mr peabody

Bluelight Crew

- Joined

- Aug 31, 2016

- Messages

- 5,714

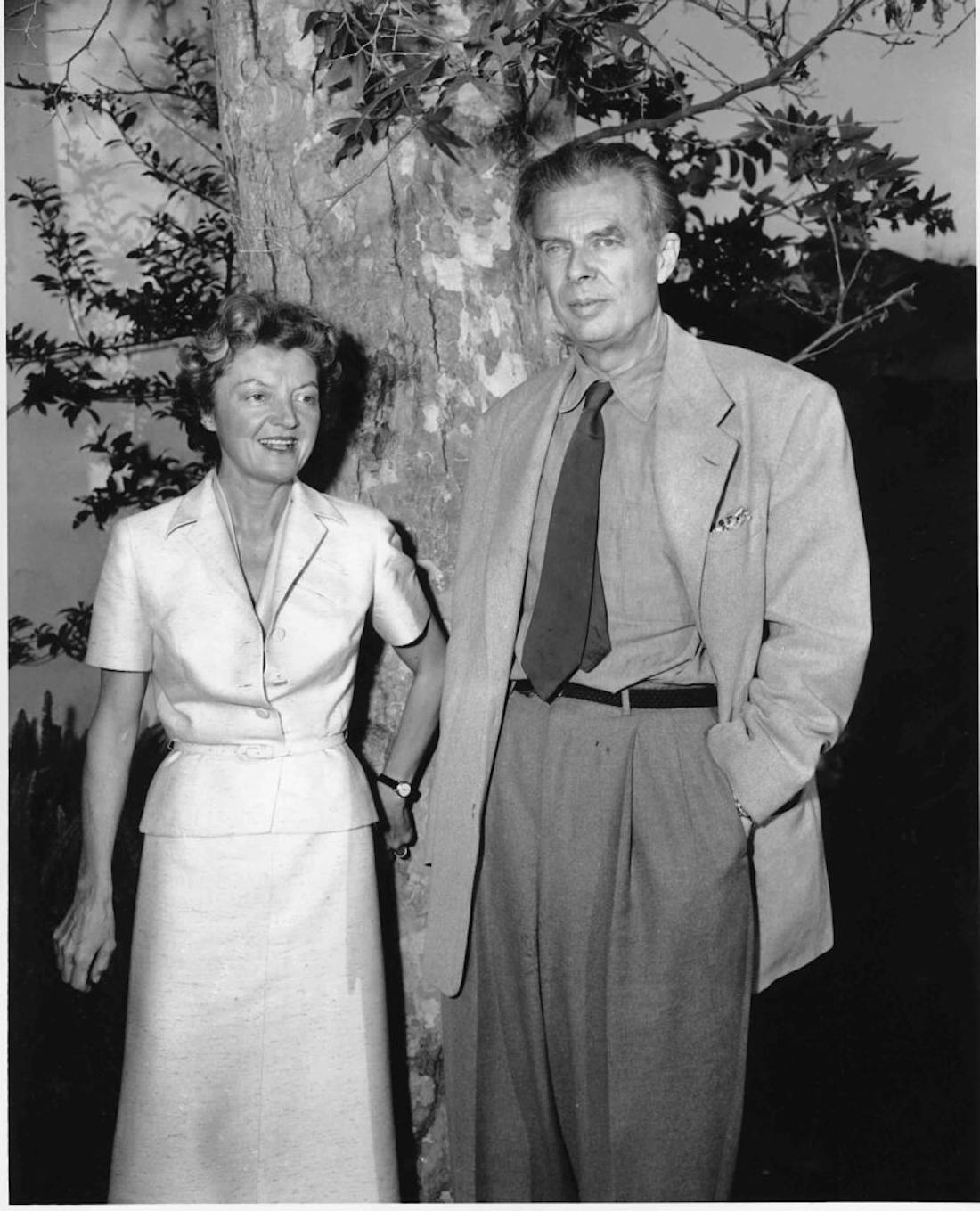

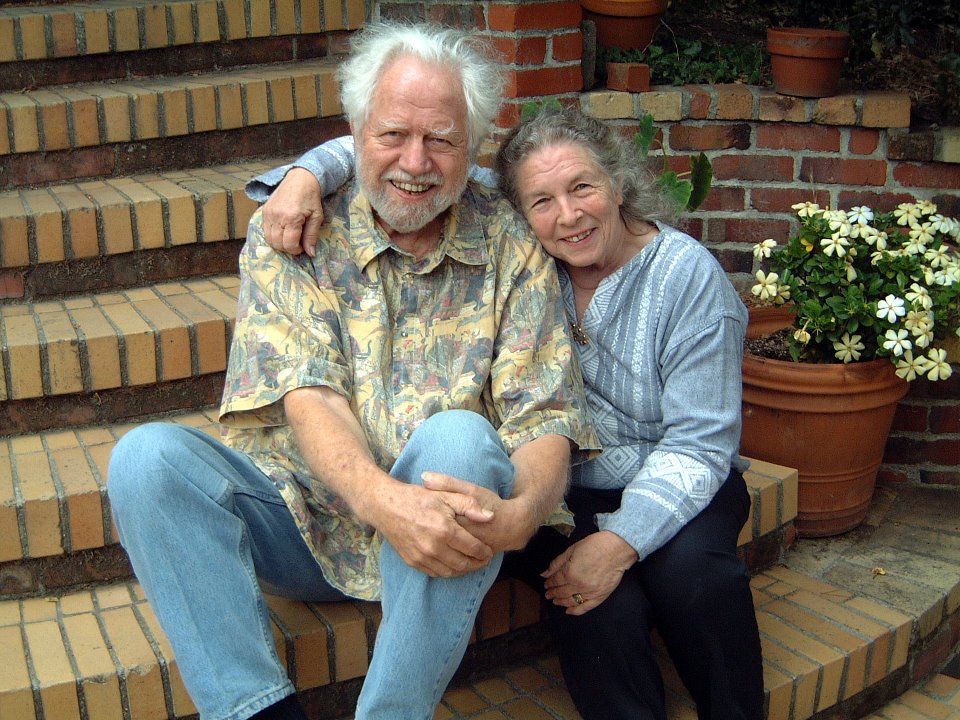

Ann and Alexander Shulgin

Psychedelics in Palliative Care

by Mellody Hayes | Scientific American | 20 March 2020

Drugs that foster feelings of uplift and connection can be therapeutic for many conditions in many phases of life.

After my presentation at a psychedelic science conference, a young professional woman approached me to share her moving story of healing and recovery from depression after participating in ketamine-assisted psychotherapy.

She explained she had languished in depression for 12 years, feeling trapped by fears and insecurity. She smiled, her lips painted a flirty fuchsia, and she seemed to embody her newfound freedom. No longer languishing in bed, she described that the shackles were off and she was free.

Her inspiring story of healing is strikingly common in the world of psychedelic medicine research, and one that has broader implications across the lifespan.

As an anesthesiologist with a focus on palliative care and psychedelic medicine, I recently shared my own story of healing at the summit at Headlands Center for the Arts on psychedelic medicine and palliative care.

Following medical treatment with ketamine, I was able to recover from physician burnout and achieve deeper relational healing. As the founder of Ceremony Health, I shared details about the center’s group therapy, healing rituals, and ketamine therapy for those experiencing fear in the face of a new life-changing medical diagnosis or seeking recovery from anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and social isolation.

During the summit, many conversations ground into a well-worn groove: “How do we explain to the public that palliative care is about living, not merely about death and dying?”

Branding is a frequent topic because many associate the speciality of palliative care only with the end of life. Perhaps that is because some remain unaware that, as experts in symptom management, palliative care physicians can provide quality of life improvement for those with long-term debilitating illnesses over their lifetimes.

If a person is gravely ill, they can seek a referral for a palliative care specialist who can offer so much to the process—trying to optimize joy, not merely treat an illness.

Palliative care–supportive treatment focused on increasing wellness and reducing symptoms can actually provide better survival rates than traditional cancer care. Researchers in one 2010 combined study out of Massachusetts General Hospital, Columbia and Yale found that despite not having aggressive lung cancer treatment, those who received palliative care lived nearly three months longer than those who did have cancer treatments.

Yes, the specter of death haunts the field. But once in palliative care, patients often report that it is the care they wished they had all along.

Patients report increased satisfaction with care and improved quality of life. A meta-analysis published in 2018 even found that palliative care decreases the cost of health care, with hospitals saving an average of $3,237 per patient per hospital stay.

With care that is holistic, supportive, a bit less rushed and often offered by clinicians with keen communication skills, patients may also find refuge. A patient may find a receptive and healing audience for their cultural, spiritual, and emotional needs during illness.

B.J. Miller, a practicing palliative care physician at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center and co-author with Shoshana Berger of A Beginner's Guide To The End, told conference participants, “Over time it becomes less about talking about the symptom inventory and just a dance to get to the hug at the end of the visit.”

Getting to the hug may become easier as Federal Drug Administration trials for psychedelic medicines for end-of-life anxiety approach completion. Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research is in phase III clinical trials to approve psilocybin for market as a prescription medication.

The FDA has given MDMA, designation as a breakthrough therapy. It is also in phase III of its clinical trials, the last phase before going to market as a prescription.

Colloquially, providers refer to psilocybin as magic mushrooms. New research is confirming its potency by showing that cancer patients treated just once with psilocybin experienced treatment benefits present five years later.

For those with anxiety in the face of a new illness diagnosis, treatment with psychedelic medicine provided relief from anxiety, allowing patients the capacity to engage with their medical care with more presence and purpose.

Additional treatment frontiers for psychedelic medicine include Alzheimer's dementia, anorexia, and opioid use disorder as more researchers conduct studies to evaluate additional treatment indications.

Although these psychedelic medications are generally considered physiologically safe, health care providers and patients should not underestimate their potency. They may not be appropriate for persons with a diagnosis of psychosis, and counselors with training in psychedelic care need to be involved in treatment with patients prescribed these drugs.

It’s important to understand that although psychedelic medicines are swiftly effective, the psychological changes patients experience during treatment may be daunting to some. The experience of treatment, often called “a journey,” takes courage because one may discover the shadows of one's own psychology. Some report intensely increased sensitivity to sensation.

A police officer who said he experienced underground treatment with psychedelic medicine shuddered as he recalled the experience, saying he should have been warned that he would be able to feel even the air on his skin.

For some who struggle with mental illness, treatment with psychedelic medicine may not be about living well with illness; it may provide some with a treatment that allows them to live free from illness.

For example, research shows that MDMA-assisted psychotherapy has a 76 percent success rate for patients with post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, measured by remission one year after treatment.

For people trying to quit smoking, treatment with psilocybin helped 80 percent of people stay smoke-free six months after treatment, while traditional treatments are only effective for 10–35 percent of people. And robust clinical research is rehabilitating the reputation of the previously maligned “hippie” drug LSD as study results demonstrate its efficacy in treating end-of-life anxiety and alcoholism.

These “hug drugs,” as empathogenic (empathy creating) medications are called, often provide rapid transformation from pain and grief into wellness and emotional health, from isolation and sadness into connection and appreciation. It can also be transformation that lasts.

The transformation, hope and engagement in purpose that patients who undergo psychedelic treatment experience as a part of their palliative care contributes to their wellness. This may also help end the branding problem of palliative care.

As more patients in palliative care report feeling uplifted, connected and hopeful, perhaps it is time to change the name of the field to magic medicine.

Psychedelics in Palliative Care

Drugs that foster feelings of uplift and connection can be therapeutic for many conditions in many phases of life

Last edited: