mr peabody

Bluelight Crew

Psychedelic Therapy

Psychedelic drugs are known to have profound psychological effects. Now being evaluated in clinical trials in the US as aids to psychotherapy, these substances are thought to help patients by inducing spiritual experiences that lead to improved mental health. Some people challenge the claim that authentic spiritual experiences can be induced by drugs and still others question whether spirituality and religion have any place in medicine.

A hallucinogen is "any agent that causes alterations in perception, cognition, and mood as its primary psychobiological actions in the presence of an otherwise clear sensorium." The word psychedelic, which comes from the Greek to wander in the mind, and is perhaps more accurate since hallucinogenic drugs don't produce true hallucinations, rather they engender illusions that are not normally mistaken for reality, but understood as an effect of the drug. The majority of psychedelic drugs are classified as Schedule I compounds, which means that they are considered to be substances that have no accepted medical use, and have a high abuse potential.

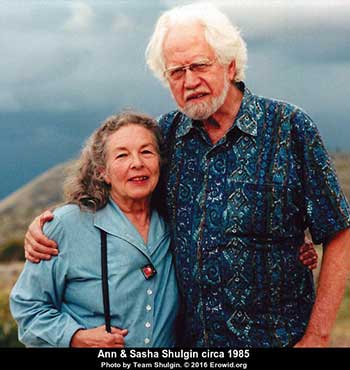

The assertion that psychedelics have no accepted medical use is a matter of contention that has been gaining a larger audience for the past couple decades. Since the first large push for the use of psychedelics in research and medicine in the 1950s and 1960s, psychedelics have largely been shunned from the medical community. Most recent evidence on the efficacy of using psychedelics in medicine has come from studies outside the U.S. or from reports of their underground use that necessarily surface to the public's attention as anecdotes. Now, however, the question of whether psychedelic drugs have any valid medical use is being revisited. More serious consideration is being given to psychedelic psychotherapy, which uses psychedelics as catalysts of transcendent experiences in order to break down psychological barriers to communication and recovery.

The director of the Drug Policy Program at UCLA, Mark Kleiman, said that there's obviously been a significant shift at the regulatory agencies and the Institutional Review Boards. There are studies [with psychedelic drugs] being approved that wouldn't have been approved 10 years ago. Part of the reason for this change is due to organizations like the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) and the Heffter Organization, which sponsor and promote studies of the medical applications of these drugs.

With at least four different FDA approved studies on the medical applications of psychedelic drugs currently being run in the US, it seems likely that our medical professionals and our society as a whole will soon have to face the ethical questions that accompany the practice of psychedelic psychotherapy. The paper will not discuss issues of legality, but will instead focus on psychedelics effects on people's spirituality as a possible mechanism for affecting their health, and on the question of the authenticity of a psychedelic-induced spiritual experience.

Psychological mechanisms of psychedelic therapy

When asked if he could see a future role for psychedelics in our Euro-American culture, Albert Hofmann responded "Absolutely! ... The pathway for this is through psychiatry, but not the psychoanalytic psychiatry of Freud and not the limited scope of modern biological psychiatry. Rather, it will occur through the new field of transpersonal psychiatry." He followed this by saying "What transpersonal psychiatry tries to give us is a recipe for gaining entrance into the spiritual world."

The idea of mixing spirituality with medicine is for most people in Western society a foreign concept, and while many people pray for a loved ones health to improve, there exists the distinction in our vernacular between healing, which is seen as more spiritual or holistic, and curing, which is accomplished through medicine. In order to understand the ethical issues behind psychedelic psychotherapy we need to have a better understanding of how psychedelic psychotherapy can affect people?s notions of meaning and the imperishable self as well as their ability to relate to other people.

Psychedelic-induced altered states of consciousness (ASCs) tend to include a certain list of common elements, one of which is a significant change in meaning and significance. Changes in meaning and significance can be found not only in how a patient views the world, but also in how they think of the content of their therapy. Two of the main protagonists of the field of transpersonal therapy were Stan Grof and Abraham Maslow, who both thought that a person could attain their optimal psychological health through altered states of consciousness. ASCs were thought to catalyze a therapeutic response, possibly by adding significance to therapy for the patient. In the report from a man who used ayahuasca, a hallucinogenic concoction made from a vine, to treat his colon cancer, the man talks about the thoughts that he had during his trip and says "when the vine reveals such things, the impact is far more profound."

Psychedelics seem to be able to amplify the significance and meaning of thoughts, or at least bring people closer to certain kinds of thought. Myron Stolaroff, cofounder of the International Foundation for Advanced Study in Menlo Park, California believes that the great value in these chemicals is that, in some way still not scientifically explained, they dissolve the boundaries to the unconscious mind, which allows one to then experience "the great relief of being in touch with all aspects of ones being. The joy and thrill of being totally alive comes from having complete access to all of ones feelings." The possibility of uncovering repressed thoughts and uniting a persons fragmented mind sounds appealing, but Vivian Rakoff, the emeritus professor of psychiatry at the university of Toronto cautions us that "every few years, something comes along that claims to be what Freud called the royal road to the unconscious." Transpersonal psychotherapy may be just another empty hope, but nevertheless, Rakoff says that research in psychedelic psychotherapy should be

allowed to continue.

Some of today's current medical studies with psychedelics that are seeking to re-examine psychedelic drugs therapeutic potential focus on their use in palliative care. Thousands of studies on the use of psychedelics in psychotherapy were published back in the 1950s and 60s before these drugs were scheduled. But many believe that these early studies do not, meet the standards of modern psychotherapy research, and that cautious reexamination of their [the psychedelics] therapeutic potential may be in order.

One such study is being run by Charles Grob, MD at the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, and another is headed by John Halpern of Harvard University McLean Hospital. Both studies are looking to validate older studies that showed how the terminally ill were able to come to decrease their pain and anxiety about death through transpersonal psychotherapy. Sherwood, Stolaroff and Harmon explain how transpersonal psychotherapy might mitigate existential ills associated with the dying process with the following:

There appears to emerge a universal central perception, apparently independent of subjects previous philosophical or theological inclinations, which plays a dominant role in the healing process...

Much of the psychotherapeutic changes are seen to occur as a process of the following kind of experience:

The individuals conviction that he is, in essence, an imperishable self rather than a destructible ego, brings about the most profound reorientation at the deeper levels of personality. He perceives illimitable worth in this essential self, and it becomes easier to accept the previously known self as an imperfect reflection of this. The many conflicts which are rooted in lack of self acceptance are cut off at the source, and the associated neurotic behavior patterns die away.

This recognition of existing as an imperishable self and not the ego that is usually dissolved or partially dismantled during the psychedelic trip is what comforts the dying. It supposedly abates their fear of death by letting them believe that their entire self will not cease to exist after death, but only their physical self.

Another perspective on the use of psychedelics by the dying comes from Joanne Lynn, president of Americans for Better Care of the Dying. She says that "even in antiquity, some groups thought is was especially important to take whatever their local psychedelic was... when confronting mortality, whether to see into the hereafter, improve spiritual growth or just numb yourself to the reality." But she followed this by saying "it's sometimes poetic, sometimes majestic, but often mundane work to wrap up one's life. I think its unlikely there's a pill that will make that go away".

A psychedelic pill might not make the mundane work of reconciling with ones family go away, but it might make it easier. Elizabeth K., psychiatrist and author of over 14 books on coping with dying believed that "simply prompting patients to express their many thoughts, feelings, and concerns would be helpful to them..."

Such discussions could address concrete problems and relieve the patient of responsibilities and burdens that prevented the patient from dying in peace. Considering the report by Eric Kast, M.D. that LSD is... capable of improving the lot of dying individuals by making them more responsive to their environment and family, one can see how psychedelics might be able to facilitate this process of prompting patients to express themselves.

If the interaction between a patient and their loved ones is important for the patients well being, then it might also be pertinent to consider the well being of the loved ones as a factor in a patient's treatment. One study that measured factors affecting the global quality of life (QoL) of both cancer patients and their spouses found meaningfulness to have highest correlation with QoL in both groups. The study concluded by calling for greater attention to the existential domain in palliative care, both when measuring and when trying to improve quality of life for these patients... This call for increased attention to existential concerns was echoed in another study that found that "patients with an enhanced sense of psycho-spiritual well-being are able to cope more effectively with the process of terminal illness and find meaning in the experience."

Conclusion

Psychedelics are powerful drugs that have great potential to help as well as harm. This paper discusses the use of psychedelics in transpersonal psychotherapy and the ethical issues that accompany their employment as medicines. After examining how these drugs are thought to work in psychotherapy and their ability to cause authentically spiritual experiences, we should be better prepared to make informed decisions about the use of these drugs that not only affect ones body, but ones mind or even soul. US law says that psychedelics have no medical application, but depending on the results of a handful of current studies this may soon change. Because, compared to many other drugs, psychedelics are relatively benign physiologically, many arguments against their use are moral, not medical, objections. And as Francis, points out: We are... unwilling to take a clear stand on drugs solely on the basis that they are bad for the soul. Whether a drug is good or bad for the soul and a person's spirituality is a tough question to ask, but that does not make it impossible to answer. The soul aside, how drugs affect consciousness is a tough question in and of itself. The psychedelic mind-state is poorly understood, but its implications for human spirituality and psychiatric health nonetheless warrant a thorough investigation, which in view of their potential benefits could even be seen as unethical not to pursue.

http://www.neip.info/downloads/brian...1_anderson.pdf

Last edited: