mr peabody

Bluelight Crew

Becoming a Psychedelic Researcher

Sewell, Baggott, Cozzi, Doblin, Forte, Goldsmith, Goodwin, Guillot, Hanna, Holmes, Jerome, Kumar, Lovett, Merkur, Onnie-Hay, Peden, Roberts, Ruderman, Sachs, van Vee

With the current renaissance in psychedelic research, after a forty-year moratorium, undergraduates interested in the topic are increasingly starting to ask: How can I get involved? Unfortunately, psychedelics are still heavily stigmatized, and there is as yet no obvious infrastructure into which enthusiasts can channel their energy. There are no psychedelic research graduate programs, no psychedelic student groups, no psychedelic scholarships, and few professors willing to provide mentorship or funding agencies willing to sponsor such research. This leaves undergraduates inspired by psychedelics frustrated and uncertain about what they should be doing in order to most help the cause. Here are some suggestions and guidance for those so perplexed.

First, examine your motives for entering psychedelic research. Is it because psychedelics are novel and cool? If so, you are apt to find psychedelic research disappointing. While Dr. Timothy Leary, perhaps the most famous of the psychedelic researchers, found it a route to enduring fame and hot sex with large numbers of young women, he did this primarily through his showmanship rather than his scientific research. If such a lifestyle is appealing to you, there are shorter routes to this goal than decades of scholarly study.

Or is it because you have had a mystical or life-changing experience on a psychedelic? You do not need to become a psychedelic researcher in order to continue your self-exploration; you do not even need to continue to take psychedelics, as there are many other methods of changing one’s own consciousness, from yoga to meditation to Holotropic Breathwork. Such a path may prove profoundly self-altering; however, it is unlikely to change society.

Or is it because you are frustrated living in a culture that tramples individual freedoms, discourages introspection and insight, substitutes lies and half-truths for genuine science, encourages people to self–censor and conform to that which they know is harmful and wrong, and that you wish instead to change society for the better? You do not need to be a scientific researcher in order to be an activist. Ultimately, scientific research is only useful as a tool in the hands of the activist, for it is the activist who compels society to improve.

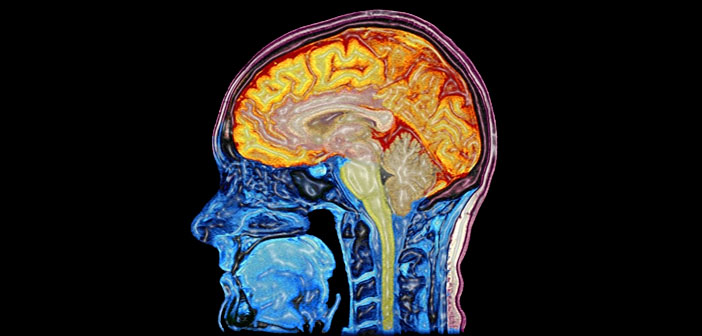

Or is it because you are motivated by a genuine curiosity about these peculiar substances, and wish to apply the tools of modern inquiry toward understanding their properties? Perhaps you appreciate that scientists such as Ralph Abraham, Stephen Jay Gould, Carl Sagan, Andrew Weil, and Nobel Prize winners such as Francis Crick, Richard Feynman, and Kary Mullis have found psychedelics valuable tools in formulating their great discoveries, and wonder how this can be so? Maybe you know that the discovery of LSD was what sparked interest in the serotonin system and prompted the explosive growth of modern psychopharmacology that continues today? Possibly you contemplate what other wonders may lie hidden in the closed box of psychedelic science?

And are you willing to accept that your unconventional interests may lead to professional isolation or even ostracism, and that the time-consuming navigation of the layers of red tape endemic to psychedelic research will inevitably slow your publication rate and consequently promotions compared with your peers? And are you aware that the total lack of government or corporate support for such endeavors means that you will never be rich, and you may in fact eventually land in jail on trumped up charges of one sort or another? If such considerations do not trouble you, then read on.

As an undergraduate get your degree! Lie low and infiltrate the System

The undergraduate years are a difficult time for the nascent psychedelic researcher because of the stigma that these drugs still hold. Many undergraduates come to realize that broadcasting their unconventional views at this time could potentially harm their future careers, and thus indirectly harm psychedelic research. Sometimes we have to conform to others’ expectations in order to establish a solid base of credibility, and wait for a time when we can be more independent in our pursuits. The book Why Shrooms Are Good by Joe Schmoe is likely to be ignored; Therapeutic Benefits of Psilocybin by Dr. Joe Schmoe considerably less so, even if both books say exactly the same thing. Incidentally, this was the path I followed; I didn’t breathe a word of my interests until I was already on the faculty of Harvard Medical School. Be warned, however–conformity for too long can corrode the soul. And in retrospect, you are freer as an undergraduate than you may think you are.

Educate yourself about psychedelics

Read what scientific literature does exist regarding psychedelics, not just the material that draws popular attention. If possible, take a course in psychedelics. Dr. Stacy B. Schaefer teaches a class on Indigenous People of Latin America at California State University, Chico, dealing in part with the peyote-using Huichol Indians. Dr. Constantino Manuel Torres teaches an Art and Shamanism course at Florida International University, exploring traditional cultures that use psychedelics. Northern Illinois University offers regular courses by Dr. Thomas Roberts. Invite him to be a guest lecturer at your own school! Dr. Roberts writes:

If your department or another would like to offer either course – Foundations of Psychedelic Studies, or Entheogens – Sacramentals or Sacrilege? – to students (graduate or undergraduate), it might be possible for me to travel every now and then and meet with a class, say over long weekends or for a day or two every couple of weeks. The rest we can do by Internet.

Alternately, design your own independent study course (or courses) for credit in psychedelics. This is the approach MAPS President Rick Doblin took for his undergraduate education at New College of Florida. Use Dr. Robert’s syllabus as a basis. Paul Goodwin is starting a web site aimed at interested students offering links and short descriptions of courses relevant to psychedelic studies. This should be online by the fall of 2006 (www.psycomp.org.uk). Keep current with the literature in your area of interest, and start thinking about ideas for your own research project.

Another graduate student writes:

I completed an honors thesis as an undergraduate, which basically was a literature review, and it ended up resulting in my first publication a few years later. It also led up to my masters thesis (a quasi-experimental study) and a few other papers in press. The best thing undergraduates can do to help is to prepare themselves, I believe. Be persistent about being a part of psychedelic research, if that is truly where your heart lies. I may not be able to do exactly what I want right now, but I still can keep it in mind for the future.

“The Implications of Psychedelic Research for XXX” often makes a good term paper topic. Rephrasing a title as a question is one tactic to use when encountering skeptical professors: “Do Psychedelics Have Implications for XXX?” or “How Should We Evaluate Psychedelic Claims of XXX?” Also, consider requesting that your local and school libraries acquire psychedelic books. Not only does this help spread knowledge, it also helps authors and encourages publishers to accept more psychedelic titles.

In the meantime, attend a convention! There’s quite a bit of psychedelic research presented at the yearly Society for Literature, Science, and the Arts conferences (http://slsa.press.jhu.edu). Similarly, the Toward a Science of Consciousness conferences held in Tucson, Arizona every other year also always have some presentations dealing with psychedelic research (www.consciousness.arizona.edu). And more specifically focused on psychedelics and altered states are the yearly Mind States conventions, where aboveground researchers and underground psychonauts congregate to discuss their latest discoveries. The Mind States emailing list provides updates on similar events that happen worldwide (www.mindstates.org).

Underground publications often present cutting-edge discoveries in the arenas of psychedelic chemistry, botany, and pharmacology. The Entheogen Review, for example, was the first place to discuss the extraction of tryptamines from Phalaris grasses for ayahuasca analogues and the first to confirm the psychoactivity of Mimosa tenuiflora (= M. hostilis) without coadministration of a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. These days, countless web sites and discussion forums carry first-person reports of the latest synthetic psychedelics and botanical preparations. Amateur science flourishes in our current legal situation, in which professional science is so difficult to perform that most discoveries have to be made underground. Remember, though, that the rigorous controls present in aboveground science are usually lacking in underground efforts, rendering many results questionable at best.

Start a psychedelic student group

While one undergraduate is easy to intimidate, large groups of them have a history of occupying administration buildings to facilitate societal change. Fish travel in schools for a reason! Another strategy, therefore, is to start a student group. One possibility would be to form a chapter of a national organization such as the Marijuana Policy Project (MPP) or Students for Sensible Drug Policy (SSDP). This approach would be similar to student chapters of Greenpeace, Amnesty International, or Students for a Free Tibet.

One notorious troublemaker writes:

I took out an ad in the school’s newspaper, Come to the first meeting of the University of Chicago Education Society. We met at the spot that marked the beginning of the Atomic Age, a Henry Moore sculpture called The Nuclear Egg. About a hundred people showed up. We shared stories, brought speakers to town, dreamed of a saner world, and labored to manifest one.

At Harvard, where I work, there is no recognized undergraduate student organization focused on psychedelic research. The procedure for creating such an organization can be found on-line at: www.college.harvard.edu/student/handbook.pdf. The advantages of forming a recognized student organization are many. Not only can recognized groups get permission to use campus facilities and assembly halls for events and symposia, they are also eligible to apply for funding from the student government. A student organization focused on psychedelic research could engage in outreach with other student groups and academic departments encompassing most of the physical, biological, and social sciences, as well as those pertaining to the arts, humanities, and civil liberties. Events could be held on campus to educate and inform, and university funds could be used to bring in speakers and arrange conferences. Such events could draw participants from all over the world. While these activities do not necessarily amount to actual psychedelic research, they could be fashioned in a manner to do so, if, for example, a faculty member were enlisted to supervise a survey-based study. More importantly, student organizations spread awareness, generate understanding, and de-stigmatize psychedelics, thereby helping to set the stage for actual research when the time and place are right.

SSDP and the student ACLU group helped sponsor the ethnopharmacology society’s seminar on the co-evolution of plants and humans. We also were awarded a grant from the student organization office–raising more than a thousand bucks!–and were able to bring in Dennis McKenna as the outside speaker. It was a splendid event, with Dennis giving a great talk examining plant chemical communication signals that may be driving the interesting side of human evolution. It was followed by a panel discussion that included some of University of Washington’s botany professors, a classics scholar, and an Incan medicine man.

Volunteer

umerous organizations exist that appreciate people who offer to do volunteer work. MAPS needs help with their on-line psychedelic bibliography, creating abstracts for many of the articles that are listed. The Erowid web site also sometimes uses volunteers (see www.erowid.org/general/about/about_volunteers.shtml). Find an organization with which you resonate and contact them to see what sort of help they need.

Write letters

Without government approval, psychedelic research will stagnate as it has for the last forty or so years. Government politicians, agencies, and organizations need to understand that people interested in psychedelics are not thoughtlessly promoting drug use, but are sincerely searching for personal and scientific truths. Write letters and share how you feel! Nobody can arrest you for an opinion–yet.

Donate money to psychedelic organizations

This is by far the easiest way to get involved. With no support from government or industry, that means that funding for psychedelic research is going to come from one place only–you!

As a graduate student

Your first stop should be the Heffter Research Institute’s Scientific Advisory Panel, which is a list of psychedelic allies in the international academic world. The locations where these individuals work are areas where there is possible support for psychedelic research.

Failing this, Dr. Alexander Shulgin’s recommendation is to get as strong a foundation in graduate school as possible. Work in a highly-respected institution with good people doing solid, reputable research, pick up as many skills as you can along the way (for you never know which will ultimately be useful) then pursue what it is that you genuinely want to do, which you might not even know until after graduate school anyway. Learn solid methodology and techniques, gain as much knowledge as you can, hone your analytic skills–while keeping sight of the big picture–and then apply all these resources to psychedelic research when the time comes. The more rigorous and stringent your research and its interpretation, the harder it will be for people to argue with it, reject it, or not take it seriously–and that can make all the difference. If you try to get as much as you can out of graduate or medical school, you’ll always have those tools, analytical skills, and knowledge of sound techniques available to do excellent research in whatever field you choose. In addition, it is important to have proficiency and credibility in a field other than psychedelic research, to serve as a fallback position when changing political winds make times tough.

My own path was one of going to medical school and becoming a medical doctor, which I figured was a necessity if I ever wanted to actually give these drugs to people, which I do. Furthermore, I believe that an M.D. sometimes has more credibility than a Ph.D. or politician when it comes to telling people what’s good and bad for them. My grant proposals can afford to be a little more daring because if they’re all turned down, I won’t be living on the street–seeing patients for money is always an option. One disadvantage, of course, is the length of training–which in my case (neurology/ psychiatry) was ten years after college. Another disadvantage is the large loans and consequent temptation to specialize in something more profitable than psychedelics (and ample opportunities to do so). But I have no regrets about the path I have chosen to follow.

If you wish to follow the Ph.D. route, however, pure neuroscience or neuropharmacology is extremely valuable, as it is much easier politically to give psychedelics to animals or tissue cultures than it is to humans, and there is a large amount of funding available in areas indirectly applicable to the study of psychedelics, such as the pharmacology and physiology of serotonin. This sort of research builds the credibility necessary to apply for funding to study psychedelics directly. Unfortunately, much of the research done in these fields is on animals and never directly examines higher-order thought and cognition–the levels at which psychedelics engage human consciousness in the most fascinating way. And sadly, there are few academics in these fields willing to serve as mentors for students interested in psychedelics.

Experimental psychology, the study of the human mind, is also valuable, but psychonaut psychologists have given graduate-level psychology study mixed reviews. Today’s experimental psychology Ph.D. programs reportedly involve working in very restricted domains, performing tightly controlled experiments that rarely resemble real-world conditions, focus primarily on outward behavior (as opposed to studying mind), and interpreting data in ways that are inevitably constrained by how well they fit with currently accepted theories.

Clinical psychology will allow you to build the skills necessary in any multidisciplinary team researching the psychotherapeutic value of psychedelics. When psychedelics are ultimately approved as a treatment modality, a clinical psychologist will undoubtedly be part of any such treatment team. And as a clinical psychologist, you’ll be able to design clinical trials sensitive to set and setting, which are largely ignored in contemporary psychedelic research. A focus on psychedelic–psychotherapy outcome research would be an especially useful degree, and could lead to a job at MAPS. Clinical psychology graduate students report that the most prominent psychological perspective today is cognitive-behavioral, an approach more balanced between observable behavior and cognition. Less mainstream, transpersonal graduate schools such as the California Institute of Integral Studies, the Institute of Transpersonal Psychology, or the Saybrook Institute provide an alternative to the prevailing cognitive-behavioral paradigm. Collectively, these institutes are the central hubs of clinical psychology wisdom, knowledge, and experience from the sixties, largely due to the influx of faculty such as Ralph Metzner, Stanislav Grof, Richard Tarnas, Stanley Krippner, and other veterans of the psychedelic science community.

Also consider psychoanalytic training, which is not just for M.D.s anymore–learning to navigate the subconscious is a valuable skill for anyone doing psychedelic psychotherapy! A dream is not so different from a trip, and dream analysis skills translate directly. But if you’re interested in research, make sure that you get a Ph.D. rather than a Psy.D.

Cognitive science is a pure science of the mind, drawing from a variety of disciplines, including computer science. (Cognitive science was largely founded as an attempt to model and imitate the human mind on a computer system.) There are far fewer such programs than comparable psychology programs, which are ubiquitous, yet cognitive science differs from experimental psychology in that it relies strongly on theoretical and empirical work done in other fields (such as ethnographic research), especially philosophy, neuroscience, and linguistics, but also sociology, anthropology, and cultural studies. These data are then used in an integrative way to better understand and modify theoretical foundations, rather than looked at as orthogonal data from a different field. The boundaries between disciplines often dissolve, resulting in integration that is necessary in order to understand the psychedelic experience and consciousness in general.

Cognitive science, as the science of higher–order conceptual structure and thought, will permit you to broadly study the mind itself, its cognitive components, how it is manifested in neural tissue, and how meaning is created, organized, modified, and communicated by humans in the real ecological, social, and cultural environment that we inhabit. Many cognitive science programs emphasize computational modeling, which is unfortunately still in its infancy. One cognitive scientist writes:

Here, in a cognitive science program, I am able to work in labs doing both brain-imaging (fMRI) as well as electrophysiological (EEG/ ERP) brainwave research, but at the same time, study in rigorous detail theories from philosophy and linguistics while attempting to form a coherent picture of how the mind works, what thought is, and how we comprehend reality.

Ultimately, when deciding on a graduate program that will nurture your growth and refine your skills, your decision should be based on the professors under whom you will be working, the type of research that is carried out in their labs, the resources available to you, and the fit of your questions and ideas with those of your advisor. Whatever route you follow, learn as much as you can and keep your mind, eyes, and ears wide open. Absorb and integrate what you are studying with your own interests and ideas, but never shy away from something because it seems too rigid or intuitively wrong or entrenched within illusory modes of thought. Decide what you think is accurate and what is not, know why what you think is wrong is wrong, then envision a better way to understand and explain the phenomenon.

There are many paths to becoming a psychedelic researcher. Like the Internet, science views censorship as a system failure and routes around it; psychedelic research, which has long lain fallow, is slowly germinating once again. You may end up studying the biochemical and neural basis for the psychedelic experience, psychedelic psychotherapy, religious and contemplative approaches to the ecstatic experience, the nature of consciousness, law reform and public policy, going on ethnographic and anthropological expeditions, or designing and running clinical trials. You may become a strong voice in the media. But what matters most in the end is that you attain success and satisfaction on a personal, professional, and spiritual level, while at the same time remaining true to yourself and your beliefs.

So You Want to be a Psychedelic Researcher? R. Andrew Sewell, MD Answers. - MAPS

With the current renaissance in psychedelic research, after a forty-year moratorium, undergraduates interested in the topic are increasingly starting to ask: How can I get involved? Unfortunately, psychedelics are still heavily stigmatized, and...

Last edited: