The Dawn Races of Early Man

ABOUT one million years ago the immediate ancestors of mankind made their appearance by three successive and

sudden mutations stemming from early stock of the lemur type of placental mammal. The dominant factors of these early lemurs were derived from the western or later American group of the evolving life plasm. But before establishing the direct line of human ancestry, this strain was reinforced by contributions from the central life implantation evolved in Africa. The eastern life group contributed little or nothing to the actual production of the human species.

1. The Early Lemur Types

The early lemurs concerned in the ancestry of the human species were not directly related to the pre-existent tribes of gibbons and apes then living in Eurasia and northern Africa, whose progeny have survived to the present time. Neither were they the offspring of the modern type of lemur, though springing from an ancestor common to both but long since extinct.

While these early lemurs evolved in the Western Hemisphere, the establishment of the direct mammalian ancestry of mankind took place in southwestern Asia, in the original area of the central life implantation but on the borders of the eastern regions. Several million years ago the North American type lemurs had migrated westward over the Bering land bridge and had slowly made their way southwestward along the Asiatic coast. These migrating tribes finally reached the salubrious region lying between the then expanded Mediterranean Sea and the elevating mountainous regions of the Indian peninsula. In these lands to the west of India they united with other and favorable strains, thus establishing the ancestry of the human race.

With the passing of time the seacoast of India southwest of the mountains gradually submerged, completely isolating the life of this region. There was no avenue of approach to, or escape from, this Mesopotamian or Persian peninsula except to the north, and that was repeatedly cut off by the southern invasions of the glaciers. And it was in this then almost paradisiacal area, and from the superior descendants of this lemur type of mammal, that there sprang two great groups, the simian tribes of modern times and the present-day human species.

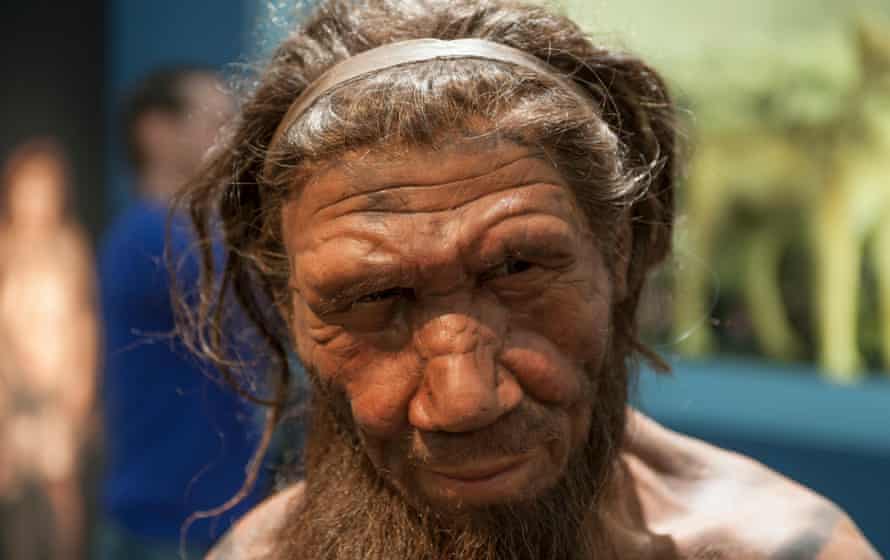

2. The Dawn Mammals

A little more than one million years ago the Mesopotamian dawn mammals, the direct descendants of the North American lemur type of placental mammal,

suddenly appeared. They were active little creatures, almost three feet tall; and while they did not habitually walk on their hind legs, they could easily stand erect. They were hairy and agile and chattered in monkeylike fashion, but unlike the simian tribes, they were flesh eaters. They had a primitive opposable thumb as well as a highly useful grasping big toe. From this point onward the prehuman species successively developed the opposable thumb while they progressively lost the grasping power of the great toe. The later ape tribes retained the grasping big toe but never developed the human type of thumb.

These dawn mammals attained full growth when three or four years of age, having a potential life span, on the average, of about twenty years. As a rule offspring were born singly, although twins were occasional.

The members of this new species had the largest brains for their size of any animal that had theretofore existed on earth. They experienced many of the emotions and shared numerous instincts which later characterized primitive man, being highly curious and exhibiting considerable elation when successful at any undertaking. Food hunger and sex craving were well developed, and a definite sex selection was manifested in a crude form of courtship and choice of mates. They would fight fiercely in defense of their kindred and were quite tender in family associations, possessing a sense of self-abasement bordering on shame and remorse. They were very affectionate and touchingly loyal to their mates, but if circumstances separated them, they would choose new partners.

Being small of stature and having keen minds to realize the dangers of their forest habitat, they developed an extraordinary fear which led to those wise precautionary measures that so enormously contributed to survival, such as their construction of crude shelters in the high treetops which eliminated many of the perils of ground life. The beginning of the fear tendencies of mankind more specifically dates from these days.

These dawn mammals developed more of a tribal spirit than had ever been previously exhibited. They were, indeed, highly gregarious but nevertheless exceedingly pugnacious when in any way disturbed in the ordinary pursuit of their routine life, and they displayed fiery tempers when their anger was fully aroused. Their bellicose natures, however, served a good purpose; superior groups did not hesitate to make war on their inferior neighbors, and thus, by selective survival, the species was progressively improved. They very soon dominated the life of the smaller creatures of this region, and very few of the older noncarnivorous monkeylike tribes survived.

These aggressive little animals multiplied and spread over the Mesopotamian peninsula for more than one thousand years, constantly improving in physical type and general intelligence. And it was just seventy generations after this new tribe had taken origin from the highest type of lemur ancestor that the next epoch-making development occurred—the sudden differentiation of the ancestors of the next vital step in the evolution of human beings on Urantia.

3. The Mid-Mammals

Early in the career of the dawn mammals, in the treetop abode of a superior pair of these agile creatures, twins were born, one male and one female. Compared with their ancestors, they were really handsome little creatures. They had little hair on their bodies, but this was no disability as they lived in a warm and equable climate.

These children grew to be a little over four feet in height. They were in every way larger than their parents, having longer legs and shorter arms. They had almost perfectly opposable thumbs, just about as well adapted for diversified work as the present human thumb. They walked upright, having feet almost as well suited for walking as those of the later human races.

Their brains were inferior to, and smaller than, those of human beings but very superior to, and comparatively much larger than, those of their ancestors. The twins early displayed superior intelligence and were soon recognized as the heads of the whole tribe of dawn mammals, really instituting a primitive form of social organization and a crude economic division of labor. This brother and sister mated and soon enjoyed the society of twenty-one children much like themselves, all more than four feet tall and in every way superior to the ancestral species. This new group formed the nucleus of the mid-mammals.

When the numbers of this new and superior group grew great, war, relentless war, broke out; and when the terrible struggle was over, not a single individual of the pre-existent and ancestral race of dawn mammals remained alive. The less numerous but more powerful and intelligent offshoot of the species had survived at the expense of their ancestors.

And now, for almost fifteen thousand years (six hundred generations), this creature became the terror of this part of the world. All of the great and vicious animals of former times had perished. The large beasts native to these regions were not carnivorous, and the larger species of the cat family, lions and tigers, had not yet invaded this peculiarly sheltered nook of the earth’s surface. Therefore did these mid-mammals wax valiant and subdue the whole of their corner of creation.

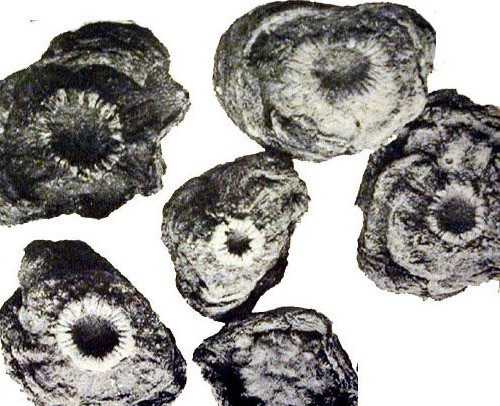

Compared with the ancestral species, the mid-mammals were an improvement in every way. Even their potential life span was longer, being about twenty-five years. A number of rudimentary human traits appeared in this new species. In addition to the innate propensities exhibited by their ancestors, these mid-mammals were capable of showing disgust in certain repulsive situations. They further possessed a well-defined hoarding instinct; they would hide food for subsequent use and were greatly given to the collection of smooth round pebbles and certain types of round stones suitable for defensive and offensive ammunition.

These mid-mammals were the first to exhibit a definite construction propensity, as shown in their rivalry in the building of both treetop homes and their many-tunneled subterranean retreats; they were the first species of mammals ever to provide for safety in both arboreal and underground shelters. They largely forsook the trees as places of abode, living on the ground during the day and sleeping in the treetops at night.

As time passed, the natural increase in numbers eventually resulted in serious food competition and sex rivalry, all of which culminated in a series of internecine battles that nearly destroyed the entire species. These struggles continued until only one group of less than one hundred individuals was left alive. But peace once more prevailed, and this lone surviving tribe built anew its treetop bedrooms and once again resumed a normal and semipeaceful existence.

You can hardly realize by what narrow margins your prehuman ancestors missed extinction from time to time. Had the ancestral frog of all humanity jumped two inches less on a certain occasion, the whole course of evolution would have been markedly changed. The immediate lemurlike mother of the dawn-mammal species escaped death no less than five times by mere hairbreadth margins before she gave birth to the father of the new and higher mammalian order. But the closest call of all was when lightning struck the tree in which the prospective mother of the Primates twins was sleeping. Both of these mid-mammal parents were severely shocked and badly burned; three of their seven children were killed by this bolt from the skies. These evolving animals were almost superstitious. This couple whose treetop home had been struck were really the leaders of the more progressive group of the mid-mammal species; and following their example, more than half the tribe, embracing the more intelligent families, moved about two miles away from this locality and began the construction of new treetop abodes and new ground shelters—their transient retreats in time of sudden danger.

Soon after the completion of their home, this couple, veterans of so many struggles, found themselves the proud parents of twins, the most interesting and important animals ever to have been born into the world up to that time, for they were the first of the new species of Primates constituting the next vital step in prehuman evolution.

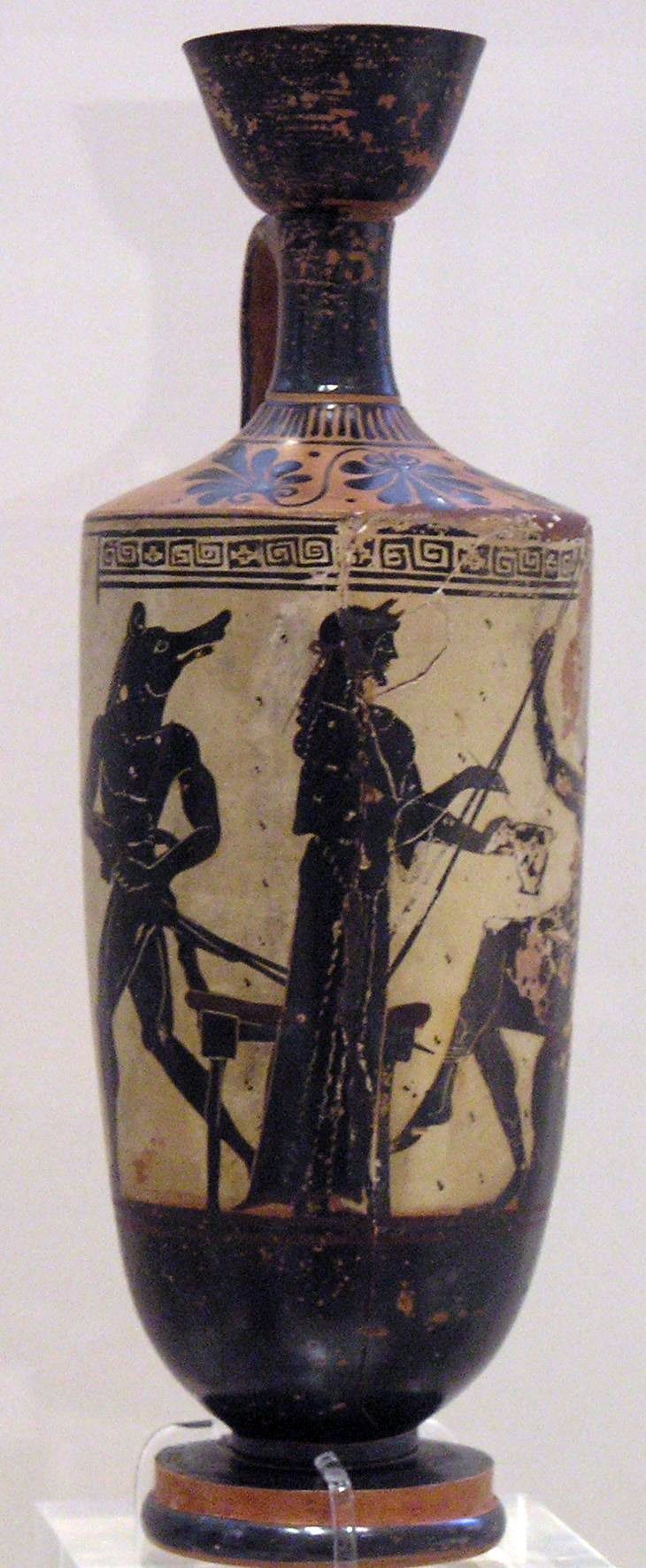

Contemporaneously with the birth of these Primates twins, another couple—a peculiarly retarded male and female of the mid-mammal tribe, a couple that were both mentally and physically inferior—also gave birth to twins. These twins, one male and one female, were indifferent to conquest; they were concerned only with obtaining food and, since they would not eat flesh, soon lost all interest in seeking prey. These retarded twins became the founders of the modern simian tribes. Their descendants sought the warmer southern regions with their mild climates and an abundance of tropical fruits, where they have continued much as of that day except for those branches which mated with the earlier types of gibbons and apes and have greatly deteriorated in consequence.

And so it may be readily seen that man and the ape are related only in that they sprang from the mid-mammals, a tribe in which there occurred the contemporaneous birth and subsequent segregation of two pairs of twins: the inferior pair destined to produce the modern types of monkey, baboon, chimpanzee, and gorilla; the superior pair destined to continue the line of ascent which evolved into man himself.

Modern man and the simians did spring from the same tribe and species but not from the same parents. Man’s ancestors are descended from the superior strains of the selected remnant of this mid-mammal tribe, whereas the modern simians (excepting certain pre-existent types of lemurs, gibbons, apes, and other monkeylike creatures) are the descendants of the most inferior couple of this mid-mammal group, a couple who only survived by hiding themselves in a subterranean food-storage retreat for more than two weeks during the last fierce battle of their tribe, emerging only after the hostilities were well over.

4. The Primates

Going back to the birth of the superior twins, one male and one female, to the two leading members of the mid-mammal tribe: These animal babies were of an unusual order; they had still less hair on their bodies than their parents and, when very young, insisted on walking upright. Their ancestors had always learned to walk on their hind legs, but these Primates twins stood erect from the beginning. They attained a height of over five feet, and their heads grew larger in comparison with others among the tribe. While early learning to communicate with each other by means of signs and sounds, they were never able to make their people understand these new symbols.

When about fourteen years of age, they fled from the tribe, going west to raise their family and establish the new species of

Primates. And these new creatures are very properly denominated Primates since they were the direct and immediate animal ancestors of the human family itself.

Thus it was that the Primates came to occupy a region on the west coast of the Mesopotamian peninsula as it then projected into the southern sea, while the less intelligent and closely related tribes lived around the peninsula point and up the eastern shore line.

The

Primates were more human and less animal than their mid-mammal predecessors. The skeletal proportions of this new species were very similar to those of the primitive human races. The human type of hand and foot had fully developed, and these creatures could walk and even run as well as any of their later-day human descendants. They largely abandoned tree life, though continuing to resort to the treetops as a safety measure at night, for like their earlier ancestors, they were greatly subject to fear. The increased use of their hands did much to develop inherent brain power, but they did not yet possess minds that could really be called human.

Although in emotional nature the Primates differed little from their forebears, they exhibited more of a human trend in all of their propensities. They were, indeed, splendid and superior animals, reaching maturity at about ten years of age and having a natural life span of about forty years. That is, they might have lived that long had they died natural deaths, but in those early days very few animals ever died a natural death; the struggle for existence was altogether too intense.

And now, after almost nine hundred generations of development, covering about twenty-one thousand years from the origin of the dawn mammals, the Primates

suddenly gave birth to two remarkable creatures, the first true human beings.

Thus it was that the dawn mammals, springing from the North American lemur type, gave origin to the mid-mammals, and these mid-mammals in turn produced the superior Primates, who became the immediate ancestors of the primitive human race. The Primates tribes were the last vital link in the evolution of man, but in less than five thousand years not a single individual of these extraordinary tribes was left.

5. The First Human Beings

From the year A.D. 1934 back to the birth of the first two human beings is just 993,419 years.

These two remarkable creatures were true human beings. They possessed perfect human thumbs, as had many of their ancestors, while they had just as perfect feet as the present-day human races. They were walkers and runners, not climbers; the grasping function of the big toe was absent, completely absent. When danger drove them to the treetops, they climbed just like the humans of today would. They would climb up the trunk of a tree like a bear and not as would a chimpanzee or a gorilla, swinging up by the branches.

These first human beings (and their descendants) reached full maturity at twelve years of age and possessed a potential life span of about seventy-five years.

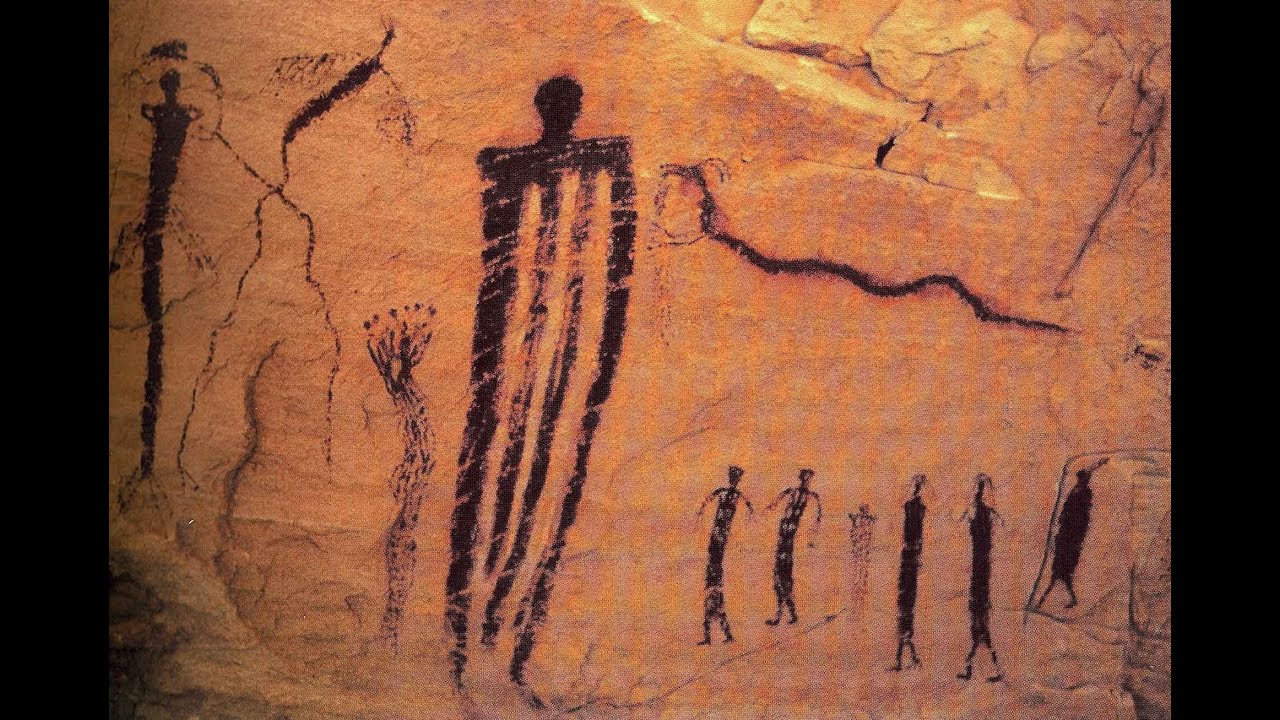

Many new emotions early appeared in these human twins. They experienced admiration for both objects and other beings and exhibited considerable vanity. But the most remarkable advance in emotional development was the

sudden appearance of a new group of really human feelings, the worshipful group, embracing awe, reverence, humility, and even a primitive form of gratitude. Fear, joined with ignorance of natural phenomena, is about to give birth to primitive religion.

Not only were such human feelings manifested in these primitive humans, but many more highly evolved sentiments were also present in rudimentary form. They were mildly cognizant of pity, shame, and reproach and were acutely conscious of love, hate, and revenge, being also susceptible to marked feelings of jealousy.

These first two humans—the twins—were a great trial to their Primates parents. They were so curious and adventurous that they nearly lost their lives on numerous occasions before they were eight years old. As it was, they were rather well scarred up by the time they were twelve.

Very early they learned to engage in verbal communication; by the age of ten they had worked out an improved sign and word language of almost half a hundred ideas and had greatly improved and expanded the crude communicative technique of their ancestors. But try as hard as they might, they were able to teach only a few of their new signs and symbols to their parents.

When about nine years of age, they journeyed off down the river one bright day and held a momentous conference. Every celestial intelligence stationed on Urantia, including myself, was present as an observer of the transactions of this noontide tryst. On this eventful day they arrived at an understanding to live with and for each other, and this was the first of a series of such agreements which finally culminated in the decision to flee from their inferior animal associates and to journey northward, little knowing that they were thus to found the human race.

While we were all greatly concerned with what these two little savages were planning, we were powerless to control the working of their minds; we did not—could not—arbitrarily influence their decisions. But within the permissible limits of planetary function, we, the Life Carriers, together with our associates, all conspired to lead the human twins northward and far from their hairy and partially tree-dwelling people. And so, by reason of their own intelligent choice, the twins did migrate, and because of our supervision they migrated northward to a secluded region where they escaped the possibility of biologic degradation through admixture with their inferior relatives of the Primates tribes.

Shortly before their departure from the home forests they lost their mother in a gibbon raid. While she did not possess their intelligence, she did have a worthy mammalian affection of a high order for her offspring, and she fearlessly gave her life in the attempt to save the wonderful pair. Nor was her sacrifice in vain, for she held off the enemy until the father arrived with reinforcements and put the invaders to rout.

Soon after this young couple forsook their associates to found the human race, their Primates father became disconsolate—he was heartbroken. He refused to eat, even when food was brought to him by his other children. His brilliant offspring having been lost, life did not seem worth living among his ordinary fellows; so he wandered off into the forest, was set upon by hostile gibbons and beaten to death.

6. Evolution of the Human Mind

We, the Life Carriers on Urantia, had passed through the long vigil of watchful waiting since the day we first planted the life plasm in the planetary waters, and naturally the appearance of the first really intelligent and volitional beings brought to us great joy and supreme satisfaction.

We had been watching the twins develop mentally through our observation of the functioning of the seven adjutant mind-spirits assigned to Urantia at the time of our arrival on the planet. Throughout the long evolutionary development of planetary life, these tireless mind ministers had ever registered their increasing ability to contact with the successively expanding brain capacities of the progressively superior animal creatures.

At first only the spirit of intuition could function in the instinctive and reflex behavior of the primordial animal life. With the differentiation of higher types, the spirit of understanding was able to endow such creatures with the gift of spontaneous association of ideas. Later on we observed the spirit of courage in operation; evolving animals really developed a crude form of protective self-consciousness. Subsequent to the appearance of the mammalian groups, we beheld the spirit of knowledge manifesting itself in increased measure. And the evolution of the higher mammals brought the function of the spirit of counsel, with the resulting growth of the herd instinct and the beginnings of primitive social development.

Increasingly, on down through the dawn mammals, the mid-mammals, and the Primates, we had observed the augmented service of the first five adjutants. But never had the remaining two, the highest mind ministers, been able to function in the Urantia type of evolutionary mind.

Imagine our joy one day—the twins were about ten years old—when the spirit of worship made its first contact with the mind of the female twin and shortly thereafter with the male. We knew that something closely akin to human mind was approaching culmination; and when, about a year later, they finally resolved, as a result of meditative thought and purposeful decision, to flee from home and journey north, then did the spirit of wisdom begin to function on Urantia and in these two now recognized human minds.

There was an immediate and new order of mobilization of the seven adjutant mind-spirits. We were alive with expectation; we realized that the long-waited-for hour was approaching; we knew we were upon the threshold of the realization of our protracted effort—to evolve will creatures on Urantia.

The Urantia Book Paper 62 The Dawn Races of Early Man 62:0.1 (703.1) ABOUT one million years ago the immediate ancestors of mankind made their appearance by three successive and sudden mutations stemming from early stock of the lemur type of placental mammal.

www.urantia.org