The Nitrous Oxide Philosopher

by

Dmitri Tymoczko | The Atlantic

Do drugs make religious experience possible? They did for James and for other philosopher-mystics of his day. James' experiments with psychoactive drugs raise difficult questions about belief and its conditions

He has short hair and a long brown beard. He is wearing a three-piece suit. One imagines him slumped over his desk, giggling helplessly. Pushed to one side is an apparatus out of a junior-high science experiment: a beaker containing some ammonium nitrate, a few inches of tubing, a cloth bag. Under one hand is a piece of paper, on which he has written,

"That sounds like nonsense but it is pure on sense!" He giggles a little more. The writing trails away. He holds his forehead in both hands. He is stoned. He is William James, the American psychologist and philosopher. And for the first time he feels that he is understanding religious mysticism.

The psychedelia of the 1960s was foreshadowed by events in the waning years of the nineteenth century. This first American psychedelic movement began with

an anonymous article published in 1874 in The Atlantic Monthly. The article, which was in fact written by James, reviewed

The Anaesthetic Revelation and the Gist of Philosophy, a pamphlet arguing that the secrets of religion and philosophy were to be found in the rush of nitrous oxide intoxication. Inspired by this thought, James experimented with the drug, experiencing extraordinary revelations that he immediately committed to paper.

What's mistake but a kind of take?

What's nausea but a kind of -ausea?

Sober, drunk, -unk , astonishment. . . .

Agreement--disagreement!!

Emotion--motion!!! . . .

Reconciliation of opposites; sober, drunk, all the same!

Good and evil reconciled in a laugh!

It escapes, it escapes!

But--

What escapes, WHAT escapes?

This experience, which in James' words involved "the strongest emotion" he had ever had, remained with him throughout his life.

In 1882 he first described his experiments with the drug; in 1898 he published an article titled "Consciousness Under Nitrous Oxide" in the

Psychological Review; in 1902 he recounted the experience in his greatest work,

The Varieties of Religious Experience ; and in 1910, in the last essay he completed, he implied that nitrous oxide had had an abiding influence on his thinking.

When the drug wore off, James found that his mystical insights had disappeared. What remained were incomprehensible words--"tattered fragments" that seemed like "meaningless drivel." Being a philosophical visionary rather than a garden-variety recreational drug user, however, James was not inclined to let his sober consciousness have the final say. On the contrary, he took his experiences with nitrous oxide as evidence that human life was more richly varied than he had previously (and soberly) imagined.

"Some years ago," he wrote in

Varieties,

I myself made some observations on . . . nitrous oxide intoxication, and reported them in print. One conclusion was forced upon my mind at that time, and my impression of its truth has ever since remained unshaken. It is that our normal waking consciousness, rational consciousness as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different.

For James, these alternate forms of consciousness were accessible only by way of artificial intoxicants. Others, he hypothesized, were able to reach them without the aid of drugs: in his view the great religious mystics, and certain mystical philosophers including Hegel, were "unusually susceptible" to these extraordinary forms of consciousness.

James' experiences with nitrous oxide helped to crystallize some of the major tenets of his philosophy. His writings emphasize, for instance, the notion of pluralism, according to which "to the very last, there are various 'points of view' which the philosopher must distinguish in discussing the world." Nitrous oxide had revealed in the most dramatic way possible the existence of alternate points of view. Which was the "real" William James--the drug-addled visionary who spouted meaningless mystical drivel, or the sober, unmystical psychologist whose researches brought him international fame? James' philosophy was based on the thought that the good life--for society and, by extension, for an individual as well--involves a plurality of perspectives, of which the mystical and the scientific are only two. Equally important to the mature Jamesian outlook was the thought that religious experiences are psychologically real--powerful and palpable events that can have important long-term consequences whether the beliefs to which they give rise are true or not. Drugs helped James to understand what religious belief was like from the inside. When he took nitrous oxide, he was for all intents and purposes a religious mystic. ("Thought deeper than speech!" he wrote while on the drug. "Oh my God, oh God, oh God!") Nitrous oxide was the passport that allowed James to see religion from the believer's perspective, traveling between the worlds of science and faith.

Yet James' experiments with nitrous oxide, when they have been noticed at all, have been variously derided. Even in the nineteenth century, skeptical scientists found his interest in exotic mental phenomena misguided, if not reckless. Religious believers tend to resent the comparison of intoxication to religious inspiration. Veterans of the counterculture, who have all had similar if not more-intense drug revelations, tend to think of James as a dabbler. These criticisms are shortsighted, and slight the fact that James was America's first philosophical genius. Perhaps more than any philosopher before him, he succeeded in combining the skepticism of the empirical scientist, the form of consciousness that "diminishes, discriminates, and says no," with the hyperbole of the mystical visionary, the form of consciousness that "expands, unites, and says yes." If drugs helped him to open the doors of consciousness in this welcoming way, perhaps we should rethink some of our assumptions about drug use and its possible role in human life. For example, can drugs play a role in authentic religious experience? And if so, what should be the legal and moral status of religious drug use?

These questions lead into a fascinating tangle of history and philosophy, much of which has surprising relevance to contemporary policy. Indeed, for more than thirty years courts, legislatures, and philosophers have been debating James' questions, reaching a bewildering variety of incompatible conclusions. Some courts have held that religious drug use is legitimate and even deserves constitutional protection; others--including the Supreme Court--have rejected these arguments. In 1993 Congress passed a law allowing for the sacramental use of peyote, a powerful hallucinogen; yet politicians continue to excoriate "drug use," as if "drugs" were a single sort of unequivocally bad thing. (One wonders how many of the congressional representatives who passed the peyote law would be willing to acknowledge publicly their support for hallucinogenic drug use.) William James thought more clearly about these issues than we are able to think today, and we may want to look to James as we consider the place of drugs in contemporary life.

An "Adamic" Revelation

James' interest in nitrous oxide was prompted by a man named Benjamin Paul Blood. Born in 1832, Blood --a farmer, philosopher, athletic strongman, prodigious calculator, debunker, inventor, mystic, and forgotten visionary, and the author of the pamphlet

The Anaesthetic Revelation and the Gist of Philosophy --is a classic figure of nineteenth-century America. By his own confession an idler, a "fraud," haphazardly educated and with little gift for sustained argument, Blood spent his eighty-six years in Amsterdam, a town in upstate New York. But despite his limitations, or perhaps because of them, he devoted his life to philosophy. The bulk of his writing consists of letters to the editors of local papers: the Amsterdam

Gazette and

Recorder , the

Utica Herald , the

Albany Times . (Some of these letters were amalgamated for the

Journal of Speculative Philosophy.) He published a few poems in

Scribner's Magazine . Eventually he wrote a book,

Pluriverse: An Essay in the Philosophy of Pluralism.

Blood could multiply large numbers in his head. He could demolish the itinerant lecturers who were a staple of nineteenth-century American popular culture. On one occasion he demonstrated to an astonished crowd how a visiting spiritualist had produced apparently ghostly occurrences. On another he used the doctrines of what was then called modern philosophy to challenge an astronomer's glorification of space: Why, he asked, should we be impressed by the size of the solar system if size is relative to the perceiver? Would not a giant find the universe small? And is it not, therefore,

we who make space large, since without us it would be neither large nor small? Amsterdam was not always up to these speculations, but it loved Blood nonetheless. Bewildered newspaper editors cheerfully printed his grandiose contributions. Townspeople spoke in admiring terms of Blood's letters from such luminaries as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Grover Cleveland, and William James. And, as Blood was not above mentioning, in a poll conducted by one of the local papers he placed as "one of the twelve leading citizens" of the town--number six, to be precise.

The outside world, however, was less kind. The portentous letters Blood directed to innumerable nineteenth-century eminentos were for the most part met with polite dismissal. One appeal, it is true, produced an invitation to visit Alfred Lord Tennyson; another resulted in a lengthy and affectionate correspondence with James. But in the main Blood lived his long life alone. Thumbing through the detritus of his "papers," the inconsequential letters and crumbling newspaper clippings that some admirer deposited in Harvard's Houghton Library, one catches the unmistakable whiff of intellectual tragedy. Blood was the very picture of the half-baked American eccentric, a snake-oil salesman with philosophical pretensions. Born in the wrong place and at the wrong time, he knew too little to put his talents to good use, and too much to let them atrophy gracefully.

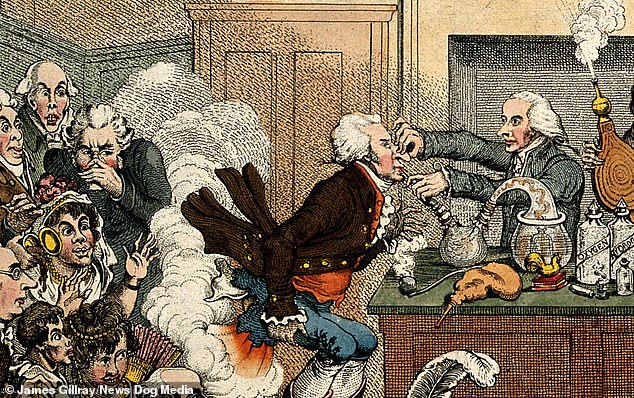

Blood's obsession with

nitrous oxide began at a dentist's office. Nitrous oxide, or "laughing gas," had been discovered in 1772 by Joseph Priestley. Its distinctive psychoactive properties were noticed twenty-seven years later by Sir Humphrey Davy, whose

Researches, Chemical and Philosophical, Chiefly Concerning Nitrous Oxide, or Dephlogisticated Nitrous Air, and Its Respiration records a series of attempts to try to find a use for the new drug. Notwithstanding Davy's efforts,

the drug was used in the early half of the century primarily for recreation. One nineteenth-century observer wrote that ether, which has similar psychoactive properties, had

"long been the toy of professors and students," and noted that

"the students at Harvard used to inhale sulphuric ether from their handkerchiefs, and that it intoxicated them, making them reel and stagger." Ether was first put to its modern use in 1846, when, in one of the major triumphs of nineteenth-century medicine, W.T.G. Morton, an American dentist,

"administered the vapor of sulphuric ether to a patient, and extracted a tooth, the patient being in a state of entire insensibility." A similar result followed shortly thereafter with nitrous oxide, and the modern practice of anesthesia was born.

Enter Blood. In the preface to his book,

Pluriverse, he wrote,

It was in the year 1860 that there came to me, through the necessary [medical] use of anaesthetics, a Revelation or insight of the immemorial Mystery which among enlightened peoples still persists as the philosophical secret or problem of the world. . . . After fourteen years of this experience at varying intervals, I published in 1874 "The Anaesthetic Revelation and the Gist of Philosophy," not assuming to define therein the purport of the illumination, but rather to signalize the experience, and in a résumé of philosophy to show wherein that had come short of it.

Blood held that the great metaphysical philosophers, from Plato to Hegel, had all experienced something like what he had experienced while on nitrous oxide. This "anaesthetic revelation," he argued, was "primordial," "Adamic," and incommunicable. He wrote to James,

"Philosophy is past. It was the long endeavor to logicize what we can only realize practically or in immediate experience."

Tireless proselytizing on behalf of his pamphlet--Blood sent copies to virtually everyone he could think of--eventually resulted in the formation of a tiny group of nitrous oxide philosophers, who agreed that the drug produced some sort of incommunicable metaphysical illumination. One was Xenos Clark, a philosopher who died young in Amherst, Massachusetts. (His last days were spent collecting his writings on the "anaesthetic revelation," which he asked James to transmit to posterity.) Other experimenters included some impressive figures: Edmund Gurney, an English spiritualist who had written a heavy two-volume catalogue of telepathic events, hauntings, and other ghostly occurrences (

Phantasms of the Living, 1886); J. A. Symonds, the poet, historian, and biographer; Professor William Ramsay, a 1904 Nobel laureate and the discoverer of the inert gases; and, of course, William James. All reported "metaphysical insights" under the influence of nitrous oxide or similar drugs. Even Tennyson, while he was recovering from an experience with ether, blurted out "a long metaphysical term"--unfortunately not recorded.

Many of these figures were associated with the British Society for Psychical Research. Founded in 1882, the society (which still exists) aimed to test with an unbiased, scientific eye reports of a wide variety of unusual experiences not recognized by the academic establishment. Its province was what we would now call parapsychology: claims of hauntings, telepathy, spontaneous mental healings, visions of the dead, and other supernatural occurrences. Members conducted research, collected reports of paranormal activity, and published a journal. Blood's claim--that nitrous oxide reliably produced the experience of metaphysical illumination--engaged the society, and its members immediately set about to verify or disprove it.

James was attracted to the society by its peculiar mixture of scientific caution and romantic optimism. The son of a

Swedenborgian, James was permanently suspended between the poles of faith and reason. Although he was uncomfortable with his father's visionary excess, he was scandalized by the neglect of this very quality on the part of the more reputable sciences. He wrote in

"What Psychical Research Has Accomplished,"

No part of the unclassified residuum [of human experience] has usually been treated with a more contemptuous scientific disregard than the mass of phenomena generally called mystical. Physiology will have nothing to do with them. Orthodox psychology turns its back on them. Medicine sweeps them out; or, at most, when in an anecdotal vein, records a few of them as "effects of the imagination"--a phrase of mere dismissal, whose meaning, in this connection, it is impossible to make precise. All the while, however, the phenomena are there, lying broadcast over the surface of history.

James even went so far as to compare this disregard to that of a religious believer who refuses to acknowledge scientific considerations that weigh against his or her cause: "Certain of our positivists keep chiming to us that, amid the wreck of every other god and idol, one divinity still stands upright,--that his name is Scientific Truth, and that he has but one commandment, but that one supreme, saying, Thou shalt not be a theist." James wanted a more radical empiricism, a science freed of preconceptions, for which the issue of religious belief had not been foreclosed ahead of the evidence.

It was Blood, more than any other single figure, who embodied this attitude. James' final published essay, "A Pluralist Mystic," was a sustained encomium of Amsterdam's finest philosopher. Blood's work, he wrote, "fascinated me so 'weirdly' that I am conscious of its having been one of the stepping-stones of my thinking ever since." Blood gave James confidence that empirical and mystical sympathies could be combined. James wrote,

One cannot criticize the vision of a mystic--one can but pass it by, or else accept it as having some amount of evidential weight. I felt unable to do either with a good conscience until I met with Mr. Blood. . . . I confess that the existence of this novel brand of mysticism has made my cowering mood depart.

Blood's was a "pluralist mysticism" because it presented his extraordinary mystical experiences simply as experiences, without chaining them to a grand systematic doctrine such as Christianity or Hegelian philosophy. Moreover, it provided others with a key to those experiences, nitrous oxide, with which they could test Blood's claims in controlled and scientific surroundings. It was, in short, a mysticism without dogma or conclusions--just the thing for a Harvard professor with strong religious sympathies.

Did religion begin with drugs?

DRUGS have long been associated with religion. Psychedelic mushrooms were used in Siberia more than 6,000 years ago. The ceremonial use of marijuana among the Scythians dates back almost 2,500 years. Haoma, a sacred drink of the Zoroastrians, and soma, an early Hindu analogue, are both presumed to have been made from psychedelic plants; scriptural references to the drinking of "sacred urine" have led some historians to propose that the plants in question may have included the Amanita muscaria mushroom, whose active ingredient passes into urine without a significant loss of potency. The ancient Greek cult of Dionysus used wine to provoke visions, and other Greek mystery cults may have used psychoactive substances. (The use of wine in Christian rituals may be a remnant of similar practices.) In the New World the religious use of psychedelic mushrooms has been widely practiced--among the Mayans, in the Aztec empire, and today, by many members of the Native American Church. In view of this extensive transcultural association between religion and drug use, at least one scholar--R. Gordon Wasson, an authority on mushroom cults--has proposed that the religious impulse itself originated with drugs, as a confused reaction to intense experiences provoked by the accidental ingestion of psychoactive plants.

James' interest in the connection between drugs and religion was unusual in one crucial respect. Unlike other drug-using mystics, he did not see drugs as a means to understanding higher religious truths; on the contrary, he used drugs because they provided him with access to beliefs that were potentially false. At the time of his experiments with nitrous oxide James thought that religion, though it might be based on untruth from the scientific point of view, was nevertheless good for one. It had survival value: in the long run religion helped human beings to live rich and happy lives. In "Is Life Worth Living?" he offered the analogy of a mountain climber who is stuck in a tight place.

Suppose, for instance, that you are climbing a mountain, and have worked yourself into a position from which the only escape is by a terrible leap. Have faith that you can successfully make it, and your feet are nerved to its accomplishment. But mistrust yourself, and think of all the sweet things you have heard the scientists say of maybes, and you will hesitate so long that, at last, all unstrung and trembling, and launching yourself in a moment of despair, you roll in the abyss.

This analogy, which emphasizes belief's potential usefulness rather than its truth, is utterly characteristic of James, a man who arrived at philosophy by way of medicine and psychology rather than physical science and logic.

At the age of twenty-eight James had fallen into a period of deep depression. Unable to see his way around the determinism of his materialist friends, he felt pessimistic, not just about the possibility of human freedom in a world of physical laws but also about his own aptitude for philosophy. The death of a favorite cousin, coupled with repeated bouts of physical illness, exacerbated his situation. Finally came a crisis. One night, walking into a darkened room, James had a sudden hallucinatory vision: a young man he had once seen, a patient at a mental hospital, black-haired, with "greenish" skin, sitting on a bench against the wall, his legs pressed up against his chest, moving only his eyes. "That shape am I," James wrote: a powerless waif, observing a world he could not change. After this, he said, "the universe changed entirely." He began to wake up each morning with dread in his stomach. For months he was afraid to go into the dark alone. Concealing his condition from the people around him, James quietly contemplated suicide.

Over the next few months his melancholia faded somewhat. Then, on April 30, 1870, a dam burst.

I think yesterday was a crisis in my life. I finished the first part of Renouvier's 2nd Essay and saw no reason why his definition of free will--"the sustaining of a thought because I choose to when I might have other thoughts"--need be the definition of an illusion. At any rate I will assume for the present--until next year--that it is no illusion. My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will. For the remainder of the year, I will abstain from the mere speculation & contemplative [meditation] in which my nature takes most delight, and voluntarily cultivate the feeling of moral freedom, by reading books favorable to it, as well as by acting.

James chose to believe in free will not because he thought it was true but because it was necessary to his well-being. Like the mountain climber facing a life-or-death jump, he simply screwed up his courage and told himself that he was free. "In such a case," James wrote about the mountain climber, "(and it belongs to an enormous class) the part of wisdom as well as of courage is to believe what is in the line of your needs, for only by such belief is the need fulfilled."

James' career involved a progressive generalization of this thought. What began as a simple, almost physical necessity--a personal need to believe in free will in order to escape crushing moral paralysis--blossomed into a full-fledged philosophical doctrine. Beliefs, James eventually decided, were adaptations, like the giraffe's long neck or the tiger's claws: they were justifiable only insofar as they helped people to get around in the world. To believe what one needed to believe was no mere sign of weakness, as some of James' contemporaries contended. Rather, it showed a healthy understanding of what the process of believing was all about. In particular James argued that we are not obligated to be determinists, atheists, or materialists just because science might say that those are the correct and true doctrines. Ultimately science itself should be evaluated in terms of a higher moral question: To what extent are scientific beliefs conducive to human happiness?

Positive Illusions

SOME remarkable work by psychologists has recently illuminated James' position. Lyn Abramson, of the University of Wisconsin, and Lauren Alloy, of Temple University, have uncovered a number of "cognitive illusions" to which normal, healthy people are subject. Emotional health, they suggest, involves mildly overoptimistic presumptions and a corresponding insensitivity to failure, which result in a propensity to make straightforwardly false judgments. Perversely, the clinically depressed are often free of these cognitive illusions--they are, to use the subtitle of one of Abramson and Alloy's best-known papers, "Sadder But Wiser." Likewise, Shelley Taylor, a social psychologist, has studied the use of illusions by victims of trauma and illness. She found that like James' mountaineer, those who are unjustifiably optimistic tend to live better-adjusted and happier lives than people faced with similar situations who are thoroughly realistic about their prospects. (Taylor's book, Positive Illusions, provides an introduction to the subject of useful falsehoods.) Finally, Daniel Goleman, the author of Vital Lies, Simple Truths, and other neo-Freudians have argued that repression, the forgetting of unpleasant facts, plays a crucial role in emotional health. Overall, the psychological consensus seems to be that there can be a reasonably widespread conflict between truth and happiness. The best beliefs, as James clearly intuited, are by no means the truest ones. (Toward the end of his life James came to use "true" almost as a synonym for "useful," but the early James had not yet taken this radical step.)

James' life was filled with eloquent demonstrations, both large and small, of this principle. Testifying before the Massachusetts legislature, in 1898, he opposed a bill that would have prohibited Christian Scientists from practicing their "mind-cures." "You are not to ask yourselves whether these mind-curers really achieve the successes that are claimed," he told the lawmakers. "It is enough for you as legislators to ascertain that a large number of our citizens . . . are persuaded that a valuable new department of medical experience is by them opening up." On a more mundane level James supported the philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, his friend and mentor, with money that was from his own pocket but that James claimed had been collected from Peirce's many "anonymous admirers." This was an ordinary white lie, but in the context of James' lifelong concern for the practical consequences of belief it resonates with unusual grandeur. James' genius can be described as an unwillingness to overlook the numerous instances of benign deception (and self-deception) that mark human life. With inspired audacity he suggested a link between these banal little deceptions and the grand, useful, and possibly false world views that characterize religious belief.

James' interest in drugs needs to be seen in this light. Although as a philosopher James preached the "will to believe," as a man he was not always able to put this idea into practice. Without nitrous oxide he was a cautious scientist whose skeptical nature prevented him from experiencing the religious joys that his philosophy celebrated. "My own constitution," he said, speaking of mystical experiences, "shuts me out from their enjoyment almost entirely." With the drug he became an inspired visionary whose rantings would surely turn a Beat poet green with envy.

No verbiage can give it, because the verbiage is other.

coherent, coherent--same.

And it fades! And it's infinite! AND it's infinite! . . .

Don't you see the difference, don't you see the identity?

Constantly opposites united!

The same me telling you to write and not to write!

Extreme--extreme, extreme! . . .

Something, and other than that thing!

Intoxication, and otherness than intoxication.

Every attempt at betterment,--every attempt at otherment,

--is a--

It fades forever and forever as we move.

Drugs, in short, gave James the theorist who dared people to believe what accorded with their needs the ability to do just that.

The Freedom to Believe

AMERICANS, it is often remarked, are confused about drugs. The image of William Bennett giving up his cigarettes in order to lead the nation's War on Drugs exemplifies this confusion. We tolerate cigarettes and alcohol but prohibit the recreational use of similarly mild intoxicants, including marijuana. We pour billions of dollars into law enforcement but devote only a tiny fraction of this amount to the medical treatment and rehabilitation of drug addicts. Courts impose widely disparate punishments for the possession and use of chemically similar substances, notably crack and powdered cocaine. But perhaps the most egregious area of inconsistency involves religious drug use. Faced with the claim that drug use contributes importantly to religious belief, courts have made a number of confused and conflicting judgments.

In 1964 the California Supreme Court held that members of the Native American Church, an association of Native American groups all of whom use peyote in their religious rituals, had a First Amendment right to use the drug. In subsequent years

the Native American Church obtained religious exemption from peyote restrictions in twenty-seven other states, though in a few instances, notably in a case before the Oregon Supreme Court, its arguments were rejected. Meanwhile, non-Native American requests for religious exemption from drug statutes have repeatedly been denied--including those of the Neo-American Church, which in 1968 claimed 20,000 members; the Universal Church of Christ Light, which used marijuana in its rituals; the Church of the Awakening, founded in 1963 by two retired osteopaths; the Native American Church of New York (of whose 1,000 members only a few were in fact Native Americans); Timothy Leary; and the Ethiopian Zion Coptic Church, a syncretic Jamaican group. Finally, in 1990, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the claim that the First Amendment protected the Native American Church's use of peyote--in part, no doubt, because of the obvious double standard that was being applied. Congress retaliated in 1993 with the

Religious Freedom Restoration Act, in effect reinstating both the Native American Church's right to use drugs in its religious rituals and the disturbing double standard.

The reasoning behind decisions that uphold the right to use drugs in a religious context is obvious: drugs play an important, even essential, role in the practice of many religious groups; the Constitution protects the free exercise of religious belief; therefore the Constitution protects the use of drugs. The reasoning behind decisions that reject the same right is that religious action, unlike religious belief, is not absolutely protected by the Constitution. The distinction was definitively articulated by Justice Owen Roberts in

Cantwell v.

Connecticut (1940).

"The [First] Amendment," he wrote, "embraces two concepts--freedom to believe and freedom to act. The first is absolute but, in the nature of things, the second cannot be." Thus the law, though it does not seek to prevent people from having certain religious beliefs, may prevent them from acting on those beliefs. Courts have held, for instance, that prohibitions on polygamy apply to Mormons, and that even Christian snake-handling sects are subject to regulations controlling the treatment of dangerous animals. Since taking drugs is an action, it is thus subject to government regulation.

But is this the right way to look at the situation? William James used drugs not because he had religious beliefs that encouraged him to do so but in order to

generate religious or mystical beliefs that he otherwise would not have had.

Looking back on my own experiences [with nitrous oxide], they all converge towards a kind of insight to which I cannot help ascribing some metaphysical significance. The keynote of it is invariably a reconciliation. It is as if the opposites of the world, whose contradictoriness and conflict make all our difficulties and troubles, were melted into unity. . . . This is a dark saying, I know, when thus expressed in terms of common logic, but I cannot wholly escape from its authority. I feel as if it must mean something, something like what the hegelian philosophy means, if one could only lay hold of it more clearly. Those who have ears to hear, let them hear; to me the living sense of its reality only comes in the artificial mystic state of mind.

If we take this claim seriously, and if we also take seriously Justice Roberts's assertion that the "freedom to believe" is absolute, then we need to rethink the prevailing consensus about religious drug use. Taking drugs is an action, certainly, but actions that are necessary for the production of religious beliefs should not be conflated with actions taken because of religious beliefs that could exist regardless. James needed nitrous oxide in order to have his mystical belief. Did he then have a constitutional right to use the drug? Just how absolute is the freedom to believe?

More important, James' philosophy gives us a principled way to think about the relation between religion and drugs. From a Jamesian perspective, religious toleration represents not just a commitment to individual freedom, not simply a hands-off policy on the part of the government toward questions of ultimate truth, but rather an affirmative decision to shelter certain useful though potentially false beliefs. Drug use, from this perspective, represents a similar sort of decision, but on the level of the individual rather than of the society. Just as a society might choose to nurture or tolerate certain sorts of illusions, pluralistically embracing both atheistic and religious subcultures, so, too, might an individual decide--as did James--to divide his or her life into periods of sober rationality and ecstatic religious intoxication. Drugs can allow even the most skeptical people, those who by constitution or upbringing are not susceptible to religious insights, to experience temporary periods of pleasing falsehood. Indeed, this is the real religious significance of drug use, from the Jamesian point of view--that it lets us choose, if only vaguely and temporarily, what to believe.

In 1977 Judge Jack Weinstein, of New York State, wrote,

Neither the trappings of robes, nor temples of stone, nor a fixed liturgy, nor an extensive literature or history is required to meet the test of beliefs cognizable under the Constitution as religious. So far as our law is concerned, one person's religious beliefs held for one day are presumptively entitled to the same protection as the beliefs of millions which have been shared for thousands of years.

These are generous words, and they should make us ask whether James' beliefs--held not for a day but for the mere minutes of his intoxication--warrant comparable charity. Can we learn to look at drug-induced illusion with enthusiastic Jamesian innocence? Is not the degree of self-control that pharmacology has given us remarkable? Prozac promises to change the hand that chemistry has dealt us, altering our moods to suit our needs. For James, drugs served a similar function: using nitrous oxide, he altered the beliefs that science had given him, experiencing if only for a brief time the pleasing illusions of the religious visionary.

Drugs, of course, are dangerous. They can destroy lives, families, and even whole communities. (James' own brother Robertson fought a long and losing battle with alcoholism.) The story of William James shows us how drugs can also contribute to human well-being, fulfilling in some instances an authentic religious need. Of course, our political culture is unprepared to recognize this. No doubt our courts will for the foreseeable future continue to deny that seekers like James might have a compelling religious interest in the use of drugs. Our politicians will continue to make perhaps unnaturally sharp distinctions: between the pleasing illusions of religious belief and those of intoxication; between the Native American's peyote and the non-Native American's nitrous oxide. A century after William James we have yet to catch up with him and his intoxicated nonsense.

Do drugs make religious experience possible? They did for James and for other philosopher-mystics of his day. James's experiments with psychoactive drugs raise difficult questions about belief and its conditions

www.theatlantic.com