I would like to start my talk by asking you some questions. How many of you have experienced any of the following forms of non-ordinary states of consciousness? :

1. Intense experiences during spiritual practice?

2. Experiences in deep experiential psychotherapy?

3. Experiences induced by psychedelic substances?

4. Experiences during powerful shamanic rituals?

5. Near-death experiences?

6. Intense spontaneous experiences in everyday life (“spiritual emergencies”)?

Look around and see the number of hands. This is clearly a somewhat self-selected audience, but we see the same response whenever and wherever we give our workshops and lectures. And now, how many of you have experienced Holotropic Breathwork that Christina and I developed when we lived at the Esalen Institute? How many of you participated in the pre-conference Holotropic Breathwork workshop here in Moscow? You might know by now that this pre-conference breathwork set a new record for large groups; it had over 460 participants. Russia has now its own training for Holotropic Breathwork facilitators led by Volodya Maykov, so that those of you interested in having this experience can easily find the opportunity.

I have asked these questions because my lecture today will be based on observations and experiences from over fifty years of my research of non-ordinary states of consciousness. And it is much easier to understand this material if we can relate it to our own personal experiences. People who have not experienced these states often find it difficult to believe that the phenomena I will be talking about are even possible.

I have been talking thus far about «non-ordinary states of consciousness», but I have actually been researching all these years a very important subgroup of non-ordinary states that I call "holotropic." Before I continue my talk, I would like to clarify the terms I will be using. All these years, my primary interest has been to explore the healing, transformative, and evolutionary potential of non-ordinary states of consciousness and their great value as a source of new revolutionary data about consciousness, the human psyche, and the nature of reality. From this perspective, the term “altered states of consciousness” commonly used by mainstream clinicians and theoreticians is not appropriate, because of its one-sided emphasis on the distortion or impairment of the “correct way” of experiencing oneself and the world. (In colloquial English and in veterinary jargon, the term “alter” is used to signify castration of family dogs and cats).

Even the somewhat better term “non-ordinary states of consciousness” is too general, since it includes a wide range of conditions that are not relevant from the point of view of our discussion, such as trivial deliria caused by infectious diseases, abuse of alcohol, or circulatory and degenerative diseases of the brain. These are associated with disorientation, impairment of intellectual functions, and subsequent amnesia.

I will talk today about a large subgroup of non-ordinary states of consciousness that are of great theoretical and practical importance. These are the states that novice shamans experience during their initiatory crises and later induce in their clients. Ancient and native cultures have used these states in rites of passage and in their healing ceremonies. They were described by mystics of all ages and initiates in the ancient mysteries of death and rebirth. Procedures inducing these states were also developed and used in the context of the great religions of the world – Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Judaism, and Christianity.

The importance of non-ordinary states of consciousness for ancient and aboriginal cultures is reflected in the amount of time and energy that the members of these human groups dedicated to the development of “technologies of the sacred,” various procedures capable of inducing them for ritual and spiritual purposes. These methods combine in various ways drumming and other forms of percussion, music, chanting, rhythmic dancing, changes of breathing, and cultivation of special forms of awareness. Extended social and sensory isolation, such as stay in a cave, desert, arctic ice, or in high mountains, also play an important role as means of inducing this category of non-ordinary states. Extreme physiological interventions used for this purpose include fasting, sleep deprivation, dehydration, use of powerful laxatives and purgatives, and even infliction of severe pain, body mutilation, and massive bloodletting. By far the most effective tool for inducing healing and transformative non-ordinary states has been ritual use of psychedelic plants.

When I recognized the unique nature of this category of non-ordinary states of consciousness, I found it difficult to believe that contemporary psychiatry does not have a specific category and term for these theoretically and practically important experiences. Because I felt strongly that they deserve to be distinguished from “altered states of consciousness” and not be seen as manifestations of serious mental diseases, I started referring to them as holotropic. This composite word means literally "oriented toward wholeness" or "moving toward wholeness" (from the Greek holos = whole and trepein = moving toward or in the direction of something). The word holotropic is a neologism, but it is related to a commonly used term heliotropism – the property of plants to always turn in the direction of the sun.

The name holotropic suggests something that might come as a surprise to an average Westerner - that in our everyday state of consciousness we identify with only a small fraction of who we really are and do not experience the full extent of our being. Holotropic states of consciousness have the potential to help us recognize that we are not “skin-encapsulated egos” – as British philosopher and writer Alan Watts called it – and that, in the last analysis, we are commensurate with the cosmic creative principle itself. Or that – using the statement by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, French paleontologist and philosopher – “we are not human beings having spiritual experiences, we are spiritual beings having human experiences” (Teilhard de Chardin 1975)

This astonishing idea is not new. In the ancient Indian Upanishads, the answer to the question: “Who am I?” is “Tat tvam asi.” This succinct Sanskrit sentence means literally: “Thou art That,” or “You are Godhead.” It suggests that we are not “namarupa” – name and form (body/ego), but that our deepest identity is with a divine spark in our innermost being (Atman) which is ultimately identical with the supreme universal principle that created the universe (Brahman). And Hinduism is not the only religion that has made this discovery. The revelation concerning the identity of the individual with the divine is the ultimate secret that lies at the mystical core of all great spiritual traditions. The name for this principle could thus be the Tao, Buddha, Cosmic Christ, Allah, Great Spirit, Sila, and many others. Holotropic experiences have the potential to help us discover our true identity and our cosmic status. Sometimes this happens in small increments, other times in the form of major breakthroughs.

Psychedelic research and the development of intensive experiential techniques of psychotherapy moved holotropic states from the world of healers of preliterate cultures into modern psychiatry and psychotherapy. Therapists who were open to these approaches and used them in their practice were able to confirm the extraordinary healing potential of holotropic states and discovered their value as goldmines of revolutionary new information about consciousness, human psyche, and nature of reality. I became aware of the remarkable properties of holotropic states in 1956 when I volunteered as a beginning psychiatrist for an experiment with LSD-25. During this experiment, in which the pharmacological effect of LSD was combined with exposure to powerful stroboscopic light, I had an overwhelming experience of cosmic consciousness (Grof 2006).

This experience inspired in me a lifelong interest in holotropic states; research of these states has become my passion, profession, and vocation. Since that time, most of my clinical and research activities have consisted of systematic exploration of the therapeutic, transformative, and evolutionary potential of these states. The five decades that I have dedicated to consciousness research have been for me an extraordinary adventure of discovery and self-discovery. I spent approximately half of this time conducting therapy with psychedelic substances, first in Czechoslovakia in the Psychiatric Research Institute in Prague and then in the United States, at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center in Baltimore, where I participated in the last surviving American psychedelic research program. Since 1975, my wife Christina and I have worked with Holotropic Breathwork, a powerful method of therapy and self-exploration that we jointly developed at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California. Over the years, we have also supported many people undergoing spontaneous episodes of non-ordinary states of consciousness - psychospiritual crises or “spiritual emergencies,” as Christina and I call them (Grof and Grof 1989, Grof and Grof 1991).

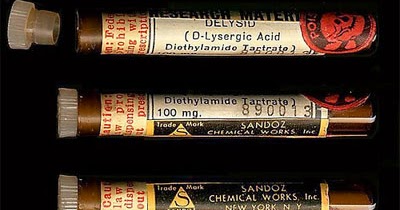

In psychedelic therapy, holotropic states are brought about by administration of mind-altering substances, such as LSD, psilocybine, mescaline, and tryptamine or amphetamine derivatives. In holotropic breathwork, consciousness is changed by a combination of faster breathing, evocative music, and energy-releasing bodywork. In spiritual emergencies, holotropic states occur spontaneously, in the middle of everyday life, and their cause is usually unknown. If they are correctly understood and supported, holotropic states have an extraordinary healing, transformative, and even evolutionary potential.

In addition, I have been more peripherally involved in many disciplines that are, more or less directly, related to holotropic states of consciousness. I have spent much time exchanging information with anthropologists and have participated in sacred ceremonies of native cultures in different parts of the world with and without the ingestion of psychedelic plants, such as peyote, ayahuasca, and magic mushrooms. This involved contact with various North American, Mexican, South American, and African shamans and healers. I have also had extensive contact with representatives of various spiritual disciplines, including Vipassana, Zen, and Vajrayana Buddhism, Siddha Yoga, Tantra, and the Christian Benedictine order.

Another area that has received much of my attention has been thanatology, the young discipline studying near-death experiences and the psychological and spiritual aspects of death and dying. In the late 1960s and early 1970s I participated in a large research project studying the effects of psychedelic therapy in individuals dying of cancer. I should also add that I have had the privilege of personal acquaintance and experience with some of the great psychics and parapsychologists of our era, pioneers of laboratory consciousness research, and therapists who developed and practiced powerful forms of experiential therapy that induce holotropic states of consciousness.

My initial encounter with holotropic states was very difficult and intellectually, as well as emotionally, challenging. In the early years of my laboratory and clinical research with psychedelics, I was daily bombarded with experiences and observations, for which my medical and psychiatric training had not prepared me. As a matter of fact, I was experiencing and seeing things, which - in the context of the scientific worldview I obtained during my medical training - were considered impossible and were not supposed to happen. And yet, those obviously impossible things were happening all the time. I have described these “anomalous phenomena” in my articles and books (Grof 2000, 2006).

In the late 1900s, I received a phone call from Jane Bunker, my editor at State University New York Press, which published many of my books. She asked me if I would consider writing a book that would summarize the observations from my research in one volume that would serve as an introduction to my already published books. And she added: «It would be great, if you could specifically focus on all the experiences and observations from your research that current scientific theories cannot explain and also suggest the revisions in our thinking that would be necessary to account for these revolutionary findings.» As you can see, this was what we call a 'tall order!' However, it was also a great opportunity. My seventieth birthday was rapidly approaching and a new generation of facilitators was conducting our Holotropic Breathwork training all over the world. We needed a manual covering the material that was taught in our training modules. And here was an offer to provide it for us.

The result of this exchange was a book with a deliberately provocative title: «Psychology of the Future.» The radical revisions in our understanding of consciousness and the human psyche in health and disease that I suggested in this work fall into the following categories:

1. The Nature of Consciousness and Its Relationship to Matter

2. Cartography of the Human Psyche

3. Architecture of Emotional and Psychosomatic Disorders

4. Effective Therapeutic Mechanisms

5. Strategy of Psychotherapy and Self-Exploration

6. The Role of Spirituality in Human Life

7. The Importance of Archetypal Psychology and Transit Astrology

In my opinion, these are the areas that require drastic changes in our thinking. Without them, a large array of the experiences and observations from the research of holotropic states will remain mystifying «anomalous phenomena». Considering my own initial resistance to these bewildering findings, I expect that these suggestions will encounter strong resistance in the academic community. This is understandable, considering the scope and radical nature of the above conceptual revisions. We are not talking here about minor patchwork, technically called «ad hoc hypotheses», but a major fundamental overhaul. The resulting conceptual cataclysm would be comparable in its nature and scope to the revolution that physicists had to face in the first three decades of the twentieth century when they had to move from Newtonian to quantum-relativistic physics. And, in a sense, it would represent a logical completion of the radical change in understanding reality that has already happened in physics.

In the history of science, individuals who suggested such far-reaching changes in the dominant paradigm have not enjoyed very enthusiastic reception; their ideas were initially dismissed as products of ignorance, poor judgment, bad science, fraud, or even insanity. In several days, I will begin the eightieth year of my life; this is the time when researchers often try to review their professional carer and outline the conclusions at which they have arrived. More than half a century of research of holotropic states – my own, as well as that of many of my transpersonal colleagues - has amassed so much supportive evidence for a radically new understanding of consciousness and the human psyche that I am willing to take my chance and describe this new vision in its entirety, fully aware of its controversial nature. The fact that it challenges the most fundamental metaphysical assumptions of materialistic science should not be a sufficient reason for rejecting it. Whether it will be refuted or accepted should be determined by unbiased future research of holotropic states.

The Nature of Consciousness and its Relationship to Matter

According to the current scientific worldview, consciousness is an epiphenomenon of material processes; it allegedly emerges out of the complexity of the neurophysiological processes in the brain. This thesis is presented with great authority as an obvious fact that has been proven beyond any reasonable doubt. However, if we subject it to closer scrutiny, we discover that it is a basic metaphysical assumption that is not supported by facts and actually contradicts the findings of modern consciousness research. We have ample clinical and experimental evidence showing deep correlations between the anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry of the brain, on the one hand, and conscious processes, on the other. However, none of these findings proves unequivocally that consciousness is actually generated by the brain.

The origin of consciousness from matter is simply assumed as an obvious and self-evident fact based on the belief in the primacy of matter in the universe. In the entire history of science, nobody has ever offered a plausible explanation how consciousness could be generated by material processes, or even suggested a viable approach to the problem. We can use here as illustration the book by Francis Crick The Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul; its jacket carried a very exciting promise: “Nobel Prize-winning Scientist Explains Consciousness.”

Crick’s “astonishing hypothesis” was succinctly stated at the beginning of his book:

”You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules. Who you are is nothing but a pack of neurons.” To simplify the problem of consciousness, Crick narrows it to the problem of optical perception. He presents impressive experimental evidence showing that the visual perception is associated with distinct physiological, biochemical, and electrical processes in the optical system from the retina to the suboccipital cortex. There the discussion ends as if the problem of consciousness was satisfactorily solved.

In reality, this is where the problem begins. What is it that is capable of transforming chemical and electric processes in the brain into a conscious experience of a reasonable facsimile of the object we are observing, in full color, and project it into three-dimensional space? The formidable problem of the relationship between phenomena – things as we perceive them – and noumena – things as they truly are in themselves (Dinge an sich) was clearly articulated by Immanuel Kant. Scientists focus their efforts on the aspect of the problem where they can find answers – the material processes in the brain. The much more mysterious problem – how physical processes in the brain generate consciousness – does not receive any attention, because it is incomprehensible and cannot be solved.

The attitude that Western science has adopted in regard to this issue resembles the famous Sufi story. On a dark night, a man is crawling on his knees under a candelabra lamp. Another man sees him and asks:

"What are you doing? Are you looking for something?" The man answers that he is searching for a lost key and the newcomer offers to help. After some time of unsuccessful joint effort, the helper is confused and feels the need for clarification.

"I don't see anything! Are you sure you lost it here?" he asks. The owner of the lost key shakes his head; he points his finger to a dark area outside of the circle illuminated by the lamp and replies:

"Not here, over there!" The helper is puzzled and inquires further:

"So why are we looking for it here and not over there?" "Because it is light here and we can see. Over there, we would not have a chance!"

In a similar way, materialistic scientists have systematically avoided the problem of the origin of consciousness, because this riddle cannot be solved within the context of their conceptual framework. The idea that consciousness is a product of the brain naturally is not completely arbitrary. Its proponents usually refer to the results of many neurological and psychiatric experiments and to a vast body of very specific clinical observations from neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, to support their position. The evidence for a close connection between the anatomy of the brain, neurophysiology, and consciousness is unquestionable and overwhelming. What is problematic is not the nature of the presented evidence but the interpretation of the results, the logic of the argument, and the conclusions that are drawn from these observations. While these experiments clearly show that consciousness is closely connected with the neurophysiological and biochemical processes in the brain, they have very little bearing on the nature and origin of consciousness.

This can be illustrated by looking at the relationship between the TV set and the television program. The situation here is much clearer, since it involves a system that is human-made and its operation well known. The final reception of the television program, the quality of the picture and of the sound, depends in a very critical way on proper functioning of the TV set and on the integrity of its components. Malfunctioning of its various parts results in very distinct and specific changes of the quality of the program. Some of them lead to distortions of form, color, or sound, others to interference between the channels. Like the neurologist who uses changes in consciousness as a diagnostic tool, a television mechanic can infer from the nature of these anomalies which parts of the set and which specific components are malfunctioning. When the problem is identified, repairing or replacing these elements will correct the distortions.

Since we know the basic principles of the television technology, it is clear to us that the set simply mediates the program and that it does not generate it or contribute anything to it. We would laugh at somebody who would try to examine and scrutinize all the transistors, relays, and circuits of the TV set and analyze all its wires in an attempt to figure out how it creates the programs. Even if we carry this misguided effort to the molecular, atomic, or subatomic level, we will have absolutely no clue why, at a particular time, a Mickey Mouse cartoon, a Star Trek sequence, or a Hollywood classic appear on the screen. The fact that there is such a close correlation between the functioning of the TV set and the quality of the program does not necessarily mean that the entire secret of the program is in the set itself. Yet this is exactly the kind of conclusion that traditional materialistic science drew from comparable data about the brain and its relation to consciousness.

There actually exists ample evidence suggesting exactly the opposite, namely that consciousness can under certain circumstances operate independently of its material substrate and can perform functions that reach far beyond the capacities of the brain. This is most clearly illustrated by the existence of out-of-body experiences (OOBEs). These can occur spontaneously, or in a variety of facilitating situations that include shamanic trance, psychedelic sessions, hypnosis, experiential psychotherapy, and particularly near-death situations. In all these situations consciousness can separate from the body and maintain its sensory capacity, while moving freely to various close and remote locations. Of particular interest are "veridical OOBEs," where independent verification proves the accuracy of perception of the environment under these circumstances. In near-death situations, veridical OOBEs can occur even in people who are congenitally blind for organic reasons. There are many other types of transpersonal phenomena that can mediate accurate information about various aspects of the universe that had not been previously received and recorded in the brain (Grof 2000).

Materialistic science has not been able to produce any convincing evidence that consciousness is a product of the neurophysiological processes in the brain. It has been able to maintain its present position only by ignoring, misinterpreting, and even ridiculing a vast body of observations indicating that consciousness can exist and function independently of the body and of the physical senses. This evidence comes from parapsychology, anthropology, LSD research, experiential psychotherapy, thanatology, and the study of spontaneously occurring holotropic states of consciousness. All these disciplines have amassed impressive data demonstrating clearly that human consciousness is capable of doing many things that the brain (as understood by mainstream science) could not possibly do and that it is a primary and further irreducible aspect of existence.

The above observations demonstrate without any reasonable doubt that consciousness is not a product of the brain and thus an epiphenomenon of matter. It is more likely at least an equal partner of matter, or possibly superordinated to it. The matrices for many of the above experiences clearly are not contained in the brain, but are stored in some kinds of immaterial fields or in the field of consciousness itself. The most promising developments in hard sciences offering models for transpersonal experience are David Bohm’s idea of the implicate order (Bohm 1980), Rupert Sheldrake’s concept of morphogenetic fields.

Cartography of the Human Psyche

Traditional academic psychiatry and psychology use a model of the human psyche that is limited to postnatal biography and to the individual unconscious as described by Sigmund Freud. According to Freud, our psychological history begins after we are born; the newborn is a tabula rasa, a clean slate. Our psychological functioning is determined by an interplay between biological instincts and influences that have shaped our life since we came into this world – the quality of nursing, the nature of toilet training, various psychosexual traumas, development of the superego, our reaction to the Oedipal triangle, and conflicts and traumatic events in later life. Who we become and how we psychologically function is determined by our postnatal personal and interpersonal history.

The Freudian individual unconscious is also essentially a derivative of our postnatal history; it is a repository of what we have forgotten, rejected as unacceptable,

and repressed. This underworld of the psyche, or the id as Freud called it, is a realm dominated by primitive instinctual forces. Freud described the relationship between the conscious psyche and the unconscious using his famous image of the submerged iceberg. What we thought to be the totality of the psyche is just a small part of it, like the section of the iceberg showing above the surface. Psychoanalysis discovered that a much larger part of the psyche, comparable to the submerged part of the iceberg, is unconscious and, unbeknown to us, governs our thought processes and behavior.

This model, modified, expanded, and refined, has been adopted by mainstream psychology and psychiatry. In the work with holotropic states of consciousness induced

by psychedelics and various non-drug means, as well as those occurring spontaneously, this model proves to be painfully inadequate. To account for all the phenomena occurring in these states, we must drastically revise our understanding of the dimensions of the human psyche. Besides the postnatal biographical level that it shares with traditional psychology, the new expanded cartography includes two additional large domains.

The first of these domains can be referred to as perinatal, because of its close connection with the trauma of biological birth. This region of the unconscious contains the memories of what the fetus experienced in the consecutive stages of the birth process, including all the emotions and physical sensations involved. These memories form four distinct experiential clusters, each of which is related to one of the stages of childbirth. We can refer to them as Basic Perinatal Matrices (BPM I-IV). BPM I consists of memories of the advanced prenatal state just before the onset of the delivery. BPM II is related to the first stage of the birth process when the uterus contracts, but the cervix is not yet open. BPM III reflects the struggle to be born after the uterine cervix dilates. And finally, BPM IV holds the memory of the emerging into the world, the birth itself. The content of these matrices is not limited to fetal memories; each of them also represents a selective opening into the areas of the historical and archetypal collective unconscious, which contain motifs of similar experiential quality. Detailed description of the phenomenology and dynamics of perinatal matrices can be found in my various publications (Grof 1975, 2000).

The official position of academic psychiatry is that biological birth is not recorded in memory and does not constitute a psychotrauma. The usual reason for denying the possibility of birth memory is that the cerebral cortex of the newborn is not mature enough to mediate experiencing and recording of this event. More specifically, the cortical neurons are not yet completely covered with protective sheaths of a fatty substance called myelin. Surprisingly, the same argument is not used to deny the existence and importance of memories from the time of nursing, a period that immediately follows birth. The psychological significance of the experiences in the oral period and even “bonding” - the exchange of looks and physical contact between the mother and child immediately after birth - is generally recognized and acknowledged by mainstream obstetricians, pediatricians, and child psychiatrists.

The myelinization argument makes no sense and is in conflict with scientific evidence of various kinds. It is well known that memory exists in organisms that do not have a cerebral cortex at all, let alone a myelinized one. In 2001, American neuroscientist of Austrian origin, Erik Kandel, received a Nobel Prize in physiology for his research of memory mechanisms of the sea slug Aplysia, an organism incomparably more primitive than the newborn child. The assertion that the newborn is not aware of being born and is not capable to form a memory of this event is also in sharp conflict with extensive fetal research showing the extreme sensitivity of the fetus already in the prenatal stage (Tomatis 1991, Whitwell 1999).

The second transbiographical domain of the new cartography can best be called transpersonal, because it includes a rich array of experiences in which consciousness transcends the boundaries of the body/ego and the usual limitations of linear time and three-dimensional space. This results in experiential identification with other people, groups of people, other life forms, and even elements of the inorganic world. Transcendence of time provides experiential access to ancestral, racial, collective, phylogenetic, and karmic memories. Yet another category of transpersonal experiences can take us into the realm of the collective unconscious that the Swiss psychiatrist C. G. Jung called archetypal. This region harbors mythological figures, themes, and realms of all the cultures and ages, even those of which we have no intellectual knowledge (Jung 1959).

In its farthest reaches, individual consciousness can identify with the Universal Mind or Cosmic Consciousness, the creative principle of the universe Probably the

most profound experience available for direct experience in holotropic states is identification with the Supracosmic and Metacosmic Void (Sanskrit sunyata), primordial Emptiness and Nothingness that is conscious of itself. The Void has a paradoxical nature; it is a vacuum, because it is devoid of any concrete forms, but it is also a plenum, since it seems to contain all of creation in a potential form.

The classification of transpersonal experiences I have described in my books is strictly phenomenological and not hierarchical as it is presented in yogic literature and in the writings of Ken Wilber; it does not specify the levels of consciousness on which they occur. However, it is not difficult to arrange transpersonal experiences in my classification of in such a way that they closely parallel Wilber's’s description of the levels of spiritual evolution (Wilber 1980). Constructing his map of psychospiritual development, Wilber used material from ancient spiritual literature, primarily from Vedanta Hinduism and Theravada Buddhism. My own data are drawn from clinical observations in contemporary populations in a number of European countries, North and South America, and Australia, complemented by some limited experience with Japanese and East Indian groups.

This research has provided empirical evidence for the existence of most of the experiences included in Wilber’s developmental scheme. It has also shown that the descriptions in ancient spiritual sources that Wilber refers to are still to a great extent relevant for modern humanity. However, examples Wilber uses for various levels of psychospiritual development are rather scanty and incomplete; incorporating the observations from the study of holotropic states into his scheme requires some important additions, modifications, and adjustments.

Wilber’s scheme of the post-centauric spiritual domain includes the lower and higher subtle level, lower and higher causal level, and the Ultimate or Absolute. According to him, the low subtle, or astral-psychic, level of consciousness is characterized by a degree of differentiation of consciousness from the mind and body which goes beyond that achieved on the level of the centaur. The astral level, in Wilber’s own words, "includes, basically, out-of-body experiences, certain occult knowledge, the auras, true magic, ‘astral travel,’ and so on.” Ken's description of the psychic level includes various ‘psi’ phenomena: ESP, precognition, clairvoyance, psychokinesis, and others. He also refers in this connection to Patanjali's Sutras that include on the subtle level all the paranormal powers, mind-over-matter phenomena, or siddhis. In the higher subtle realm, consciousness differentiates itself completely from the ordinary mind and becomes what can be called the ‘overself’ or ‘overmind.’ Wilber places in this region high religious intuition and inspiration, visions of divine light, audible illuminations, and higher presences - spiritual guides, angelic beings, ishtadevas, Dhyani-Buddhas, and God's archetypes, which he sees as high archetypal forms of our own being.

Like the subtle level, the causal level can be subdivided into lower and higher. Wilber points out that the lower causal realm is manifested in a state of consciousness known as savikalpa samadhi, the experience of final God, the ground, essence, and source of all the archetypal and lesser-god manifestations encountered in the subtle realms. The higher causal realm then involves a "total and utter transcendence and release into Formless Consciousness, Boundless Radiance." Wilber refers in this context to nirvikalpa samadhi of Hinduism, nirodh of Hinayana Buddhism, and to the eighth of the ten ox-herding pictures of Zen Buddhism.

On Wilber's last level, that of the Absolute, Consciousness awakens as its Original Condition and Suchness (tathagata), which is, at the same time, all that is, gross, subtle, or causal. The distinction between the witness and the witnessed disappears and the entire World Process then arises, moment to moment as one's own Being, outside of which and prior to which nothing exists.

In a hierarchical classification based on my own data, I would include in the low subtle or astral-psychic level experiences that involve elements of the material world, but provide information about them in a way that is radically different from our everyday perception. Here belong, above all, experiences that are traditionally studied by portray them in their universal form (e.g. the Great Mother Goddess) or in the form of their specific cultural manifestations ( e.g. Virgin Mary, Isis, Cybele, Parvati, etc.).

Over the years, I have had the privilege to be in psychedelic and Holotropic Breathwork sessions of people who had experiences of the lower and higher causal realms and possibly even those of the Absolute. I have also had personal experiences that I believe qualify for these categories. In my classification these episodes are described under such titles as experiences of the Demiurg, Cosmic Consciousness, Absolute Consciousness, or Supracosmic and Metacosmic Void.

The existence and nature of transpersonal experiences violates some of the most basic assumptions of materialistic science. They imply such seemingly absurd notions as relativity and arbitrary nature of all physical boundaries, nonlocal connections in the universe, communication through unknown means and channels, memory without a material substrate, non-linearity of time, or consciousness associated with all living organisms, and even inorganic matter. Many transpersonal experiences involve events from the microcosm and the macrocosm, realms that cannot normally be reached by unaided human senses, or from historical periods that precede the origin of the solar system, formation of planet earth, appearance of living organisms, development of the nervous system, and emergence of homo sapiens.

Having spent more than half a century studying transpersonal experiences, I have no doubt that they are ontologically real and are not products of metaphysical speculation, human imagination, or pathological processes in the brain. It would be erroneous to dismiss them as products of fantasy, primitive superstition, or a

manifestation of mental disease, as has so frequently been done. Anybody attempting to do that would have to offer a plausible explanation why these experiences have in the past been described so consistently by people of various races, cultures, and historical periods. He or she would also have to account for the fact that these experiences continue to emerge in modern populations under such diverse circumstances as sessions with various psychedelic substances, during experiential psychotherapy, in meditation of people involved in systematic spiritual practice, in near-death experiences, and in the course of spontaneous episodes of psychospiritual crisis. Detailed discussion of the transpersonal domain, including descriptions and examples of various types of transpersonal experiences can be found in my various publications (Grof 1975, 1987, and 2000).

In view of this vastly expanded model of the psyche, we could now paraphrase Freud’s simile of the psyche as an iceberg. We could say that everything Freudian analysis has discovered about the psyche represents just the top of the iceberg showing above the water. Research of holotropic states has made it possible to explore the colossal rest of the iceberg hidden under water, which has escaped the attention of Freud and his followers, with the exception of the remarkable renegades Otto Rank and C. G. Jung. Mythologist Joseph Campbell, known for his incisive Irish humor, used a different metaphor:

“Freud was fishing while sitting on a whale.”

The Nature, Function, and Architecture of Emotional and Psychosomatic Disorders

To explain various emotional and psychosomatic disorders that do not have an organic basis (“psychogenic psychopathology”), traditional psychiatrists use the superficial model of the psyche limited to postnatal biography and the individual unconscious. They believe that these conditions originate in infancy and childhood as a result of various emotional traumas and interpersonal dynamics in the family. There seems to be general agreement in schools of dynamic psychotherapy that the depth and seriousness of these disorders depends on the timing of the original traumatization.

Thus, according to classical psychoanalysis, the origin of alcoholism, narcotic drug addiction, and manic-depressive disorders can be found in the oral period of

libidinal development, obsessive-compulsive neurosis has its roots in the anal stage, phobias and conversion hysteria result from traumas incurred in the “phallic phase” and at the time of the Oedipus and Electra complex, and so on (Fenichel 1945). Later developments in psychoanalysis linked some very deep disorders - autistic and symbiotic infantile psychoses, narcissistic personality, and borderline personality disorders – to disturbances in the early development of object relations (Blanck and Blanck 1974 and 1979). As I mentioned earlier, this does not apply to Rankian and Jungian therapists who are aware of the fact that the roots of emotional disorders reach deeper into the psyche.

The above conclusions have been drawn from observations of therapists using primarily verbal means. The understanding of psychogenic disorders changes radically if we employ methods that involve holotropic states of consciousness. These approaches engage levels of the unconscious, which are out of reach of verbal therapy. Initial stages of this work typically uncover relevant traumatic material from early infancy and childhood that is meaningfully related to emotional and psychosomatic problems and appears to be their source, However, when the process of uncovering continues, deeper layers of the unconscious unfold and we find additional roots of the same problems on the perinatal level and even on the transpersonal level of the psyche.

Various avenues of work with holotropic states, such as psychedelic therapy, Holotropic Breathwork, or psychotherapy with people experiencing spontaneous psychospiritual crises, have shown that emotional and psychosomatic problems cannot be adequately explained as resulting exclusively from postnatal sychotraumatic events. The unconscious material associated with them typically forms multilevel dynamic constellations – systems of condensed experience or COEX systems (Grof 1975, 2000). A typical COEX system consists of many layers of unconscious material that share similar emotions or physical sensations; the contributions to a COEX system come from different levels of the psyche. More superficial and easier available layers contain memories of emotional or physical traumas from infancy, childhood, and later life. On a deeper level, each COEX system is typically connected to a certain aspect of the memory of birth, a specific BPM; the choice of this matrix depends on the nature of the emotional and physical feelings involved. If the theme of the COEX system is victimization, this would be BPM II, if it is fight against a powerful adversary or sexual abuse, the connection would be with BPM III, and so on.

The deepest roots of COEX systems underlying emotional and psychosomatic disorders reach into the transpersonal domain of the psyche. They have the form of ancestral, racial, collective, and phylogenetic memories, experiences that seem to be coming from other lifetimes (“past life memories”), and various archetypal motifs. Thus therapeutic work on anger and disposition to violence can, at a certain point, take the form of experiential identification with a tiger or a black panther, the deepest root of serious antisocial behavior can be a demonic archetype, the final resolution of a phobia can come in the form of reliving and integration of a past life experience, and so on.

The overall architecture of the COEX systems can best be shown using a clinical example. A person suffering from psychogenic asthma might discover in serial breathwork sessions a powerful COEX system underlying this disorder. The biographical part of this constellation might consist of a memory of near drowning at the age of seven, memories of being repeatedly strangled by an older brother between the ages of three and four, and a memory of severe whooping cough or diphtheria at the age of two. The perinatal contribution to this COEX would be, for example, suffocation experienced during birth because of strangulation by the umbilical cord twisted around the neck. A typical transpersonal root of this breathing disorder would be an experience of being hanged or strangled in what seems to be a previous lifetime. A detailed discussion of COEX systems, including additional examples appears in several earlier publications (Grof 1975, 1987, and 2000).

Effective Therapeutic Mechanisms

Traditional psychotherapy knows only therapeutic mechanisms operating on the level of the biographical material, such as weakening of the psychological defense

mechanisms, remembering of forgotten or repressed traumatic events, reconstructing the past from dreams or neurotic symptoms, attaining intellectual and emotional insights, analysis of transference, and corrective experience in interpersonal relations. Psychotherapy using holotropic states of consciousness offers many additional highly effective mechanisms of healing and personality transformation, which become available when experiential regression reaches the perinatal and transpersonal levels. Among these are actual reliving of traumatic memories from infancy, childhood, biological birth, and prenatal life, past life memories, emergence of archetypal material, experiences of cosmic unity, and others.

I will illustrate this therapeutic dynamics by the story of a participant in one of our workshops at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California, whom I will call Norbert. At the beginning of the workshop, Norbert complained about severe chronic pain in his left shoulder and pectoral muscle that had caused him great suffering and repeated medical examinations, including X-rays, had not detected any organic basis for his problem and all therapeutic attempts had remained unsuccessful. Serial Procaine injections had brought only brief transient relief for the duration of the pharmacological effect of the drug.

Norbert’s session was long and very dramatic. In the sharing group, he described that there were three different layers in his experience, all of them related to the pain in his shoulder and associated with choking. On the most superficial level, he relived a frightening situation from his childhood in which he almost lost his life. When he was about seven years old, he and his friends were digging a tunnel on a sandy ocean beach. When the tunnel was finished, Norbert crawled inside to explore it. As the other children jumped around, the tunnel collapsed and buried him alive. He almost choked to death before he was rescued by the adults who arrived responding to the children’s alarming screams.

When the breathwork experience deepened, Norbert relived a violent and terrifying episode that took him back to the memory of his biological birth. His delivery was very difficult, since his shoulder was stuck for an extended period of time behind the pubic bone of his mother. This episode shared with the previous one the combination of choking and severe pain in his left shoulder.

In the last part of the session, the experience changed dramatically. Norbert started seeing military uniforms and horses and recognized that he was involved in a fierce battle. He was even able to identify it as one of the battles in Cromwell’s England. At one point, he felt a sharp pain in his left shoulder and realized that it had been pierced by a lance. He fell off the horse and experienced himself as being trampled by the horses running over his body and crushing his chest. His broken rib cage caused him agonizing pain, and he was choking on blood, which was filling his lungs.

After a period of extreme suffering, Norbert’s consciousness separated from his dying body, soared high above the battlefield, and observed the scene from a bird’s eye view. Following the death of the severely wounded soldier, whom he recognized as himself in a previous incarnation, Norbert’s consciousness returned to the present time and reconnected with his body, which was now pain-free for the first time after many years of agony. The relief from pain brought about by these experiences turned out to be permanent.

Strategy of Psychotherapy and Self-Exploration

The most astonishing aspect of modern psychotherapy is the number of competing schools and the lack of agreement among them. They have vast differences of opinion concerning the most fundamental issues, such as: what are the dimensions of the human psyche and what are its most important motivating forces; why do symptoms develop and what they mean; which issues that the client brings into therapy are central and which are less relevant; and, finally, what technique and strategy should be used to correct or improve the emotional, psychosomatic, and interpersonal functioning of the clients.

The goal of traditional psychotherapies is to reach intellectual understanding of the human psyche, in general, and that of a specific client, in particular, and then use this knowledge in developing an effective therapeutic technique and strategy. An important tool in many modern psychotherapies is “interpretation;” it is a way in which the therapist reveals to the client the “true” or “real” meaning of his or her thoughts, emotions, and behavior. This method is widely used in analyzing dreams, neurotic symptoms, behavior, and even seemingly trivial everyday actions, such as slips of the tongue or other small errors, Freud’s “Fehlleistungen” (Freud 1960a). Another area in which interpretations are commonly applied is interpersonal dynamics, including transference of various unconscious feelings and attitudes on the therapist.

Therapists spend much effort trying to determine what is the most fitting interpretation in a given situation and what is the appropriate timing of this interpretation. Even an interpretation that is “correct” in terms of its content, can allegedly be useless or harmful for the patient if it is offered prematurely, before the client is ready for it. A serious flaw of this approach to psychotherapy is that individual therapists, especially those who belong to diverse schools, would attribute very different value to the same psychological manifestation or situation and offer for it diverse and even contradictory interpretations.

This can be illustrated by a humorous example from my psychoanalytic training. As a beginning psychiatrist, I was in training analysis with the nestor of Czechoslovakian psychoananalysis and president of the Czechoslovakian Psychoanalytic Association, Dr. Theodor Dosužkov. It might be of interest to this audience that Dr. Dosužkov was of Russian oeigin and was the student of the famous Russian pioneer of psychoanalysis Nikolai Osipov.

Dr. Dosužkov was in his late sixties and it was known among his analysands - all young psychiatrists - that he had a tendency to occasionally doze-off during analytic hours. Dr.Dosužkov’s habit was a favorite target of jokes of his students. Besides individual sessions of training psychoanalysis, Dr. Dosužkov also conducted seminars, where his students shared reviews of books and articles, discussed case histories, and could ask questions about theory and practice of psychoanalysis. In one of these seminars, a participant asked a “purely theoretical” question: “What happens if during analysis the psychoanalyst falls asleep? If the client continues free-associating, does therapy continue? Is the process interrupted? Should the client get refunded for that time, since money is such an important vehicle in Freudian analysis?”

Dr. Dosužkov could not deny that such a situation could occur in psychoanalytic sessions. He knew that the analysands knew about his foible and he had to come up with an answer. “This can happen,” he said. “Sometimes, you are tired and sleepy – you did not sleep well the night before, you are recovering from a flu, or are physically exhausted. But, if you have been in this business a long time, you develop a kind of “sixth sense;” you fall asleep only when the stuff that is coming up is irrelevant. When the client says something really important, you wake up and you are right there!”

Dr. Dosužkov was also a great admirer of I. P. Pavlov, a Russian Nobel Prize-winning physiologist who derived his knowledge of the brain from his experiments with dogs. Pavlov wrote much about the inhibition of the cerebral cortex that occurs during sleep or hypnosis; he described that sometimes there could be a “waking point” in the inhibited brain cortex. His favorite example was a mother who can sleep through heavy noises, but wakes up immediately when her own child is moaning. “It is just like the situation of the mother Pavlov wrote about,” explained Dr. Dosužkov, “with enough experience, you will be able to maintain connection with your client even when you fall asleep.”

Because of the great conceptual differences between the schools of depth psychology, the question naturally arises which of them has a more correct understanding of the human psyche in health and disease. If it were true that correct and properly timed interpretations are a significant factor in psychotherapy, there would have to be great differences in the therapeutic success achieved by various schools. Their therapeutic results could be mapped on a Gaussian curve; therapists of the school with the most accurate understanding of the psyche and, therefore, most fitting interpretations would have the best results and those belonging to orientations with less accurate conceptual frameworks would be distributed on the descending parts of the curve.

To my knowledge, there are not any scientific studies showing clear superiority of some schools of psychotherapy over others. If anything, the differences are found within the schools rather than between them. In each school there are better therapists and worse therapists. And, very likely, the therapeutic results have very little to do with what the therapists think they are doing – the accuracy and good timing of interpretations, correct analysis of transference, and other specific interventions. Successful therapy probably depends on factors that do not have much to do with intellectual brilliance and are difficult to describe in scientific language, such as the “quality of the human encounter” between therapists and clients or the feeling of the clients that they are unconditionally accepted by another human being, frequently for the first time in their life.

The lack of generally accepted theory of psychotherapy and of basic agreement concerning therapeutic practice is very disconcerting. Under these circumstances, a client who has an emotional or psychosomatic disorder can choose a school by flipping a coin. With each school comes a different explanation of the problem he or she brought into therapy and a different technique is offered as the method of choice to overcome it. Similarly, when a beginning therapist seeking training chooses a particular therapeutic school, it says more about the personality of the applicant than the value of the school.

It is interesting to see how therapy using holotropic states of consciousness can help us to avoid the dilemmas inherent in the above situation. The alternative that this work brings actually confirms some ideas about the therapeutic process first outlined by C. G. Jung. According to Jung, it is impossible to achieve intellectual understanding of the psyche and derive from it a technique that we can use in psychotherapy. As he saw it in his later years, the psyche is not a product of the brain and is not contained in the skull; it is the creative and generative principle of the cosmos (anima mundi). It permeates all of existence and the individual psyche of each of us is teased out of this unfathomable cosmic matrix. The intellect is a partial function of the psyche that can help us orient ourselves in everyday situations. However, it is not in a position to understand and manipulate the psyche.

There is a wonderful passage in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables: "There is one spectacle grander than the sea, that is the sky; there is one spectacle grander than the heavens; that is the interior of the soul." Jung was aware of the fact that the psyche is a profound mystery and approached it with great respect. It was clear to him that the psyche is infinitely creative and cannot be described by a set of formulas that can then be used to correct the psychological processes of the clients. He suggested an alternative strategy for therapy that was significantly different from using intellectual constructs and external interventions.

What a psychotherapist can do, according to Jung, is to create a supportive environment, in which psychospiritual transformation can occur; this container can be compared to the hermetic vessel that makes alchemical processes possible. The next step then is to offer a method that mediates contact between the conscious ego and a higher aspect of the client, the Self. One of Jung’s tools for this purpose was active imagination, continuation of a dream in the analyst’s office (von Franz 1997). The communication between the ego and the Self occurs primarily by means of symbolic

language. In Jung's own words, active imagination is a process of consciously dialoguing with our unconscious "for the production of those contents of the unconscious which lie, as it were, immediately below the threshold of consciousness and, when intensified, are the most likely to erupt spontaneously into the conscious mind." In this kind of work, healing is not the result of brilliant insights and interpretations of the therapist; the therapeutic process is guided from within by the Self.

In Jung’s understanding, the Self is the central archetype in the collective unconscious and its function is to lead the individual toward order, organization, and unity. Jung referred to this movement toward highest unity as the individuation process. The use of holotropic states for therapy and self-exploration essentially confirms Jung’s perspective and follows the same strategy, The facilitators create a protective and supportive environment and help the clients enter a holotropic state. Once that occurs, the healing process is guided from within by the clients’ own inner healing intelligence and the task of the facilitators is to support what is happening. This process automatically activates unconscious material, which has strong emotional charge and is available for processing on the day of the session. This saves the facilitators the hopeless task to sort out what is “relevant” and what is not that plagues verbal therapies. They simply support whatever is spontaneously emerging and manifesting from moment to moment, trusting that the process is guided by intelligence that surpasses the intellectual understanding which can be obtained by professional training in any of the schools of psychotherapy.

.

The Role of Spirituality in Human Life

The leading philosophy of Western science has been monistic materialism. Various scientific disciplines have described the history of the universe as history of developing matter and accept as real only what can be measured and weighed. Life, consciousness, and intelligence are seen as more or less accidental side-products of material processes. Physicists, biologists, and chemists recognize the existence of dimensions of reality that are not accessible to our senses, but only those that are physical in nature and can be revealed and explored with the use of various extensions of our senses, such as microscopes, telescopes, and specially designed recording devices, or laboratory experiments.

In a universe understood this way, there is no place for spirituality of any kind. The existence of God, the idea that there are invisible dimensions of reality inhabited by nonmaterial beings, the possibility of survival of consciousness after death, and the concept of reincarnation and karma have been relegated to fairy tales and handbooks of psychiatry. From a psychiatric perspective to take such things seriously means to be ignorant, unfamiliar with the discoveries of science, superstitious, and subject to primitive magical thinking. If the belief in God or Goddess occurs in intelligent persons, it is seen as an indication that they have not come to terms with infantile images of their parents as omnipotent beings they had created in their infancy and childhood. And direct experiences of spiritual realities are considered manifestations of serious mental diseases – psychoses.

The study of holotropic states has thrown new light on the problem of spirituality and religion. The key to this new understanding is the discovery that in these states it is possible to encounter a rich array of experiences which are very similar to those that inspired the great religions of the world – visions of God and various divine and demonic beings, encounters with discarnate entities, episodes of psychospiritual death and rebirth, visits to Heaven and Hell, past life experiences, and many others. Modern research has shown beyond any doubt that these experiences are not products of pathological processes afflicting the brain, but manifestations of archetypal material from the collective unconscious, and thus normal and essential constituents of the human psyche. Although these mythic elements are accessed intrapsychically, in a process of experiential self-exploration and introspection, they are ontologically real, have objective existence. To distinguish transpersonal experiences from imaginary products of individual fantasy or psychopathology, Jungians refer to this domain as imaginal.

In view of these observations, the fierce battle that religion and science have fought over the last few centuries appears ludicrous and completely unnecessary. Genuine science and authentic religion do not compete for the same territory; they represent two approaches to existence, which are complementary, not competitive. Science studies phenomena in the material world, the realm of the measurable and weighable, spirituality and true religion draw their inspiration from experiential knowledge of the imaginal world as it manifests in holotropic states of consciousness. The conflict that seems to exist between religion and science reflects fundamental misunderstanding of both. As Ken Wilber has pointed out, there cannot possibly be a conflict between science and religion, if both of these fields are properly understood and practiced. If there seems to be a conflict, we are likely dealing with "bogus science" and "bogus religion." The apparent incompatibility is due to the fact that either side seriously misunderstands the other's position and very likely represents also a false version of its own discipline (Wilber 1982).

The only scientific endeavor that can make any relevant and valid judgments about spiritual matters is consciousness research studying holotropic states, since it requires intimate knowledge of the imaginal realm. In his ground-breaking essay, Heaven and Hell, Aldous Huxley suggested that concepts such as Hell and Heaven represent subjective realities experienced in a very convincing way during non-ordinary states of consciousness induced by psychedelic substances, such as LSD and mescaline, or various powerful non-drug techniques (Huxley 1959). The seeming conflict between science and religion is based on the erroneous belief that these abodes of the Beyond are located in the physical universe - Heaven in the interstellar space, Paradise somewhere in a hidden area on the surface of our planet, and Hell in the interior of the earth.

Astronomers have used extremely sophisticated devices, such as the Hubble telescope, to explore and map carefully the entire vault of heaven. Results of these efforts, which have of course failed to find God and heaven replete with harp-playing angels and saints, have been taken as proof that such spiritual realities do not exist. Similarly, in cataloguing and mapping every acre of the planetary surface, explorers and geographers have found many areas of extraordinary natural beauty, but none of them matched the descriptions of Paradises found in spiritual scriptures of various religions. Geologists have discovered that the core of our planet consists of layers of solid and molten nickel and iron, and that its temperature exceeds that of the sun’s surface. This certainly is not a very plausible location for the caves of Satan.

Modern studies of holotropic states have brought strong supportive evidence for Huxley’s insights. They have shown that Heaven, Paradise, and Hell are ontologically real; they represent distinct and important states of consciousness that all human beings can under certain circumstances experience during their lifetime. Celestial, paradisean, and infernal visions are a standard part of the experiential spectrum of psychedelic inner journeys, near-death states, mystical experiences, as well as shamanic initiatory crises and other types of “spiritual emergencies.” Psychiatrists often hear from their patients about experiences of God, Heaven, Hell, archetypal divine and demonic beings, and about psychospiritual death and rebirth. However, because of their inadequate superficial model of the psyche, they misinterpret them as manifestations of mental disease caused by a pathological process of unknown etiology. They do not realize that matrices for these experiences exist in deep recesses of the unconscious psyche of every human being.

An astonishing aspect of transpersonal experiences occurring in holotropic states of various kinds is that their content can be drawn from the mythologies of any culture of the world, including those of which the individual has no intellectual knowledge. C. G. Jung demonstrated this extraordinary fact for mythological experiences occurring in the dreams and psychotic experiences of his patients. On the basis of these observations, he realized that the human psyche has access not only to the Freudian individual unconscious, but also to the collective unconscious, which is a repository of the entire cultural heritage of humanity. Knowledge of comparative mythology is thus more than a matter of personal interest or an academic exercise. It is a very important and useful guide for individuals involved in experiential therapy and self-exploration and an indispensable tool for those who support and accompany them on their journeys (Grof 2006).

The experiences originating on deeper levels of the psyche, in the collective unconscious, have a certain quality that Jung referred to as numinosity. The word numinous is relatively neutral and thus preferable to other similar expressions, such as religious, mystical, magical, holy, or sacred, which have often been used in problematic contexts and are easily misleading. The term numinosity used in relation to transpersonal experiences describes direct perception of their extraordinary nature. They convey a very convincing sense that they belong to a higher order of reality, a realm which is sacred and radically different from the material world.

In view of the ontological reality of the imaginal realm, spirituality is a very important and natural dimension of the human psyche and spiritual quest is a legitimate and fully justified human endeavor. However, it is necessary to emphasize that this applies to genuine spirituality based on personal experience and does not provide support for ideologies and dogmas of organized religions. To prevent misunderstanding and confusion that in the past compromised many similar discussions, it is critical to make a clear distinction between spirituality and religion.

Spirituality involves a special kind of relationship between the individual and the cosmos and is, in its essence, a personal and private affair. By comparison, organized religion is institutionalized group activity that takes place in a designated location, a temple or a church, and involves a system of appointed officials who might or might not have had personal experiences of spiritual realities themselves. Once a religion becomes organized, it often completely loses the connection with its spiritual source and becomes a secular institution that exploits human spiritual needs without

satisfying them.

Organized religions tend to create hierarchical systems focusing on the pursuit of power, control, politics, money, possessions, and other worldly concerns. Under

these circumstances, religious hierarchy as a rule dislikes and discourages direct spiritual experiences in its members, because they foster independence and cannot be effectively controlled. When this is the case, genuine spiritual life continues only in the mystical branches, monastic orders, and ecstatic sects of the religions involved. People who have experiences of the immanent or transcendent divine open up to spirituality found in the mystical branches of the great religions of the world or in their monastic orders, not necessarily in their mainstream organizations. A deep mystical experience tends to dissolve the boundaries between religions and reveals deep connections between them, while dogmatism of organized religions tends to emphasize differences between various creeds and engender antagonism and hostility.

There is no doubt that the dogmas of organized religions are generally in fundamental conflict with science, whether this science uses the mechanistic-materialistic model or is anchored in the emerging paradigm. However, the situation is very different in regard to authentic mysticism based on spiritual experiences. The great mystical traditions have amassed extensive knowledge about human consciousness and about the spiritual realms in a way that is similar to the method that scientists use in acquiring knowledge about the material world. It involves methodology for inducing transpersonal experiences, systematic collection of data, and intersubjective validation.

Spiritual experiences, like any other aspect of reality, can be subjected to careful open-minded research and studied scientifically. There is nothing unscientific about unbiased and rigorous study of transpersonal phenomena and of the challenges they present for materialistic understanding of the world. Only such an approach can answer the critical question about the ontological status of mystical experiences: Do they reveal deep truth about some basic aspects of existence, as maintained by various systems of perennial philosophy, or are they products of superstition, fantasy, or mental disease, as Western materialistic science sees them?

Western psychiatry makes no distinction between a mystical experience and a psychotic experience and sees both as manifestations of mental disease. In its rejection of religion, it does not differentiate between primitive folk beliefs or the fundamentalist literal interpretations of religious scriptures and sophisticated mystical traditions or the great Eastern spiritual philosophies based on centuries of systematic introspective exploration of the psyche. Modern consciousness research has brought convincing evidence for the objective existence of the imaginal realm and has thus validated the main metaphysical assumptions of the mystical world view, of the Eastern spiritual philosophies, and even certain beliefs of native cultures.

The Importance of Archetypal Psychology and Transit Astrology

The greatest surprise I have experienced during the fifty some years I have been involved in consciousness research was the discovery of the extraordinary predictive power of astrology. Because of my strict scientific training, my skepticism concerning astrology was very strong and persistent. The idea that stars could have anything to do with states of consciousness, let alone events in the world, seemed too absurd and preposterous to be taken seriously. It took years and thousands of convincing observations to accept this possibility; it required nothing less than a radical revision of my basic metaphysical assumptions about the nature of reality. Since I am aware how controversial and charged this issue is, I do not think I would have included astrology in my today’s presentation, if it were not for the fact that Richard Tarnas is with us at this conference and interested participants will have the chance to attend his seminar and judge for themselves the seriousness of his ground-breaking meticulous research. And I understand that the Russian translation of his seminal work, Cosmos and Psyche (Tarnas 2006) is now available in Russian translation.

Over the last thirty years, Rick and I have jointly explored astrological correlations of holotropic states. My main task has been to collect interesting clinical observations from psychedelic sessions, Holotropic Breathwork workshops and training, mystical experiences, spiritual emergencies, and psychotic breaks. Rick’s main focus has been on astrological aspects of holotropic states of consciousness. This cooperation has brought convincing evidence that there exist systematic correlations between the nature, timing, and content of holotropic states of consciousness and planetary transits of the individuals involved.

The first indication that there might be some extraordinary connection between astrology and my research of holotropic states was the realization that my description of the phenomenology of the four basic perinatal matrices (BPMs), experiential patterns associated with the stages of biological birth, showed astonishing similarity to the four archetypes that astrologers link to the four outer planets of the solar system – BPM I to Neptune, BPM II to Saturn, BPM III to Pluto, and BPM IV to Uranus. It is important to emphasize that my description of the phenomenology of the BPMs was based on clinical observations made quite independently many years before I knew anything about astrology.

Even more astonishing was the discovery that in holotropic states the experiential confrontation with these matrices regularly occurs at the time when the individuals involved have important transits of the corresponding planets. Over the years, we have been able to confirm this fact by thousands of specific observations and discover further astrological correlations for many other aspects of holotropic states. Because of these surprisingly precise correlations, astrology, particularly transit astrology, turned out to be the long-sought Rosetta stone of consciousness research, providing a key for understanding the nature and content of present, past, and future holotropic states, both spontaneous and induced. I believe now that responsible work with holotropic states combined with archetypal psychology and using transit astrology as guide represents the most promising trend in psychotherapy.

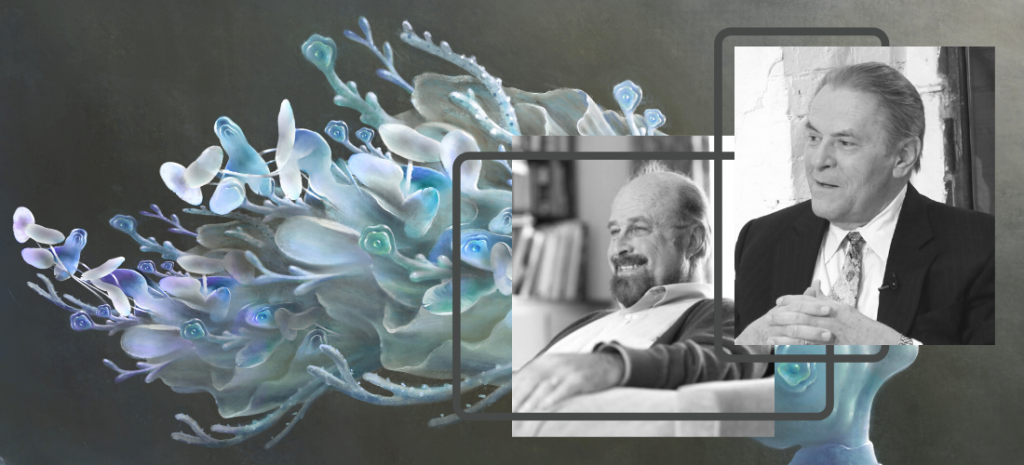

Observations from 4000 LSD Sessions: A Dialogue with Stanislav Grof by Dr. Richard Louis Miller, MA, PhD | Reality Sandwich Dr. Richard Louis Miller, MA, PhD: You started out as a psychiatrist doing Freudian work. You were initially deeply interested in psychoanalysis, but then something...

www.bluelight.org