Jabberwocky

Frumious Bandersnatch

- Joined

- Nov 3, 1999

- Messages

- 84,998

When ANNE-MARIE COCKBURN’s only child Martha died from an accidental ecstasy overdose, her world fell apart. Here she reveals how exchanging searingly honest letters with the young dealer who supplied the drug helped her cope with the pain

Eight months after losing her 15-year-old daughter, Anne-Marie Cockburn looked across a courtroom into the eyes of the boy who sold Martha’s friend the lethal drugs that killed her.

If she was hoping he would be given a long prison sentence, no one could have blamed her.

A single mother in her early 40s, Anne-Marie lost her entire world on 20 July 2013 when her only child collapsed and died after taking ecstasy.

There have been times since, she admits, when she has wondered how she can carry on without the bright, lively girl with whom she had shared everything, and in whose future her own was inextricably interwoven.

Martha loved music, especially Arctic Monkeys (her mum had just bought her a ticket to see them) and fashion (with a quirky twist), and she was bright (she had just taken two GCSEs early – Anne-Marie would collect her grades, an A and a B, after her death). Mother and daughter had travelled the world and had had fun together: they didn’t have a TV, so their evenings were spent chatting or playing board games.

But despite all she had lost with Martha’s death, the thoughts going through Anne-Marie’s mind were not of anger or revenge. She knew how young the boy in the courtroom was – just 17 – and she noticed he had brought a small bag with him into the dock. ‘I thought, he’s had to go through the emotions of packing a bag thinking he might be going to prison,’ she says. She had already decided it wasn’t what she wanted. ‘I knew a prison sentence would only make him more likely to get pulled into a life of crime,’ she says. ‘And my big hope was that he would find it in himself to make amends for what he had done. I felt very strongly that he owed it to Martha, and to me, to do that because it was the only fitting tribute to her, that he could turn his life around.’

Anne-Marie had already conveyed her feelings, via lawyers, to the judge; so she wasn’t surprised when the boy, Alex Williams, was told he would be spared prison and instead given a youth rehabilitation order, which meant he could continue going to college, and which would also have less of an impact on his future employment prospects.

His parents, who were in court, were clearly relieved, and Anne-Marie remembers it was all over very quickly. But over the next few days she realised that although she didn’t want Alex to be sent to prison, she did want something from him: she wanted a connection, an exchange. ‘I wanted to meet him,’ she says. ‘I wanted to know what this experience had been like for him. I wanted to know what he felt about Martha’s death.’

Alex and Martha never actually met but in July 2013 he had sold a friend of hers a gram of ecstasy, for which she had paid £40, later splitting it with Martha. But the powder was 91 per cent pure – far stronger than most of the drugs available in Britain – and when Martha took it with friends in a park two days later, she collapsed within minutes.

For Anne-Marie, it was every mother’s worst nightmare: while out shopping she noticed an unfamiliar number flashing up on her mobile; and then a stranger’s voice told her that her daughter was gravely ill, and that paramedics were doing all they could to save her. But Anne-Marie says that she knew the moment she saw Martha in casualty that she wasn’t going to make it, even though hospital staff were still desperately trying to revive her. ‘Fifteen years earlier I had brought my daughter into the world in that very same hospital and now, with a mother’s instinct, I knew she was leaving it,’ she remembers.

It was a harrowing, appalling loss; a loss so terrible, Anne-Marie thought afterwards, that there was no word to describe who she had now become: a single mother who had lost her only child. She wasn’t a widow, nor an orphan; she remained and always would be a mother, but now she had no living child.

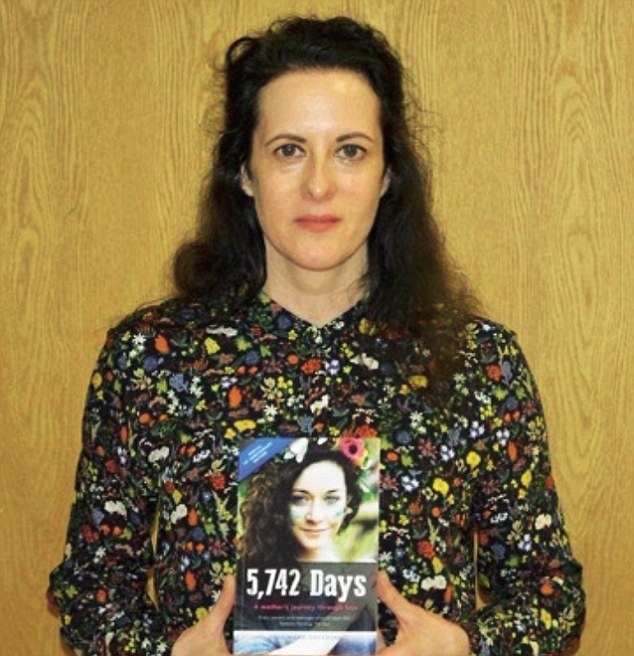

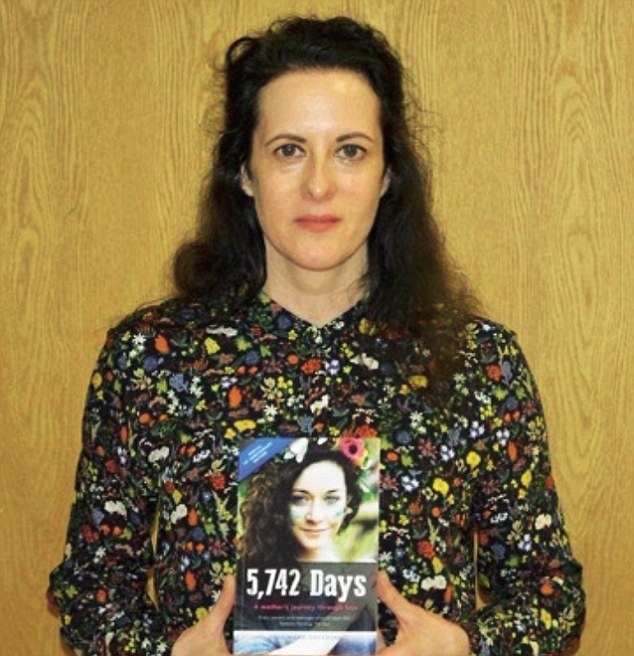

In a way the lack of a name was apt because the feeling of loss was indescribable: friends and family did what they could to support her but sometimes all she could do was cling on and get through the day. Some days she just stayed in bed; others she couldn’t get off the sofa. Work was impossible, but writing about and to Martha was the only thing that began to help. (Anne-Marie’s book 5,472 Days: A Mother’s Journey Through Loss was begun within hours of Martha’s death, and charts her grief in real time.)

In some ways you would think the very last person who could help her would be the boy who had caused her pain. But what Anne-Marie realised, to her surprise, was that he was perhaps the only person on the planet who could help her. So when a member of the youth offending team told her about the possibility of an exchange of letters with Alex under a scheme known as restorative justice, Anne-Marie knew this was something she wanted to happen.

The focus of restorative justice is the rehabilitation of offenders, a way of teaching them to appreciate the human cost of what they have done by enabling contact between a criminal and his or her victim. But it can also help victims by mitigating some of the psychological effects of crime.

‘It’s all done carefully, in a well-organised way, with staff from the youth offending team acting as the go-between,’ says Anne-Marie. Alex, who was living at home with his family in Oxford, was cooperative, and word came back via the team that he wanted to be in contact.

Not surprisingly, it turned out to be what she calls ‘a very intensive journey’. The first letter came from Alex. Its contents, says Anne-Marie, were carefully couched and neutral. ‘He didn’t say sorry,’ she says. ‘But then again, I believe sorry is an action, not a word. We say sorry so often and so easily in our culture. In other cultures they don’t say it so much, but there’s a view that you can tell by someone’s actions when they’re truly sorry. I like that approach.’

Anne-Marie has pledged never to reveal the exact contents of the letters – either his to her or hers to him – but about six letters passed in each direction. ‘And about halfway through the exchange, I realised there was a shift in the dialogue,’ she says. ‘I could see he had taken responsibility for what he had done and it was weighing heavily on his young shoulders. It showed me Martha’s death was not something he took lightly; and that for me was such an important moment because I realised I needed it to be acknowledged in a tangible way. I didn’t want Alex to suffer, but I did need him to acknowledge that Martha, my wonderful daughter, had lost her life. We’ve both suffered, me and Alex, and he told me in his letters that he felt devastated by what happened, and that it had a massive impact on his life. But what it came down to, what I really needed, was to know that he understood that a girl aged 15 had died, and that nothing could ever change that.’

From the outset, says Anne-Marie, she was acutely aware of Alex’s state of mind, and did everything she could not to tip him over the edge. ‘I was very conscious that I was the adult, he was very young and vulnerable. I was never angry in my letters; I was honest and straightforward. What I said was, life will never be the same again for me – which of course it won’t be, it can’t be.’

At the start of their correspondence, the idea was that Anne-Marie and Alex would eventually have a face-to-face meeting. ‘We talked about it in our letters, and I knew it would be a very important event for me,’ she says. ‘I had these big hopes that we could work together and do some good with what had happened to Martha. I thought we could make a big impact if the two of us told our stories, side by side.’

And then something happened that Anne-Marie had always known was a possibility given the proximity of their lives: she bumped into Alex in the supermarket. Or at least, she saw him – he didn’t notice her. ‘I knew it was him straight away, I remembered him from court,’ she says.

‘My first thought was, he looks like a nice young man. He didn’t see me and I was glad about that – it wasn’t the right moment to meet.’

The letters continued and, with just six weeks to go to the end of Alex’s 18-month supervision order, Anne-Marie wrote to say she wanted to go ahead with the meeting. ‘I told him, “I’m ready to meet you; I think it would help both of us.”’ But it was a blow when a member of the youth offending team came back with the message that Alex didn’t feel ready. It felt like a missed opportunity. ‘I think we could have helped one another a great deal. I respect him for writing to me and I know it can’t have been easy, but on the other hand, this was the one thing I ever asked of him, and in the end he turned me down.’

A realisation struck Anne-Marie. ‘I had this moment when I thought: it’s up to me to reconcile things inside myself. So I decided to close the door on the idea of meeting: “I’ve got to get on with my life. I don’t want any ambiguity.” So I told the team firmly: we will not meet. And now I know we never will. I felt my life had so much uncertainty in it at the time, and this was one thing I could control. He’d had his opportunity, and decided against it. For me it had to be finished so I could move on.’

But the experience of being in touch with Alex had changed things for Anne-Marie. She had always imagined them going into schools and prisons together, each telling their side of the story. ‘We would have been a very powerful team,’ she says. And now, if she couldn’t do it with Williams, she decided she would do it on her own, with the spirit of Martha by her side.

A few months later, Anne-Marie found herself in a prison for the first time in her life, talking to inmates and taking part in a restorative justice workshop run by The Forgiveness Project, an organisation that works in conflict resolution, reconciliation and victim support.

‘I was terrified,’ she remembers. ‘I was completely tense and stiff. But it was a life-changing experience: the thing about being in prison is that it’s human to human, everyone is very exposed emotionally. I had my book with me, with Martha’s picture on the front, and I told her story. When I looked round all these grown men – with hard faces and tattoos up their arms – were weeping. Afterwards some of them hugged me. One took my hand and said simply, thank you. Some said they had thought drug dealing was a victimless crime, just supply and demand – Martha’s story, they said, had shown them this wasn’t true.’

Today, three years after Martha’s death, Anne-Marie is helping to establish The Mint House, Oxford’s Centre for Restorative Practice and, as well as speaking in schools, she takes part in restorative justice workshops in prisons across Britain, working with prisoners to help them understand the impact of crime on victims’ lives.

But it’s a two-way process: what it’s all about, she says, is walking in one another’s shoes. She listens to the prisoners’ stories, just as they listen to hers. ‘So many prisoners have been raised in care, they’ve been neglected, they’ve had difficult lives,’ she says. ‘It doesn’t excuse what they’ve done, but it’s important to think about where they’ve come from, and not to judge them. And then they turn round and say things to me like, “I’m writing a poem for Martha.” I take Martha’s Converse trainers with me and I put them on a table in the middle of the room. That’s a powerful symbol – trainers are very important to prisoners, they’re among the few personal belongings they are allowed in prison and they’re about status, so that gives them extra resonance.’

Almost always, she says, there are prisoners who come up to her at the end of a session and say, that’s it, they’re never going to deal in drugs again. ‘And who knows,’ she says, ‘maybe they won’t.’ Recently, 50 female prisoners at Peterborough Prison were so moved by Martha’s story that they ran a sponsored mile for her, raising £800 for Anne-Marie’s charity, What Martha Did Next.

Today, Anne-Marie is devoted to the aims of promoting restorative justice and trying to reduce the harm caused to young people by illegal drugs. She backs a move by the House of Commons select justice committee to give all victims of crime the right to contact with offenders, since she knows from experience how cathartic and positive it can be. At the moment it’s offered piecemeal, but studies show it reduces the frequency of reoffending by 14 per cent, and Anne-Marie believes it also saves the NHS money in reducing long-term health risks to victims that can result from stress, depression and unresolved anger.

She recently moved house, and though it was searingly painful to have to sort through Martha’s belongings, she recognises that it was an important stage on her own onward journey. Living her life to the full, she says, is the best tribute she can give to Martha, and though it’s sometimes hard seeing Martha’s friends growing up, she is happy to see their lives moving on and pleased that she is still in touch with them. ‘They’re all going off to university now, and that’s what Martha should be doing,’ she says. ‘I have to allow myself a moment to grieve and to think how wonderful that would have been, but then I bring myself back to the present: my life must go on.’

One thing she doesn’t do when she’s visiting a prison is mince her words. ‘I tell them I was a mother of one; now I’m a mother of none.’ Without the realisation of what a difference Martha’s story could make, and without the chance to exchange those letters with Alex, Anne-Marie isn’t sure where she would be now. ‘The truth is, I believe restorative justice has saved me,’ she says. ‘I think if I hadn’t gone down this road, my family would have attended my own funeral by now. Realising the power of Martha’s story, and using it for change, has put something positive back into my life. And there’s very little positive you can get out of losing your only child, so that’s quite something.’

For more information on What Martha Did Next, and to make a donation to enable Anne-Marie to give talks in schools, go to whatmarthadidnext.org. For more details on the Forgiveness Project, visit theforgivenessproject.com

Source: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/you...sponsible-daughter-s-death.html#ixzz4PrYDYtJt

Eight months after losing her 15-year-old daughter, Anne-Marie Cockburn looked across a courtroom into the eyes of the boy who sold Martha’s friend the lethal drugs that killed her.

If she was hoping he would be given a long prison sentence, no one could have blamed her.

A single mother in her early 40s, Anne-Marie lost her entire world on 20 July 2013 when her only child collapsed and died after taking ecstasy.

There have been times since, she admits, when she has wondered how she can carry on without the bright, lively girl with whom she had shared everything, and in whose future her own was inextricably interwoven.

Martha loved music, especially Arctic Monkeys (her mum had just bought her a ticket to see them) and fashion (with a quirky twist), and she was bright (she had just taken two GCSEs early – Anne-Marie would collect her grades, an A and a B, after her death). Mother and daughter had travelled the world and had had fun together: they didn’t have a TV, so their evenings were spent chatting or playing board games.

But despite all she had lost with Martha’s death, the thoughts going through Anne-Marie’s mind were not of anger or revenge. She knew how young the boy in the courtroom was – just 17 – and she noticed he had brought a small bag with him into the dock. ‘I thought, he’s had to go through the emotions of packing a bag thinking he might be going to prison,’ she says. She had already decided it wasn’t what she wanted. ‘I knew a prison sentence would only make him more likely to get pulled into a life of crime,’ she says. ‘And my big hope was that he would find it in himself to make amends for what he had done. I felt very strongly that he owed it to Martha, and to me, to do that because it was the only fitting tribute to her, that he could turn his life around.’

Anne-Marie had already conveyed her feelings, via lawyers, to the judge; so she wasn’t surprised when the boy, Alex Williams, was told he would be spared prison and instead given a youth rehabilitation order, which meant he could continue going to college, and which would also have less of an impact on his future employment prospects.

His parents, who were in court, were clearly relieved, and Anne-Marie remembers it was all over very quickly. But over the next few days she realised that although she didn’t want Alex to be sent to prison, she did want something from him: she wanted a connection, an exchange. ‘I wanted to meet him,’ she says. ‘I wanted to know what this experience had been like for him. I wanted to know what he felt about Martha’s death.’

Alex and Martha never actually met but in July 2013 he had sold a friend of hers a gram of ecstasy, for which she had paid £40, later splitting it with Martha. But the powder was 91 per cent pure – far stronger than most of the drugs available in Britain – and when Martha took it with friends in a park two days later, she collapsed within minutes.

For Anne-Marie, it was every mother’s worst nightmare: while out shopping she noticed an unfamiliar number flashing up on her mobile; and then a stranger’s voice told her that her daughter was gravely ill, and that paramedics were doing all they could to save her. But Anne-Marie says that she knew the moment she saw Martha in casualty that she wasn’t going to make it, even though hospital staff were still desperately trying to revive her. ‘Fifteen years earlier I had brought my daughter into the world in that very same hospital and now, with a mother’s instinct, I knew she was leaving it,’ she remembers.

It was a harrowing, appalling loss; a loss so terrible, Anne-Marie thought afterwards, that there was no word to describe who she had now become: a single mother who had lost her only child. She wasn’t a widow, nor an orphan; she remained and always would be a mother, but now she had no living child.

In a way the lack of a name was apt because the feeling of loss was indescribable: friends and family did what they could to support her but sometimes all she could do was cling on and get through the day. Some days she just stayed in bed; others she couldn’t get off the sofa. Work was impossible, but writing about and to Martha was the only thing that began to help. (Anne-Marie’s book 5,472 Days: A Mother’s Journey Through Loss was begun within hours of Martha’s death, and charts her grief in real time.)

In some ways you would think the very last person who could help her would be the boy who had caused her pain. But what Anne-Marie realised, to her surprise, was that he was perhaps the only person on the planet who could help her. So when a member of the youth offending team told her about the possibility of an exchange of letters with Alex under a scheme known as restorative justice, Anne-Marie knew this was something she wanted to happen.

The focus of restorative justice is the rehabilitation of offenders, a way of teaching them to appreciate the human cost of what they have done by enabling contact between a criminal and his or her victim. But it can also help victims by mitigating some of the psychological effects of crime.

‘It’s all done carefully, in a well-organised way, with staff from the youth offending team acting as the go-between,’ says Anne-Marie. Alex, who was living at home with his family in Oxford, was cooperative, and word came back via the team that he wanted to be in contact.

Not surprisingly, it turned out to be what she calls ‘a very intensive journey’. The first letter came from Alex. Its contents, says Anne-Marie, were carefully couched and neutral. ‘He didn’t say sorry,’ she says. ‘But then again, I believe sorry is an action, not a word. We say sorry so often and so easily in our culture. In other cultures they don’t say it so much, but there’s a view that you can tell by someone’s actions when they’re truly sorry. I like that approach.’

Anne-Marie has pledged never to reveal the exact contents of the letters – either his to her or hers to him – but about six letters passed in each direction. ‘And about halfway through the exchange, I realised there was a shift in the dialogue,’ she says. ‘I could see he had taken responsibility for what he had done and it was weighing heavily on his young shoulders. It showed me Martha’s death was not something he took lightly; and that for me was such an important moment because I realised I needed it to be acknowledged in a tangible way. I didn’t want Alex to suffer, but I did need him to acknowledge that Martha, my wonderful daughter, had lost her life. We’ve both suffered, me and Alex, and he told me in his letters that he felt devastated by what happened, and that it had a massive impact on his life. But what it came down to, what I really needed, was to know that he understood that a girl aged 15 had died, and that nothing could ever change that.’

From the outset, says Anne-Marie, she was acutely aware of Alex’s state of mind, and did everything she could not to tip him over the edge. ‘I was very conscious that I was the adult, he was very young and vulnerable. I was never angry in my letters; I was honest and straightforward. What I said was, life will never be the same again for me – which of course it won’t be, it can’t be.’

At the start of their correspondence, the idea was that Anne-Marie and Alex would eventually have a face-to-face meeting. ‘We talked about it in our letters, and I knew it would be a very important event for me,’ she says. ‘I had these big hopes that we could work together and do some good with what had happened to Martha. I thought we could make a big impact if the two of us told our stories, side by side.’

And then something happened that Anne-Marie had always known was a possibility given the proximity of their lives: she bumped into Alex in the supermarket. Or at least, she saw him – he didn’t notice her. ‘I knew it was him straight away, I remembered him from court,’ she says.

‘My first thought was, he looks like a nice young man. He didn’t see me and I was glad about that – it wasn’t the right moment to meet.’

The letters continued and, with just six weeks to go to the end of Alex’s 18-month supervision order, Anne-Marie wrote to say she wanted to go ahead with the meeting. ‘I told him, “I’m ready to meet you; I think it would help both of us.”’ But it was a blow when a member of the youth offending team came back with the message that Alex didn’t feel ready. It felt like a missed opportunity. ‘I think we could have helped one another a great deal. I respect him for writing to me and I know it can’t have been easy, but on the other hand, this was the one thing I ever asked of him, and in the end he turned me down.’

A realisation struck Anne-Marie. ‘I had this moment when I thought: it’s up to me to reconcile things inside myself. So I decided to close the door on the idea of meeting: “I’ve got to get on with my life. I don’t want any ambiguity.” So I told the team firmly: we will not meet. And now I know we never will. I felt my life had so much uncertainty in it at the time, and this was one thing I could control. He’d had his opportunity, and decided against it. For me it had to be finished so I could move on.’

But the experience of being in touch with Alex had changed things for Anne-Marie. She had always imagined them going into schools and prisons together, each telling their side of the story. ‘We would have been a very powerful team,’ she says. And now, if she couldn’t do it with Williams, she decided she would do it on her own, with the spirit of Martha by her side.

A few months later, Anne-Marie found herself in a prison for the first time in her life, talking to inmates and taking part in a restorative justice workshop run by The Forgiveness Project, an organisation that works in conflict resolution, reconciliation and victim support.

‘I was terrified,’ she remembers. ‘I was completely tense and stiff. But it was a life-changing experience: the thing about being in prison is that it’s human to human, everyone is very exposed emotionally. I had my book with me, with Martha’s picture on the front, and I told her story. When I looked round all these grown men – with hard faces and tattoos up their arms – were weeping. Afterwards some of them hugged me. One took my hand and said simply, thank you. Some said they had thought drug dealing was a victimless crime, just supply and demand – Martha’s story, they said, had shown them this wasn’t true.’

Today, three years after Martha’s death, Anne-Marie is helping to establish The Mint House, Oxford’s Centre for Restorative Practice and, as well as speaking in schools, she takes part in restorative justice workshops in prisons across Britain, working with prisoners to help them understand the impact of crime on victims’ lives.

But it’s a two-way process: what it’s all about, she says, is walking in one another’s shoes. She listens to the prisoners’ stories, just as they listen to hers. ‘So many prisoners have been raised in care, they’ve been neglected, they’ve had difficult lives,’ she says. ‘It doesn’t excuse what they’ve done, but it’s important to think about where they’ve come from, and not to judge them. And then they turn round and say things to me like, “I’m writing a poem for Martha.” I take Martha’s Converse trainers with me and I put them on a table in the middle of the room. That’s a powerful symbol – trainers are very important to prisoners, they’re among the few personal belongings they are allowed in prison and they’re about status, so that gives them extra resonance.’

Almost always, she says, there are prisoners who come up to her at the end of a session and say, that’s it, they’re never going to deal in drugs again. ‘And who knows,’ she says, ‘maybe they won’t.’ Recently, 50 female prisoners at Peterborough Prison were so moved by Martha’s story that they ran a sponsored mile for her, raising £800 for Anne-Marie’s charity, What Martha Did Next.

Today, Anne-Marie is devoted to the aims of promoting restorative justice and trying to reduce the harm caused to young people by illegal drugs. She backs a move by the House of Commons select justice committee to give all victims of crime the right to contact with offenders, since she knows from experience how cathartic and positive it can be. At the moment it’s offered piecemeal, but studies show it reduces the frequency of reoffending by 14 per cent, and Anne-Marie believes it also saves the NHS money in reducing long-term health risks to victims that can result from stress, depression and unresolved anger.

She recently moved house, and though it was searingly painful to have to sort through Martha’s belongings, she recognises that it was an important stage on her own onward journey. Living her life to the full, she says, is the best tribute she can give to Martha, and though it’s sometimes hard seeing Martha’s friends growing up, she is happy to see their lives moving on and pleased that she is still in touch with them. ‘They’re all going off to university now, and that’s what Martha should be doing,’ she says. ‘I have to allow myself a moment to grieve and to think how wonderful that would have been, but then I bring myself back to the present: my life must go on.’

One thing she doesn’t do when she’s visiting a prison is mince her words. ‘I tell them I was a mother of one; now I’m a mother of none.’ Without the realisation of what a difference Martha’s story could make, and without the chance to exchange those letters with Alex, Anne-Marie isn’t sure where she would be now. ‘The truth is, I believe restorative justice has saved me,’ she says. ‘I think if I hadn’t gone down this road, my family would have attended my own funeral by now. Realising the power of Martha’s story, and using it for change, has put something positive back into my life. And there’s very little positive you can get out of losing your only child, so that’s quite something.’

For more information on What Martha Did Next, and to make a donation to enable Anne-Marie to give talks in schools, go to whatmarthadidnext.org. For more details on the Forgiveness Project, visit theforgivenessproject.com

Source: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/home/you...sponsible-daughter-s-death.html#ixzz4PrYDYtJt