth century found that psychedelics produced changes in low-level visual perception, increased vividness in color perception, as well alterations in the perception of certain hues. The significant visionary effects that are often produced by psychedelics were also investigated during the first era but proved difficult to quantify, signaling the need for contemporary research into the cognitive factors associated with the more profound and complex changes in visual perception.

Stay tuned for further articles in this series discussing changes in auditory and tactile processing, body schema, and time perception brought on by psychedelics.

The First Era of Research

Psychedelic drugs have historically been recognized for their ability to produce changes in various aspects of perception. Upon examining early research conducted on psychedelics and changes in perception, Aday et al.’s recent review article synthesizes evidence drawn from the first era (1895-1975) of psychedelic research.

This article, Part 2, surveys a second portion of their review by examining the early evidence on psychedelics and changes in auditory perception. It highlights key findings drawn from the first era of research on psychedelics and changes in non-visual perception, while it also brings this evidence into conversation with contemporary studies where either resonances or discrepancies in the data exist.

Changes in auditory processing

Apart from investigating how psychedelics produce changes in the sphere of visual perception, researchers from the first era of psychedelic science also examined alterations in auditory perception. Behavioral studies conducted during the 1960s and 1970s, for example, found that LSD and other psychedelics reduced auditory sensitivity and led to increases in stimulus generalization. In contrast, other research conducted during this time period using animal models claimed that, in general, psychedelics produced fewer responses and reaction times overall, while they also appeared to have no effect on stimulus generalization. These observations of delayed reactions to auditory stimuli were also frequently reported across studies on psychedelics from the 1950s to the 1970s.

Around the same time, other experiments directed at studying the neural correlates of auditory alterations showed that mescaline, in a dose-dependent manner, increased the amplitude, latency, and peak area of the N1 and P1 auditory evoked potential (AEP) components in cats. Another notable study from 1971 compared how DMT and LSD differentially affect AEPs, suggesting that while LSD appeared to have no effect, peak DMT sessions showed a disappearance of AEP’s that tended to gradually resurface as the effects of DMT diminished. Aday et al. interpret the latter findings as being consistent with more recent studies on DMT, where individuals commonly report increased dissociation from their immediate surroundings.

Auditory hallucinations are another area of research investigated during the first era of psychedelic science; whereas some insisted on auditory hallucinations being common occurrences during psychedelic experiences, others considered them to be rare. Of the few early studies which quantitatively investigated the occurrence of auditory hallucinations, their frequency was considered to be uncommon. Instead of interpreting these changes in auditory perception as auditory hallucinations, some researchers during the 1930s and 1950s respectively suggested that these were perceptual distortions of objective stimuli. Aday et al. believe these results to resonate with contemporary studies wherein alterations in auditory perception have been examined.

Lastly, in undertaking investigations on the effects of music on psychedelic experiences, the first era of research produced several insights that would later be confirmed in more recent studies. In 1970, for instance, researchers suggested that music eased patients’ ability to “let go” during psychedelic therapy sessions, allowed patients to more fully explore their inner mental experiences, and reliably provoked intense emotions. Another study published in 1972 study showed that patients benefited more from the music they were most familiar with and that they also considered romantic and religious music as the most significant. In addition, it was discovered that music could, at times, “guide” the experience of the patient. These early insights on how music affects mental imagery and emotions during psychedelic experiences, and how these, in turn, are associated with increases in therapeutic value, have been validated in more recent studies, one of which was the subject of a Psychedelic Science Review article earlier this year.

Conclusions

The effects of psychedelics on perception have proven to be a longstanding area of interest to psychedelic researchers. This article summarized findings drawn from Aday et al.’s review of the first era of psychedelic research (1895-1975) and focused on the effects of psychedelics on auditory perception in particular. Behavioral studies predominantly from the 1960s and 1970s found divergent findings with regards to how psychedelics affect responses to auditory stimuli; however, they more reliably showed that there were delayed reactions to auditory stimuli across both animal and human models. Early investigations on the neural correlates of psychedelic-induced changes in auditory perception found increases in the amplitude, latency, and peak area of the N1 and P1 auditory evoked potential (AEP) components in cats. Other studies on the neural correlates of auditory changes during psychedelic states suggested that peak DMT experiences temporarily reduced AEP altogether, which can be seen as both anticipating and corroborating contemporary research on DMT.

While some first-era studies maintained opposing stances on the rarity of the phenomenon of auditory hallucinations, other investigations fell more in line with contemporary research which considers auditory hallucinations as pseudo hallucinations that stem from perceptual distortions of objective stimuli. Significant insights on the relationship between music and psychedelic experiences were also produced during the first era of psychedelic science, with many of these insights being validated by current research on music and psychedelic psychotherapy.

Stay tuned for further articles in this series discussing changes in tactile processing, body schema, and time perception brought on by psychedelics.

*From the articles (including references) here :

The Science of Psychedelic Visuals

How does LSD make you hallucinate? Early research on why psychedelics change visual perception already addressed this question.

Psychedelics and Perception Part 2: The First Era of Research

Reviewing early research (1895-1975) on changes in auditory perception.

Last edited: