How I ease my OCD and anxiety with psychedelics

by Amanda Gelender | Psychedelic Exploration | 10 Mar 2020

I have struggled with OCD and anxiety for about 25 years. My OCD has shapeshifted over time, camouflaging into each phase of my life, but the themes have remained pretty consistent through the years. At this point in my life, my OCD could perhaps best be described as

primarily obsessional meaning that while I have compulsions, obsessive and intrusive thought loops are the most debilitating aspects of my condition. At times, OCD fear loops have been so overwhelming that entire parts of my life shut down - for example, I stopped driving for years because I couldn’t shake the terrifying fear that I would accidentally hurt someone.

I have been fortunate enough to work with many different healing modalities throughout my life, including talk therapy, community support networks, acupuncture, medications (

many!), cannabis, peer-support group therapy, physical movement, nature, and creative practices. I have also worked extensively with psychedelics to manage my OCD, anxiety, and depression. While I don’t seek or expect a “cure” to my mental health challenges, LSD and psychedelic mushrooms are life changing tools to work through my fears and come to peace with myself, facilitating some of the most transformational healing work of my life.

Working with psychedelics to support folks with OCD and anxiety is a topic of deep interest to me both personally and professionally: In addition to my own experiences, my work is to facilitate

legal psychedelic sessions with psilocybin mushroom truffles. I’m not a doctor or therapist, I facilitate experiences as someone with extensive experience with psychedelics and a love for creating the conditions for others to benefit from them the way I have. Many of the people who reach out for sessions experience anxiety and/or OCD, so I’m frequently in conversation with folks about whether psychedelics may be helpful tools to support them.

There are still many open questions about how and why psychedelics impact people the way they do - this is not merely a scientific inquiry, it is also political, philosophical, cultural, and spiritual. In this age of crumbling drug prohibition, western science is trying to catch up to what

indigenous people have known for centuries about the healing potential of entheogenic plant medicine. Researchers have only begun to scratch the surface on psychedelic applications for

OCD and

anxiety, but

the results so far are very promising. I’m confident that in the coming years, psychedelic medicine will become mainstream treatment for a broad range of mental and physical health challenges. We just have to keep our focus on access and

decriminalization, being wary of how these incredibly powerful tools may be

co-opted under capitalism and a for-profit medical system.

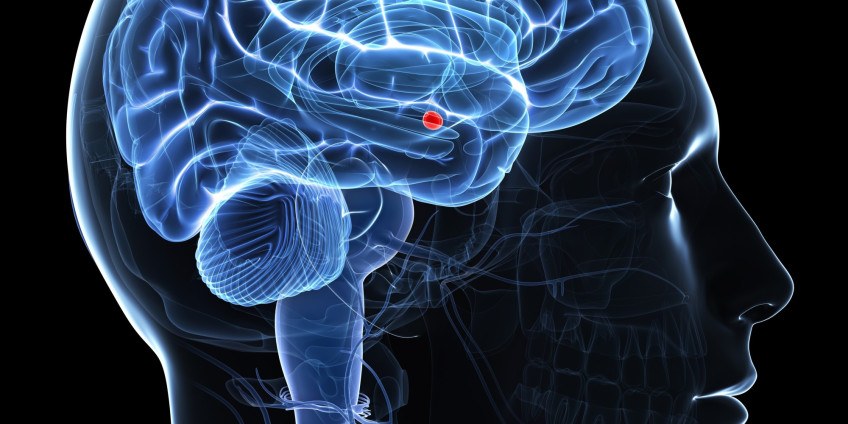

In a neurological context,

the current working theory about classic psychedelics and the brain is that it temporarily quiets down the “default mode network,” a part of the brain that filters and communicates information between various regions. So when the default mode network goes off duty during a psychedelic trip, parts of the brain can communicate that don’t usually talk to each other and new neural connections

form. We suddenly have unfiltered access to a slew of information, memories, and feelings that are often difficult to tap into in our standard state of consciousness. It can help us feel what some call “ego dissolution,” a sensation that changes

how we see ourselves, which

research has linked to the positive benefits of psychedelics. Below is

an image of brain scans depicting the neural connections with psilocybin (image b) and a placebo (image a):

But what does this mean on a practical level? Well, it’s different for everyone. I have found that in the psychedelic state it’s easier to go past the mind and work through trauma in my body. I can release control and explore my deepest fears and traumas at the root of my anxieties. I can hold myself with compassion and feel through repressed emotions, tapping into a sense of universal oneness and spiritual connection. I can feel tremendous joy, sorrow, rage, euphoria, and humility, a powerful emotional catharsis that cleans my pipes. In the time after a trip, there is often a window of

neuroplasticity that can particularly support folks with depression and anxiety - it often feels a bit easier to try new things and shake up old habits. I feel more present and aware of what I want. I feel re-energized, appreciative, and grounded. Ideas, fresh perspectives, and creativity comes more easily. My connections and community work deepens. All of these shifts help ease the daily struggle of anxiety.

Of course when we ask a question like, “How can psychedelics help relieve anxiety?” we have to remember the context in which we attempt to heal: Racialized capitalism. We live under political systems that exacerbate and facilitate trauma and perpetual anxiety, particularly for Black and Brown people. It’s very hard to heal yourself in an environment that continues to inflict harm. So we have to remember that while mental health challenges can feel like individual plights, they are often not so much personal pathologies as they are natural ways of responding to our environment. While psychedelics are incredibly powerful tools for exploration and healing, to truly address the roots of mental health crises, our focus must always be on systemic level change.

From what I have witnessed with clients, people heal differently with these tools and it can change over time. Some folks have a radical shift after a trip, others may have a more subtle shift or may not resonate with this modality at this point in their life. A trip that facilitates a strong sense of interconnectedness with the universe (ego “death” or dissolution)

can support folks who struggle with depression and anxiety. But in my experience, ego dissolution isn’t a prerequisite for substantial healing with psychedelics. I like to remind clients that the wisdom from psychedelic sessions can come in many forms: Just because there may not be a stark, immediate shift after a trip doesn’t mean that important work isn’t being done. Rather than a silver bullet, I view psychedelic sessions as powerful steps on a healing and growth path. Each trip I shed another layer and go deeper - it’s a process that can take time.

So while my work with psychedelics hasn’t eradicated my OCD or anxiety symptoms, the volume has turned down, and I have renewed mental, emotional, and spiritual fortitude to traverse challenges when they arise. A great example is my writing - OCD would want to block me from publishing this piece (“Have I checked it enough times to see if I said something incorrect? Will I accidentally cause damage with what I share?”...) but I move through the fear and publish anyway. It’s not that those voices aren’t there, it’s that they don’t drive and control my life the way they used to. In working with psychedelics through the years, I’ve become less fear-based. I feel more aligned and at peace with the natural ebb and flow of things.

I have also found that psychedelics work well in partnership with other healing modalities. People who have healing practices in place before their trip often have an easier time integrating the lessons from psychedelic journeys. By the same token, psychedelics can enhance existing practices, helping people go deeper and unlock new levels in talk therapy, meditation, and artistic expression, for instance.

Trip tips for those with OCD & anxiety

The many unknowns of a psychedelic journey can be the perfect catalyst for worry, particularly for those of us with a proclivity towards looping, catastrophizing, and worst-case scenarios. It’s completely normal to be scared before a psychedelic journey - I was certainly terrified before my first psychedelic trip and I’m so grateful to have had thorough preparation and a supportive person there with me to help me feel safe in my exploration.

A wide range of experiences are possible in a psychedelic journey and even healing trips can sometimes feel scary or even traumatic. In my experience, going through these dark places in psychedelic journeying can still bring great positivity, but only if the container around the trip is supportive. This is

supported by research which found that the majority of people who have had challenging psychedelic mushroom experiences still said they were “‘meaningful’ or ‘worthwhile,’ with half of these positive responses claiming it as one of the

most valuable experiences in their life.”

To set yourself up for a safe and transformational session, it’s always wise to follow basic prep guidelines - access the medicine from a trusted and safe source (testing the substance if necessary), know a good starting dose,

check how medications may affect your trip, prepare and feel as centered as possible before the journey (set), arrange for a safe and nourishing space (setting), have a person with you for support (sitter or guide), and allot time to process in the days following the session (integration).

I actually think that a healthy mix of nervousness and excitement before a trip is a good thing: It demonstrates that you have reverence for how powerful a psychedelic teacher is and that it has the potential to significantly shift your life. But of course it’s best not to go into a trip feeling too anxious, so practice grounding yourself before the journey. And if you’re really struggling the days leading up to the trip - don’t push it. Check in with yourself and see if you want to postpone your trip or start with a lower dose.

It’s also important to note that psychedelics aren’t for everyone and it can shift depending on what you’re going through. For instance, I don’t go on full dose trips when I am in a depressive crisis, a particularly bad OCD episode, or when I’m very stressed or overworked. I’ve found that these trips can be unnecessarily challenging or even temporarily damaging, so I wait until I feel a bit more stable to have a session.

After your trip, be kind to yourself and take time to process in whatever ways feel most natural to you. It can be particularly helpful to write, draw, rest, and be in nature in the days following your journey. It’s normal to feel many things after a trip so let the changes unfold over time and don’t rush to make sense of everything. Be patient if changes don’t come right away and remember that for those of us who struggle with anxiety and OCD, just the act of releasing control and taking the leap into the psychedelic journey is a huge achievement.

By Amanda Gelender

psychedelicexploration.com