mr peabody

Bluelight Crew

Dr Ben Sessa

Ketamine to treat depression and addiction at UK’s first medical psychedelic psychotherapy clinic

by Charlotte Ricca | INEWS | 25 Jan 2021

Using a class B drug to help mental health problems might not sound too sensible when it is commonly known as a horse tranquilliser and possession can carry a prison sentence of up to five years. But with excitement growing at its ability to aid depression, ketamine will be one of the first treatments offered at the UK’s first medical psychedelic psychotherapy centre when it opens in spring.

Awakn Life Sciences plans to begin welcoming patients to its clinic in Bristol in March, offering “innovative approaches”. While a key concern about psychedelics is the risk of addiction, recent trials have indicated that ketamine is proving successful in helping addicts conquer their demons.

“These drugs are banned and they are illegal, but there is strong evidence that ketamine-assisted psychotherapy is both useful and safe in a wide range of psychiatric indications,” Dr Ben Sessa, Awakn’s chief medical officer, tells i.

Sessa, a clinical psychiatrist, has set up the clinic with Awakn’s chair, Professor David Nutt, who was sacked as the government’s chief drug adviser in 2009 after saying that ecstasy and LSD were less dangerous than alcohol, a claim he stands by.

Ketamine was first developed in 1962 as an anaesthetic, but growing evidence has shown its clinical value in helping treatment-resistant depression. Awakn, which is owned by a Canadian holding company, plans to broaden its use to treat anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), eating disorders and addiction.

‘A powerful combination’

‘A powerful combination’

In 2019 a government-backed study explored the combined use of psychological therapy with a low dose of ketamine, over three weeks, as a treatment for alcoholics with mild depression. The results of the Ketamine for reduction of Alcoholic Relapse (Kare) phase II trial – run by Professor Celia Morgan, a member of Awakn’s scientific advisory board – have not yet been published.

One person who took part, Grant Plant, says it “has totally reset my brain.” “I was drinking up to two bottles of wine a night, but since taking part in the trial over a year ago I have not had the urge to drink,” says Plant. “I am a complete advocate for psychedelics in the treatment of addiction.”

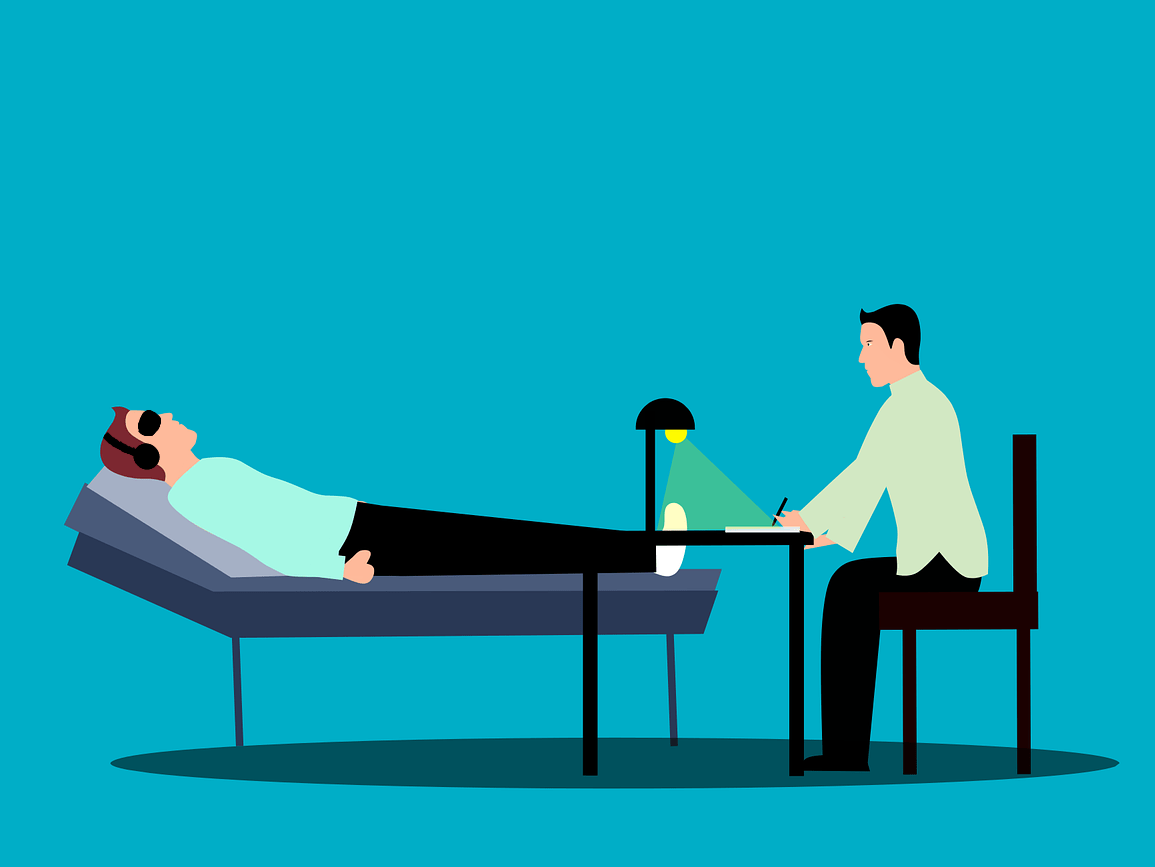

The ketamine-assisted programme at Awakn will follow a similar format. “There are other ketamine clinics, but they use the drug primarily for its pharmacological anti-depressant effects,” Sessa explains. “The key difference is we will augment the ketamine experience with psychotherapy. It’s a powerful combination, as psychedelic drugs provide deeper opportunities for patients to address and challenge their long standing rigid mental health problems.”

Psychedelics achieve their therapeutic effects through “dissociation”, which can induce feelings of disengagement from your surroundings and sense of self. This is what makes ketamine an effective anaesthetic, as it separates you from the pain, says Sessa. “It’s also incredibly safe and is routinely used in A&E, particularly on children, as it causes minimal damage to any organs and has no interaction with other drugs.”

Although ketamine is approved for anaesthesia, it has not been licensed as a recommended drug for psychiatric work, meaning for now it is being used “off label.” Sessa believes there is “every indication” this may soon change.

A ketamine-based nasal spray called esketamine, was licensed for psychiatric use in 2019 after a study that showed patients who used it had a 51 per cent lower risk of relapse. However, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has not recommended it for use on the NHS due to its high cost and “uncertainty about whether improvement in symptoms and quality of life can be sustained.”

One person who took part, Grant Plant, says it “has totally reset my brain.” “I was drinking up to two bottles of wine a night, but since taking part in the trial over a year ago I have not had the urge to drink,” says Plant. “I am a complete advocate for psychedelics in the treatment of addiction.”

The ketamine-assisted programme at Awakn will follow a similar format. “There are other ketamine clinics, but they use the drug primarily for its pharmacological anti-depressant effects,” Sessa explains. “The key difference is we will augment the ketamine experience with psychotherapy. It’s a powerful combination, as psychedelic drugs provide deeper opportunities for patients to address and challenge their long standing rigid mental health problems.”

Psychedelics achieve their therapeutic effects through “dissociation”, which can induce feelings of disengagement from your surroundings and sense of self. This is what makes ketamine an effective anaesthetic, as it separates you from the pain, says Sessa. “It’s also incredibly safe and is routinely used in A&E, particularly on children, as it causes minimal damage to any organs and has no interaction with other drugs.”

Although ketamine is approved for anaesthesia, it has not been licensed as a recommended drug for psychiatric work, meaning for now it is being used “off label.” Sessa believes there is “every indication” this may soon change.

A ketamine-based nasal spray called esketamine, was licensed for psychiatric use in 2019 after a study that showed patients who used it had a 51 per cent lower risk of relapse. However, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has not recommended it for use on the NHS due to its high cost and “uncertainty about whether improvement in symptoms and quality of life can be sustained.”

‘Psychedelic psychotherapy represents a new future’

‘Psychedelic psychotherapy represents a new future’

Professor Rupert McShane, a consultant psychiatrist at the University of Oxford, wrote in the British Medical Journal in 2019 that ketamine offered “new hope for the millions of patients worldwide who don’t respond to conventional drugs”, but added that more work is needed on dosing and the long-term safety of continued use.

“Yes, there is a lack of evidence, but this means we have to create evidence,” says Sessa. “There is a pioneering, experimental aspect to what we are doing. Sometimes this means you have to be brave and push forwards, but do so as safely as possible. It’s about assessing the risk-to-benefit ratio.”

Sessa hopes to expand the clinic’s treatments to include MDMA, commonly known as ecstasy, and Awakn’s research team has been involved in the first UK safety study into recovering alcoholics using MDMA-assisted drug therapy, led by Imperial College London.

The results have yet to be published, but Sessa says just 12 per cent of participants returned to pre-drinking levels within nine months. “Gold standard treatments, such as rehab and group therapy, see 80 per cent return to drinking at nine months, so this a staggering result which blows those other treatments out of the water,” he says.

Last year Professor Nutt called for restrictions on research into psychedelic drugs to be eased to help make new breakthroughs.

Sessa is also hopeful about psilocybin, the hallucinogen in magic mushrooms, but like MDMA it can only be used for research. Whether they will ever be licensed as a medicine – and how effective they could be – remains to be seen.

“There is no cure-all and no magic wand,” says Sessa. “Mental health is complex process of factors, but psychedelic psychotherapy represents a new future.”

Awakn will use a maximum dose of 100mg, which Sessa says is around a third the amount that would be given to a 10-year-old child in A&E. Therapy is carefully controlled, with a doctor in attendance and an experienced psychedelic therapist offering support.

inews.co.uk

inews.co.uk

“Yes, there is a lack of evidence, but this means we have to create evidence,” says Sessa. “There is a pioneering, experimental aspect to what we are doing. Sometimes this means you have to be brave and push forwards, but do so as safely as possible. It’s about assessing the risk-to-benefit ratio.”

Sessa hopes to expand the clinic’s treatments to include MDMA, commonly known as ecstasy, and Awakn’s research team has been involved in the first UK safety study into recovering alcoholics using MDMA-assisted drug therapy, led by Imperial College London.

The results have yet to be published, but Sessa says just 12 per cent of participants returned to pre-drinking levels within nine months. “Gold standard treatments, such as rehab and group therapy, see 80 per cent return to drinking at nine months, so this a staggering result which blows those other treatments out of the water,” he says.

Last year Professor Nutt called for restrictions on research into psychedelic drugs to be eased to help make new breakthroughs.

Sessa is also hopeful about psilocybin, the hallucinogen in magic mushrooms, but like MDMA it can only be used for research. Whether they will ever be licensed as a medicine – and how effective they could be – remains to be seen.

“There is no cure-all and no magic wand,” says Sessa. “Mental health is complex process of factors, but psychedelic psychotherapy represents a new future.”

Awakn will use a maximum dose of 100mg, which Sessa says is around a third the amount that would be given to a 10-year-old child in A&E. Therapy is carefully controlled, with a doctor in attendance and an experienced psychedelic therapist offering support.

Ketamine to treat depression and addiction at first medical psychedelic psychotherapy clinic

The class B drug is to be used by Awakn Life Sciences when its centre opens in Bristol in March, explains its chief medical officer Dr Ben Sessa

Last edited: