Psychedelics, Meditation, and Self-Consciousness / Part 1

Raphaël Millière, Robin Carhart-Harris, Leor Roseman, Fynn-Mathis Trautwein, Aviva Berkovich-Ohana | Frontiers In Psychology | 4 Sep 2018

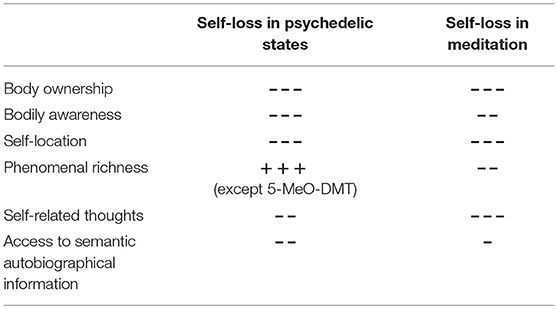

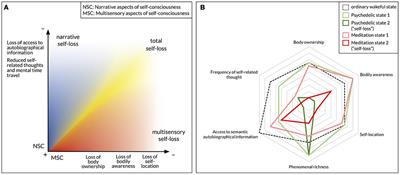

In recent years, the scientific study of meditation and psychedelic drugs has seen remarkable developments. The increased focus on meditation in cognitive neuroscience has led to a cross-cultural classification of standard meditation styles validated by functional and structural neuroanatomical data. Meanwhile, the renaissance of psychedelic research has shed light on the neurophysiology of altered states of consciousness induced by classical psychedelics, such as psilocybin and LSD, whose effects are mainly mediated by agonism of serotonin receptors. Few attempts have been made at bridging these two domains of inquiry, despite intriguing evidence of overlap between the phenomenology and neurophysiology of meditation practice and psychedelic states. In particular, many contemplative traditions explicitly aim at dissolving the sense of self by eliciting altered states of consciousness through meditation, while classical psychedelics are known to produce significant disruptions of self-consciousness, a phenomenon known as drug-induced ego dissolution. In this article, we discuss available evidence regarding convergences and differences between phenomenological and neurophysiological data on meditation practice and psychedelic drug-induced states, with a particular emphasis on alterations of self-experience. While both meditation and psychedelics may disrupt self-consciousness and underlying neural processes, we emphasize that neither meditation nor psychedelic states can be conceived as simple, uniform categories. Moreover, we suggest that there are important phenomenological differences even between conscious states described as experiences of self-loss. As a result, we propose that self-consciousness may be best construed as a multidimensional construct, and that “self-loss,” far from being an unequivocal phenomenon, can take several forms. Indeed, various aspects of self-consciousness, including narrative aspects linked to autobiographical memory, self-related thoughts and mental time travel, and embodied aspects rooted in multisensory processes, may be differently affected by psychedelics and meditation practices. Finally, we consider long-term outcomes of experiences of self-loss induced by meditation and psychedelics on individual traits and prosocial behavior. We call for caution regarding the problematic conflation of temporary states of self-loss with “selflessness” as a behavioral or social trait, although there is preliminary evidence that correlations between short-term experiences of self-loss and long-term trait alterations may exist.

Introduction

The scientific study of meditation and psychedelic drugs has seen remarkable developments in recent years. The increased focus on meditation in cognitive neuroscience has led to a cross-cultural classification of standard meditation styles validated by functional and structural neuroanatomical data. Meanwhile, the renaissance of psychedelic research has shed light on the neurophysiology of altered states of consciousness induced by classical hallucinogens, such as psilocybin and LSD, whose effects are mainly mediated by agonism of serotonin receptors, and the serotonin 2A receptor subtype specifically. However, few attempts have been made at bridging these two domains of inquiry, despite increasing evidence of overlap between the phenomenology and neurophysiology of meditation practices and psychedelic states.

In particular, many contemplative traditions explicitly aim at dissolving the sense of self by eliciting altered states of consciousness through meditation, while classical psychedelics are known to produce significant disruptions of self-consciousness, a phenomenon known as “drug-induced ego dissolution." In this article, we discuss available evidence regarding convergences and differences between phenomenological and neurophysiological data on meditation practice and psychedelic drug-induced states, with a particular emphasis on alterations of self-experience. While both meditation and psychedelics are suspected to disrupt self-consciousness and its underlying neural processes, this general hypothesis requires careful qualification.

First, it is important to emphasize right away that neither meditation nor psychedelic states can be conceived as simple, uniform categories. Many variables modulate the subjective effects of contemplative practice and psychedelics, including the style of meditation or the drug and dosage used, as well as personal factors such as level of experience and personality traits. In particular, dramatic disruptions of self-consciousness seem to occur mostly for highly experienced meditators or with high doses of psychedelics. Thus, we suggest that both meditation and psychedelics can induce a wide variety of global states of consciousness, but these states are sensitive to a multitude of factors in addition to the specific inducers we are highlighting here.

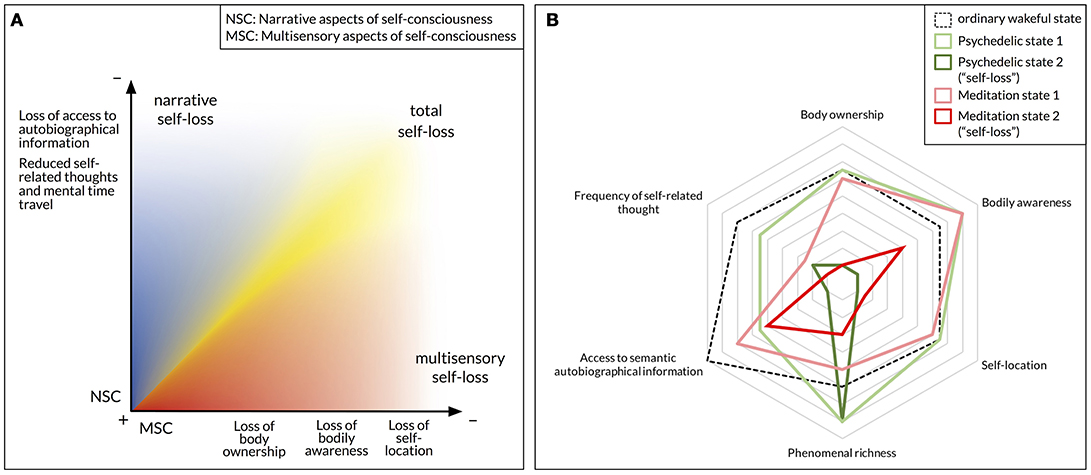

In addition, we suggest that there are important phenomenological differences even between conscious states described as experiences of self-loss. As a result, we propose that self-consciousness may be best construed as a multidimensional construct, and that “self-loss” or “ego dissolution,” far from being an unequivocal phenomenon, can take several forms. Indeed, various aspects of self-consciousness, including narrative aspects linked to autobiographical memory, self-related thoughts and mental time travel, and embodied aspects rooted in multisensory processes, may be differently affected by psychedelics and meditation practices. It is also worth acknowledging that “self-loss” or “ego dissolution” may be a non-linear phenomenon that only occurs after a critical inflection point has been reached.

Finally, we consider long-term outcomes of experiences of self-loss induced by meditation and psychedelics on individual traits and prosocial behavior. We call for caution regarding the problematic conflation of temporary states of self-loss with “selflessness” as a personal or social trait, although it remains possible that correlations exist between short-term experiences and long-term dispositions in this regard.

The neuroscience of meditation and psychedelics: An overview

Meditation refers to a set of cognitive training techniques and practices that aim to monitor and regulate attention, perception, emotion and homeostasis (e.g., breathing rate). Such techniques and practices have been developed in many different cultures and spiritual traditions, yielding more than a 100 varieties of meditation. Most scientific research on the topic has focused on techniques originating in the Buddhist tradition from China, Tibet, India and Southeast Asia, with a particular focus on practices often subsumed under the loose category of mindfulness meditation. Nonetheless, there are a growing number of studies on meditative practices from other contemplative traditions – including yogic, Hindu, Christian, Sufi, shamanic and transcendental practices.

Box 1. Glossary.

Drug-induced Ego Dissolution (DIED). A family of acute effects produced by high doses of psychedelic drugs, typically reported as a loss of one's sense of self and self-world boundary.

Focused Attention (FA). A common style of meditation that involves sustaining one's attentional focus on a particular object, either internal (e.g., breathing) or external (e.g., a candle flame). The practitioner is instructed to monitor their attention, notice episodes of distraction (mind-wandering), and bring their attention back to the object. FA is usually the starting point for novice meditators.

Loving-Kindness Meditation (LK). A common style of meditation that focuses on developing compassion and love for oneself and others, gradually extending the focus of empathy to foreign and disliked individuals or even all living-beings. While loving-kindness meditation incorporates technical elements from FA and open monitoring (OM, defined below), it has a distinct phenomenology and neural correlates due to its emotional content.

Mantra Recitation (MR). A style of meditation that involves repeating a sound, word or sentence, either aloud or in one's mind, in order to calm the mind and avoid mind-wandering. Although MR is arguably a form of Focused Attention meditation, it is distinguished by its speech component and may have distinct neural correlates.

Meta-Awareness. The ability to take note of the content of one's current mental state. In the context of meditative practices, meta-awareness often refers specifically to the meditator's awareness of episodes of mind-wandering (spontaneous thoughts arising during meditation).

Mindfulness Meditation. A group of practices aimed at cultivating mindfulness, typically defined as a state of non-judgmental awareness to one's present moment experience. Mindfulness meditation may refer to both focused attention (FA) and open monitoring (OM) practices.

Non-Dual Awareness (NDA). In many contemplative traditions (including Advaita Vedanta and Kashmiri Shaivism within Hinduism, and Dzogchen and Mahāmudrā within Buddhism), the practice of meditation aims at recognizing the illusory nature of the subject-object dichotomy that allegedly structures ordinary conscious experience, thus revealing the “non-dual awareness” that lies at the background of consciousness.

Open Monitoring (OM). A common style of meditation that aims at bringing attention to the present moment and openly observing mental contents without getting caught up in focusing on any of them. Open monitoring meditation traditionally follows focused awareness, as the practitioner learns to switch from a narrow attentional focus on an object to a global awareness of the present moment.

Psychedelic Drugs. A family of psychoactive compounds whose complex effects on the quality of conscious experience are mainly mediated by their action on serotonin receptors in the brain (and specifically their binding to and stimulation of serotonin 2A receptor subtype). Psychedelic substances include mescaline, psilocybin (so-called “magic mushrooms”), Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD), N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), and the DMT-containing brew Ayahuasca.

Pure Consciousness (PC). A state of consciousness described as “objectless” or entirely devoid of phenomenal content. While the possibility of such states is very controversial, certain conscious states induced by some meditative practices and classical psychedelics might lack at least

ordinary phenomenal content. In the Hindu and Buddhist traditions, the practice of

Samadhi is often described as leading to the experience of PC.

To address this remarkable diversity of traditions, researchers have also sought to categorize the main styles of meditation across cultural, geographical and historical contexts, based on the core goals and principles of the mental techniques involved. Common styles of meditation include focused attention meditation (FA)—which requires sustaining one's attention on a particular object or sensation such as the breath—, open monitoring meditation (OM)—which involves a non-judgmental, non-selective awareness of the present moment—, loving-kindness and compassion meditation (LK)—which involves the cultivation of compassion toward oneself and others—, and mantra recitation (MR)—which involves the repetition of a sound, word or sentence (see Box 1). The subjective effects of meditation are multifaceted, including enhanced attention and sensory processing, largely positive emotions and mood, increased cognitive flexibility and creativity, and, in some cases (usually with increasing expertise) dramatic disruptions of one's sense of self.

Classic psychedelics, also known as classic hallucinogens, are a family of psychoactive substances that exert their subjective effects primarily by agonism (or partial agonism) of serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) receptors. Psychedelics include molecules found in the natural world such as psilocybin (a prodrug of psilocin found in so-called “magic mushrooms”), mescaline (found in various South American cacti, including Peyote, San Pedro and Peruvian torch), N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT, found in many plants such as

Mimosa tenuiflora, Diplopterys cabrerana, and

Psychotria viridis, and used in combination with monoamine oxidase inhibitors in the shamanic brew Ayahuasca) and 5-MeO-DMT (found in the toxin of the toad

Bufo alvarius, as well as a wide variety of plants such as

Anadenanthera peregrina used in yopo snuff). Psychedelics also include many synthetic compounds, such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and phenethylamines of the 2C-

x family (e.g., 2C-B). The subjective effects of psychedelics are complex and multifaceted, including visual and auditory distortions and complex closed-eye “visions,” profound changes in emotions and mood, heightened sensitivity to internal and external context, and at higher doses, dramatic alterations of self-consciousness known as drug-induced ego dissolution (DIED).

Neural correlates of meditative practices

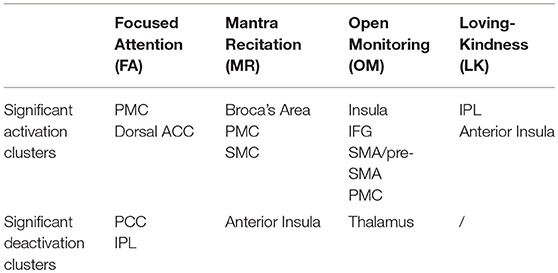

Over the past 20 years, a large number of neuroimaging studies have investigated various styles of meditation, using electro-encephalography (EEG), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) to measure changes in blood flow and electrical activity in the brain during meditation. This research program seeking to isolate the neural correlates of various meditation practices has come to be known as contemplative neuroscience. Interestingly, the wealth of data collected from these studies has begun to reveal that meditation practices from distinct traditions relying on similar mental techniques, also share some common neural correlates. A recent meta-analysis of 78 functional neuroimaging studies of meditation found dissociable patterns of activation and deactivation for four common styles of meditation: focused attention (FA), mantra recitation (MR), open monitoring (OM), and loving-kindness meditation (LK).

Table 1. Significant clusters of activation/deactivation in four common meditation

styles from a meta-analysis of 78 neuroimaging studies (

Fox et al., 2016).

FA was correlated with significant activation clusters in executive brain areas such as the premotor cortex and the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, which may underlie top-down regulation of attention and monitoring of spontaneous thoughts. FA was also correlated with the deactivation of two important hubs of the so-called default-mode network (DMN) namely, the posterior cingulate cortex and inferior parietal lobule, involved in a plethora of introspection-related functions including self-reflection, mind-wandering, autobiographical memory recollection, mental time travel to the future and imagination more broadly. The main clusters of activation for MR were found in the motor control network (Broca's area, premotor cortex and supplementary motor cortex) and the putamen. The involvement of these regions in speech production and attention regulation is consistent with the practice of mantra recitation, which relies on the constant repetition of a phrase either in one's mind or out loud. MR was also associated with a significant deactivation cluster in the anterior insula, suggesting that the focus on a repeated phrase is linked to decreased awareness of bodily sensation.

By contrast, OM was found to be correlated with activation clusters in the insular cortex, involved in awareness of interoceptive signals, as well as in brain regions associated with the voluntary control of thought and action, such as the left inferior frontal gyrus, the pre-supplementary and supplementary motor areas, and the premotor cortex. OM was also associated with the deactivation of the right thalamus, a region involved in filtering out sensory stimuli (sensory gating), suggesting that the increased focus of awareness during OM is mediated by decreased sensory gating. Finally, significant activation clusters for LK were found in the right somatosensory cortices, the inferior parietal lobule and the right anterior insula, while no significant deactivation cluster was found. Although these four meditation styles are clearly dissociated by their neural correlates, Fox and colleagues found a few recurrent patterns of activity modulation, in particular in the insular cortex, an important multisensory area heavily involved in interoceptive awareness.

It is worth noting that distinct styles of meditation were found to modulate the activity of the insula in different ways, namely activation for FA, OM, and LK, and deactivation for MR. Nonetheless, the involvement of the insula in all four styles of meditation points toward the central role of the attentional control of bodily awareness, and awareness of breathing in particular, during various contemplative practices. Other convergent patterns of activity were found to a lesser extent in regions involved in the regulation of attention such as the premotor cortex, supplementary motor area and dorsal cingulate cortex.

Importantly, and albeit not emphasized by, attenuation of either activity or functional connectivity in the default mode network (DMN), a large-scale intrinsic network which is highly active at rest but less active during goal-directed tasks, was shown for MR, and in many studies of mindfulness meditation (combining FA and OM in different degrees). These studies reported a decrease of activity in key nodes of the DMN, particularly in the medial prefrontal cortex and in the posterior cingulate cortex, compared to meditation-naïve controls or within-group resting state. While DMN deactivation is not specific to mindfulness meditation, it has been found to be more pronounced during meditation than during other cognitive tasks. Moreover, several studies reported altered connectivity during different types of meditation most consistently in association with the DMN. Specifically, within-DMN connectivity was found to be reduced during LK.

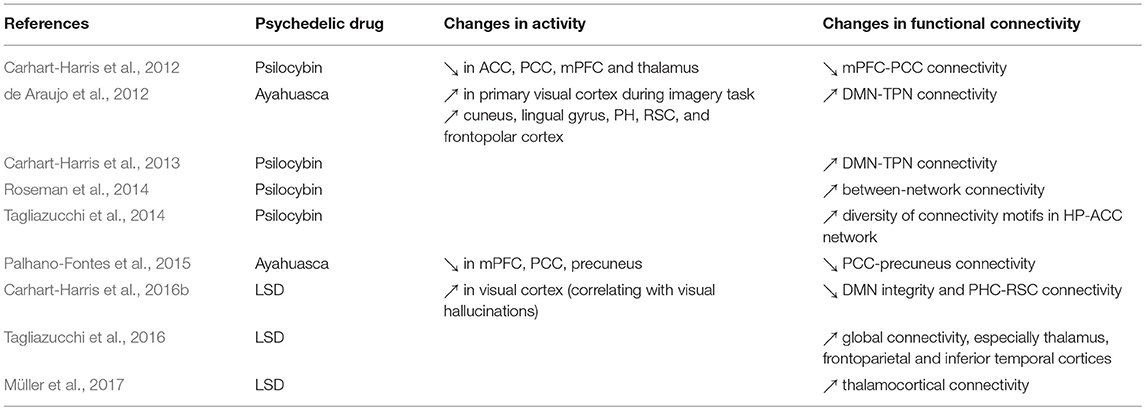

Neural correlates of psychedelic states

Recent years have seen a renaissance of scientific research on psychedelic drugs, using modern neuroimaging techniques to gather insight into the neural correlates of their vivid subjective effects. Early neuroimaging studies using PET and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) after administration of psilocybin and mescaline found excitatory effects on frontal cortical areas, medial temporal lobes and the amygdala. By contrast, recent fMRI of psilocybin and ayahuasca found significant

reductions in activity across many brain areas, including frontal and temporal cortical regions, as well as hubs of the DMN. This apparent discrepancy could be due to the much greater timescales used by PET/SPECT compared to fMRI.

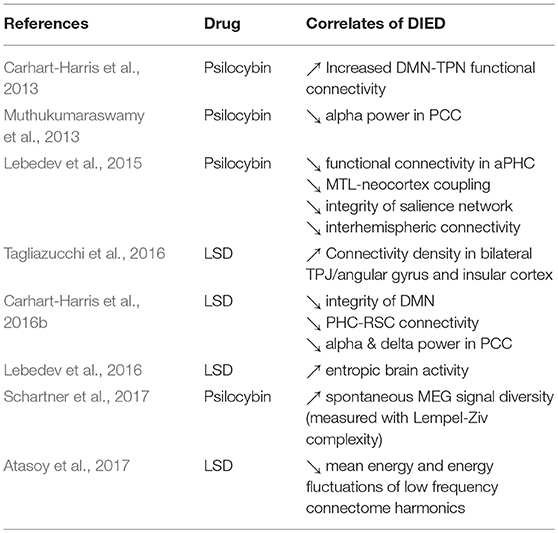

Table 2. Main changes in activity and connectivity in the psychedelic state.

Recent fMRI studies also revealed alterations of resting-state functional connectivity in key nodes of the DMN after administration of psilocybin, ayahuasca and LSD. Researchers found increased integration between cortical regions under ayahuasca, psilocybin, and LSD. Finally, psilocybin and LSD were found to produce an enhanced repertoire of dynamical brain states and increased spontaneous MEG signal diversity.

Psychedelic drugs are known to produce short-term, dramatic effects on self-consciousness, especially at higher doses. This phenomenon is known as drug-induced ego dissolution (DIED); it is described a loss of one's sense of self and self-world boundaries, together with a concomitant oceanic feeling of “oneness” or “unity." Such effects on self-consciousness had already been reported in early studies with mescaline, LSD and psilocybin. Recent studies have sought to investigate the neural correlates of DIED, using correlations between questionnaire items and neuroimaging data. The main correlates of DIED, summarized in Table

3, include increased functional connectivity between the DMN and a task-positive network, decreased integrity of the DMN (i.e., decreased within network correlation of timecourses) and salience network, decreased connectivity between the parahippocampal and retrosplenial cortices, increased entropic brain activity and spontaneous MEG signal diversity, and decreased mean energy and fluctuations of low frequency connectome harmonics.

Table 3. Neural correlates of drug-induced ego dissolution (DIED).

Alterations of self-consciousness induced by meditation and psychedelics

While it is often claimed that meditation and psychedelic drugs are both able to induce “selfless” states of consciousness, that is conscious states entirely lacking a sense of self, this statement requires qualification. Indeed, “self-loss” and related expressions such as “ego dissolution” are notoriously ambiguous notions. Self-consciousness itself may be best construed as a multidimensional construct including somatosensory, agentive, narrative and social components. A conscious state in which one of these aspects is radically disrupted may be described as “selfless” in one respect, although a subject undergoing such a state could retain other forms of self-consciousness. Therefore, it is important to investigate which aspect(s) of self-consciousness can be disrupted by meditation and psychedelics, and whether both modes of induction may alter self-consciousness in similar ways. In addition, there is a further question regarding the possibility of truly “selfless” states, namely conscious mental states lacking

any kind of self-consciousness. While some meditative practices and psychedelic drugs have been hypothesized to produce such “selfless” states, this claim needs to be supported by an examination of phenomenological reports in light of the distinction between different aspects of self-consciousness. In this section, we discuss the ways in which meditation and psychedelics may disrupt narrative, agentive and somatosensory aspects of self-consciousness, either in isolation or in combination. Moreover, we critically examine theoretical discussions and self-reports about states of “non-dual awareness” and “pure consciousness” allegedly induced by meditation.

Disruption of narrative aspects of self-consciousness

The familiar experience of thinking about oneself is perhaps the most salient form of self-consciousness. In philosophy of mind, this is also known as having

de se thoughts, namely thoughts that involve the first-person concept and are naturally expressed using the first-person pronoun.

De se thoughts themselves come in different flavors, which are more or less egocentric. Thus, one may explicitly reflect on one's personality traits or one's life trajectory, both of which are important elements of an individual's identity. This category of

de se thought broadly pertains to the entertainment of core self-related beliefs, and is often linked to the notion of narrative selfhood—the stories we tell ourselves about the kind of person we are or want to be. Admittedly, this kind of

de se thought only occurs sporadically in the waking state, because we are not constantly reflecting on our personal identity. However,

de se thoughts also include more mundane and pervasive instances of mind-wandering, such as wondering what one will have for dinner. Such thoughts also link back to the self, insofar as they engage the first-person concept, even if they are not directly related to fundamental beliefs about one's identity. More generally, this family of self-referential cognitive content includes not only

de se thoughts about the present moment, but also autobiographical memory retrieval and self-centered mental time travel to the future, both of which also crucially involve the self. Together, these self-referential mental episodes constitute what may be called narrative self-consciousness, namely the complex sequences of self-centered thoughts, memories and imaginings that weave the narrative of our daily lives and shape our core self-related beliefs.

There are at least two ways in which narrative self-consciousness may be disrupted. First, the rate of occurrence of self-referential thought and mental time travel may be dramatically reduced, or altogether suppressed, during a certain time interval. There is convincing evidence from experience sampling studies that mind-wandering and mental time travel is more ubiquitous in the waking state than we might think, due to the fact that we are often unaware of such episodes. Moreover, daily mind-wandering episodes are predominantly future-focused, and frequently involve the planning and anticipation of personal goals, known as autobiographical planning. Thus, it is not exaggerated to say that a large part of our lives is spent entertaining self-involving thoughts, insofar as this includes spontaneous

de se thoughts about the future. Most contemplative practices, especially in the Buddhist tradition, explicitly aim at increasing meta-awareness of mind-wandering, namely monitoring and taking explicit note of spontaneous thoughts, in order to disengage from them and re-focus attention back onto a particular object (such as the breath or a mantra) or on a wider awareness of the present moment. Once attention has been stabilized and the mind “quieted,” meditators can undergo prolonged conscious episodes entirely lacking in self-referential thoughts

3.

This is consistent with the neurophysiological basis of mindfulness meditation reviewed in the previous section. While key nodes of the DMN such as the mPFC and the PCC are especially active during mind-wandering, a number of studies have found that these regions are deactivated during mindfulness meditation—which is consistent with the practice's focus on attentional control of mind-wandering episodes. Importantly, the decrease in DMN activity is more significant during meditation than during other cognitive tasks, which speaks to the crucial issue of specificity and may be characteristic of the suppression of mind-wandering that can be achieved by trained meditators. It is also worth noting that experiences of flow, namely states of intense focus in which self-referential processing is inhibited (such as intense practice in expert athletes or jazz improvisation in expert musicians), are also associated with decreased activity in the mPFC. Interestingly, psychedelic drugs have been shown to decrease activity in the mPFC and PCC as well. These nodes of the DMN have been shown to be more active during various types of self-related stimuli, self-reflection and autobiographical memory retrieval. A recent study using dynamic causal modeling suggested that self-referential processes are driven by PCC activity and modulated by the regulatory influences of the mPFC.

Aside from changes in cerebral blood flow in these regions, psilocybin, ayahuasca and LSD have also been consistently linked to decreased functional integrity of the DMN. Moreover, DMN disintegration was correlated with reports of ego dissolution and decreased mental time travel to the past. These findings are intriguing, because strong DMN connectivity at rest is associated with increased tendency for mental time travel, in particular spontaneous thoughts about the future. This suggests that reports of drug-induced ego dissolution may be related to the experience of decreased self-referential thought and mental time travel, which is also fundamental to the practice of meditation.

While the temporary cessation of self-referential thoughts is one way in which narrative self-consciousness may be altered, it may also be disrupted by a total loss of access to autobiographical memories and self-related beliefs. These two cases are not unrelated, given that the unavailability of personal memories and beliefs precludes the possibility of at least some forms of

de se thought and mental time travel. However, the experience of losing access to these memories and beliefs might differ from the mere cessation of

de se thought from a phenomenological point of view. Indeed, anecdotal evidence from narrative self-reports suggests that drug-induced ego dissolution may be related in some cases to reversible retrograde amnesia, specifically regarding abstract information about oneself (i.e., semantic autobiographical memory). For example, one subject responding to an online questionnaire on ego dissolution reported “

forgetting that I was a male, a human, a being on Earth—all gone, just infinite sensations and visions,” while another stated

“I no longer felt human. I didn't remember what a human was” (R.M., unpublished data from an online survey on drug-induced ego dissolution completed by experienced users of psychedelic drugs).

Interestingly, decreased functional connectivity within the DMN is associated with age-related memory deficits and Alzheimer's disease. Given the link between DMN disintegration (decreased within-network connectivity) and ego dissolution, it is intriguing to speculate that the temporary loss of access to semantic autobiographical information that can occur in the psychedelic state may be mediated by pronounced reductions in DMN integrity. Interestingly,

post-hoc mediation analyses from Dillen and colleagues revealed that the retrosplenial cortex enables communication between the hippocampus and DMN regions in healthy controls, but not in individuals reporting cognitive decline or diagnosed with prodromal Alzheimer's disease. Ratings of ego dissolution under LSD have been shown to correlate with decreased resting-state functional connectivity between the retrosplenial cortex and the parahippocampu. If the retrosplenial cortex acts as a gateway between the hippocampal formation and specific DMN regions for memory retrieval, the correlation between this change in connectivity and ego dissolution may be related to a loss of access to autobiographical memories. It is also interesting to note that damage to the retrosplenial cortex has been linked with retrograde amnesia, and damage to the hippocampal formation has been associated with both retrograde amnesia and loss of general world knowledge.

In summary, narrative aspects of self-consciousness can be radically altered during a specific conscious episode in two ways: through a temporary cessation of self-referential thought and mental time travel, or more dramatically through a temporary loss of access to semantic autobiographical information, resulting in a complete breakdown of one's personal identity. While the former can seemingly be induced both by contemplative practices and by psychedelic drugs, the latter appears to be more specific to psychedelics, and may be related to more pronounced reductions in DMN integrity—which does not appear to be such a reliable feature of meditation.

In the first case, the retrieval of self-related information is effectively reduced, via attentional control in the case of meditation, and perhaps via an involuntary attentional shift in the case of psychedelic states. In the second case, even the dispositional ability to retrieve such information is temporarily impaired, which amounts to a form of reversible amnesia. It is important to note that these alterations of narrative aspects of self-consciousness come in degrees. At low doses of psychedelics or in novice meditators, self-referential spontaneous thoughts and mental time travel are unlikely to disappear entirely for an extended period of time. By contrast, states of deep absorption achieved by advanced meditators or with higher doses of psychedelics are more likely to involve a complete cessation of these thoughts. Similarly, the disruption of

access to self-related information may be partial or total in different cases. For example, there is a difference between the inability to remember what one has done the day before, the inability to remember one's name, and the inability to remember anything at all about oneself, including that one belongs to the human species (which has been reported,

post-hoc, with certain doses of some psychedelics). Thus, narrative aspects of self-consciousness may be temporarily disrupted in different ways and to varying degrees by meditation and psychedelics and it is not yet clear whether these different degrees or grades lie on a linear or nonlinear scale.

Disruption of multisensory aspects of self-consciousness

While self-related thoughts are a paradigmatic example of self-consciousness, it is widely agreed that self-consciousness is not strictly limited to the cognitive domain. In particular, a number of authors have stressed the need to distinguish between the “narrative self,” congruent with narrative aspects of self-consciousness outlined in the previous section, and the “minimal” or “embodied” self. For example, Gallagher defines the minimal self as

“a consciousness of oneself as an immediate subject of experience, unextended in time,” by opposition with the temporal thickness of the narrative self-woven by autobiographical memories and self-projection to the future. Moreover, many authors have insisted on the idea that the minimal self is crucially linked to embodiment and agency, equating this basic form of self-consciousness with an awareness of oneself as an embodied agent. While the distinction between high-level/narrative and minimal/embodied selfhood is helpful as a first pass to clarify the umbrella notion of self-consciousness, it remains somewhat ambiguous and potentially simplistic as such. As we have seen, the “narrative self” is better construed as a family of distinct self-referential processes, which may or may not involve mental time travel, be spontaneous, or recruit abstract semantic information. Likewise, the “embodied” or “minimal” self may be construed as a complex set of somatosensory and agentive aspects of self-consciousness which can come apart in special cases

At least three constructs that have been related to a basic form of self-consciousness rooted in multisensory processing may be distinguished, namely: (a) the sense of body ownership, namely the alleged sense of “mineness” that one experiences with respect to one's own body or individual limbs; (b) bodily awareness in general, namely the awareness of any bodily sensation, either internal (interoception and proprioception) or external (tactile); and (c) spatial self-location, namely the experience of being located somewhere in space with respect to one's perceived environment.

The sense of body ownership

Body ownership is a controversial notion, as it is not obvious that there is a phenomenology of ownership (a sense of “mineness” over one's body) in daily experience, or how to characterize such phenomenology. Clinical and experimental evidence suggests that individuals may see body parts or feel tactile sensations originating from them without experiencing them as their own. Indeed, subjects diagnosed with the monothematic delusion known as somatoparaphrenia routinely deny ownership of a limb, despite the fact that nociception and touch may be preserved in the rejected body part. In the rubber hand illusion, one of the subjects' hands is hidden and stroked synchronously with a rubber hand placed in an anatomically congruent position in front of them; not only do healthy participants report experiencing an illusory ownership over the fake hand, but they also report a loss of ownership over their real hand. Moreover, a number of physiological measurements appear to indicate that the real limb is temporarily ‘disowned' by the body during the illusion, such as a drop in temperature and an increase in histamine reactivity in the participant's real hand. Beyond individual body parts, questionnaire data suggest that ownership over one's

whole body can be manipulated in so-called full-body illusions induced by synchronous visuotactile stimulation, during which the participant's body—seen in front of them through a head-mounted display—may no longer feel like their own.

Although still a matter of controversy, many authors interpret these data as evidence that ordinary conscious experience involves a sense of body ownership that can both be experimentally manipulated and disrupted in clinical cases. Experiencing one's body as one's own would constitute a form of self-consciousness that does not require the possession or deployment of a self-concept, unlike thinking of oneself. Assuming that such a sense of body ownership is indeed ubiquitous at least in the ordinary experience of neurotypical individuals, is there any evidence that it can be altered by meditation and psychedelics? Interestingly, recent studies by Aviva Berkovich-Ohana and colleagues suggest that mindfulness meditation can indeed induce a loss of body ownership. Ataria and colleagues studied a single highly experienced meditator “S” (with around 20,000 h of practice) trained in the Satipathana and Theravada Vipassana traditions, who was reportedly able to voluntarily induce a state in which basic aspects of self-consciousness appeared to fade away. In particular, S described the dissolution of the sense of body ownership in a series of open-ended interviews following the methodological principles of the microphenomenological interview technique, designed to elicit fine-grained reports of subjective experience while minimizing potential for confabulation. S reported that in the altered state of consciousness he achieved through meditation

“there really isn't any [sense of ownership]. It's a feeling of dissolving. [It is] hard to distinguish between senses in the body and senses outside [sic]… There is no sense of mine [and] there is no sense of me." While evidence from single-subject studies should be treated as tentative and interpreted with caution, Dor-Ziderman and colleagues also tested 12 long-term mindfulness meditators in a neurophenomenological study combining magnetoencephalogram (MEG) recording and first-person reports. Participants were instructed to voluntarily induce a “selfless” mode of awareness characterized as

“momentary phenomenal experience free of the sense of agency and ownership." Subjective reports were analyzed and grouped in categories validated by 12 naïve referees. Four reports were grouped in the category of experiences lacking a sense of ownership, including the following descriptions:

“I understood that it was just a sensation, it was not the hand itself… there was a deep thought that all this was not mine” (subject 9);

“it was emptiness, as if the self-fell out of the picture. There was an experience but it had no address, it was not attached to a center or subject” (subject 12);

“it was to be aware of the body, the sensations, pulse, location of limbs, sounds and sights—to be only a witness to all this” (subject 14).

There are also many reports of depersonalization-like experiences induced by psychedelics, suggesting that the sense of body ownership can be pharmacologically manipulated. Reports of drug-induced ego dissolution frequently include descriptions of a loss of ownership over one's body (e.g.,

“I felt disconnected from my physical being, my body”; “ looked down at my hand and didn't feel anything that would indicate that this was my hand I was looking at." An intriguing hypothesis is that top-down constraints on body representation are loosened in the psychedelic state. In the rubber hand illusion, for example, it has been hypothesized that the high-level prior probability that one's actual hand is truly one's own is decreased. There is preliminary evidence for a weakening of top-down perceptual priors in the psychedelic states, as evidenced by reduced binocular rivalry switching rate and occasional phenomenal fusion of rival images under psilocybin and ayahuasca, as well as reduced susceptibility to the “hollow mask” illusion (unpublished result of Torsten Passie's hollow mask study at the Hannover Medical School in Germany). In addition, a recent study showed that LSD attenuates top-down suppression of prediction error in response to surprising auditory stimuli, as measured by mismatch negativity in the auditory oddball paradigm. It is possible that a similar disruption of top-down processing of somatosensory stimuli plays a role in the modulation of body ownership by psychedelics.

Thus, assuming that there is a phenomenology of body ownership in ordinary experience, available evidence from open-ended interviews and self-report questionnaires tentatively suggests that it can go missing during certain conscious states induced by meditation and psychedelics—not only for specific body parts but also for the whole body. However, more evidence is needed to confirm this hypothesis, as well as a rigorous definition and measurement of the sense of body ownership.

Bodily awareness

Bodily awareness can be defined as the conscious awareness of bodily sensations in general, including tactile, proprioceptive and interoceptive stimuli. A number of authors have argued that bodily awareness constitutes a form of self-consciousness, in part because it grounds self-ascriptions that are immune to error through misidentification. When one feels pain, for example, one cannot be wrong about who is in pain; generally, bodily sensations are said to be immune to error through misidentification insofar as the only body that one can have access to through them is one's own. This kind of consideration has led some philosophers to argue that bodily awareness constitutes a basic form of self-consciousness through which an embodied subject is directly conscious of the bodily self. In recent years, a similar idea has emerged within neuroscience with a particular focus on interoception, the awareness of internal bodily sensations such as cardiac, respiratory and gastric signals. It has been argued that interoceptive awareness grounds a core sense of self in normal experience, anchoring oneself in one's body. It should be noted that this idea does not necessarily rest on the hypothesis that there is a specific phenomenology of body ownership, although it is not always easy to disentangle the claim that one's body is experienced as one's own from the claim that one's bodily sensations underlie a consciousness of oneself as a bodily subject. The distinction of these two claims turns on the clarification of their theoretical commitments. Here, we will leave this issue aside, and assume that bodily awareness constitutes a basic form of self-consciousness, whether or not it is associated with a specific phenomenology of ownership.

Can meditative practices and psychedelics induce a partial or complete loss of bodily awareness? Given the focus of many meditation practices on bodily sensations, either through open awareness of all present moment sensations (in open monitoring) or through focal awareness of the breath (in focused attention), one would not expect bodily awareness to fade away during meditation practice. The meta-analytic cluster of activation of the insular cortex during OM, FA, and LK reported in the previous section also suggests that bodily awareness is central to these meditation practices, given that the insula is an important hub for the processing of interoceptive signals. Nonetheless, there is preliminary evidence that bodily awareness can be reduced in certain forms of mindfulness meditation, at least for highly experienced practitioners. For example, subject S from Ataria and colleagues' study reported that in the “selfless” altered state of consciousness voluntarily achieved through meditation, bodily sensations were “almost invisible” and reduced to a subtle and indistinct background presence:

“there is a sense of something happening, it is very hard to tell if there is a sense of body, it is more in the background… a sense of body-ness, but it's so spread… I am not dead; there is a kind of very light sense of body in this experience." In their analysis of the same data, Dor-Ziderman and colleagues comment that

“even when the [sense of boundaries] disappears, a minimal level of dynamic proprioception continues to exist: there remains a sense that there is a body without any experience of [a sense of boundaries]."

It is debatable whether proprioceptive awareness was retained in this state, given the difficulty that subject S had in locating his bodily sensations on a body-part-centered spatial frame of reference (

“I can't tell you at all which [hand] is right and which is left. I don't know.)" Nonetheless, it is plausible that some degree of interoceptive awareness was preserved, which is consistent with the fact that the body was merely experienced as some kind of vague background presence. Berkovich-Ohana and colleagues also found that experienced mindfulness meditators could significantly inhibit awareness of bodily sensations during their practice:

“The experience of the body faded. There was a sense of body in the background, not in front of consciousness” (subject 4);

“A wide experience with un-defined boundaries. A sense… that I am dissolving, my body dissolving.” (subject 5);

“There was a vanishing of bodily sensations” (subject 11).

While it remains unclear whether bodily awareness can completely disappear during meditation, there is evidence that subjects can lack any awareness of their body and of specific bodily sensations in altered states induced by psychedelic substances. As previously mentioned, early studies with mescaline and LSD reported depersonalization-like effects which occasionally involved a loss of bodily awareness. In the psychometrically validated 5D-OAV questionnaire commonly used to assess the subjective experience of altered states of consciousness, healthy participants score rather high on the

“disembodiment” factor, which includes the item

“it seemed to me as if I did not have a body anymore,” after administration of psilocybin and LSD. The strength of the subjective effects of LSD (as measured by the mean score on the 5D-ASC questionnaire) was found to correlate with the magnitude of increase in functional connectivity in a somatomotor network including the primary motor and sensorimotor cortices, the caudal premotor cortex and the superior parietal lobule.

In a recent neuroimaging study of DMT, a drug whose short lasting subjective effects are more intense and immersive than those of psilocybin or LSD, almost all participants reported a loss of awareness of their body for several minutes during the peak of the experience in post-hoc microphenomenological interviews:

“I lost awareness of gravity and awareness of my body." There is also considerable anecdotal evidence from narrative reports that psychedelics can radically disrupt bodily awareness, an effect often associated with the dissolution of the sense of self:

“It felt as if ‘I' did no longer exist. There was purely my sensory perception of my environment, but sensory input was not translated into needs, feelings, or acting by 'me'. Also, I felt disconnected from my physical being, my body." Anecdotal evidence regarding the dramatic effects of 5-MeO-DMT suggests that this drug may be particularly effective at suppressing bodily awareness, although controlled studies of these effects are needed.

Thus, it seems that certain meditation practices may inhibit awareness of bodily sensations, reduced in some cases to a mere background interoceptive awareness, while psychedelic substances (DMT and 5-MeO-DMT in particular) may completely suppress awareness of the body. Sensory deprivation is likely to be a factor in this reduction of bodily awareness: meditators are usually sitting in silence with eyes closed, while participants of neuroimaging studies of psychedelics are often lying down in supine position with a blindfold. The lack of somatosensory and motor feedback in these states may play an important role in the loss of bodily awareness. Interestingly, two recent findings emphasize the influence of sensory deprivation on the plasticity of body representation: short-term visual deprivation has been shown to lead to significantly larger proprioceptive drift in the rubber hand illusion, while audio-visual sensory deprivation has been found to degrade the boundary of the whole body peripersonal space. These results suggest that sensory deprivation enhances the flexiblity of body representation, and could facilitate the disruption of bodily awareness in meditation and psychedelic states.

Finally, it is important to note that psychedelic drugs, just like some styles of meditation, may also increase awareness of the body, especially at lower doses associated with salient and unusual bodily sensations (see section Toward a multidimensional model of altered self-consciousness below). Finally, it can also be observed that drug-induced states are not the only known altered states of consciousness in which bodily awareness can fade away altogether; there is good evidence that this can also be the case in so-called “bodiless” dreams and “asomatic” out-of-body experiences.

Spatial self-location

A third notion associated with a minimal form of self-consciousness rooted in multisensory integration is spatial self-location. It has been argued that perceptual experience, and visual experience in particular, is self-locating. This idea typically combines two claims: first, in virtue of being structured by an egocentric frame of reference

6, visual experience represents the location of the point of origin of this reference frame relatively to environmental landmarks; secondly, the location of this point of origin is represented as the location of the subject (i.e., where I am located with respect to objects in the visual scene). This analysis may be extended to other sensory modalities whose content presumably has a perspectival structure centered onto a single point of origin, such as auditory perception.

Whether perspectival structure always entails self-locating content—namely a representation of the location of the origin as the location of the subject—is a matter of debate. Some authors have argued that self-locating content also requires the ability to act upon objects perceived in one's environment. Nonetheless, it is generally agreed that ordinary perceptual experience has self-locating content. In other words, one normally experiences oneself as located at a certain distance with respect to objects perceived in one's environment. Interestingly, both questionnaire data and behavioral measurements suggest that self-location can be manipulated in full-body illusions, such that subjects may feel located outside of their own body or closer to the virtual avatar over which they feel ownership during the illusion. Similarly, out-of-body experiences and heautoscopic phenomena of clinical origin, in which subjects hallucinate seeing their own body from the outside, appear to involve a shift of self-location (often to an elevated position) associated with a hallucinatory visuospatial perspective.

Such experimental and clinical evidence isolating spatial self-location as a dissociable component of ordinary experience has led researchers to claim that it constitutes an important aspect of bodily self-consciousness , and even a minimally sufficient condition for self-consciousness. Interestingly, there is evidence that both meditation and psychedelics may radically disrupt the experience of being located somewhere in space; moreover, this disruption appears to be often associated with reports of “selflessness” or “ego dissolution,” suggesting that spatial self-location is indeed a basic and important building block of self-consciousness. The highly experienced mindfulness meditator studied by Ataria and colleagues described the selfless state he reportedly achieved for the experiment in the following terms:

“it's like falling into empty space… and a sense of dissolving… and there really isn't a center… I don't have any kind of sense of location… I have no idea where I am in stage three, it's all background, I'm not there basically, just world, so there's no real location at all in stage three. It's very minimal, almost nothing… When there's no boundary, there's no personal point of view, it's the world point of view, it's like the world looking, not [me] looking, the world is looking.” As Dor-Ziderman and colleagues comment, in this meditation-induced altered state of consciousness, it seems that

“the sense of orientation in space is lost altogether." In another neuroimaging study of long-term mindfulness meditation practitioners, Berkovich-Ohana and colleagues found that some of them were able to induce what they described as a state of “spacelessness,” reported in the following terms:

“the center of space became endless, without a reference point in the middle” (subject 4);

“it was a sense of spaciousness, boundlessness… there was no clarity where the center is and where is the periphery. There was no quality of border” (subject 11)

Likewise, there is converging evidence from subjective reports that psychedelic drugs can induce a loss of spatial self-location, associated to loss of boundary between self and world and a feeling of unity with everything:

“I felt myself mold into the world around me…,” “My mind started to blend with everything” (R.M., unpublished data from online survey). On the psychometrically-validated 5D-ASC questionnaire, subjects score high on the factor related to “experience of unity” after administration of LSD and to a slightly lesser extent psilocybin. This factor includes the items

“it seemed to me that my environment and I were one” and

“everything seemed to unify into oneness.” Moreover, studies using custom questionnaire items have also measured high scores for

“I experienced a sense of merging with my surroundings” after administration of psilocybin and LSD. A recent online survey on the effects of 5-MeO-DMT with 515 participants also found that the overwhelming majority of respondents scored positively on items of the Mystical Experience Questionnaire corresponding to

“Loss of your usual sense of space” (95% of respondents),

“Loss of usual awareness of where you were” (88% of respondents) and

“Being in a realm with no space boundaries” (87% of respondents).

In addition to questionnaire data from controlled studies, there is a large amount of anecdotal evidence from online narrative reports that DMT and 5-MeO-DMT can induce a loss of self-location:

“at the time I didn't know where it was, or where I was…I didn't know what had happened before this point, in-between, sideways, up, down or anywhere” (DMT, report from

www.dmt-nexus.me),

“I was the universe, I was everywhere and nowhere, everything and nothing all at the same time” (5-MeO-DMT, report #49690 from Erowid.org),

“The feeling was very cosmic, of oneness with everything” (5-MeO-DMT, report #78485 from Erowid.org),

“an immediate complete dissolution of any identity and a merging into the Oneness, timeless, pure awareness and light energy of the Universe… Similar in some ways with a previous Samadhi meditation experience” (5-MeO-DMT, report #5804 from Erowid.org; see below on

Samadhi meditation). A similar phenomenological report can be found in a (non-academic) monograph on 5-MeO-DMT:

“I was completely disconnected somatically, unable to locate or feel my body… unable to locate myself—or anything else—anywhere in particular. I had no body, not even the slightest semblance of a dream-body or mental-body, and I had absolutely no sense of where I was” (

Masters, 2005). Taken at face value, these reports suggest that psychedelic drugs can induce experiences which may have perceptual content without spatial—or at least self-locating—content. Although narrative reports from online databases offer at best anecdotal evidence, their convergence with questionnaire data from multiple controlled studies suggests that they may be taken into consideration to inform hypotheses about the effect of psychedelics on the sense of self-location.

We note that these reports of meditative and psychedelic experiences lacking spatial self-locating content might be reminiscent of reports of conscious episodes during dreamless sleep, which allegedly lack any form of self-consciousness and spatial content. Jennifer Windt has argued that such dreamless sleep experiences might be characterized by “pure subjective temporality,” conceived as the minimal phenomenology of temporal self-location (“nowness”) and duration. If such states do exist, we can plausibly hypothesize that they might also be induced by meditation and psychedelic drugs, on the basis of the preliminary evidence discussed in this section. However, we also note that many reports of drug-induced ego dissolution, especially with 5-MeO-DMT, insist on the timeless character of the experience, described as a complete loss of the sense of temporal duration. The aforementioned online survey on the effects of 5-MeO-DMT found that the overwhelming majority of respondents scored positively on items of the Mystical Experience Questionnaire corresponding to “Loss of your usual sense of time” (97% of respondents),

“Experience of timelessness” (90% of respondents),

“Sense of being outside of time, beyond past and future” (89% of respondents) and

“Feeling that you experienced eternity or infinity” (88% of respondents). Interestingly, some mindfulness meditators have been reported to achieve a similar disruption of the phenomenology of duration through their practice. Thus, we tentatively suggest that some drug-induced and meditative states might lack both spatial and temporal self-locating content.

From a neurophysiological point of view, it is interesting to note that the intensity of drug-induced ego dissolution reported by participants under LSD was found to correlate with the magnitude of increased functional connectivity in the bilateral insular cortex and the temporoparietal junction. Meanwhile, Dor-Ziderman and colleagues found that the transition from minimal self-consciousness to a “selfless” state characterized by a loss of body ownership and self-location in experienced meditators was correlated with a decrease in beta power in the temporoparietal junction. These findings are intriguing since there is evidence from neuroimaging studies of out-of-body experiences and full-body illusions that the temporoparietal junction plays a role in processing spatial self-location. Given that a number of intracranial EEG and MEG studies have suggested that beta oscillations encode top-down modulations of predictions, it is intriguing to speculate that decreased beta power in the TPJ may relate to weakened top-down constraint on multisensory processing underlying self-location. In addition, the insular cortex is associated with the integration of interoceptive information, and may play an important role in body awareness and ownership. Thus, while the modulation of beta oscillatory power and functional connectivity in the temporoparietal junction in some psychedelic and meditative states may be linked to the disruption of spatial self-location, the modulation of functional connectivity in the insula during drug-induced ego dissolution might be specifically related to the loss of bodily awareness. However, more data is needed to confirm these hypotheses.

To conclude this section, it should be noted that our overview of narrative and multisensory aspects of self-consciousness has left out the notion of the sense of agency, typically defined as the experience of being in control of one's actions. There are three reasons for this omission aside from spatial constraints. Firstly, the sense of agency is an ambiguous concept, which has been construed both as a feeling of control over one's bodily movements allegedly produced by comparator mechanisms, and as a feeling of control over the production of one's thoughts. Secondly, there is little available evidence regarding how the sense of agency, in either construal, may be modulated by meditation and drug-induced states. Although experiences of self-loss with both psychedelics and meditation typically occur when subjects are immobile (in seated or supine position), increased voluntary control over one's breathing in certain styles of meditation could modulate the sense of bodily agency. Further evidence could be provided by measures of intentional binding during meditation and psychedelic states. Likewise, one could expect attentional control of spontaneous thoughts in meditation to have an effect on the sense of cognitive agency, if this notion is valid. Finally, it is worth mentioning that the claim that voluntary movements and thoughts are ordinarily accompanied by a pervasive sense of agency has recently come under criticism. According to a more deflationary account, there is no special phenomenology of agency in ordinary experience.

Continued below.

realitysandwich.com

realitysandwich.com