mr peabody

Bluelight Crew

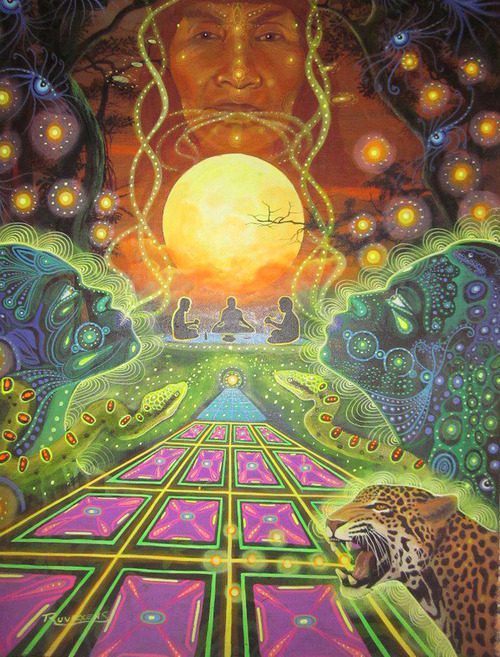

San Pedro Ceremonies in Peruvian Shamanism

by Katie Stone | Psychable | 29 Mar 2022

In the Andean mountain range of Peru, the use of San Pedro cactus goes back nearly 8,000 years. Archeological evidence suggests that ceremonies using San Pedro tea were held at a massive temple site called Chavin de Huantar. Even today, descendants of these cultures continue to practice ceremony and ritual in what is broadly known as “shamanism.” San Pedro cactus comprises just one aspect of Peruvian Shamanism, existing both as part of a cultural tradition and healing modality.

A traditional healer, sometimes called a yachakkuna, facilitates the San Pedro ceremony, creating a ceremonial altar known as a Mesa that serves as a primary healing tool. Before we get into more specifics about the Mesa, let’s review the history and cosmology that underlies the San Pedro ceremony. There is no room to offer a comprehensive overview of Peruvian Shamanism, but this article will get you started and direct you toward more resources.

The History of San Pedro Ceremony

Long before the Spanish missionaries and conquistadors arrived, the indigenous cultures of modern-day Peru utilized psychoactive plants ceremonially for spiritual and medicinal purposes. Evidence of use has been found in caves, where fossilized cactus remains were dated back to 6800-6200 BCE. Interestingly, more recent samples were present as well, suggesting that these caves in the Callejon de Huaylas valley were visited for similar purposes throughout history.

Near the end of the millennia, evidence of San Pedro use in ceremony was found in ceramics and textiles. Archeologists suggest that around 200 BCE and 600 CE, the San Pedro cactus was cultivated, becoming the first domesticated psychedelic plant that we currently know of. Once the Spanish arrived in the 15th century, traditional San Pedro ceremonies were seen as a sign of devil-worship; the Spanish invaders persecuted the indigenous populations for practicing folk healing or spirituality.

During the colonial period, the indigenous peoples maintained some of the traditions by blending the original name huachuma with Christian mythology, referring to the cactus as “San Pedro” in reference to St. Peter, who is said to guard the gates of heaven.

Cosmology of Peruvian Shamanism

In Peruvian Shamanism, like in many indigenous traditions, the world is believed to exist in three realms: the Upper, Middle, and Lower. In the Quechua language, these translate to Hanaq Pacha (upper), Kay Pacha (middle), and Ukhu Pacha (lower). “Pacha” refers to ground or soil, but not only in the literal sense but also the metaphysical sense.

The Ukhu Pacha can resemble Western ideas of the subconscious and shadow archetypes, the places where awareness must enter so that transformation can occur. Kay Pacha speaks to the experiences of being in this worldly existence. It is the reality we are born into, the multi-sensorial experience of the collective, which includes seen and unseen forces, energies, and spirits. Hanaq Pacha is the highest realm of consciousness, the place of infinite wisdom and divine power — and “celestial denizens” or beings. San Pedro can be used to ascend to this realm to return with power, insight, and wisdom as well.

Symbolically, these three realms are represented in the Chakana, or Andean Cross, a tiered, square-shaped symbol that is used to outline the ceremonial altar, called the Mesa, used in the San Pedro ceremony. According to researcher Matthew Magee, “the Mesa Tradition affirms the existence of humanity’s ability to access these three dimensions, inner, outer, and transcendent… the Mesa itself is an embodiment of this multidimensional gateway or portal” to other realms, not only of consciousness but of reality.

The Mesa used in San Pedro Ceremony

If you are familiar with Spanish, you know that mesa translates to ‘table’ in English. But mesa is derived from the Latin mensa, which means ‘altar table.’ Rather than thinking of a Mesa as a table altar, think of it as an altar spread out on the gound with several icons, symbols, and artifacts that serve as the physical connection point between realms to open up communication with ancestors.

According to scholars Donald Joralemon and Douglas Sharon, the use of the Mesa in ceremony is thought to go back to 2000 BCE. This shamanic technology is rooted in the practice of animism, which is evident in all indigenous cultures as a way of life. Within the ceremony, the “shaman,” or yachakkuna, navigates the three realms through the Mesa portal and later returns to this terrestrial plane with knowledge or power that would otherwise be inaccessible. Knowledge accessed might be used to heal, but it might just be information. In this way, it is not only the San Pedro cactus but also the Mesa that serves as a vehicle or tool, acting as its own form of indigenous healing knowledge.

In Peruvian Shamanism, ancestors are not limited to humans but can also include animals, trees, and even mountains. The items that are arranged on the Mesa not only represent these ancestors but in the way that the Catholic Eucharist becomes the body of Christ, the Mesa elements transform into whatever it is they represent. In this way, the participant can communicate directly with these forces and energies during the San Pedro ceremony through the Mesa.

5 Objects for the San Pedro Ceremony altar

Objects included in a Mesa vary but contain stones, artifacts from sacred places, textiles, and personal items of relevance. The Mesa tradition varies by region, with some focusing on personal altars to facilitate healing.

Each element in the Mesa is placed with deep respect and intention, imbued with social and personal meaning. However, five components seem always to be present and placed in accordance with the directions: a stone (south), a seashell (west), a feather (north), a white candle (east), and one’s most sacred, personal object (center). The items are placed with the Mesa following both celestial alignment and alignment to the holy city of Cusco.

With these five elements, Peruvian Shamanism calls in five directions for the ceremony rather than the four cardinal directions. These objects hold many layers of symbol and meaning, not only in terms of cosmology but also in alchemy, physics, and molecular transformations. For more insight, check out “Peruvian Shamanism: The Pachakuti Mesa,” written by Matthew Magee.

San Pedro Ceremony and the Mesa

All ceremonies can be said to have a beginning, middle, and end at their most basic level. A ceremony is shaped by smaller rituals that offer structure to help the ceremony unfold. There is always an element of spontaneity that can emerge in any psychedelic ceremony. Ritual helps to steer and direct energies toward the desired flow, offering a structure that allows participants to navigate both their internal consciousness and the expanded realms accessed through the Mesa.

Keep in mind that authentic San Pedro ceremonies held with traditional shamans in Peru will be very different from those held by neo-shamanic practitioners or at home among friends or family. San Pedro is just one of several types of plant medicines that might be used. While a yachakkuna would take the time to build a traditional Mesa, prepare additional plant medicines, and work through several rituals before ingesting San Pedro, practitioners who facilitate San Pedro ceremonies outside of the traditional lineage are unlikely to embrace the same cosmology and healing technologies developed over thousands of years of use.

Last edited: