MDMA and LSD drug testing kits that could save your life

Danielle Simone Brand | Double Blind | 10 April 2020

Everything you should know about

'the best MDMA and LSD test kits on the market.'

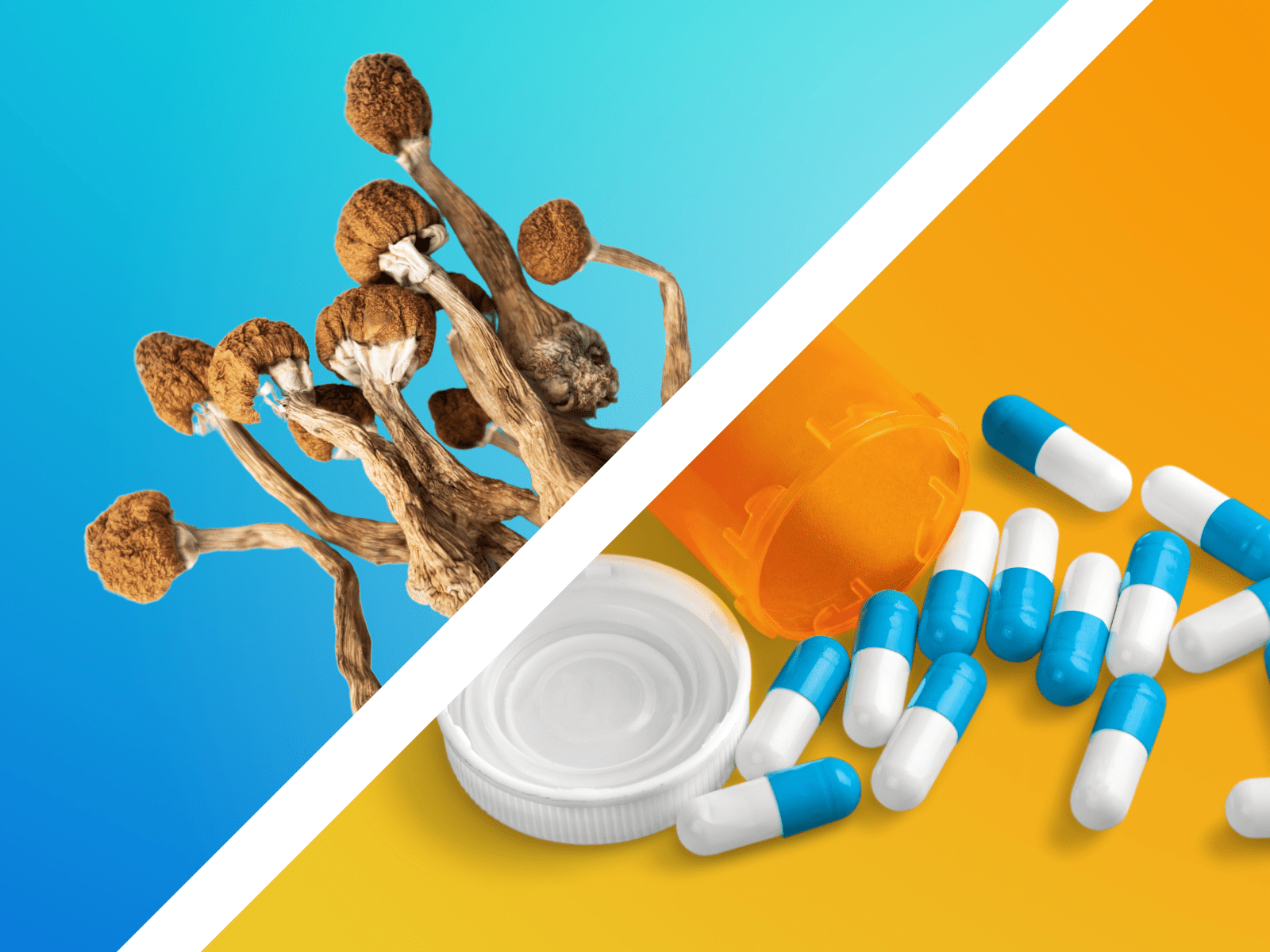

Drug testing, sometimes called drug checking, is an essential harm reduction tactic to ensure that a substance is truly what you think it is, and not adulterated by potentially toxic chemicals that could cause an unpleasant or fatal reaction.

The best thing about drug checking is that you don’t need a whole chemistry lab to do it! In fact, you can test your drugs in the privacy of your own home with a drug checking kit such as for MDMA or LSD. Indeed, drug checking is easy, requiring only a few reagents (liquid testers) to ascertain whether your substance is pure, or contains other elements.

Alexander Shulgin

MDMA

MDMA first surfaced as a psychotherapeutic aid in the 1970s. Though analogs of the drug had been synthesized earlier, most sources credit chemist Alexander Shulgin for discovering the formula, along with psychotherapist Leo Zeff for helping bring its psychotherapeutic properties to light. Because of MDMA’s particular euphoric and empathic influence on the user, it showed promise in therapeutic settings for healing trauma and promoting personal and spiritual growth. In the 1970s and 1980s, early adopters caught word of the molecule’s recreational uses, and by 1985 MDMA was listed in the U.S. as a Schedule I drug.

Effects of MDMA

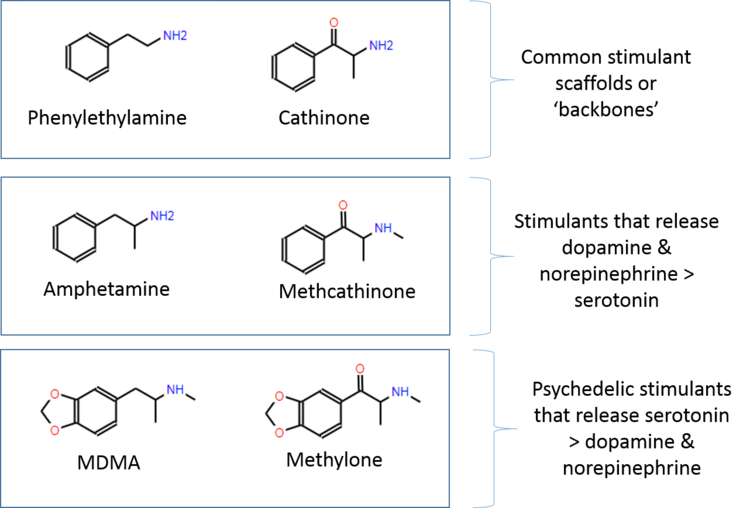

MDMA causes your serotonin neurons in the brain to release larger amounts of serotonin. It also causes the release of dopamine neurotransmitters, as well as oxytocin and prolactin hormones. This effect can lead to feelings of euphoria, greater willingness to communicate, decreased fear, increased connection to others, and feelings of love or empathy.

MDMA moreover decreases activity in the amygdala, which is where memories are stored. This effect, coupled with those listed above, is why MDMA has been so useful in treating PTSD, which the nonprofit MAPS is currently investigating. In fact, MDMA for PTSD has been placed on the FDA fast track to become an approved medication in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy early this decade. MAPS is currently in the third and final phase of FDA-approved research.

On the physical side, MDMA may cause loss of appetite, shivering, feelings of restlessness, or even feelings of warmth. It’s important to note that MDMA should not be taken on a regular basis, as for some, there is a comedown, which entails the time it takes for your brain to replenish its serotonin.

How long does MDMA last?

The total duration of MDMA is about three to six hours, with an initial onset of 20 to 90 minutes.

What does MDMA look like?

MDMA often comes as a white or light brown crystalline powder, contained in a clear capsule. Sometimes it may come as light brown rocks. In other cases, especially if you’re taking ecstasy (which may contain other components beyond MDMA), it comes as a pressed pill, which may be a variety of colors and feature a design.

Why you should test your MDMA

According to Emanuel Sferios, founder of

DanceSafe, MDMA prohibition has created 'the most adulterated market in history.' Over the last few decades, hundreds of drugs have been sold as ecstasy or molly that contain little to no MDMA. Of the numerous counterfeit drugs

DanceSafe has tested, dangerous cathinones (a.k.a. “bath salts”) and meth surface frequently. While these MDMA counterfeits may yield psychoactive effects, they won’t likely feel as pleasurable or expected as those of MDMA. And, in the wrong doses, they could also be fatal.

Sferios was first introduced to MDMA as an informal therapy that helped him process difficult experiences from childhood. About a decade later, a friend brought MDMA back to his attention as a party drug—a use that resonated with Sferios, given its ability to boost energy, euphoria, and social connection.

“I was blown away when I went to my first rave in Oakland—by how beautiful the culture was,” he tells DoubleBlind, citing the diverse demographics and peaceful vibe he found. By that time, MDMA had become the most sought-after rave drug and prohibition was well underway; the substance that Sferios had known to be both fun and therapeutic was being widely publicized as dangerous.

“No one is saying that MDMA use carries no risk,” Sferios says. Consumers of an unadulterated version of the drug can suffer adverse effects, and even die, if they take too large of a dose, or drink too much or too little water during the roll. But the risks grow when those who believe they’ve taken MDMA have actually taken meth, PMA, cathinones, or something else entirely. To be ultra-clear: It’s counterfeiting—which results from prohibition, and an unsupervised black market—that poses the biggest risk; in the right doses, and with a thoughtful set and setting, taking MDMA is a fun, transcendent, and even therapeutic experience for many people.

The MDMA-associated deaths in the 90s and the subsequent media villainization of the drug prompted Sferios to found

DanceSafe in 1998. The organization’s mission is to educate consumers of club drugs and to encourage and facilitate testing for risky counterfeits. Altogether, DanceSafe’s four staff members and hundreds of volunteers practice a philosophy known as harm-reduction that’s gained traction in Europe but has yet to receive widespread credit in the U.S. The idea behind harm reduction is simple: to reduce the negative consequences associated with drug use.

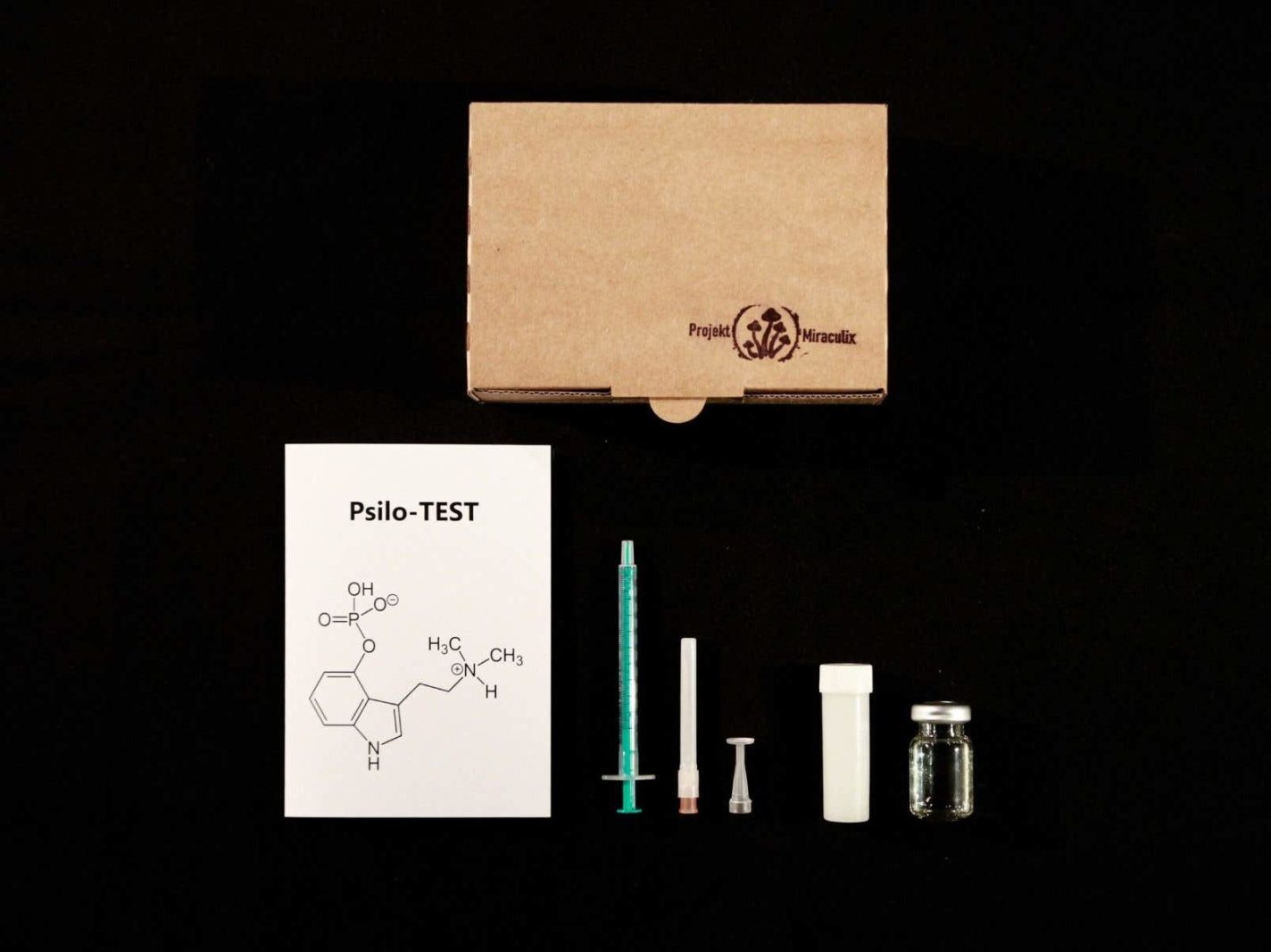

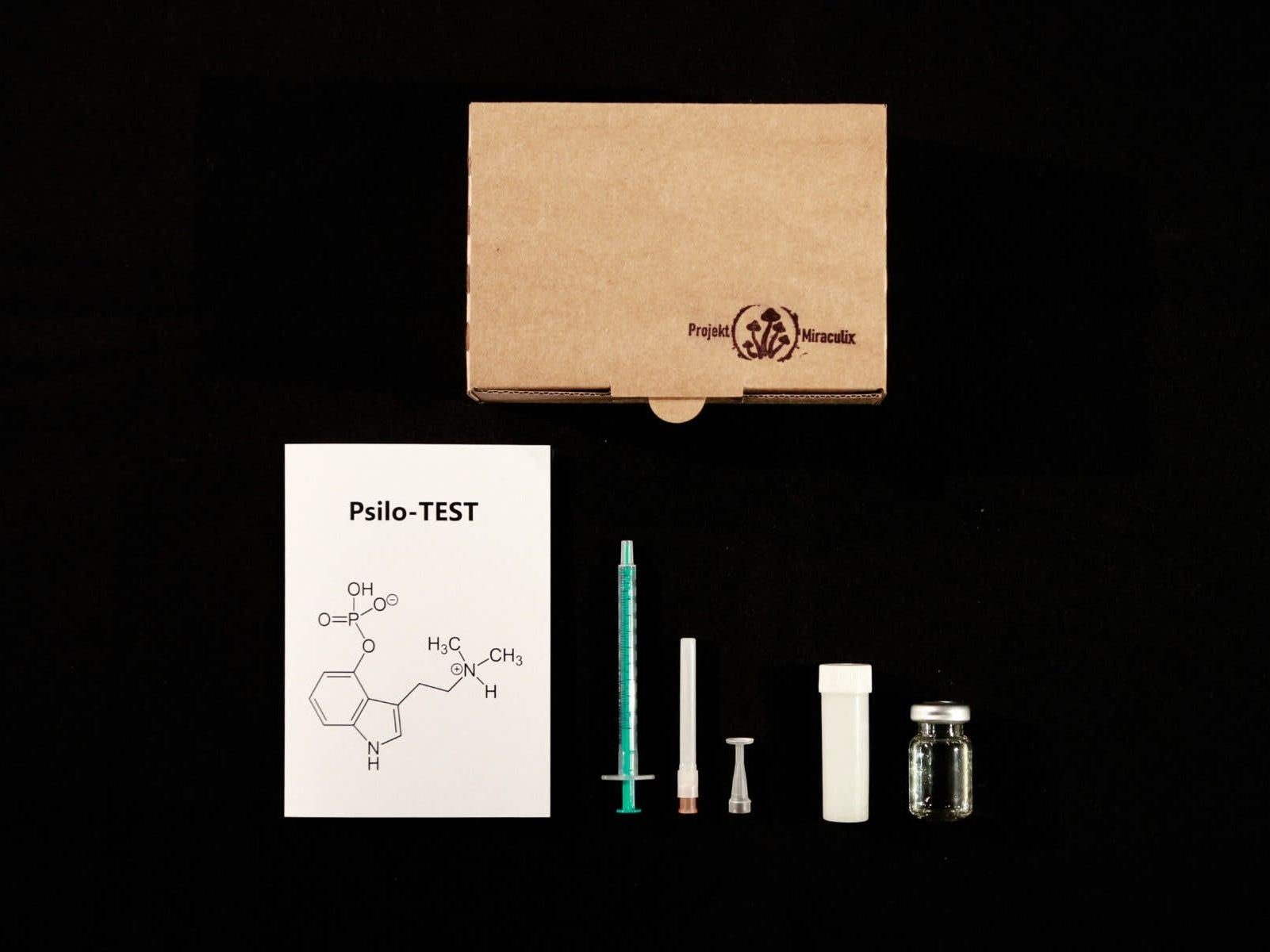

MDMA test kit

Of the two testing methods used by

DanceSafe, one employs infrared spectroscopy, which can yield detailed information about a molecule. But testing by means of spectroscopy involves funding and staff hours to utilize the machine at festivals.

The other method is much more cost effective and can be done at home by anyone.

DanceSafe offers testing kits for MDMA, LSD, and a number of other compounds, both online and at festivals. The point of the MDMA and LSD testing kits is to tell you whether the primary ingredient is what you intended to consume.

Testing is critical, says Sferios, because you can’t reliably identify MDMA or LSD by look, smell, or taste.

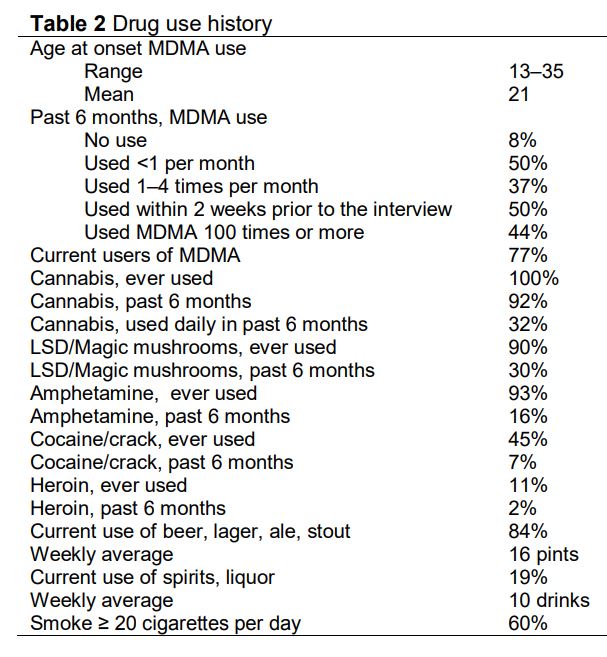

MDMA testing at a glance

- Common MDMA counterfeits: PMA and PMMA (two compounds producing similar effects to MDMA but with more toxicity), cathinones (aka “bath salts”), and methamphetamine

- Risks of consuming counterfeits include: hypertension, elevated temperature, difficulty breathing, and death

- Most counterfeits don’t contain any MDMA

- Roughly 80-90 percent of what’s sold today as MDMA is authentic; as recently as 2015, that figure was closer to 30 percent

- Fentanyl, the dangerous synthetic opioid, hasn’t cropped up on the MDMA market yet, though some observers think it could soon

-

DanceSafe MDMA kits contain one free fentanyl test strip;

additional fentanyl strips can be purchased separately*

- MDMA test kits include three reagents, or liquids that turn color in the presence of particular chemicals: Marquis, Simons, and Froehde

- Used together, these reagents can reliably determine whether MDMA is the main ingredient in a pill—though they can’t indicate absolute purity

- Follow all steps in the kit. Read the testing kit instructions in advance, and be sure you’re sober when you test.

Albert Hofmann

LSD

LSD is a 'classic' psychedelic that was initially synthesized in 1938 by chemist Albert Hofmann, who was working for the Swiss company Sandoz Pharmaceuticals. Hofmann had intended for it to be used as a respiratory and circulatory stimulant, without having realized its psychoactive properties. It took him another six years to rediscover and appreciate its psychedelic qualities: First he accidentally ingested a little bit of LSD on April 16, 1943, and three days later intentionally tried it on April 19 and wrote a bicycle home, high on LSD. This day is now celebrated as the holiday Bicycle Day.

Effects of LSD

LSD binds to several 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptors in the brain, which causes an excess of serotonin in the synaptic cleft between neurons. LSD can alter perception, mood, and cognitive processes by acting on the serotonergic system. It also acts on the dopaminergic system, which affects processes like learning, reward systems, and motivation. The increased levels of dopamine and serotonin can make LSD feel energetic and provide an extroverted experience.

LSD can enhance the imagination and senses, stimulate thoughts, cause feelings of euphoria, universal connection, or on the flip side anxiety or paranoia, and can produce hallucinations. As a classic psychedelic, LSD in high enough doses may cause temporary ego dissolution that can result in mystical experiences and a sense of transcendence.

Prior to it being outlawed by the Nixon administration under the Controlled Substances Act, LSD was used as a powerful tool in psychotherapy. Today, researchers are returning to LSD as a tool for addiction treatment, as well as for anxiety, depression, or other conditions.

How long does LSD last?

The effects of LSD can last anywhere from eight to 12 hours, or in some cases even longer.

What does LSD look like?

Most often, LSD comes in the form of a liquid, or as a tab (upon which that liquid has been dispersed with a dropper), torn from a piece of perforated paper. In other cases, LSD may appear in the form of tablets, capsules, or gelatin squares.

Testing LSD

The LSD market looks a little different from MDMA. Until recently, LSD counterfeits weren’t considered especially risky. But the influx of a class of drugs known as NBOMes about ten years ago changed that. Variants of NBOMe, which stands for

N-benzyl methoxy, simultaneously thicken the blood and constrict vessels, potentially causing heart attacks, renal failure, or stroke. Fentanyl and analogs like carfentanyl also appear as counterfeits or adulterants in the LSD market today.

While Sferios notes that in recent years, the illicit markets have, to some degree, cleaned themselves up (with certain distributors now refusing to sell fentanyl or fentanyl analogs for instance), a staggering array of new, illicit compounds and research chemicals hit the market every year. Besides prohibition and growing demand, factors contributing to the illicit market today include the rise of the dark web and the cover of anonymity provided by cryptocurrencies.

When it comes to the intentions of illicit manufacturers and dealers, Rachel Clark, who works in communications and development with

DanceSafe, gives these folks the benefit of the doubt.

“The purpose [of selling counterfeit drugs] is not to kill people,” she tells DoubleBlind.

"Instead, some manufacturers and dealers are likely unaware of the ins and outs of new molecules or research chemicals which, in some cases, mimic the effects of the better-known drugs, but carry more risks. Some may not even know the origins of what they’re selling.”

Testing LSD at a glance

- The last decade has seen a proliferation of drugs sold on blotter paper resembling LSD, but with high levels of toxicity

- NBOMes mimic the effects of LSD but carry significantly more risk; the analog known as 25i NBOMe is highly toxic

- Between 2013 and 2016, roughly one person a month died after ingesting an NBOMe sold as LSD; fortunately, the rate has since slowed

- Carfentanyl, an extremely potent fentanyl analogue, is—like LSD—active at the microgram level. Because it’s sometimes sold on blotter paper, confusion between the two drugs can arise.

*

- The DO series of drugs, including DOB and DOC, are psychedelics, sometimes sold as LSD, that typically have longer lasting effects and are not well-documented for safety

- LSD test kits are simpler than those for MDMA: Ehrlich’s reagent turns purple in the presence of LSD or closely related drugs. According to Sferios,

“If it turns purple it’s pretty much going to be LSD, or a prodrug of LSD like 1P-LSD or ALD-52.”

Drug testing and the law

Law enforcement and harm reduction efforts have a checkered relationship. For instance, about half of U.S. states have laws on the books criminalizing testing agents and paraphernalia. But when it comes to testing, these laws are rarely enforced. To Sferios’ knowledge, no one with

DanceSafe—staff, volunteer, or festival-goer—has ever been arrested for participating in drug testing. In some cases,

DanceSafe works under amnesty agreements with local law enforcement—which makes sense from a humane standpoint, considering the fact that fewer deaths and injuries occur when testing and other harm-reduction strategies are at play.

The psychedelics renaissance and drug testing

There are many reasons for the comeback of psychedelics. They’re a productivity hack in small doses and a socially-bonding tool made for dancing. They also help quench the yearning many of us have to understand the self in relation to the whole—to see past artifice and step into another way of being. Because of psychedelics’ potential therapeutic uses for PTSD in particular, Sferios theorizes that the current renaissance is a means of collective healing from 9/11—and today, in the midst of the Covid crisis, we may see even more relevance for the therapeutic uses of psychedelics.

But, as long as prohibition endures, the counterfeiting problem will remain.

“The more successful the Drug War is at cracking down on real MDMA and LSD,” said Sferios,

“the more motivation there’ll be for developing and selling counterfeits.”

We may earn a commission from links on this page, but we only feature products we back. Drug Testing Drug testing, sometimes called drug checking, is an

doubleblindmag.com