mr peabody

Bluelight Crew

- Joined

- Aug 31, 2016

- Messages

- 5,714

Rethinking therapeutic strategies for Anorexia Nervosa: Insights from psychedelic medicine*

Claire Foldi, Paul Liknaitzky, Martin Williams, Brian Oldfield

Anorexia nervosa (AN) has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disease, yet available pharmacological treatments are largely ineffective due, in part, to an inadequate understanding of the neurobiological drivers that underpin the condition. The recent resurgence of research into the clinical applications of psychedelic medicine for a range of mental disorders has highlighted the potential for classical psychedelics, including psilocybin, to alleviate symptoms of AN that relate to serotonergic signaling and cognitive inflexibility. Clinical trials using psychedelics in treatment-resistant depression have shown promising outcomes, although these studies are unable to circumvent some methodological biases. The first clinical trial to use psilocybin in patients with AN commenced in 2019, necessitating a better understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms through which psychedelics act. Animal models are beneficial in this respect, allowing for detailed scrutiny of brain function and behavior and the potential to study pharmacology without the confounds of expectancy and bias that are impossible to control for in patient populations. We argue that studies investigating the neurobiological effects of psychedelics in animal models, including the activity-based anorexia (ABA) rodent model, are particularly important to inform clinical applications, including the subpopulations of patients that may benefit most from psychedelic medicine.

The resurgence of psychedelic medicine and therapeutic potential for AN

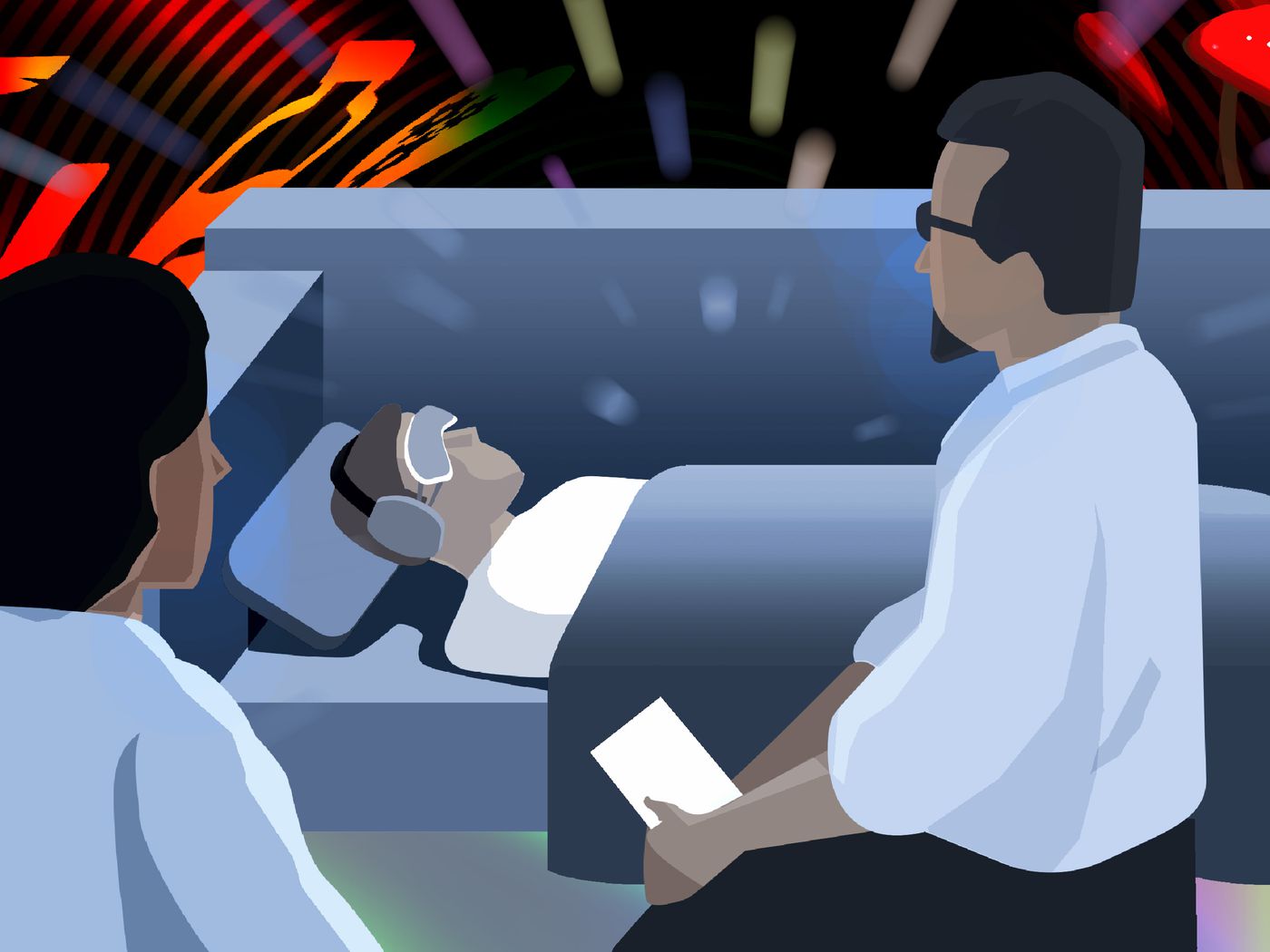

Psychedelics were first investigated as therapeutic agents for mental disorders in the 1950s and more than 1000 clinical papers were published on classical psychedelics between 1950 and the mid-1960s. However, political concerns over widespread non-clinical use and governmental interventions associated with an emerging counter culture led to regulatory obstacles and an abrupt end to this promising research. Recently, a resurgence of research into the clinical application of psychedelics has emerged and clinical trials have already highlighted psychedelic medicine as a promising alternative to conventional methods in what is being hailed as a “paradigm shift” for the treatment of psychiatric disorders, including depression, post-traumatic stress and substance use disorders. In addition, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have twice designated psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression as a “breakthrough therapy,” in 2018 and 2019. Combined with specialized psychotherapy, psilocybin has been shown to decrease symptoms of anxiety and depression that accompany life-threatening cancer diagnoses, alleviate symptoms in patients with treatment-resistant depression, and improve adherence to abstinence regimes in nicotine-dependent smokers. Moreover, patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) have shown short-term improvements following psilocybin treatment.

Multiple studies investigating the safety and efficacy of psilocybin for the treatment of major depressive disorder have recently commenced across the U.S. and Europe. Importantly, the first Phase 1 study exploring the safety and efficacy of psilocybin in patients with AN was launched in 2019 to examine a range of outcome measures including self-reported anxiety, depression and quality of life as well as changes in body mass index (BMI) and food preference. The findings from this trial will indicate efficacy one way or the other; however, understanding the biological mechanisms that underpin any effects of psilocybin on AN await carefully controlled clinical and animal-based studies. It should be noted that preliminary support for the efficacy of psychedelics on eating disorder symptoms has been shown in qualitative interviews with patients following the ceremonial consumption of ayahuasca, another serotonergic psychedelic.

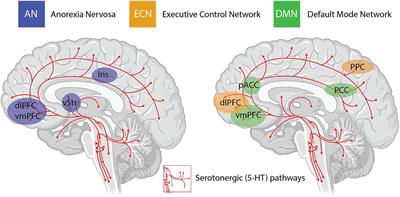

An important consideration when interpreting the findings from clinical trials using psychedelics is the inability to circumvent certain methodological biases. Even when niacin or very low dose psychedelics are used as active placebos, most participants and therapists are quickly unblinded to the condition, potentially resulting in expectancy biases. The subjective scales used to measure the efficacy of psilocybin in some studies introduces further bias in the assessment of outcome measures. Irrespective of these limitations, the neurobiological “mechanisms” underlying the efficacy of psychedelics for treatment-resistant depression are beginning to be elucidated in very broad terms through administration of psilocybin in combination with brain imaging techniques. The insights with the most experimental support include alterations in activity and functional connectivity within the default mode network (DMN), a group of neural structures that represent resting-state cognition. Functional connectivity between the DMN and other resting state networks is generally shown to increase following administration of psilocybin, and unusual levels of co-activation between DMN and task-positive structures has been found under psilocybin and ayahuasca. The mechanisms underlying the action of psilocybin on functional activity in resting state networks remain poorly understood, particularly the role of the serotonergic system, considering that the major midbrain nucleus in which 5-HT cell bodies lie is not included in canonical resting state networks. Regardless, mechanistic models have been developed that assert the action of psychedelics as relaxing high-level prior beliefs and liberating bottom-up information flow, and progress is being made to explain the action of psychedelics in the context of complicated neurotransmitter pharmacology, molecular pathways, and plastic changes that contribute to the central actions of these compounds.

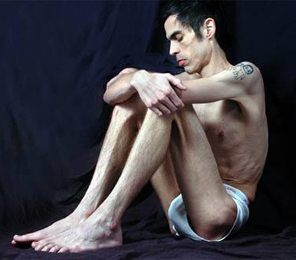

Anorexia nervosa (AN) has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder and is characterized by a relentless pursuit of weight loss despite severe emaciation. The majority of patients with AN also engage in excessive physical exercise and other compulsive locomotor strategies to avoid or counteract weight gain. A number of brain imaging studies in AN point to a combination of decreased neural activity in ventral reward regions and increased neural activity in prefrontal control regions. This imbalance may underlie the rigid adherence to punishing diet and exercise regimes by patients with AN that is characterized by both excessive behavioral control and diminished cognitive flexibility. Despite the high mortality and the array of pharmacological and psychotherapeutic strategies that have been employed to treat AN, up to 50% of AN patients suffer with chronic, often life-long illness, indicating that therapeutic strategies remain inadequate in treating the core symptoms of the disorder. In this respect, psychedelic medicine in combination with specialized psychotherapy represents a novel therapeutic strategy to treat disorders such as AN where treatment options have historically languished.

The purpose of this review is to highlight the potential suitability of psychedelic medicine for improving long-term treatment outcomes in AN, based on what is known about 5-HT signaling and cognitive function in patients and animal models. Although much of our argument is likely to be applicable to the therapeutic potential of other serotonergic or “classical” psychedelic compounds, including LSD and ayahuasca, we focus here on psilocybin for three reasons: (1) the two FDA designations as a “breakthrough therapy” for treatment-resistant depression; (2) its prevailing use in numerous clinical trials for mental disorders; and therefore (3) the proximity to approval as the first widely used psychedelic in medicine and therapy. Further, we argue that fundamental research in animal models is necessary to reach a comprehensive understanding of the therapeutic effects of psychedelics in psychiatric disease. This is no different to the genesis and clinical acceptance of virtually every other pharmaceutical approach; however, in this instance the use of animal experimentation has the profound advantage of eliminating context and expectation that introduce confounds in the understanding of the neurobiological and pharmacological actions of psychedelic compounds.

The neurobiological actions of psilocybin and relevance to AN

Although it is well known that psilocybin, or more specifically its active metabolite, psilocin, acts as an agonist at multiple serotonergic sites, including the 5-HT2A, 5-HT1A, and 5-HT2C receptors, focus has centered on the 5-HT2A receptor binding profile of psilocin due to the finding that specific 5-HT2A antagonists (e.g., ketanserin) block the majority of subjective effects of the drug in human subjects and psilocybin-induced discrimination learning in mice. Psilocybin intake results in dose-dependent occupancy of the 5-HT2A receptor in the human brain, and both plasma psilocin levels and 5-HT2A binding are closely associated with subjective ratings of the intensity of psychedelic experiences.

The other major neurobiological action of psilocybin administration is to decrease activity and functional connectivity within the DMN, a resting state network that is activated during higher-order cognitive tasks, such as considerations of past and future, self-referential cognition as well as personal, social and moral judgments or decision-making. Interestingly, resting state functional connectivity between the executive control network (ECN), a task-positive network primarily involved in cognitive control and emotional processing, and the anterior cingulate cortex is decreased in drug-naïve adolescents developing AN compared to healthy controls. During demanding cognitive tasks, the ECN typically shows increased activation, whereas the DMN shows decreased activation. Moreover, the insula, a brain region that plays a critical role in switching between the ECN and DMN in divergent thinking shows disrupted connectivity in patients with AN. Accordingly, it may be that psilocybin could act to shift cognitive processing away from an excessive internal focus and toward a more appropriate contextual balance. This style of information processing can more easily adapt to changing environmental needs, perhaps addressing aspects of cognitive inflexibility in patients with AN.

Effects of psilocybin in animal models

The behavioral effects of psilocybin in animal models appear to be mediated primarily through agonism of the 5-HT2A receptor, because the primary behavioral readout in response to psychedelics in rodents, the head-twitch response (HTR), is absent in mice lacking the 5-HT2AR gene. The other most frequent unconditioned behavioral responses to psychedelics in rodents are disruptions to sensorimotor gating (PPI) and exploratory behavior. Psilocybin also impacts associative learning in animal models by preventing rats from acquiring conditioned avoidance responses and producing more rapid extinction of conditioned fear responses in mice. In addition, psilocybin has been shown to induce dopamine (DA) release in the nucleus accumbens (part of the ventral striatum) and increase extracellular 5-HT levels in the medial prefrontal cortex in rats. This finding is tantalizingly consistent with the proposal that psilocybin could alleviate anorexic symptoms in the ABA model, not only because 5-HT signaling is reduced during ABA, but also because selective activation of DA projections to the nucleus accumbens prevents and rescues the ABA phenotype.

Studies investigating the therapeutic potential of psilocybin in animal models of psychiatric disease have demonstrated significant alleviation of symptoms in mouse models of OCD and PTSD, but did not significantly reduce anxiety phenotypes in wildtype rats or depression-related behavior in a genetic rat model, the Flinders Sensitive Line (FSL). There are several reasons why the significant abatement of depression and anxiety symptoms in human clinical trials was not replicated in these animal studies. It may be that the behavioral test of depression in rodents, the Forced Swim Test (FST), does not fully capture the pathological state of major depressive disorder that is amenable to psilocybin treatment. The FST was originally developed as an antidepressant drug screen and aided the discovery of multiple drugs used successfully in the treatment of clinical depression. However, the behavior of rats and mice in this test is influenced by a number of factors including stress and activity levels, and immobility in this task has been suggested to reflect both adaptive behavior as well as despair. Similarly, although FSL rats are shown to respond to traditional antidepressant medications, they also have markedly lower expression of 5-HT2A receptor mRNA in the frontal cortex, indicating that perhaps the 5-HT2A-mediated effects of psilocybin may have a blunted response in these animals, driven by an inability to bind. This study did not examine the impact of psilocybin on brain function or receptor-specific activity, so whether depressive phenotypes in the FSL model correlate with altered 5-HT2A signaling remains to be resolved.

It is also likely that at least part of the impact of psilocybin on treatment-resistant depression in clinical trials is driven by the higher order subjective characteristics of psychedelic-assisted therapy and the known role of context in the efficacy of psychedelics. Indeed, certain subjective effects are shown to be critical for long-term clinical outcomes across multiple trials. Regardless, it remains the case that ethologically relevant animal models with specific neurobiological and behavioral features that are known to be amenable to the neurobiological impacts of psilocybin will provide unique insight into the therapeutic potential of psychedelics. One example is the ABA model, that displays both cognitive rigidity and disrupted 5-HT function analogous to the human condition. Such studies should test cognitive function in comparable ways to human cognitive test batteries, differentiate effects of single dose administration versus repeated dosing and investigate the impact of non-psychedelic 5-HT2A agonists to challenge the specificity of the effects of psilocybin on behavior and brain function.

Summary and conclusion

Recent clinical trials have put the spotlight on the therapeutic potential of psychedelics, specifically psilocybin, for a range of psychiatric disorders. The neurobiological and behavioral phenotype of AN, specifically with respect to modified serotonergic signaling and cognitive inflexibility, is well-positioned to be impacted by the putative effects of psilocybin treatment. New treatment strategies for AN are urgently needed, considering that up to 50% of patients with AN never recover, and the risk of death in patients with AN is more than five times higher than in the general population. Converging evidence suggests that psilocybin may be a promising novel treatment for AN, and well-designed trials including those in established animal models are warranted.

Surprisingly, beyond animal testing for safety and tolerability, the psychedelic research model has thus far largely bypassed the comprehensive screening of drug effects in animal models that usually punctuates the drug discovery pipeline to clinical trials in human patients. This may be based on the premise that psychedelic drugs will not impact animals in the same way as humans because of the uniqueness of the notable phenomenology in humans. Regardless, certain underlying neurobiological effects of psychedelics on cognitive function can be interrogated in animal models with much greater specificity than in human subjects. Animal models of disease also allow determination of the neurobiological effects of psychedelic drugs without the confounds of expectancy and bias that are impossible to control for in patient populations. They have been used successfully over many decades to enable rational pharmacology and the development of more targeted and efficacious medications.

The knowledge gained from animal studies of psychedelic medicines will add substantially to mechanistic accounts of clinical treatments for humans, and may afford improvements and innovations in clinical treatment. The important contribution that animal models can make in progressing the understanding (and possibly development) of psychedelic medicine as a viable therapeutic approach to some mental disorders is in the detailed scrutiny of brain function and behavior they provide. This aligns with a well-worn path whereby detailed mechanistic insights enable rational drug design. However, there is another less tangible benefit that may arise from a better, experimentally based understanding of the actions of psilocybin; reducing stigma associated with the use of psychedelics in a clinical setting. Across a wide range of community attitudes and social bias, it is increasingly recognized that education and understanding are key elements in dismantling stigma. Specifically, a reductionist understanding of the brain circuitry and neurochemistry that mediate the central effects of psychedelic medicines – independent of the confounds of human expectations and context – will help to demystify their clinical effects and hopefully diminish the prejudice associated with their use in the treatment of psychiatric disorders such as AN.

*From the article here :

Rethinking Therapeutic Strategies for Anorexia Nervosa: Insights From Psychedelic Medicine and Animal Models

Anorexia nervosa (AN) has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disease, yet available pharmacological treatments are largely ineffective due, in part, to an inadequate understanding of the neurobiological drivers that underpin the condition. The recent resurgence of research into the...

Last edited: