The extraordinary therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs, explained

by Sean Illing | VOX | 8 Mar 2019

I spent months talking to psychedelic guides and researchers. Here’s what I learned.

I had a close call on the second night of the ayahuasca ceremony. I saw my teenage self melting into particles and eventually disappearing altogether. I pulled off my sleep mask and saw the people around me shape-shifting into shadows. I thought I was dying, or perhaps losing my grip on reality.

Suddenly, Kat, my guide, appeared and began singing to me. I couldn’t make out the words, but the cadence was soothing. After a minute or two, the dread washed away and I settled back into a peaceful half-sleep.

The 12 of us — nine women and three men — taking ayahuasca in a private home in San Diego were led by two trained guides: Kat and her partner, whom I’ll call Sarah since she requested anonymity due to legal concerns. Together they have more than 20 years of experience working with psychedelics, including ayahuasca, a plant concoction that contains the natural hallucinogen known as DMT.

Kat (her full name is Tina Kourtney) and Sarah work as a team serving psychedelic medicine every month or so in a different city. Their primary role is to create a space in which everyone feels secure enough to drop their emotional guards and open up to the drugs’ potential to change their attitudes, moods, and behaviors.

There’s a lot of unease heading into these ceremonies, especially for people who have never experimented with psychedelics. The fear of what you might see or feel can be overwhelming. But guides like Kat are your port in the storm. When things get turbulent, they respond with a steady, calm hand.

Though psychedelic drugs remain illegal, guided ceremonies, or sessions, are happening across the country, especially in major cities like New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Guiding itself has become a viable profession, both underground and above, as more Americans seek out safe, structured environments to use psychedelics for spiritual growth and psychological healing. This new world of psychedelic-assisted therapy functions as a kind of parallel mental health service. Access to it remains limited, but it’s evolving quicker than you might expect.

A majority of Americans now

support the legalization of marijuana, and while a 2016

public poll on psychedelics suggested they aren’t as favorable, it’s possible that attitudes will shift as the research findings on their

therapeutic potential enter the mainstream. (Author Michael Pollan’s 2018 book

How to Change Your Mind, about his own experiences with psychedelics, helped spread the word. Even

Gwyneth Paltrow has acknowledged their potential in a recent New York Times interview.)

But what would a world in which psychedelics are legal look like? And what sort of cultural structures would we need to ensure that these drugs are used responsibly?

Psychedelic drugs like LSD seeped into American society in the 1960s, and the results were mixed at best. They certainly revolutionized the culture, but they ultimately left us with draconian drug laws and a cultural backlash that pushed psychedelics into the underground.

Today, however, a renaissance is underway. At institutions like

John Hopkins University and

New York University, clinical trials exploring psilocybin as a therapy for treatment-resistant depression, drug addiction, and other anxiety disorders are yielding hopeful results.

In October, the Food and Drug Administration took the extraordinary step of granting psilocybin therapy for depression a

“breakthrough therapy” designation. That means the treatment has demonstrated such potential that the FDA has decided to expedite its development and review process. It’s a sign of how far the research and the public perception of psychedelics have come.

It’s because of this progress that we have to think seriously about what comes next and how we would integrate psychedelics into the broader culture. I’ve spent the past three months talking with guides, researchers, and therapists who are training clinicians to do psychedelic-assisted therapy. I’ve participated in underground ceremonies, and I’ve spoken to people who claim to have conquered their drug addictions after a single psychedelic experience.

Our current laws sanction various poisons, including booze and cigarettes. These are drugs that destroy lives and feed addictions. And yet one of the most striking things about the recent (limited) psychedelic research is that the drugs do not appear to be addictive or have adverse effects when a guide is involved. Many researchers believe these drugs, when used under the supervision of trained professionals, could revolutionize mental health care.

Turn on, tune in, and drop out?

The ’60s countercultural movement was transformational in many ways.

Among other things, it catalyzed the environmental movement, the civil rights movement, contemporary feminism, and the antiwar movement. But it also produced a decades-long backlash against psychedelic drugs that, until recently, made it almost impossible to conduct clinical research.

As late as 1960, psychedelics were fully legal and

widely regarded as a promising line of psychological research. But just a few years later, the political and cultural winds had shifted so dramatically that the country was in a full-blown panic over psychedelics. In 1965, the federal government banned the manufacture and sale of all psychedelic drugs, and shortly thereafter, the companies making these drugs for research ceased production.

Michael Pollan gives an exhaustive account of this in

How to Change Your Mind (a book I highly recommend), but the short version is that psychedelics could never escape the shadow of the countercultural revolution they helped spark.

Timothy Leary, the renegade psychologist and psychedelic evangelist who told kids to “turn on, tune in, and drop out,” is the familiar scapegoat. Leary, the argument goes, was too reckless, too confrontational, and too scary for the mainstream. Leary was such a threat that at one point, he was called the “the most dangerous man in America” by President Richard Nixon.

But Leary’s an easy mark and hardly the sole cause. The culture simply wasn’t ready for psychedelics in the ’60s. The experiences these drugs induce are so powerful that they can amount to a kind of rite of passage. But when they hit the scene, the population had no experience with them, no sense of their significance. As Pollan told me

in an interview earlier this year,

“Young people were having such a radically new kind of experience that the straight culture could not handle.”

Psychedelics were unleashed so fast that there were no cultural structures in place to absorb them, no containers or norms around them. Cultures around the world — from the

ancient Greeks to the indigenous cultures of

the Amazon — have been taking psychedelics for thousands of years, and each one developed rituals for them, led by experienced guides. Because there was no established community in the US, people were left to their own devices. When you combine this with a general ignorance about the drugs themselves, it’s not surprising that things went sideways.

But a lot has changed since the ’60s. The political and cultural landscape is radically different, and far more receptive to psychedelics. Rick Doblin, a longtime advocate for psychedelics and the founder of the

Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), made an interesting point to me when I sat down with him in Washington, DC, recently. (MAPS is a nonprofit research and educational organization that is leading the effort to promote the safe use of psychedelics.)

“In the ’60s,” he said,

“the psychedelic counterculture was a direct challenge to the status quo ... it was about dropping out of the culture. Today, things like yoga and mindfulness meditation are fully integrated into popular culture. We’ve integrated spirituality and all these things that seemed so foreign and alien in the ’60s. So we’ve been preparing culturally for this for 50 years.”

At the same time, psychedelics may also play a role in addressing newer health threats like the

opioid crisis. (70,000 Americans died of opioid overdoses in 2017, more than the total number of Americans that died in Vietnam.) They’re being used to treat populations like

veterans suffering from PTSD, or

cancer patients who are confronting their mortality, or people battling depression.

Psychedelics are becoming tools of healing rather than a threat to the social order. And the scientists and organizations and training institutions leading the way are working within the system to reduce the potential for blowback. This is very different from the approach taken in the ’60s, and so far it’s been a success.

Your mind on psychedelics

Psilocybin is the drug of choice for most researchers in recent years for a variety of reasons. For one, it carries less cultural baggage than LSD, and so study participants are more willing to work with it. Psilocybin also has strong safety data based on studies conducted before prohibition, and so the FDA has allowed a small number of small clinical trials to move forward.

Although the most recent studies are still preliminary and the sample sizes fairly small, the results so far are compelling. In one 2014

Johns Hopkins study, 80 percent of the smokers who participated in psilocybin-assisted therapy remained fully abstinent six months after the trial. By way of comparison,

smoking cessation trials using varenicline (a prescription medication for smoking addiction) has success rates around 35 percent.

In a

separate 2016 study of cancer-related depression or anxiety, 83 percent of 51 participants reported significant increases in well-being or satisfaction six months after a single dose of psilocybin. (Sixty-seven percent said it was one of the most meaningful experiences of their lives.)

A typical psilocybin session lasts somewhere between four and six hours (compared with 12 hours with LSD), yet it produces enduring decreases in depression and anxiety for patients. Which is why researchers like

Roland Griffiths at Johns Hopkins believe psychedelics represents an entirely new model for treating major psychiatric conditions. Conventional treatments like

antidepressants don’t work for a lot of patients and can come with a host of side effects.

This is a big reason why many researchers believe that psychedelics will eventually be rescheduled by the FDA (more on this below) and legalized for medical use — though the timeline on this is far from clear. In November, in fact,

officials in Oregon approved a 2020 ballot measure that would allow medical professionals to conduct psilocybin-assisted therapy. If it passes, Oregon will be the first state to let licensed therapists administer psilocybin. Other states like California are likely to follow suit.

For more on the broad medical potential of psychedelics, I’d urge you to read my

colleague German Lopez’s 2016 review of the science. Here I wanted to focus on how psilocybin works and why it’s so powerful for the people who take it. To understand the clinical side, I traveled to Johns Hopkins to sit down with Alan Davis, a clinical psychologist, and Mary Cosimano, a research coordinator and trained guide. Both help lead the psilocybin sessions at Hopkins.

Researchers at Hopkins have worked with a number of populations since they received approval from the FDA to study psilocybin in 2000 — healthy adults without any psychological issues, cancer patients suffering from anxiety and depression, smokers, and even seasoned meditators.

A key part of the process at Hopkins is what they call “life review.” Before they provide the drug, they want to know who you are, where you’re at in your life, and what kinds of emotional or psychological walls you’ve built up around yourself. The idea is to work with patients to determine what’s holding them back in their lives, and explore how they might overcome it.

Davis and Cosimano both say psilocybin has benefited every population they’ve worked with. “It’s not for everyone,” Cosimano told me,

“but for the right person at the right time, it can be positively transformative.” (They don’t accept patients anywhere on the spectrum of psychosis — it’s just too dangerous.)

The psilocybin sessions are intense and, in some cases, last all day. The rooms they use are a curious blend of drab doctor’s office decor and New Age ornamentation. There’s a vanilla-colored couch covered with embroidered pillows and draped on both sides by South American art. Near the couch, on an end table, is a ceremonial cup and mini sculptures of magic mushrooms; it’s not quite an altar, but it may as well be.

The important thing, Cosimano and Davis say, is to make the patient as comfortable as possible. They even encourage people to bring personal artifacts with them, or letters from loved ones, or basically anything with deep emotional resonance. Much like the underground guides, researchers do everything they can to create a safe psychological space.

Sessions can unfold in multiple directions, depending on the depth of the experience (which is hard to predict) and the mental state of the individual. Mostly, patients are lying on the couch with a sleep mask covering their eyes. Cosimano, Davis, and other clinical guides act as lodestars — holding the patient’s hand and helping them process what they’re seeing and what it means.

“I never get bored with this,” Cosimano told me.

“Every single session is different, every experience is different, and I’m just blown away at being able to witness each person’s journey.”

Yet it’s not entirely clear to the scientists what it is about these experiences that produce such profound changes in attitude, mood, and behavior. Is it a sense of awe? Is it what the American philosopher William James called the “mystical experience,” something so overwhelming that it shatters the authority of everyday consciousness and alters our perception of the world? What’s clear in any case is that psychedelic trips are often beyond the bounds of language.

The best metaphor I’ve heard to describe what psychedelics does to the human mind comes from Robin Carhart-Harris, a psychedelic researcher at Imperial College in London. He said we should think of the mind as a ski slope. Every ski slope develops grooves as more and more people make their way down the hill. As those grooves deepen over time, it becomes harder to ski around them.

Like a ski slope, Carhart-Harris argues, our minds develop patterns as we navigate the world. These patterns harden as you get older. After a while, you stop realizing how conditioned you’ve become — you’re just responding to stimuli in predictable ways. Eventually, your brain becomes what Michael Pollan has aptly called an “uncertainty-reducing machine,” obsessed with securing the ego and locked in uncontrollable loops that reinforce self-destructive habits.

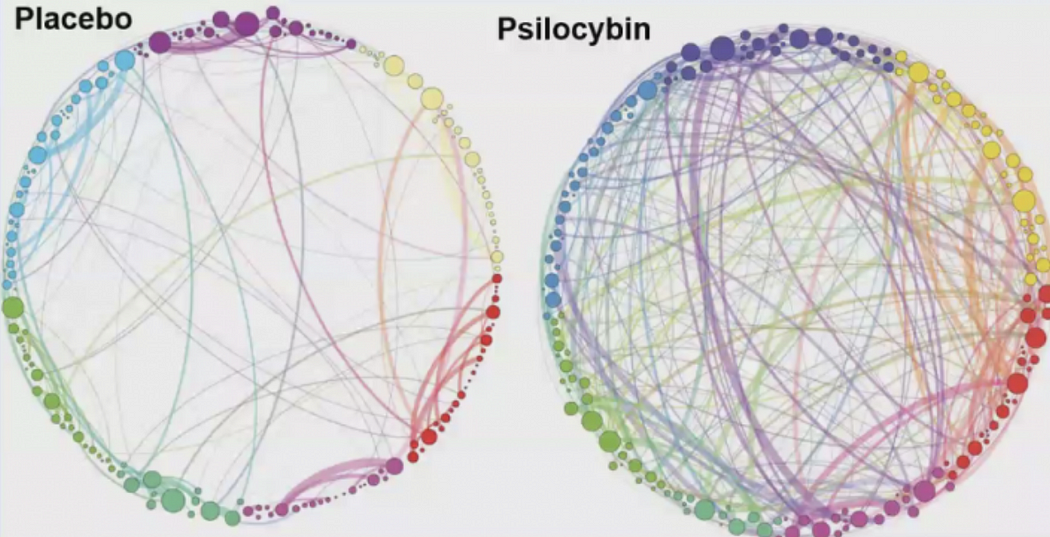

Taking psychedelics is like shaking the snow globe, Carhart-Harris said. It disrupts these patterns and explodes cognitive barriers. It also interacts with what’s called the

default mode network (DMN), the part of the brain associated with mental chatter, self-absorption, memories, and emotions. Anytime you’re anxious about the future or fretting over the past, or engaged in compulsive self-reflection, this part of the brain lights up. When

researchers looked at images of brains on psychedelics, they discovered that the DMN shuts down almost entirely.

Think of it this way: You spend your whole life in this body, and because you’re always at the center of your experience, you become trapped in your own drama, your own narrative. But if you pay close attention, say, in a deep meditation practice, you’ll discover that the experience of self is an illusion. Yet the sensation that there’s a “you” separate and apart from the world is very hard to shake; it’s as though we’re wired to see the world this way.

The only time I’ve ever been able to cut through this ego structure is under the influence of psychedelics (in my case, ayahuasca). I was able to see myself from outside my self, to see the world from the perspective of nowhere and everywhere all at once, and suddenly this horror show of self-regard stopped. And I believe I learned something about the world that I could not have learned any other way, something that altered how I think about, well, everything.

At Johns Hopkins, the drug experience is only one part of the treatment. Equally important is the therapy that follows. People regularly tell researchers that the psilocybin session is the single most personally and spiritually significant experience of their lives, including childbirth and the loss of loved ones.

But there’s a need, Davis said, “to make sense of these experiences and to bring them into your day-to-day life in a way that doesn’t discount the meaning.” That doesn’t necessarily have to be therapy or one-on-one counseling with a guide, but it’s crucial to integrate the experience into your daily life, whether that’s taking up a new practice like yoga or meditation, spending more time in nature, or just cultivating new relationships.

The point is that’s it not enough to take the ride and move on; it’s about establishing new habits, new mental patterns, new ways of being. Psychedelics can kick-start this process, but for many people, at least, that’s all they can do.

When I returned from

my first ayahuasca retreat, I struggled to process what had happened to me. I had no formal help, no instruction, no real support. It’s jarring to slide back into your routine after having your inner world turned upside down like that. I’ve adopted new practices (like meditation), and that has gone a long way in keeping me connected to that initial encounter with psychedelics, but there are limits to what you can do alone.

Recognizing the need for more integration, schools like the

California Institute of Integral Studies and psychedelic researchers like NYU’s Elizabeth Nielson are focused on training professional therapists to work specifically with psychedelic users. Nielson is part of

the Psychedelic Education and Continuing Care Program, which does not conduct psychotherapy but offers instruction to clinicians who want to learn about psychedelics.

“People who have used psychedelics, or will use psychedelics in the future, will need help integrating their experiences, and many will feel safest doing that in a therapist’s office,” she told me.

“That means we’ll need more therapists who understand these experiences and know how to have these kinds of conversations with patients.”

In the meantime, we’ve seen a parallel growth in a more informal support system for people experimenting with psychedelics, one that exists mostly underground.

Psychedelics and the underground

For decades, a community of guides has worked quietly in the shadows, serving psychedelics to people across the country. And they’re not that different from their above-ground counterparts — or at least not as different as you might expect. Many of them have spent years apprenticing under traditional healers in places like Peru and Brazil and follow a strict code of conduct designed to formalize practices and ensure safety.

This was certainly true of Kat, the guide I sat with in San Diego. She studied under a Peruvian mentor for eight years and estimates that she’s used ayahuasca more than 900 times and led hundreds of ceremonies in Europe and the US.

She calls herself a “tone setter,” someone who controls the space. Mostly, she puts everyone at ease by projecting a calm and reassuring presence.

“I take the pulse of the room, and when I have to go over to somebody, I try to be as grounded as the earth itself — that sort of calmness is contagious,” she said.

“The key thing is to be attuned to what’s happening and how people are feeling, and respond to that.”

Her role is a tightrope walk between letting people go through whatever they’re going through and intervening when they’re too close to the abyss. If everyone’s fine, she’s somewhere in the room singing medicine songs and keeping a watchful eye on things. If someone panics, Kat must talk them down, and do it in a way that doesn’t overwhelm everyone else in the room.

Just a few months ago, she told me, a woman at one of her ceremonies was convinced demons had taken over her body. She became hysterical and threatened to call 911. Situations like this arise all the time, and the guide has to figure it out on the fly.

Unlike the clinicians at Hopkins, Kat manages the trips of multiple people at a time, sometimes dozens, and that carries risks. I asked her, why do this? Why risk managing someone reacting in ways she can’t control, or risk going to jail?

“Because it heals people,” she told me.

“I see it every time I hold a circle, every time I walk a group of people through this experience. People enter with one perspective and leave with another. Sometimes that means they see the world with new eyes, and sometimes it means they realize they’re more than their addiction, that their flaws don’t define them.”

Kat, now 43, has had plenty of her own battles. Before discovering ayahuasca 13 years ago on a trip to Peru, she had alcoholism, bulimia, and bipolar disorder — at one point, she attempted suicide.

“The medicine wasn’t a panacea,” she said,

“but it set me on a different path, and basically I dedicated my whole life to this work.”

She tried traditional therapy for several years, mostly to treat her bipolar disorder and bulimia. When that failed, she dabbled in self-help workshops, from

Radical Awakening seminars to

Mastery in Transformational Training courses.

“I was obsessed with finding some sort of relief,” she told me,

“but nothing worked, nothing stuck.”

Everyone who shows up at Kat’s ceremonies has their own reason for being there. Some are psychonauts — people looking to explore altered states of consciousness through the use of psychedelics. Others, like Laura, a 35-year-old woman from Philadelphia, are drawn to plant medicine as a last-ditch effort to conquer an addiction.

In Laura’s case, it was a 14-year addiction to heroin. “I was at the edge of death. I tried every conventional method you can think of — detox, counseling, rehab — and nothing worked,” she told me. She eventually found ibogaine, a psychedelic compound derived from the roots of a West African shrub.

“Ibogaine was like a myth on the streets, this miraculous modality that could reset your brain and save you from the throes of addiction.”

Laura told me that she eventually went to her family and said:

“Put a gun in my mouth and pull the trigger or send me to an ibogaine clinic.” They sent her to an ibogaine treatment center just north of Cancun, where she did a few sessions. She has now been clean for the past eight years.

Ibogaine is not as well researched as psilocybin or LSD, and it’s

comparatively dangerous, but it’s one of the most powerful known psychedelic drugs, and there is

preliminary research suggesting it may be an effective treatment for opioid and cocaine addiction.

Another woman, a 48-year-old from Kansas whom I’ll call April, told me she spent 15 years hooked on Adderall, a stimulant prescribed for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

“It consumed my entire life — every decision, every plan, basically every moment.” She tried several times to quit, but the withdrawal was too much. On a whim, she decided to look into psychedelics and found her way to Kat’s website. A few weeks later, she was sitting in a ceremony.

Her first ayahuasca trip was in September, nearly three months ago, and she hasn’t touched Adderall since.

“The experience was rough,” she said.

“It was like seeing myself and my life through a funhouse mirror, and I could see all the masks I wear, how Adderall had become this crutch, this source of false energy that propelled me through my life. I feel like it recalibrated my whole being.”

These stories are inspiring, but it’s not clear how representative they are. Psychedelics aren’t a magic elixir, and there are

physical and psychological risks to taking them haphazardly, particularly if you’re on medication or have been diagnosed with a psychiatric condition. But used in a proper setting with a trained guide, they can be remarkably therapeutic. (As far as I know, there are no documented “bad trips” in the research literature.)

Kat believes this work could be more impactful if it wasn’t forced underground.

“If this was legal, I’d spend more time with people before and after the experience. I’d want to build up my team and do this aboveground like a normal business and take care of people from start to finish. Because we’re in this legal gray area, people often come into the ceremony and then they’re shot right back into the world, and that can be traumatic.”

I asked Kat if she’s noticed a shift in the sorts of people attending her ceremonies. It used to be mainly the psychonauts, she told me, but lately it’s people, old and young, who want to make peace with mortality or face down deep traumas. She’s working with more and more veterans struggling with PTSD, many of whom tell her they failed to find relief from traditional mental health care.

Still, she hesitated when I asked her about legalization.

“They should absolutely be legal, but I’m not sure they should be legal tomorrow,” she said. “We need a firm foundation in place, a way to keep the reverence around these medicines. If we lose that, if psychedelics become another substance like marijuana, I worry that we’ll blow this up and burn it down like we did in the ’60s.”

Kat’s concern, shared by many people in this space, is that the ceremonial aspects around psychedelics will be lost if they’re legalized overnight. There’s nothing inherently wrong with recreational use, but for those who regard psychedelics with a kind of sacred awe, there’s a genuine fear that these substances will be trivialized if we don’t make this transition wisely.

So how do we integrate psychedelics into the culture?

For better or worse, psychedelics, like all drugs, are going to be used outside the safer contexts of research facilities or private sessions with experienced guides. According to Geoff Bathje, a psychologist at Adler University who works with high-trauma patients, the question is therefore,

“What sort of harm reductions do we need to help protect people?”

Several people I spoke with pointed to the “harm reduction” model. Harm reduction focuses on reducing the risks associated with drug use, as opposed to punitive models aimed at eliminating use altogether. It’s a practical and humane approach that has worked well in

places like Portugal, where all drugs for personal use have been decriminalized.

Although the harm reduction model isn’t typically associated with psychedelics, the principles apply all the same.

For Bathje, it’s about doing good drug education in the general population,

“making sure people understand the risks involved with psychedelics — how they can be misused, how people can be exploited when under the influence, etc.” There are already national harm reduction groups like

Zendo Project, which is sponsored by MAPS, that focus on peer-to-peer counseling for people experimenting with psychedelics.

Bathje and some of his colleagues have established a harm reduction group in Chicago called Psychedelic Safety Support and Integration. The goal is to promote safety and help people process their psychedelic experiences. It’s a critical container that brings in the community, spreads awareness of the risks associated with psychedelic drug use, and creates a space for connection.

At the moment, there’s a gap between the harm reduction movement and the psychedelic research community.

“You go to a psychedelics conference and it’s focused on the science and the therapeutic potential,” Bathje said,

“and the general assumption is that if we just produce good science, these drugs will get approved as medicines and everything will just fall into place.”

“If you attend a harm reduction conference,” he added,

“it’s all about cultural change and how politicians don’t care about the science. The focus is much more on organizing and who has the power and how we can reduce risks and do things safely.” This is partly why the harm reduction movement can be useful to psychedelics. Science may be critical to legalization, but public health programs would have to help integrate these drugs into the broader culture.

Harm reduction groups like Bathje’s and the Zendo Project are the best models we have for this sort of integration, and we’d need to scale them up if psychedelics are legalized for medicinal use.

There are reasons to be cautious, but we should welcome the evolution of psychedelic research

After spending months thinking about these issues and talking to people involved at nearly every level, I’m convinced that the new culture of therapeutic psychedelics is evolving quickly. Just this week, a

group of citizens in Denver gathered enough signatures to approve a ballot measure in the spring that would decriminalize magic mushrooms.

As Rick Doblin pointed out, the social and political milieu is much different today than it was in the ’60s, and there’s no reason to suspect a similar backlash. The cultural containers and the knowledge are there, and they could increasingly be brought out of the shadows.

What this transition on a larger scale will look like, and how long it will take, is less clear. Advocates like Doblin seem wise to continue playing the long game. Given the progress of the research, it’s possible that psilocybin will be recategorized from a schedule 1 drug (drugs with no known medical value) to a schedule 4 drug (drugs with a low potential for abuse and a known medical value) in the next three or four years.

The process of rescheduling drugs, however, is a bit muddled. Under federal law, the US attorney general can move to reschedule drugs on their own, but they are required to gather data and medical research from the secretary of health and human services before doing so. Congress can also pass laws to change the scheduling of drugs, and could, if they chose, overrule an attorney general.

We’re unlikely to see much progress on this front under the current administration, but the political winds can shift in a hurry, especially if the research continues apace. That the Drug Enforcement Agency is already comfortable with the possibility of rescheduling psychedelics is a very positive sign.

“We’re happy to see the research progressing at institutions like Johns Hopkins,” Rusty Payne, the DEA’s spokesperson, told me in a phone interview.

“When the scientific and medical community come to the DEA and say, ‘This should be a medicine, this should be recategorized as a schedule 4 or 5 instead of a schedule 1’; then we will act accordingly.”

Support for psychedelics is also one of those rare issues that can, in some cases, cut across conventional political lines.

Rebekah Mercer, the billionaire Republican financier and co-owner of Breitbart, has donated a $1 million to MAPS to fund their studies focused on veterans with PTSD. As the research advances, we could see more bipartisan support like this.

One big remaining question has to do with access. If you spend any time at all in the psychedelic subculture, you can’t help but notice that it consists mostly of privileged white people. This is largely a product of who’s holding these spaces, how much they cost (anywhere from $600 to well over $1,000 per session), where they’re being held, and the networks of people propping them up. That many people simply don’t know about the therapeutic potential of psychedelics is yet another barrier. All of this has to change, and hopefully it will when psychedelics aren’t relegated to the underground.

Within the psychedelic community itself, there are concerns about commodification. Companies like

Compass Pathways are seeking to turn psilocybin into a pharmaceutical product. (Compass’s psilocybin study is the one that received the

breakthrough therapy designation from the FDA in October.)

Compass began as a nonprofit venture with an interest in starting a psychedelic hospice center but has since pivoted to a for-profit approach. With major investors like Peter Thiel behind it, Compass might dominate the medical supply chain of psychedelics from synthesis to therapy. It’s also impeding the research efforts of nonprofit companies like

Usona that are developing their own psychedelic medicines. If the market becomes monopolized, or if a few pharmaceutical companies control critical patents, lots of people could be priced out of access.

Despite all these concerns, we should welcome the evolution of psychedelic research. We need bigger studies, and we need to include more diverse populations in them to learn as much as we can about how these drugs work. As Richard Friedman, a clinical psychiatrist at Cornell University, told me,

“I’m all for optimism, but show me the data. I embrace the enthusiasm for the therapeutic potential of psychedelics ... but as to whether it’s justified, the answer will be the data. And nothing but the data.”

So far the data is encouraging, yet there’s plenty we don’t yet understand. But we know enough to say that psychedelics are powerful tools for reducing suffering at least for some people. And we simply don’t have enough of these tools to justify their prohibition.

I spent months talking to psychedelic guides and researchers. Here’s what I learned.

www.vox.com

www.statnews.com

www.statnews.com