Ketamine Therapy is going mainstream. Are we ready?

The mind-altering drug has been shown to help people suffering from anxiety and depression. But how it helps, who it will serve, and who will profit are open questions.

by

Emily Witt | The New Yorker | 29 Dec 2021

In the fall of 1972, a psychiatrist named Salvador Roquet travelled from his home in Mexico City to the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, an institution largely funded by the United States government, to give a presentation on an ongoing experiment. For several years, Roquet had been running a series of group-therapy sessions: over the course of eight or nine hours, his staff would administer psilocybin mushrooms, morning-glory seeds, peyote cacti, and the herb datura to small groups of patients. He would then orchestrate what he called a “sensory overload show,” with lights, sounds, and images from violent or erotic movies. The idea was to push the patients through an extreme experience to a psycho-spiritual rebirth. One of the participants, an American psychology professor, described the session as a “descent into hell.” But Roquet wanted to give his patients smooth landings, and so, eventually, he added a common hospital anesthetic called ketamine hydrochloride. He found that, given as the other drugs were wearing off, it alleviated the anxiety brought on by these punishing ordeals.

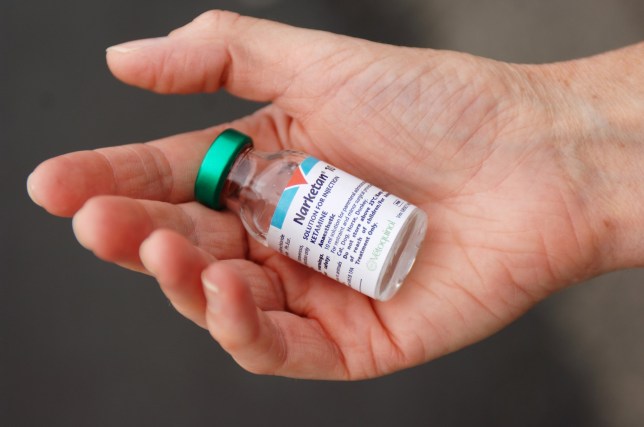

Clinicians at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center had been studying LSD and other psychedelics since the early nineteen-fifties, beginning at a related institution, the Spring Grove Hospital Center. But ketamine was new: it was first synthesized in 1962, by a researcher named Calvin Stevens, who did consulting work for the pharmaceutical company Parke-Davis. (Stevens had been looking for a less volatile alternative to phencyclidine, better known as PCP.) Two years later, a doctor named Edward Domino conducted the first human trials of ketamine, with men incarcerated at Jackson State Prison, in Michigan, serving as his subjects. At higher doses, Domino noticed, ketamine knocked people out, but at lower ones it produced odd psychoactive effects on otherwise lucid patients. Parke-Davis wanted to avoid characterizing the drug as psychedelic, and Domino’s wife suggested the term “dissociative anesthetic” to describe the way it seemed to separate the mind from the body even as the mind retained consciousness. The F.D.A. approved ketamine as an anesthetic in 1970, and Parke-Davis began marketing it under the brand name Ketalar. It was widely used by the U.S. military during the Vietnam War, and remains a standard anesthetic in emergency rooms around the world.

Roquet found other uses for it. After his lecture in Maryland, he offered experiential training to the clinicians there.

“I was introduced to the strangest psychoactive substance I have ever experienced in the 50 years of my consciousness research,” the psychiatrist Stanislav Grof recalls in “

The Ketamine Papers,” a book edited by the psychiatrist Phil Wolfson and the researcher Glenn Hartelius. Grof subsequently experimented with ketamine personally, and found himself inhabiting the perspectives of a wet towel hanging on a railing overlooking the ocean, petroleum filling the cavities of the earth, and the prisms of a diamond.

“In one of my ketamine sessions, I became a tadpole undergoing a metamorphosis into a frog, and in another one, a giant silverback gorilla claiming his territory,” Grof writes.

When the training took place, psychedelic research was already coming under legal threat. In 1968, the U.S. government outlawed possession of LSD; Richard Nixon announced a war on drugs three years later. In 1974, Roquet was jailed for several months in Mexico, and subsequently cut back on his group sessions. (He died in 1995.) The Maryland Psychiatric Research Center ended its psychedelic research in the mid-seventies, amid broader upheaval at the center.

But ketamine remained medically legal, and countercultural psychiatrists continued to experiment with it. In the eighties, the drug’s best-known enthusiast was John C. Lilly, a doctor and psychoanalyst perhaps most famous for using sensory-deprivation tanks and dabbling in human-dolphin communication. Lilly became addicted to ketamine: a researcher who crossed paths with him at the Esalen Institute, a retreat in Northern California, recalled Lilly spending most of his time in his Volkswagen minibus, where he was evidently injecting himself multiple times a day. (Lilly said that he stopped using the drug in his early sixties, on the orders of extraterrestrials, but he resumed taking it later in life. He died in 2001, at eighty-six.) During these years, ketamine also became a popular dance-floor drug. Partyers generally snorted it, at lower doses, for a less drastic and more interactive high, experiencing distortions of perception that have been described as “scenery slicing” and “environmental cubism.” Among clubgoers, taking so much that you became unaware of your surroundings—experiencing a “K-hole”—was typically considered a scary mistake. The drug became especially fashionable among ravers in the nineties, and, at the end of that decade, the U.S. government made ketamine a Schedule III substance, putting it on the same regulatory footing as steroids and Tylenol with codeine.

Meanwhile, clinicians at Yale, who were using the drug to mimic the symptoms of schizophrenia, noticed that ketamine improved people’s moods. Researchers began studying it as a treatment for depression, and, in 2006, the National Institute of Mental Health concluded that a single intravenous dose of ketamine had rapid antidepressant effects. Around three hundred clinical trials have since been held; the broad consensus is that ketamine relieves symptoms of depression for a period that can last days or weeks, during which time talk therapy often proves more effective than normal. Ketamine is what’s called a “dirty drug,” meaning that it acts on different parts of the brain at once, and there are several theories about how it works against depression, but most focus on its effects on certain receptors in the brain, and on the neurotransmitter glutamate. (One theory holds that ketamine modulates levels of a protein that can generate new neurons.) By 2010, doctors were recommending its off-label use to acutely suicidal patients, and ketamine clinics began opening around the country. These days, the research and debate surrounding ketamine are less concerned with whether it can treat depression than with how it works, which delivery method makes it most effective, and how drug companies and health-care providers might best profit off a substance whose patent expired in the nineteen-eighties.

One of the first clinics, New York Ketamine Infusions, was opened by Glen Brooks, a Harvard-trained anesthesiologist, in 2012. Brooks sometimes wears a white lab coat, and practices in an ordinary-looking doctor’s office, where he keeps jars of FireBall candies on his desk. (He used to sublet space from a podiatrist.) He’d been a physician for more than thirty years when a relative’s drug problems prompted him to pursue addiction medicine. After just a few months, he concluded that the field was hopeless when it came to addressing the childhood traumas that lead people to self-medicate. He read the early research on ketamine as a treatment for mood disorders and saw not only reason for optimism but a business opportunity.

Brooks administers ketamine by I.V., at subanesthetic doses, and only some of his patients have dissociative experiences.

“There’s nothing therapeutic going on when they’re here,” he told me, when I visited him at his clinic on a rainy Sunday this past spring. Patients hooked up to I.V. drips were undergoing treatment in dimly lit rooms.

“We’re growing dendrites and synapses,” he said. Brooks encourages his patients to bring a friend or listen to a podcast to distract themselves from ketamine’s psychoactive effects. He said that what patients happen to think about during their sessions doesn’t really matter.

This approach, which is typical of the early ketamine clinics, contrasts with the countercultural attitude that prevailed among the drug’s advocates in the seventies and in a new tide of startups. Beginning roughly with the publication of “

How to Change Your Mind,” a best-selling book by Michael Pollan, in 2018, psychedelic treatments for mental health have gone mainstream. Publicly traded companies, such as Compass Pathways and MindMed, have begun patenting variations on psychedelic treatments. Last fall, Peter Thiel was among the investors in a hundred-and-twenty-five-million-dollar round of funding for the biotech company atai Life Sciences, which principally focuses on the use of psychedelics in the treatment of mental illness; in June, the company went public, and was valued at more than three billion dollars.

In recent years, I have watched many people in my life quit antidepressants and start microdosing LSD and mushrooms, informed by exuberant news reports and the encouraging but not yet conclusive data documented in Pollan’s book and elsewhere. Most of these people are skeptical of the pharmaceutical industry and desperate to find more pleasure in life; for some, coding substance use as an antidepressant routine, and ingesting very tiny doses, seems to suit a sense of middle-class propriety and upwardly mobile productivity. (The doctors I spoke with by and large agreed that ketamine—which a number of outlets have

proclaimed the “It Drug” of personal use during the pandemic—does not have the same clinically proven antidepressant effects when snorted.)

It is also, unlike LSD and mushrooms, legal for medical use throughout the U.S., and so provides the only avenue for American medical providers to generate revenue with psychedelic substances. (In 2019, the F.D.A. approved Spravato, from Johnson & Johnson, which contains one of the two molecules in the original ketamine formulation, and which will allow the company to sell a more profitable, if not necessarily more effective, version of the drug.) Today, a self-referring depressive with several hundred dollars on hand who is not in the throes of active mania or psychosis can seek out a wide array of clinical treatments with the drug: a titrated dose given intravenously by an anesthesiologist at a retail clinic, a shot in the arm from a psychiatrist in private practice, an oral lozenge sent in the mail by a startup taking advantage of pandemic-era changes to the regulation of remote prescriptions. If you can get to the right city, and have sufficient funds, you can easily secure a legal, therapist-guided, mind-expanding trip at a clinic that advertises on Facebook and is funded by venture capital.

The New York office of Field Trip Health, which opened in August, 2020, is situated in the Kips Bay neighborhood of Manhattan. It occupies the entire eleventh floor of a building next to Baruch College, and has big windows and a wraparound terrace. The decorative touches are spa-like: white rugs, fiddle-leaf figs, electric candles inside glass-paned lanterns. The aesthetic seems based on the assumption that, when a company hopes to take a formerly taboo practice mainstream, a West Elm interior can go a long way.

When I visited, this past spring, Matt Emmer, Field Trip’s vice president of health-care practice, showed me around—he was wearing a floral button-down of the sort that I associate with tech-company business casual. Field Trip was founded, in April, 2019, by five Canadian entrepreneurs, four of whom previously founded a chain of cannabis-dispensing medical clinics. The company now operates ten ketamine clinics in Canada and the U.S., with plans to open several more in the near future. (Field Trip recently opened a clinic in Amsterdam that offers patients guided-therapy sessions with magic mushrooms.) The company has a research and development wing, Field Trip Discovery, which is devoted to the cultivation of psilocybin mushrooms and the development of psychedelic-inspired medicines; this work is being done at a laboratory at the University of the West Indies, in Mona, Jamaica, where the drug laws are relatively forgiving. Field Trip recently filed a patent for a molecule called FT-104, which, according to preclinical experiments, targets the same serotonin receptor as psilocybin, but has much briefer effects. A drug trip that lasts two hours offers a far more viable business model than one that lasts five or six.

Emmer walked me down a hallway where the sound of water burbled from a white-noise machine, and he told me that he took interior-design cues from nature (“something that’s universal”). In the reception area, I saw copies of “How to Change Your Mind” for sale alongside “

Be Here Now,” by the psychedelic guru Ram Dass. But, for the most part, signs of the counterculture were muted. Emmer led me into a windowless room. On one wall was a mural of spider monkeys peeking through palm fronds. In a corner, there was a large, white leather, zero-gravity chair. I sat down, and, at Emmer’s invitation, pressed a button on a remote. The chair made a soothing hum and slowly tipped backward, ready to carry me across the threshold of consciousness in its arms.

“It makes you feel as weightless as possible without going into space,” Emmer said.

Sitting where the therapist normally would, Emmer explained the process. A patient arrives and selects from a menu of guided meditations and light therapy as a way of easing in before her trip. Ketamine is then administered with one or two intramuscular shots—the mind-altering equivalent of a rocket launch. The patient puts on noise-cancelling headphones, a weighted blanket, and an eye mask, and turns inward, listening to a soundtrack of nonverbal music. (One playlist is mostly classical and another is electronic; the music is intentionally obscure, to avoid provoking personal associations.)

I pressed another button on the remote, and Emmer waited as my chair slowly returned to its upright position. After the ketamine subsides, he explained, the patient sits for a session of talk therapy. The entire round of treatment lasts between two and three hours. A lounge stocked with mandala coloring books and watercolors offers a restful place to come back to earth before going home. Like most ketamine clinics, Field Trip encourages an initial set of four to six infusions spaced out across two to four weeks, with boosters available on an as-needed basis thereafter. The first session costs seven hundred and fifty dollars and subsequent treatments cost a thousand. The patient is paying for the therapy more than the drug, which costs as little as seven dollars a dose.

Earlier this year, a thirty-five-year-old filmmaker I know signed up for ketamine-assisted therapy at Field Trip. She had been reading about psychedelics during the pandemic. She read the Pollan book and a memoir called “

The Wild Kindness: A Psilocybin Odyssey.” She listened to a lot of podcasts. She had tried LSD and mushrooms before. On those trips, she felt expansive and connected to the cosmos; she looked at the clouds, which seemed to be moving backward, and at the moon, which appeared more three-dimensional than usual. She wanted to undergo other shifts in her perspective. She was experiencing a degree of anxiety and obsessive thinking—she takes antidepressants and has more than a decade of therapy in her past—but she did not believe that she had any urgent mental-health issues.

“I’m actually in a good place in my life right now,” she told me,

“and it’s more about wanting to take it to the next level.” She contacted an underground therapist about a supervised mushroom trip, but the waitlist was two years long.

“This was the path of least resistance,” she explained to me, of Field Trip.

“I literally typed something into Google.” She underwent two screenings with the clinic, the first of which focussed on what ketamine is and what it can offer, and the second of which, she told me, was “about making sure you’re not crazy or you’re not going to kill yourself afterward.”

Her first session was scheduled for June. I spoke to her later that week. The experience had been more intense than what she was expecting. Her intake sessions were conducted virtually, so the day of her trip was her first visit to the office. An employee showed her a chair with a kind of helmet that descends upon the sitter’s head and provides a choice of colored lights to set the mood for meditation. She saw a glass table with a tray underneath it, in which a self-propelled metal ball traced patterns in sand.

“I felt like I was already tripping when I went in there,” she told me. She found the burbling water sounds from the white-noise machine unnerving.

They put her in a room with a jungle-themed mural at the end of a long hall. She lay down in the anti-gravity chair and waited for its slow, dental-office recline. A nurse took her blood pressure and then presented a syringe of ketamine in a bronze Tibetan bowl.

“I had to stop myself from cracking up,” she said,

“because I didn’t want to be laughing at them, but there was something about it that was so absurd.” After the shot, she put on her eye mask and waited. She thought of her poodle at home and told the therapist that she was worried about her, but she calmed down after remembering that her partner was coming home early from work that day and would take care of the dog. She was given a second shot, and images began rushing through her mind: indecipherable hieroglyphics, ancient calligraphy. She saw herself onstage at a Q. & A. for one of her films. She experienced a kind of consciousness without identity. She felt as if she were inside a cardboard box with only a small hole of light and she was tearing at the aperture to widen it. She lifted her eye mask and looked down at her hands, and thought, Oh, wow, I’m a human. But she couldn’t remember where or who she was. Then she was overwhelmed with nausea, which happens to a modest subset of people who inject ketamine. She cancelled her second session immediately afterward.

“I still feel so out of sorts,” she told me.

But, a few weeks later, she was ready to return. At her second session, she received a lower dose, and the effects of the drug were milder. She saw a sea of waving Japanese

maneki-neko cat figurines and tried to find her mother’s face among them. A day or two later, she began to have a recurring feeling that seemed new.

“This new feeling was, What if it works out?” she told me. It was a hopeful, expansive feeling. Then, one day, it was gone.

“I guess it’s worn off or something?” she said.

“It’s funny how it’s something you can’t talk yourself into feeling.”

For the countercultural therapists who have been administering ketamine to their patients for years, the current boom is seen with bemusement and not a small amount of worry. Phil Wolfson, who co-edited “The Ketamine Papers,” first took ketamine in 1990, and began giving it to select patients twenty years later. (Prior to that, he had used MDMA in therapy, but stopped when the drug became a Schedule I substance, in 1985.) Now in his seventies, he has trained many psychotherapists in the use of ketamine, including several at Field Trip Health. In his own practice, he offers both psychotherapy with lozenges and more intense guided trips with intramuscular injections. He is fluent in the neuroscientific theories about how ketamine works but regards them as reductionist.

“Everything causes neuroplasticity,” he told me.

“Having great love, or climbing a mountain, or having a terrible tragedy—it all creates movement of dendrites”—the branched tips where neurons form pathways—

“because movement of dendrites is an essential adaptive function. We change because of experience.” We were speaking on the day after the anniversary of Wolfson’s son’s death, more than thirty years ago, from leukemia, at the age of sixteen, which Wolfson honors each year with a memorial.

Wolfson, who has a corona of silver hair and whose New York accent has resisted decades of living in California, is not eager to categorize ketamine as an antidepressant. Change is not merely a chemical by-product, he told me, and diagnostic categories help only up to a point. He believes that ketamine’s particular power is in the way that it offers a “subjective time-out.” Unlike ayahuasca or mushrooms, which often produce visions that coalesce into narratives, ketamine usually gives a brief experience of the void.

“Ketamine really makes no sense,” he said.

“It’s not attached to subjective experiences—themes don’t occur, or, if they do, they might not be particularly psychological in nature. I’m not reformed by neuroplasticity; I’m reformed by having had a break from the obsessions of my mind.”

The most striking results from ketamine therapy do not involve people like my filmmaker friend, who has manageable anxiety, but those who are experiencing chronic, treatment-resistant depression. Zachary Rice, a twenty-eight-year-old TV writer, has seen a therapist since he was ten. At sixteen, he was diagnosed with clinical depression, and in his early twenties he was diagnosed with acute post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. He began taking antidepressants at eighteen; since then, he has been prescribed thirteen different medications and has attempted suicide. In March, 2020, as the pandemic started to spread, he became suicidal again. He spoke with his therapist and psychiatrist on the phone. Concerned that more medication wouldn’t help him quickly enough, they gave him two options: hospitalization or ketamine.

“I basically only knew it as a gay party drug or a horse tranquilizer,” he said.

That call was on a Friday. The following Monday, Rice went to a clinic in Brooklyn Heights called Ember Health. Ember was started by an emergency-medicine physician named Nico Grundmann and his wife, Tiffany Franke, a strategy consultant, in 2018. Ember makes no reference to psychedelic experiences in its marketing materials, and, in conversation, Grundmann seemed wary of the term “psychedelic,” saying that it could scare some patients away. But the altered state of mind produced by ketamine is a fundamental aspect of the company’s approach to treatment, he said. The company’s office has rugs and sofas and herbal teas—

“like a well-appointed home,” he told me. He said that Ember tries to take the most evidence-based approach, which is to administer ketamine by I.V. infusion, not intramuscular injection, at a dose of 0.5 to one milligram per kilogram of a patient’s weight. Ember does not offer psychotherapy in-house, but the company only accepts clients who are actively being treated by mental-health professionals.

Rice had never taken psychedelic drugs before—he’d always worried about how they would interact with his medications. On the intake questionnaire, he got a perfect score: severe depression. He recalls thinking,

“If this doesn’t work, at least I get to try a cool drug and I know I won’t die, because I’m in a doctor’s office.”

Rice put on an eye mask and a pair of headphones and was hooked to an I.V. drip and a cardiac monitor. He was encouraged to think about a happy moment, so he thought of standing on the outer rim of Yosemite Valley and watching the sunset with his friends.

“Then it was as if the lights dimmed in a movie theatre and reality went away,” he recalled.

“I flew across the valley at five thousand miles an hour and smashed into Half Dome, then Half Dome exploded into the universe and I was floating in space.” A narrator coalesced, a kind of entity or guide, with a commanding yet comforting voice. (He sounded like Danny Glover, Rice said.) He asked Rice if he wanted to take a tour of his own brain. Rice proceeded to greet all the people who work in his brain, and then the tour moved on to the formative experiences in his life, including deeply traumatic ones that he considers the roots of his mental illness. He saw a mosaic of every person who loves him and has been important to him.

“You don’t have to scare them anymore,” the narrator said.

“You can be alive and it’s O.K. and it’s good.” It was the first time in twenty years, Rice said, that he’d had anything like a positive internal monologue. The tour concluded with an “interdimensional safari” where he watched elephants twirl until the safari car folded back onto itself and his brain merged with the driver’s. When Rice regained normal consciousness, he was laughing and crying.

He was given tea and wrote down what he’d seen. Then he took the elevator back down to the streets of Brooklyn. Outside, everyone was wearing masks, and a pigeon pooped on him. He walked into a park and looked at the birds, crying at their beauty. He went home and did chores he had put off for years.

“It was literally like entering life for the first time,” he told me, comparing it to the process of color correction when making a film.

“Ketamine color-corrected for my existence. I saw the world as it was, without this heavy gray mass.”

Rice did four sessions across ten days, and he has done monthly sessions ever since. Each session is distinct: sometimes, he gets no visions at all, and sometimes he feels like he is in a Windows 95 screensaver.

“I’ve died in ketamine sessions,” he said.

“I’ve met what I was meant to understand was God.” The sessions are five hundred dollars each, but sixty per cent of the cost is covered by his insurance. He can tell that the effect of a session is wearing off when daily tasks start to feel insurmountable, he said.

“It’s not hyperbolic to say that ketamine saved my life,” he said.

“That hour session was more transformative for my mental health than anything I’ve done in my twenty-plus years of therapy and medication.”

Field Trip, in contrast to Ember Health and New York Ketamine Infusions, seems to be interested in a broader customer base than those who are treatment-resistant. Ben Medrano, the New York clinic’s medical director, told me that he first tried ketamine and other psychedelic drugs as a raver in the nineteen-nineties, and that the spiritual benefits of such experiences should be extended to people who are uncomfortable sourcing drugs illicitly but could use a break from their ordinary mind. These benefits will never be easily verifiable in a laboratory or a double-blind study, he told me.

“These are healing tools that access the potential of consciousness,” he said.

“And, at the end of the day, we, as scientists, can’t talk about that much, because what do we say? We don’t even know where consciousness resides.”

If going to the doctor for a guided trip becomes as routine, for some, as getting Botox, there will surely be a bifurcated clinical scene: one for people who like hippie stuff and one for people who want nothing to do with it. In late June, I drove to the Catskills to watch a group of people receive training in ketamine-assisted psychotherapy at the Menla Institute, a Buddhist retreat center. There were a number of psychotherapists, but the group also included an E.R. physician, a military veteran who works to bring psychedelic-assisted therapy to fellow-veterans who have P.T.S.D., and an executive with a Miami-based startup called Nue Life.

Also in attendance was the psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk, whose book “

The Body Keeps the Score,” first published in 2014, frequently ranks among the ten best-selling books on Amazon. Van der Kolk told me about his experience working on the first studies of Prozac and Zoloft as treatments for P.T.S.D.

“They weren’t bad,” he said, but they didn’t cure anyone, he noted, adding,

“All you get now is drugs that by and large don’t work.” Van der Kolk had received an injection of ketamine from Wolfson a few years before.

“I was blown into the universe,” he told me.

“I had no mental experience—I lost my body, I lost my mind.” He emerged from his trip skeptical that ketamine could do anything, but his wife and collaborator, Licia Sky, noticed changes in him afterward.

“Before, there was like this undercurrent of impatience, like this readiness to be agitated,” Sky, who was also at the training, told me.

“That agitation got very quiet, but your power stayed,” she went on, turning to her husband.

“That doesn’t mean that we don’t disagree about things. It means that there’s a level of urgency that’s gone.”

It was an exquisite day in Ulster County. The sky was a bright blue and the mountains were a lush and vivid green. The trainees gathered in a large, wood-beamed room, at the front of which stood a shimmering gong, flanked by a trio of Tibetan wall hangings. Wolfson had set up a small altar to one side, with a framed photograph of his son. It was the fourth day of the training. Half the workshop’s participants would be receiving injections, and the other half would watch over them. On the walls, large pieces of paper bore descriptions of the previous day’s trips. Among the phrases people had written down were “breath of God” and “saw ancestral stuff.” In a corner of the room, a woman prepared for her journey with some yoga asanas. Others filtered in from a vegetarian breakfast in the retreat center’s dining hall and settled onto mats and pillows laid out on the floor.

The session began with an invocation and the recitation of a poem by Rumi. An assistant brought out paper coffee cups labelled with the participants’ names: each contained a syringe with a dose of ketamine. For the next hour, I watched the therapists undergo their training. The trip sitters monitored them closely, occasionally taking notes or mirroring their movements. A sort of drumming-and-didgeridoo song played over speakers, followed by a track that prominently featured a rainstick. The woman who had been doing yoga flung her arms out wide and moved her body ecstatically. Toward the back of the room, a man began to sob, and an assistant came to Wolfson for advice.

“We need to help him listen to the music,” Wolfson whispered.

After an hour, the group began to emerge from their trips. Wolfson took the microphone.

“Relax into your being,” he said.

“Find great peace, find your heart for yourself, find great compassion.” Assistants circulated with a tray of orange slices and the group began sharing what they had experienced. It was “not so much a seeing journey as a feeling journey,” one said. Another said that his experience in a prior session, with a lower dosage of orally ingested ketamine, had felt more beneficial—on the higher, intramuscular dose, he had gone to

“fractal land, to the matrix, and being that far out you don’t do the work,” he said. A third person said,

“Our inner children who are bereft long to be safe with their tears.” Van der Kolk, who had taken a moderate dose, of sixty milligrams, had been enamored with the soundtrack.

“Every sound becomes a vision, every sound becomes a shape,” he said. Someone else said,

“Well, what this weekend has done has given me a real appreciation of trance music.” The trainees then had lunch and attended a seminar about attachment theory.

I like hippie stuff, so when I decided to take a guided ketamine trip, I did so with Wolfson. Prior to my appointment, I completed questionnaires that evaluated my family history and whether I had experienced violence, trauma, or depression. In mid-June, I went to the lower Manhattan office of Gita Vaid, a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst in private practice who had also been at the training in the Catskills. There, Wolfson, Vaid, and I talked for an hour. I told them that I was struggling to recover from a bad experience the year before. I had taken some time off work, gone to therapy, and gone back on antidepressants for the first time in almost a decade, but I seemed unable to regain stability, or the sense of belonging that had once held me in the world. Then, Wolfson, drawing on our conversation, recited a personalized invocation to send me on my way. I lay down on a couch and Vaid put an injection in my arm.

My mind dissolved into a muted silence, as though I were in a warm, carpeted soundbooth. I had taken an initial dose of thirty-five milligrams, and no specific visions coalesced, but the soundbooth walls began to collapse, like the C.G.I. sand in “The Mummy,” and swirled into shifting shapes, blown around by gusts of a mysterious wind. It was like being immersed in a world of iron filings, drawn into patterns by a magnet in a dimly lit forge. Twelve minutes after the first shot, I was asked if I wanted the second injection, also of thirty-five milligrams. The question seemed to come from very far away, and I was surprised that I could articulate a response. Vaid lifted my sleeve and gave me another shot. Now, I was in a velvet painting; I was sinking into the carpet; I was under the canopy of a primeval forest, on its mossy floor, hidden under ferns. I wanted to sink deeper into the primordial nothing, but, in time, I became aware of my body again. Before taking the shot, I had been sad and worried. I emerged feeling calm and soothed. As psychoactive experiences go, it was five stars, truly enjoyable. All I could repeat, stupidly, as I regained awareness of my surroundings, was how “cool” it had been.

I’d done ketamine at parties before, and liked how it fragmented sensory input and seemed to dilate time; the experience of injecting it was far more intense. It was as if I had taken a different drug altogether. During the previous year, I had become increasingly skeptical of the enthusiasm for psychedelic drugs as a revolution for mental health. This may have involved some mild hypocrisy, since I have done psychedelics and have found that, in addition to being fun, they sometimes helped me gain perspective and process difficult experiences. I was uneasy about pinning messianic potential on any particular mind-altering thing, and I felt aware of the limits of what such substances could do. I also feared the warping effects of the profit motive. As I researched this article, I began getting Facebook ads for a

controversial company called Mindbloom, which sends ketamine lozenges in the mail to be taken between scheduled video sessions with a trained guide. The ads include a quote from someone saying, of ketamine treatment,

“Before I started, I felt like I had run up against a wall in therapy.”

Wolfson, the first time we spoke, told me,

“There’s this huge population of chronically depressed people in a chronically depressing world that’s making more chronic depression.” In other words, the way we live is making us sick. The suicide rate in the U.S. has increased by nearly thirty per cent since 1999; from April 2020 to April 2021, a hundred thousand Americans have died of drug overdoses, many of them presumably medicating themselves out of the difficulties of ordinary consciousness. In “The Ketamine Papers,” Wolfson offers

“a very partial list of antidepressants.” On his list: “anticonvulsants, stimulants, marijuana, exercise, meditation, hedonism, temporary satisfaction of cravings, elimination of cravings, oxytocin, sexuality, spiritual practice, money, love, children, activism, justice, a good job, respect, friendship, education, a good book, a bad book, and so on.”

Ketamine is generally considered safe when used at sufficient intervals, but, when snorted or injected daily for long periods of time, it can cause increased tolerance, cravings, withdrawal, and permanent urinary-tract and kidney damage. It may also affect long- and short-term memory.

“You do see these sort of unique personalities that are inclined to it,” Ben Medrano, of Field Trip Health, told me, of the risks of ketamine addiction.

“Like, John C. Lilly was an astrophysicist who studied dolphins.” But Medrano was insistent that it’s only “a subset of people who are prone to it.” The government classifies ketamine’s abuse potential as moderate to low. Still, the risk of overuse has long been acknowledged in underground circles. In “

The Essential Psychedelic Guide,” published in 1994, the researcher D. M. Turner writes,

“A fairly large percentage of those who try Ketamine will consume it non-stop until their supply is exhausted. I’ve seen this in friends I’ve known for many years who are regular psychedelic users and have never before had problems controlling their drug consumption.” Turner died in a bathtub on New Year’s Eve in 1996, apparently having drowned after injecting himself with ketamine.

Multiple doctors who conduct ketamine therapy assured me that they do not accept patients who are exhibiting drug-seeking behavior, and also told me that, at the pace of treatment practiced by responsible clinicians, there is minimal risk of dependency or of the urinary-tract infection known as ulcerative cystitis. But the pandemic had brought home to me some indelible lessons about the fragility of the mind. Wolfson was more willing than most of the physicians I met to acknowledge this fragility.

“Anyone doing this work as a therapist will come across those folks who become too attached to a drug or drugs, who make broad mistakes, lose their relationships, even themselves,” he once wrote, in a consideration of Lilly, the ketamine user who lost his way. The best-known risk for people who dabble with psychedelic states is still, as Wolfson puts it,

“the loss of the monitor that overrides and guides us through the labyrinth of life, as best as it can.”

Wolfson and Vaid told me that I could recover in the waiting room for as long as I needed, but I was impatient to return to the world. I stepped out onto the street into the late afternoon with a wobbliness familiar from years of leaving nightclubs after daybreak, my arms sore as if I had just gotten two

COVID vaccines at once. The apartment buildings along University Place were vaguely changing sizes, so I walked across the street to a nail salon and used a pedicure as an excuse to sit in a chair for forty minutes and let my gaze go out of focus. By the time the polish was dry, I had returned to baseline. I had skipped lunch to avoid getting nauseated, so I found a place where I could eat dumplings. Then I met up with friends in the East Village, where the Friday-evening atmosphere in the streets had the uncorked chaos of a belated spring break.

The next day, I felt different. I did some things I had put off for a long time, and stopped obsessing over other things that had monopolized my thoughts for weeks or months. Perhaps I had been primed to feel this way by the research I had read, but my state of mind seemed only indirectly related to anything I’d seen on my ketamine trip, and entirely unrelated to any kind of therapy. It seemed physical in nature. My mind was working the way I often wish it did. I had, in the past, tried to achieve this state of mind through drinking caffeine, through not drinking caffeine, through exercise, sleep, meditation, antidepressants, healthy eating, Vitamin B12, magnesium, amphetamines, yoga. My mind had always seemed resistant to on-demand engineering. This new feeling was neither an afterglow nor a state of stimulation. It felt like stability. I didn’t want to drink alcohol, or even coffee, out of a fear that the feeling would abandon me; I dreaded being thrown back into my ordinary mind. The feeling lasted a little more than two weeks, and then it went away. The memory of what it had felt like lingered a bit longer, and then it went away, too.

Emily Witt is a staff writer at The New Yorker and the author of “

Future Sex” and “

Nollywood: The Making of a Film Empire.”

The mind-altering drug has been shown to help people suffering from anxiety and depression. But how it helps, who it will serve, and who will profit are open questions.

www.newyorker.com

www.truffle.report

www.truffle.report