Here's a gift link to the article.

A few thoughts. I am someone who got clean from heroin in 2008, was homeless at that time, and who has worked in some version of MAT/OBAT/Harm Reduction space since 2010 (and as a public health social worker since 2012). I believe in and have supported a supervised consumption effort locally, serving in an advisory capacity to one such effort in the city I live in. I have seen the positive benefits that access to naloxone, buprenorphine, and even things as basic as syringe exchange, can have for drug users. I cannot imagine what fentanyl would have been like if it manifested this way in the 90s, when Narcan was not widely available and buprenorphine was sitting on a shelf somewhere. Obviously, these things all happen as a reaction/response to one another, but suffice to say, people who use drugs would be far more vulnerable to fatal overdose without access, and far more vulnerable to Hep and HIV without clean needles.

i also think about the folks I've worked with who used opioids for 2 years, and have been on buprenorphine for 8. Stuck in a gray limbo of semi-monthly visits, prior authorizations, urine tox screens, and clinic waiting rooms. I think about the patients who rely on an increasingly overburden public health infrastructure for things like public transportation passes, dunkin donuts gift cards, and human connection. I've seen the urgency that is so present in early recovery fade into a sort of suspended malaise as the years go on, 16-24mg/day at a time. A friend and former colleague who has been prescribing suboxone since it was brand name only said it best: "we can get people on it no problem, but we're terrible at getting people off of it". For a long time, I felt like it was because of the protracted and unpredictable withdrawals that people experienced, but that began to change when we started seeing how well sublocade did as a long-term withdrawal aid.

We had some folks who were in the initial trials for the long-acting injectable, and a couple of them ended up doing short sentence jail time (6-9 months) following their enrollment. Once in jail, they weren't able to get their monthly injection. When we saw them again, a few things were really interesting to me. First, several still had bupe in their urine screens, 6 months post injection. Additionally, they hadn't gotten sick. They felt fine. As the health center I worked at at that time began the process of getting credentialed to order and supply sublocade, I would talk with some of my patients who had professed their longing to be free of bupe about how it seemed like their miracle drug had arrived. At first, a few even took us up on it, were able to detox, and moved on with their lives. Some returned back after a relapse, or feeling 'vulnerable' without the drug in their system.

Part of why all of this bothers me, is that I rarely see true success stories. I hear about them, and sometimes I've even had a patient who has been one. Most of the time, the patients I see that are successful on buprenorphine, seem to achieve about (a ballpark/arbitrary measurement) a 60% improvement in their life from when they were using. They're stable, not at risk of overdose, and are engaged in health care. They're able to hold down jobs, and not ruin relationships. These are all good things. The thing is, there's a certain degree of volition that seems lost to buprenorphine. People that are successful seem to stay in the system, and years go by without much progress further. This is despite the vast majority of people indicating at intake that "they don't want to go on this forever". I personally think that some of this is pharmacological in nature, that there is a pacifying effect that opioids create, which lingers in a subconscious way. It's also systemic, a long-term successful and stable patient is going to consistently show up for billable visits, is going to provide urine screen and pharmacy revenue, and is going to require minimal care coordination. These patients are viewed as easy to manage, though their suffering is often the hardest to notice, treat, or reach. I think some of it also comes from the destigmatization of addiction in ways that can actually be harmful to people's wellbeing.

I believe we need to destigmatize addiction, drug use, and people who use drugs. I am open about who I am as a person and as a clinician. I do think that people who have experienced addiction can find ways to have a healthier relationship with *some* drugs. I also know that for me it has taken, and continues to take, work and personal accountability to balance using any substances with the part of me that fell inlove with drug use in my teens and 20s. I stay away from certain classes of drugs, certain routes of administration, and have rules that I follow for myself. I have people in my life that I talk with about my substance use. I have to be honest and do a lot of soul searching when I run into a challenge or a consequence that is related to my choice to use substances. I take time off - 'dry january' has become an annual tradition with my wife. I do these things so that I can leave the option open to use things like mescaline, MXiPr, alcohol, and dexamphetamine. I limit any opioid use to kratom except during my first bout with covid this fall. I talked with my PCP about the painful cough I was experiencing, and asked for an Rx for tussionex. She's aware of my history with addiction, and I was up front that I had a plan, would take only as prescribed, and would check in with others about it. It's important to me to have these rules in place because if I don't, I have seen my life devolve into painful and destructive chaos.

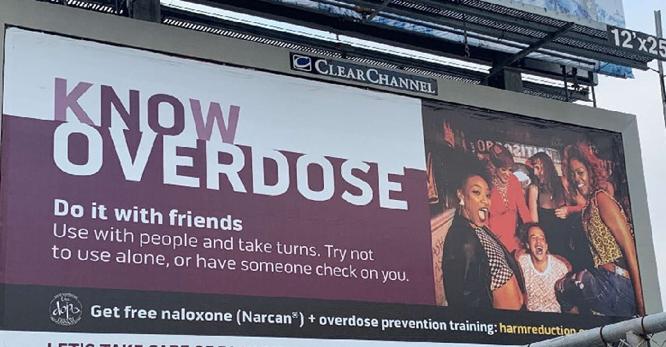

It's a lot of work, and I do this work because it's important to me. What I can't always get behind is how easy some of the stuff we can do in harm reduction makes it for people to kind of coast. The more we destigmatize, the more we run the risk of enabling. I've hit that line so many times I've lost count 'Am I helping this person reduce harm, or am I actually helping them to stay in a harmful situation/pattern for longer'. The answer is complicated.