On January, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism co-hosted a two-day

virtual workshop. The subject was psychedelics as therapeutics.

For three federal agencies to sponsor such an event is as clear of an indicator as any that psychedelic research and treatments have, despite their mostly illegal status, left the confines of the underground. In her closing remarks, Nora Volkow, the director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse,

said,

“With all the attention that the psychedelic drugs have attracted, the train has left the station.”

In January 2023, Oregon will start to accept applications from businesses to run psilocybin service centers. FDA approval of MDMA (for PTSD) and psilocybin (for treatment-resistant depression) looms just a couple years ahead of that. Numerous for-profit companies developing known and

new psychedelic compounds will be ready to produce and deliver these drugs the second they’re approved.

But to extend Volkow’s metaphor, if the psychedelic train has left the station, how far have the tracks been laid out ahead of it? The early data and research on these substances are promising, but in a cultural climate that has become extremely positive towards psychedelics, there’s reason to worry that there hasn’t been enough preparation for negative outcomes amidst the hype.

As psychedelic researchers David and Mary Yaden and Roland Griffiths

wrote in JAMA at the end of 2020,

“Recent popular press books, websites, podcasts, and media reports have uncritically promoted presumed benefits of psychedelics. Patient demand is growing, as is interest in the general population, with the possibility that expectations are outpacing the current data on what outcomes can be confidently foreseen.”

Due to the past stigma around psychedelic drugs, researchers have often focused instead on ameliorating concerns around them. A

recent paper on psychedelic adverse events stated,

“Many–albeit not all–of the persistent negative perceptions of psychological risks are unsupported by the currently available scientific evidence." (One of the authors, researcher David Nutt, linked to the paper on Twitter and

wrote, “Our new paper reviewing the real adverse effects of psychedelics—not the hysteria.”)

In another recent study on the “come down'' many experience after taking MDMA, an open-label study covering just 14 people found that those taking MDMA in a clinical setting did not experience next-day negative effects. The title of the paper, which is not available to read in full for free online, was “Debunking the Myth of ‘Blue Mondays.’” An article from UCSF’s Translational Psychedelic Research Program also recently

set out to rebut the “myths” about the dangers of psychedelics.

While it is important to accurately clarify psychedelics’ safety profile, the move to insist that they are harmless in controlled environments, combined with the growing hype about how “easily” they can address complex conditions like depression or PTSD, leaves a gap in communicating and understanding the myriad of negative side effects that can—and do—occur.

When psychedelics begin to be taken more widely, there

will be a variety of less-than-ideal outcomes, said psychedelic researchers and therapists that Motherboard consulted. There could be sexual abuse and boundary violations from therapists and facilitators,

hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD), psychological or physical side effects, worsening mental health, or spiritual emergencies. There will also likely be people who have disappointing experiences when the miraculous “cure” they were hoping for does not transpire. Nothing works 100% of the time for 100% of people, and infrastructure needs to be set up in advance to support these cases—ideally before psychedelics are made available to millions in legalized settings, like Oregon, or in the medical system through FDA approval.

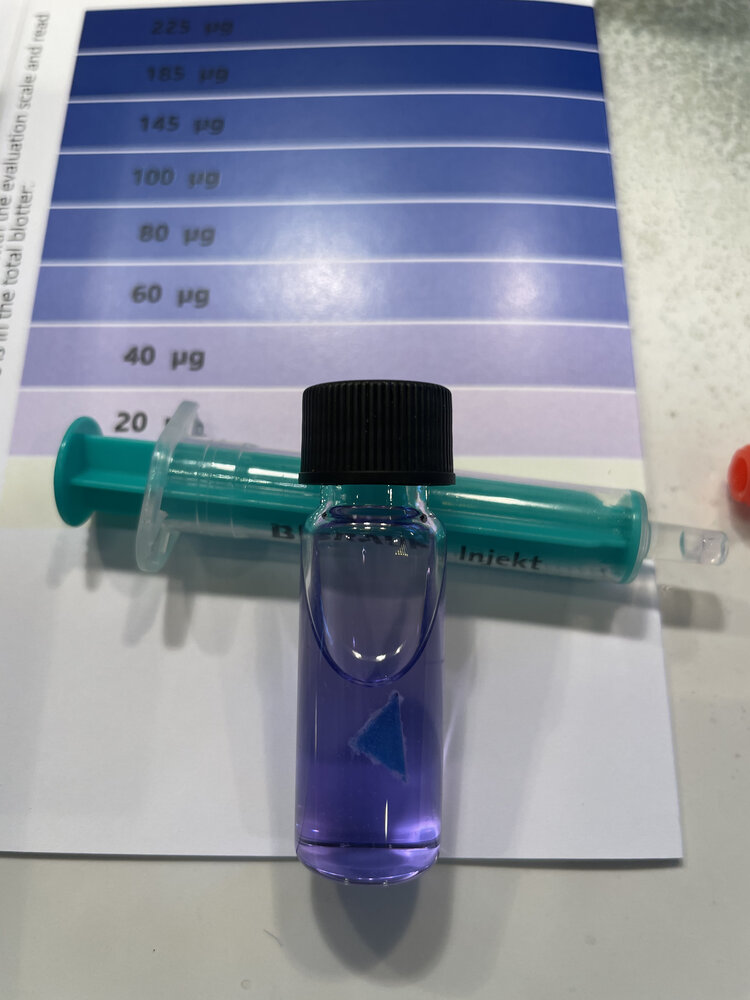

Psychedelics are generally safe drugs: The “classic” psychedelics, like psilocybin or LSD, have been shown to be low risk for addiction, and despite there being some physical concerns, like effects on the heart that should be screened for, users are typically not at risk for serious reactions like overdoses.

But rather than taking that knowledge and promising that there will be no negative outcomes, no ethical transgressions, adverse events, or disappointments, it’s time to start accepting that those things will certainly occur, and setting up frameworks to deal with them. These would include pathways for accountability and reporting harms, as well as dedicating research to study negative outcomes, and how best to help people who experience them.

Part of accounting for future harms means owning up to past harms, too, and what enabled them; current discussion on this topic in the psychedelic community has been prompted in large part by the podcast

Cover Story: Power Trip, co-produced by New York Magazine and Psymposia. Season one of the podcast focused on alleged ethical transgressions by underground therapists, and the difficulty in bringing those to light. Season two, launched on March 1, is focused on adverse events in aboveground settings, like in clinical trials.

One repeated barrier to accountability the podcast reveals is a dedication to the progression of “the psychedelic movement,” along with a lack of responsive official channels and resources for people to measure, follow up on, and report harms. Co-producers and co-creators of

Power Trip, Lily Kay Ross and David Nickles, told Motherboard that they have concerns about history repeating itself in Oregon, where psychedelic services will be first available legally in the U.S.

Owning up to the fact that a significant minority of people may not have beneficial psychedelic experiences is not the same as being anti-psychedelic, or working against the movement. Proving that this community can be accountable and responsible for harms is critical if psychedelic therapy or services are to achieve widespread legalization or medicalization.

“Now is not the time to pretend that these things don't happen,” said Max Wolff, the head of psychotherapy training and research at the MIND Foundation, a European psychedelics non-profit.

“Not talking about possible negative effects isn’t helping anyone. If we want to make these treatments available, if we want them to have a positive impact overall on individuals and society, we have to acknowledge that sometimes people get worse. Researchers need to start talking about it, companies and organizations need to start talking about it, without being afraid that this will turn the tide.”

Psychedelic enthusiasm has led to blindspots in studying harms before. The historian Steven J. Novak

documented how the media exaggerated and lauded LSD and its effects during the 1950s and 1960s.

In 1958, psychologists Sidney Cohen and Betty Eisner presented their work on psychedelic-assisted therapy to the American Medical Association convention. Afterwards, the

San Francisco Chronicle reported on the front page that five LSD treatments were more effective than “the standard sessions of psychoanalysis, which often require hundreds or thousands of hours, and many thousands of dollars.”

This language is uncomfortably similar to how psychedelics can be talked about today, like in advertisements for the telemedicine ketamine company Mindbloom, which include testimonials that claim it can provide “five years of therapy in just a few sessions,” or psychedelic CEO and venture capitalist Christian Angermayer saying in

an interview with Uma Thurman that "psychedelics are like packing 10,000 hours of psychotherapy into four hours.”

In 1960, Cohen began to study LSD’s safety. He received survey answers from 44 LSD researchers on whether any of their subjects had died, died by suicide, or had serious psychological side effects. Not much was reported back to him. From his findings, it was concluded that LSD was exceptionally safe.

“LSD activists read Cohen’s study as if it were a ringing endorsement,” Novak wrote.

But Cohen had asked researchers only for approximations—labs didn’t actually do follow-up studies on their subjects, so they had essentially been guessing on people’s outcomes. Cohen suspected that some complications may have been undisclosed because of researchers’ “guilt feelings.”

It was later shown that labs had withheld serious adverse events. Cohen began to look into abuses by therapists, especially those lacking in qualifications who were charging hundreds of dollars per session and dosing people with LSD up to hundreds of times. A number of complaints began to arise against practitioners who took LSD with their clients, had sexual relationships with their clients, or whose clients had ended up suffering severe psychological consequences. Cohen began to distance himself from other psychedelic therapists, including Eisner.

“Her personal investment in the success of LSD therapy tends to reduce the validity of her results,” he wrote.

The new era of the “psychedelic renaissance” often seeks to

distance itself from the zeal of the past, in terms of study design and ethics. But it’s still the case that most of the research on psychedelics today has still only focused on how effective it is for various outcomes. On the eve of psychedelics' rollout there should now also be rigorous research and attention dedicated specifically on less-than-ideal outcomes too—what kinds there are, and the best ways to respond after they happen.

In the last year there have been a handful of academic papers on difficult psychedelic experiences, but they are focused only on the nature of those experiences, not what to do about them, said Jules Evans, a writer and philosopher who co-wrote

a book on spiritual emergencies. In 2021, one of the

very first papers on integration was published,

“but they were still people with experience in integration, saying this is what I think works well,” Evans said.

“This is my model for it.”

Integration is a word often thrown around; broadly, it means the processing of a psychedelic trip after it is over, “integrating” the experience into one’s life. But the definition of integration is shaky.

“If you think psychedelic therapy is the wild west, psychedelic integration is just as wild,” Evans said.

Currently, if people have a difficult experience, they roll the dice again when they try to seek help.

“I know one person who had a temporary psychosis after taking too many drugs and he went to a healer and the healer said to him these psychological problems were because in a previous life he was a Nazi,” Evans said. Another person Evans knows had a manic episode after taking psychedelics, and went to a shamanic healer in Los Angeles who told them that the problem was they were infested with demons. For those cases, the “integration” was not helpful, but caused further harm.

Evans said there's a lack of empirical evidence as to what kinds of integration are most beneficial for specific negative outcomes. As it stands now, every integration expert has their own model, depending on what their background is. Some integration philosophies may have the belief that a difficult experience is a good thing.

“This kind of thing happened in the ‘60s, where patients would be given LSD hundreds of times until they sorted out the mess,” he said. Evans, with David Luke from Greenwich University and others, is currently starting a research project to study this topic. They want to find people who have had negative psychedelic experiences, and find out how they managed or integrated them.

“We’ll begin to get the first empirical evidence of what helps people,” Evans said.

There should also be a recognition that negative outcomes can occur, even in settings that try their best to be safe, Evans said.

“One of the big banner claims of the psychedelic renaissance is that when we do studies, when people take psychedelics under safe conditions, adverse experiences will hardly ever happen,” Evans said.

“I’m very dubious of that.”

Even in controlled settings, we’ve already seen negative outcomes. In 2019, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS)

released a statement about how a participant in their clinical trial for MDMA in Canada had moved to where her therapists, Richard Yensen and Donna Dryer, had lived after the trial, and that

“the relationship between Richard Yensen and the participant became sexual in nature. Donna Dryer reportedly became aware of this and tried to stop the sexual relationship but was unsuccessful. She did not report it to MAPS or any regulatory agencies.”

When mental health company Compass Pathways released

topline results from its Phase IIb trial of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression last year, there were five patients in the high-dose group, and six patients in the mid-dose group, who experienced at least one serious adverse event, like suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior, after the treatment. That was compared to just one serious adverse event reported in the low-dose placebo group.

Suresh Muthukumaraswamy, a neuropsychopharmacologist at the University of Auckland,

told New Atlas that if those numbers were extrapolated, it would mean that for “every seven patients positively responding to the treatment, one person will experience serious negative outcomes.”

Compass pushed back on the adverse events being related to the psilocybin treatment.

“This assumes a causal relationship between the drug and all the reported adverse reactions—we don’t know that to be the case," Compass wrote in an email to New Atlas. It also wrote that because 11 of the adverse events occurred up to 62 days after the dosing,

“It is not clear that there is a direct link with administration of the drug.” Compass said that the nature of the adverse events may be related to the patients having treatment-resistant depression.

Even if the overall findings of the study were mostly positive, the public and larger research community doesn’t have details or understand what exactly happened in those cases. Rather than pushing them aside, they should be studied on their own. Similarly, in

a small study from 2019, on ayahuasca for depression, four people out of 14 in the active ayahuasca group had to “[remain] as inpatients in the hospital ward for an entire week,” with little discussion in the paper for why exactly they had needed to be hospitalized for that long.

Evans noted that psychedelic research has extremely rigorous screening, meaning there are exclusions for the people who are allowed into the studies, and such stringent exclusions won’t exist in real world clinics. People who drop out of studies can be listed as “drop outs,” rather than as having experienced adverse events.

In 2020, Evans wrote on Medium about how compared to the money invested in psychedelic research, there is almost none dedicated to specifically things that can go wrong.

“There is zero clinical research on how to support people after difficult psychedelic experiences, and perhaps 20 psychedelic support groups in the UK and North America—and these are largely non-profit and run by volunteers,” Evans

wrote.

“Compare that to the billions of dollars being poured into the upside of psychedelics—the miracle cure, the mystical experience, the ‘quantum healing’ you can expect over a weekend.”

He has called for psychedelic companies to commit at least 1% of their capital to integration research and services, which—if the psychedelic market is worth $5 billion—would be $50 million.

Rosalind Watts, a clinical psychologist who worked at Imperial College London during the first depression and psilocybin studies there, thinks that because of the backlash against psychedelics that followed in the 1960s and 1970s, some people feel the need to emphasize positive and simplistic aspects of psychedelics.

“Things have to be completely simple and good, and there's no harm,” Watts said.

“Hopefully now we can recognize that psychedelics are no different than anything else, they’re just tools. We're still human beings. There will be a whole range of difficult human experiences within these sessions, and the whole range of difficulties that come up in psychotherapy will be amplified in psychedelic therapy.”

Watts said that there should be a better safety net for people who participate in clinical trials, past and future.

“They’ve given you their time, their energy to take part in the study,” she said.

“You can't just say goodbye to them six weeks later, and hope everything's okay.”

People could have negative outcomes arise much later than their few integration sessions after an experience, she said. This is well-documented in the

first episode of season two of

Power Trip, in which a participant from the MAPS MDMA clinical trial said that she experienced suicidality once the trial was over.

“I’ve equated it to, like, someone did open heart surgery, you know?” one participant told Ross and Nickles.

“And they tore open my chest and they repaired the little damage in the heart there, but then everyone just walked away from the table and my chest was still wide open. No one’s going to survive that.”

“I kept finding with people that in the six weeks at the end of the study, they were fine in that phase,” Watts said, about the psilocybin trials.

“They were more up and down, but they were fine. They were being checked on. The difficulties happened months later when depression came back or when they didn't feel so supported anymore.” She’s now launching an online integration group called

Acer, which will last for 12 months.

During the Imperial study, Watts said that many complex reactions arose that she and others didn’t feel completely prepared for. One patient, for example, had the experience of becoming his grandfather when his grandfather was drowning at sea.

“For a long time afterwards, he felt really low because he didn't have that uplifting connectedness experience,” Watts said. He felt the horror, the loss, the pain that his grandfather had felt, at the point of dying and knowing that he was going to be leaving behind his children. It was difficult for Watts to support him at first, and she needed support from others to weigh in on how best to help.

“In a way this is nothing to be ashamed of,” Evans said, of complex and negative experiences.

“It’s not surprising that if people have a massive shift in their personality, that they could be in a very vulnerable state afterwards. Did we really think that patients could have their ego dissolved and reformed overnight, and then they just go back to their lives and no big deal?”

It’s also crucially important to study experiences where someone doesn’t experience much at all. Given the immense promotion of psychedelic treatments today, it’s easy to imagine that this will be a particularly difficult experience for people who have high hopes that aren’t lived up to.

“I suggested it should be called the ‘meh’ experience,” Evans said.

“You've got the mystical experience and then the ‘meh’ experience, which is just like, meh, nothing happens. And the more we hype it, I’m sure the more that will happen.”

Before psychedelics are granted FDA approval, Oregon will be the first place in the U.S. where they are legal. The state is currently attempting to create a regulated, legal model for psilocybin services for adults. Key factors that will help in being cognizant of negative outcomes will be the training that therapists and facilitators receive, as well as the systems in place to help people report when things have gone wrong.

Motherboard reviewed over 30 hours of recordings from the Psilocybin Advisory Board and its subcommittee meetings, and found that board members were continually wrestling with issues around safety and accountability.

“The training and licensing structure ensures that practitioners are accountable to safety, practice, and ethical standards,” said Tom Eckert, the chair of Oregon’s Psilocybin Advisory Board.

“Transgressions and less-than-optimal outcomes can still happen, but you need mechanisms for accountability and improvement. You need strong standards around training. You need channels for feedback and for making formal complaints to a body that is resourced to investigate when necessary. That is what a regulated model offers.”

As of now, there are still many unanswered questions still about how training and accountability will be enacted in Oregon, even so close to services becoming available. There are draft rules that cover what each training program in Oregon must cover, which has nine modules making up 120 hours. Some modules are eligible for “accelerated training hours,” meaning that if a person can demonstrate they have prior experience, they can move through the module at a quicker pace. The modules on Cultural Equity in relation to Psilocybin Services, Safety, Ethics, Law and Responsibilities, and Preparation and Orientation can not be accelerated, and accelerated hours can’t be more than 40% of the total hours requirement.

There isn’t yet guidance on how people will evaluate the experience eligible for accelerated training hours. The recommendations from the board have so far advised that it’s up to each individual training program. Eckert said that the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) doesn’t yet have the procedures for training programs to apply for program approval.

Ismail Ali, the director and counsel of policy and advocacy at MAPS, said it might be difficult to codify the importance of integration. Could it be mandated? Could facilitators be held accountable if their client doesn't show up for integration? There could be other ways to ensure that integration is encouraged through regulation, Ali said, like not allowing service centers to separately charge for integration—but requiring that it’s included in the cost.

“I’m sure the OHA will create a detailed application process based on training program rules, which should be made available in May,” Eckert said. Outside of the module outlines, there isn’t yet any details about the content of what must be taught in each module. For example, in terms of integration, there are 14 hours in the training that have to be dedicated to it. The draft rules state that must include “exploration of negative feelings from psilocybin session” and “integration tools and techniques,” but no further specifics yet.

Nickles said he also finds it troubling that the psilocybin advisory board has been promoting conflicting messaging about whether Measure 109 primarily confers psilocybin therapy. Technically the law is for adult use of psilocybin services, and a person doesn’t have to have a diagnosis to seek out those services; nor do people who apply for licenses to be facilitators have to have mental health credentials.

But the

first page of the Measure describes the mental health burdens in Oregon, and that along with setting up adult use services, the bill should

“Examine, publish, and distribute to the public available medical, psychological, and scientific studies, research, and other information relating to the safety and efficacy of psilocybin in treating mental health conditions.”

“[Measure 109] exists within a cultural climate where psychedelics are being hailed as this miraculous medical intervention,” Ross said.

“I don't think you can get away from that, even if you brand it differently.”

Ross said that Measure 109 has been talked about as a way for people to access medical or mental health interventions who don’t have health insurance, another troubling pathway to negative outcomes, in her opinion.

“What happens when you're promoting an intervention like this that is not fully tested but is being approved by ballot measure, not FDA processes and then being rolled out to marginalized and vulnerable populations?” Ross said. “There's a history of medical experimentation on marginalized and vulnerable populations. It does not go well.”

Power Trip documented the stories of people who sought out underground psychedelic therapy for help and found themselves in unequal power dynamics with facilitators who pushed methods and relationships on them that were unwanted. It highlighted how when people tried to come forward with these issues, they were often ignored, or told that their difficult experiences were just part of the process. This is the kind of pattern that legal psychedelic services that are forthcoming should seek to address and correct, but Ross isn’t optimistic. She said that even as the podcast has revealed ethical transgressions of people in the psychedelic community, there still hasn’t been any movement to address such issues.

“There have been ample opportunities to grapple with case studies and implement realistic structures for holding people accountable and ensuring that folks who have been harmed get help,” Ross said.

“That has not happened in the decades that there has been an active, psychedelic underground.”

As one example, a subject in

Power Trip is Francoise Bourzat, a psychedelic therapist who trained several of the therapists that allegedly violated boundaries and is married to

Aharon Grossbard, who is accused of abusing a client. Bourzat has also held an unofficial advisory position to Oregon’s training subcommittee.

Last June, Bourzat visited the board as an expert panelist.

“The training of facilitators is essential for me,” she said.

“As you know, I have been involved in this training of facilitators for over 25 years. What I've learned from my work is that it is important that everyone has a psychological foundation because once people approach this experience, regardless of their intention, material is going to emerge.” Training materials dated from May of last year list Bourzat as an advisor. Last year, Bourzat’s name was still listed on training materials.

“I haven't heard anyone involved in that top level of the Psilocybin Services initiative talking about the proximity of Bourzat to this program,” said Nickles.

“We're talking about people who have been alleged to have engaged in patterns of abuse over decades, and are in incredibly close proximity to this measure and nobody's talking about it.”

When asked directly about Bourzat’s influence on the board, and whether the board would address the allegations against her publicly, Eckert said in an email:

“The Board remains focused on making recommendations to the Oregon Health Authority that support the safe and ethical facilitation of licensed psilocybin services in Oregon. Sheri and I developed Measure 109 to ensure safe practice through accountability, which is achieved through required training, licensing, and adherence to a code of ethics. Oregon's Psilocybin Services Program, unlike unregulated or underground activities, establishes a government agency to process complaints and initiate investigations as needed when ethical issues arise with licensees. This is important and a big reason why we approached things the way we did.”

“It's totally in line with what we've seen as far as undisclosed relationships,” Nickles said.

“There are clear indications that whether it's social networks, professional networks, or otherwise, there are a number of behind the scenes relationships between a number of figures who are active within psychedelia, which I have major concerns about.”

When reached for comment, Bourzat said in an email,

“I am unsure of the sources of what is being conveyed in this Podcast. Yes, I was affiliated with the campaign board of the Oregon Initiative, certainly not asked to be involved in writing any of the regulations for the roll out of this initiative. I leave it to the current team to decide what guidelines they would suggest for ethical topics. I have always been acutely aware of the need of such ethical guidelines and of ways to be supportivee to both clients and therapists who are strugglng with situations involving the crossing of boundaries of complex dynamics, may they be around power dynamcs, ruptures of therapeutic relationships, sexual transgressions.”

When psychedelic therapy was underground, without any regulatory structure, there was no way to hold people accountable besides law enforcement—which could also put an accuser at risk since they would be admitting to illegal activities.

She said that the OHA has the authority to investigate an applicant, a licensee, or a former licensee, but to deny or take away a license requires an investigation. OHA can issue subpoenas, which compel somebody to provide testimony or documents, they can require the attendance of witnesses at a hearing, and go on the premises and do an onsite investigation.

They also have the ability to do an immediate suspension of a license in emergency cases, and have a hearing be held after the fact, if they find there is a serious danger to public health. There will be a complaint system set up. If someone files a complaint, then the agency has to issue a notice to the party that’s been complained about, and there will be an investigation. O’Fallon said that a complaint has to include very specific sections of the statutes or rules that are alleged to be violated.

Board member Kimberly Golletz asked what would happen is a facilitator sexually assaulted a client where that would fit into the disciplining. O’Fallon said that once there are rules established that say facilitators have to comply with a code of ethics; if they violate that code, then OHA can step in to take licensing action.