Psychedelics and Extreme Sports

by James Oroc

According to the legends of this tight-knit underground, many incredible feats having been accomplished by modern extreme-athletes while under the influence of psychedelics. LSD can increase your reflex time to lightning speed, improve your balance to the point of perfection, increase your concentration...and make you impervious to weakness or pain.

For those unfamiliar with the effects of psychedelics, the title of this article may seem like a contradiction – for what connection could there possibly be between these psychedelic compounds and extreme sports? Based on the tangled reputation that LSD has had since the mid-1960’s it would seem impossible to believe that various experienced individuals have climbed some of the hardest big walls in Yosemite, heli-skied first descents off Alaskan peaks, competed in world-class snowboarding competitions, raced motocross bikes, surfed enormous Hawaiian waves, flown hang-gliders above 18,000 feet, or climbed remote peaks in the Rockies, the Alps, the Andes, and even above 8000 meters in the Himalayas – all while under the influence of LSD.

However, in the underground culture of extreme sports, the use of LSD or psilocybin while skiing, snowboarding, mountain biking, surfing, skateboarding, etc., is in fact common throughout North American ski and sports towns, where they enjoy an almost sacred reputation. According to the legends of this tight-knit underground, many incredible feats having been accomplished by modern extreme athletes while under the influence of psychedelics.

Popular perception about the disabling effects of psychedelics and their use in the extreme sports community is mostly a matter of dosage and historical familiarity. LSD is extraordinarily potent - effective on the human physiology in the millionths of grams (mcg), and very small differences in dosage can lead to dramatically different effects. In the first decade of LSD research it was commonly accepted that the “LSD intoxication” occurred when dosing over 200mcg. At the lower dosages, a state was known as “psycholytic” was also recognized, where in may cases cognitive functioning, emotional balance, and physical stamina were actually found to be improved.

This recognition of the varying effects of LSD was lost after the popular media demonized LSD with the help of the various myths and excesses of the “1960s Love Generation.” When LSD made the jump from the clinic to the underground, its early explorers were universally fascinated with the higher dosage entheogenic experience, while the more subtle effects at lower dosages were largely forgotten or ignored. The first “street” LSD in the 1960’s was generally between 250 and 500mcg — a potency powerful enough to guarantee the casual user a truly psychedelic experience.

LSD is somewhat unusual, however, in that a user can build a fast tolerance to the compound after regular (daily use) and while one’s initial experiences on even a single dose can be dramatic, before long veteran psychonauts may be increasing their own dosage tenfold – thus requiring much stronger “hits” than the average user. It was the high dosage of this early street LSD that in combination with the complete ignorance of its early users that would be responsible for the high number of “acid casualties” that gave LSD its fearsome reputation. However, by the 1980’s both Deadheads and the rave generation had realized to drop the dosage of street LSD to between 100-125mcg, while these days a hit may be as low as 50mcg—or as little as ten percent as powerful as a hit of 1960’s LSD. Which is a dosage well below the true psychedelic threshold for most people, and for an experienced user suitably inclined, can certainly be calculated to fall within the forgotten “psycholytic” category."

There was always a strong contingent of “experienced psychedelic users” among the extreme sports community due to the little-realized fact that the seeds of the extreme sports revolution were actually planted with the dismantling and dispersal of Psychedelic Culture in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. As countless numbers of counterculture refuges left the major cities and moved out to small towns in the country in the “Back to the Land” movement, most were looking for new paths to fulfillment after the spectacular promises of the brief “Psychedelic Age” had failed and a new age of uppers and downers was emerging.

They were faced with an obviously dangerous downturn in what was now being universally called the “drug culture.” First heroin, and then, cocaine, dramatically increased in popularity, which marked the beginning of our urban society’s more than thirty year-old epidemic of cocaine and amphetamine abuse. A few turned to the traditions of Christianity, Islam, Eastern, or New Age religions, while many others, perhaps less institutionally inclined, went to small coastal towns in California, Oregon, or even Hawaii to surf. Or they landed in the numerous small towns in the Rockies from Montana to New Mexico that were being developed as ski areas at that time.

These “hippies” bought with them a newly found cultural respect for the land, which had come directly from the use of psychedelics, since the use of psychedelics in nature inevitably increases the spiritual appreciation of one’s role in nature, and of Nature itself. (There are many commentators today who believe that the modern environmental movement was born out of the fact that 25 million people took LSD in the late 1960s). They also had an adventurous attitude toward the land, derived from a general fascination with the Plains Indians and the Wild West era, and from the naturalist vision of the American wilderness that Walt Whitman, Thoreau, and especially Jack Kerouac espoused - the philosophy that one could somehow “find oneself” out among the wilds of America.

At the same time as this sudden influx of these “freaks” to the beaches, deserts, and mountains of the world, technological advances in what were considered minor cult-like sports were suddenly allowing ordinary individuals unprecedented access to the wildernesses of the world. In the mountains, the ocean, and even the air, a new kind of athlete took the concept of “finding oneself in the wilds” to a whole new definition. The invention of these highly individualistic sports (surfing, skateboarding, snowboarding, BASE jumping, tow-in surfing, etc.) that sought to use existing terrain in new and inventive ways generally raised the ire of the status quo, and so most “extreme sports” begin life as “outlaw sports” of some kind or another, with their participants regarded as rebels.

The attraction of these types of sports for the newly arrived psychedelic era refugees is obvious, and most of the leading figures of surfing, rock climbing, back country skiing, hang gliding, etc., of this era were clearly cultural rebels living well outside of the norms of society. For this particular branch of the psychedelic tree, the oceans, deserts, and great mountains of the world were now being recognized as the ultimate “set and setting” – a realization common to mystics and saddhus since the beginning of recorded time.

Thanks to the sudden exponential growth of the worldwide leisure industry towards the end of the 1970s, becoming a climbing, skiing, or surfing “bum” became the easiest way of dropping out of contemporary society, a socially healthier alternative to the free love communes of the previous decade that still allowed one to smoke pot, take psychedelics, and mostly fly under the cultural radar. By the 1980s a good portion of any American ski town (and especially the leather-booted telemark skiers) were Dead-heads, and the most effective LSD network in the country–while many other less obvious skiers and climbers still kept the tradition of using pot (a remarkable natural analgesic), LSD, and mushrooms in the mountains alive, where the mountains themselves acted as natural shields from prying eyes.

After the invention of snowboarding, mountain biking, and to a lesser extent paragliding, in the 1980s, virtually all of the newly named “extreme sports” experienced a rapid growth of popularity in the mid 1990s. This resulted in a corresponding growth in the populations of these same small ski and sports towns. Between 1992 and 1997 MTV Sports was one of the most popular shows on cable television, as it glorified the emerging “extreme-sports” to its youthful audience and established the “grunge” and hip-hop music it was promoting as the “in” sound of the now exploding snowboarder population.

"If you start asking about sporting feats accomplished on psychedelics in pretty much any bar in a ski town, you will hear some fine tales..."

The emerging electronic (rave) music of the same time period also appealed to the naturally rebellious nature of extreme athletes and introduced that culture to Burning Man from its very inception, further reinforcing the knowledge of modern psychedelic culture in what are often remote mountain towns. (“Black Rock City” got its name in 1995, the same summer as the first X Games.) Many Western ski towns now have a resident “Burner” population, much in the same way they had “hippy” or “freak” population in the early 1970s, and these small towns generally remain more liberally-minded than other towns of similar size in America.

This entwined relationship between the cultures of psychedelics and extreme sports has in fact been there since the beginning, with what is perhaps the original extreme sport, the much mythologized sport of surfing. After the fallout of 1967-68, when San Francisco and the Haight-Ashbury became overrun, and its original hipster founders abandoned it, the Southern Californian surfing town of Laguna Beach became the defacto center of the psychedelic world when a group of diehard surfers – known as the Brotherhood of Love – became the world’s first LSD cartel.

Along with the smuggling of tons of hashish from Afghanistan to fund their operation, they were responsible for distributing tens of millions of hits of Orange Sunshine LSD. In explaining the connection between LSD and surfing, early Brotherhood member Eddie Padilla remarks on the practical side of a culture based on pot and psychedelics use:

“The effect of the LSD we were taking was starting to demand a higher quality lifestyle, food-wise and in every way. All these surfer people had that lifestyle already in place. To surf, you had to remain sober and be more in tune with nature. Don’t get too screwed up, because the surf may be good tomorrow.”

In this explanation, Eddie Padilla hits on half of the real physical reason why psychedelics have always been a part of extreme sports culture, in that psychedelic use is not only more inspiring in the wilderness, but it is also eminently more practical. LSD can easily be a 10 to 14 hour experience, which is too long of a trip for most people, and especially if it is taken at night. If it is taken in the morning, however, and one has the voluminous expanses of the ocean, the deserts, or mountains of the world to roam and contemplate, then the length of an LSD trip is rarely a problem since it will also start to fade with the end of the light of the day.

If one keeps hydrated, and the LSD trip is kept within the regular biorhythms of the user to allow normal hours of sleep, then this “trip” can in truth be one of the least physically debilitating altered states experiences available, with little or no discernible “hangover” – ridiculously so when compared to the debilitating effects of cocaine or alcohol and the extreme hangover they bring. The non-addictive and nonphysically debilitating qualities of psychedelics are of course rarely touted by the popular media, but are well known among communities that are familiar with them, and the nontoxic qualities of psychedelics are half of the physical reason for their enduring appeal among extreme athletes.

The other half of this physical reason that “psychedelic drugs” are so popular with extreme athletes is due to their previously noted psycholytic effects at the correct dosages. Virtually all athletes who learn to use LSD at psycholytic dosages believe that the use of these compounds improves both their stamina and their abilities. According to the combined reports of 40 years of use by the extreme sports underground, LSD can increase your reflex time to lightning speed, improve your balance to the point of perfection, increase your concentration until you experience “tunnel vision,” and make you impervious to weakness or pain. LSD’s effects in these regards among the extreme sport community are in fact legendary, universal, and without dispute.

It is interesting to note the similarities between the recollection of these athletic feats while in this psycholytic state, and descriptions that professional athletes give of “Being in the Zone,” a mythical heightened “state” of neo-perfection where athletes report very psychedelic effects such as time slowing down and extraordinary feats of instantaneous non-thinking coordination. Athletes and normal individuals also claim the same effects in moments of heightened adrenaline – the classic fight or flight response. As LSD research returns to the mainstream in the United States, further investigation into the claims of athletes, such as the extreme sports underground, could result in a radically different perception for the variety of uses of psychedelics.

As an extreme sports athlete, journalist, and advocate since the late 1980s, and a former resident of the Rockies for over a decade, I have witnessed tales of numerous incredible feats on psychedelics in the mountains – none of which, unfortunately, I have permission to tell of here. However, after MAPS asked me to write this article earlier this year, I started asking around for other people’s stories. If you start asking about sporting feats accomplished on psychedelics in pretty much any bar in a ski town, you will here some fine tales. I heard of a hang glider flown tandem off of a mountain top under a full moon with both the pilot and passenger on magic mushrooms, of helicopter skiing in Alaska on LSD when the guide got avalanched off a cliff right in front of the tripping skier, and of radical solo rock or ice climbs of the highest intensity performed on equally radically headfulls of psychedelics. I even heard of someone taking a hit of DMT before they jumped out of an airplane skydiving. (Now that’s crazy!) I also have no doubt that someone rides Slickrock in Moab on mushrooms or LSD probably every single day, and that you couldn’t calculate the number of people who are tripping when it snows in the Rockies. Psychedelic use among extreme sports enthusiasts is simply that prevalent, and has been since the start.

Psychedelics and sports, incredibly, can go together like cheese and bread. An enhanced spiritual appreciation of the natural environment, along with increased stamina and an almost unnatural improvement in balance, are too powerful of a combination not to become sacred among mountain athletes. When I asked a well-known high-altitude climber in Colorado about climbing in the Himalayas on LSD, he just laughed and stated that at high-altitude LSD was like “cheating” since it did such a good job of overcoming fatigue and altitude sickness. He also had no doubt that someone had summited Mount Everest while tripping. But I can see how this could all seem very circumstantial and uncorroborated to someone who is skeptical, so I can offer the single documented example of LSD being used in a truly remarkable sporting achievement. This is not one that comes from the outlaw fringes of the extreme sports, but from baseball, from America’s sport itself.

On June 12th, 1970, the Pittsburgh Pirates starting pitcher, Doc Ellis, threw a no-hitter against the San Diego Padres in a regular major league baseball game, which he admits occurred while he was on LSD. Ellis had thought he was off the pitching roster for that day and so had taken LSD with friends in Los Angeles, only to find out, while high, that he had to pitch a game against the Padres that night.

As Ellis recounted it:

"I can only remember bits and pieces of the game. I was psyched. I had a feeling of euphoria. I was zeroed in on the catcher’s glove, but I didn’t hit the glove too much. I remember hitting a couple of batters and the bases were loaded two or three times. The ball was small sometimes, the ball was large sometimes, sometimes I saw the catcher, sometimes I didn’t. Sometimes I tried to stare the hitter down and throw while I was looking at him. I chewed my gum until it turned to powder. I started having a crazy idea in the fourth inning that Richard Nixon was the home plate umpire, and once I thought I was pitching a baseball to Jimi Hendrix, who to me was holding a guitar and swinging it over the plate."

So for those of you who find it hard to believe that someone can ski, mountain bike, or even fly a hangglider while on psychedelics, I submit to you the well documented case of Doc Ellis, and the fact that a no-hitter in baseball is considered one of the hardest achievements in professional sport; while there have been over 175,000 professional baseball games played since 1900, only 269 no-hitters were pitched between 1879 and 2010. Doc Ellis would go on to be in the World Series with the winning Pirates, and was the starting pitcher for the National League in the All Star Game, but this now-legendary LSD-fueled day was his only no-hitter.

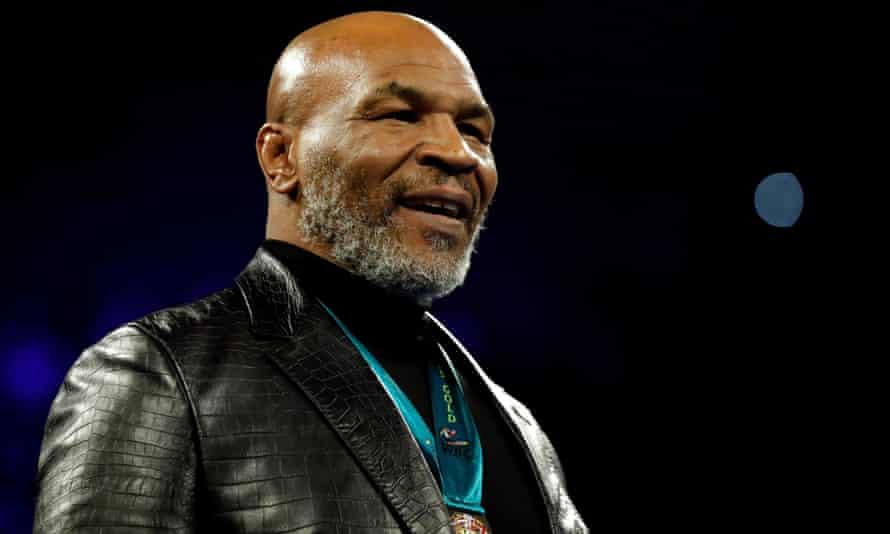

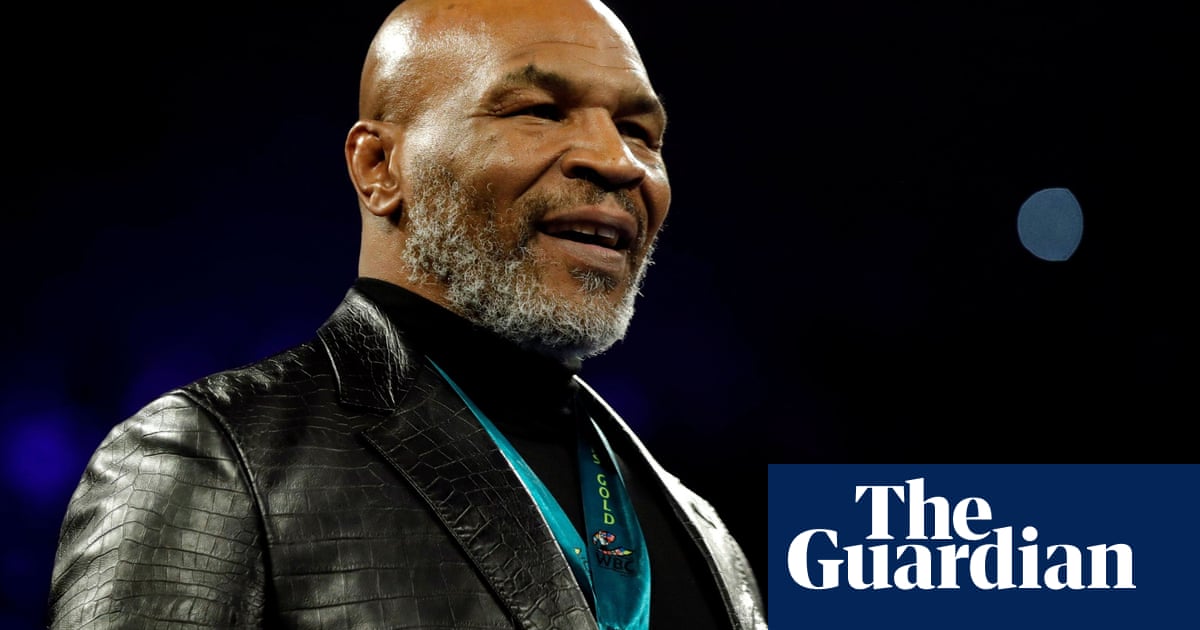

Athlete and journalist James Oroc has been involved in extreme-sport culture since 1987. In 1993 he made the first flight by a paraglider from the top of the world’s tallest active volcano, (Cotopaxi, Ecuador. The author of

Tryptamine Palace: 5-MeO-DMT and the

Sonoran Desert Toad; From Burning Man to the Akashic Field (Park Street Press, 2009), Oroc also writes and lectures regularly about entheogens and is the curator of

www.DMTsite.com, launched in 2011.

https://maps.org/news-letters/v21n1/v21n1-25to29.pdf