mr peabody

Bluelight Crew

- Joined

- Aug 31, 2016

- Messages

- 5,714

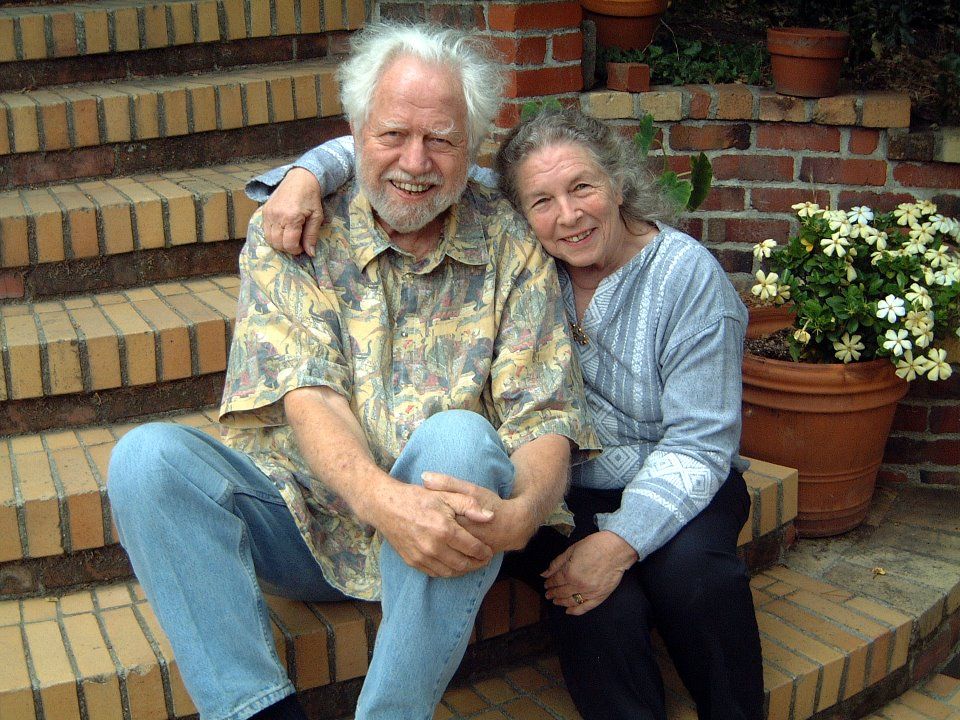

Chemophilia – An Interview with Ann and Alexander Shulgin

Berkeley, California, 1993

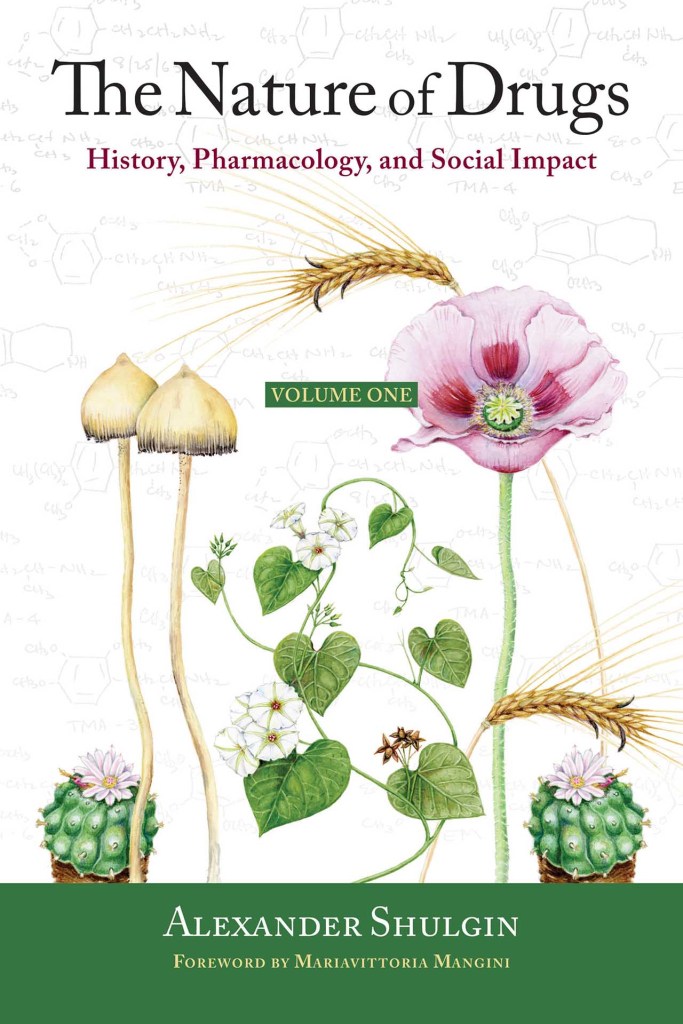

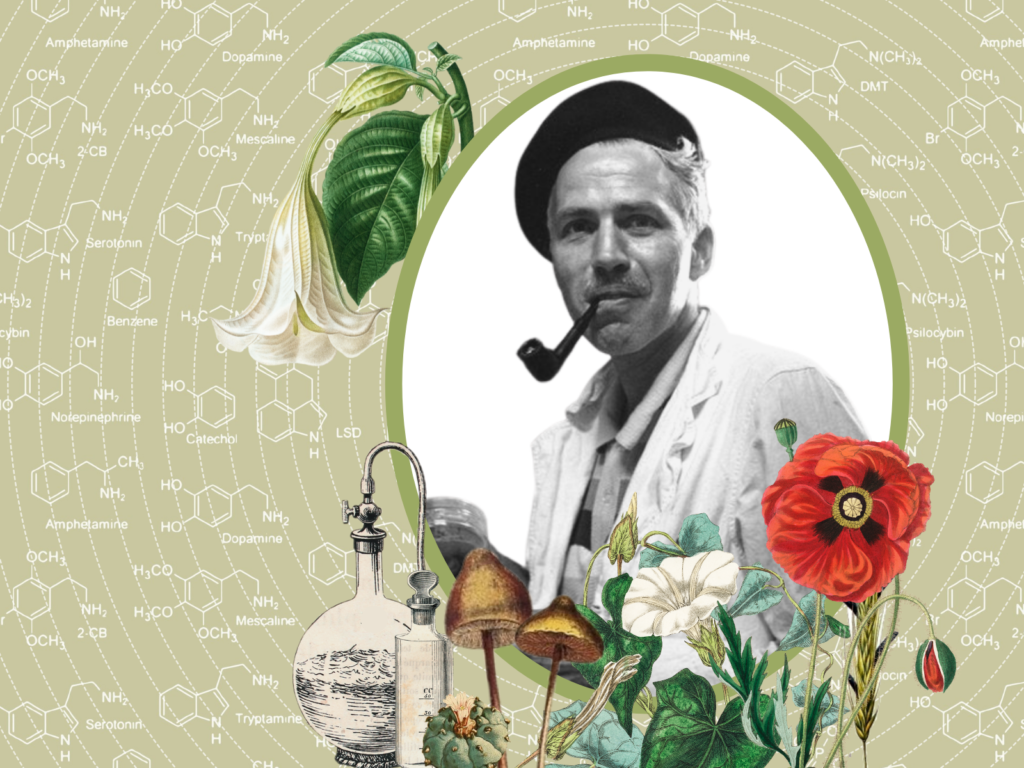

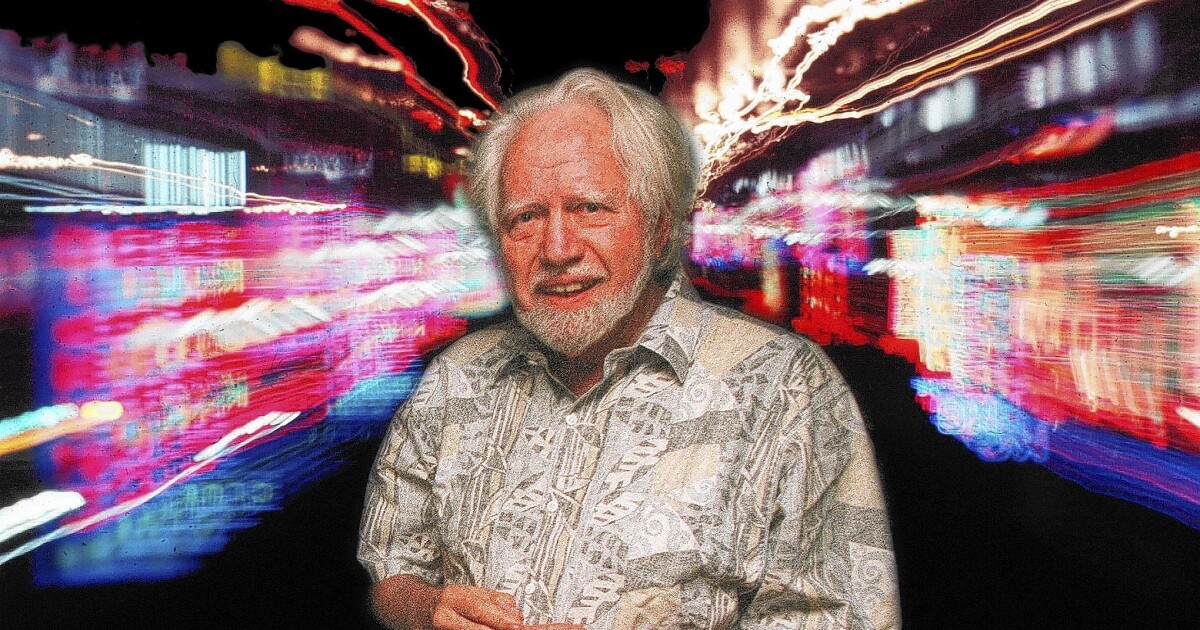

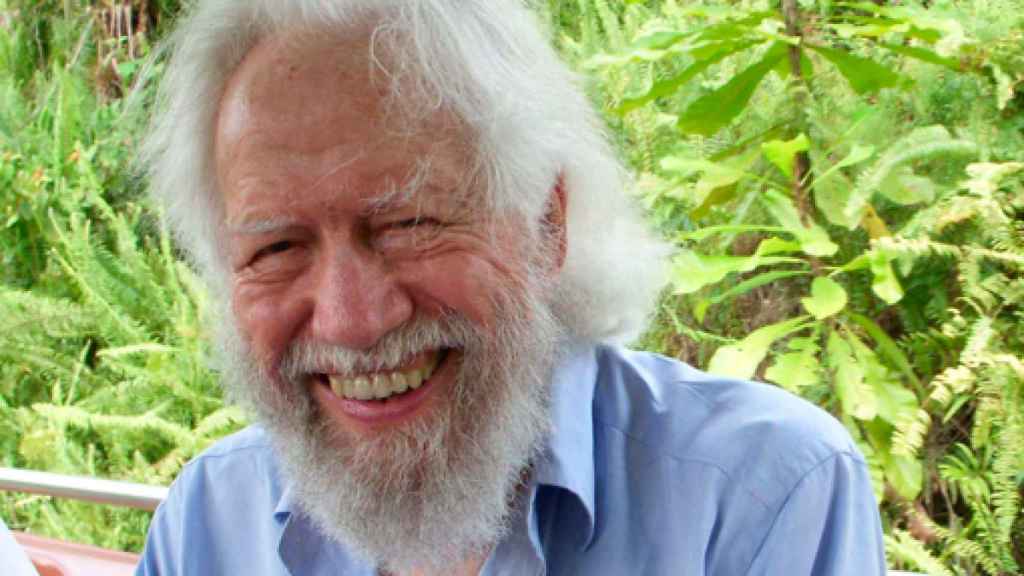

Alexander (Sasha) and Ann Shulgin were on the frontier of designer neurochemistry, developing a plethora of miraculous pharmacological keys that unlock different aspects of the brain is hidden potential. They are known to many as the authors of the underground best-seller PIHKAL: A Chemical Love Story, the title of which is an acronym for Phenethylamines I Have Known and Loved. Alexander was a long-standing, well-respected research chemist and professor of pharmacology at the University of California at Berkeley, where he earned his doctorate in biochemistry in 1954. He authored 150 scientific research papers, twenty patents, and three books. Although Alexander was quite outspoken regarding his opposition to the so-called war on drugs, he was a scientific consultant for such state-run organizations as the National Institute on Drug Abuse, NASA, Lawrence Radiation Laboratory, and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA).

In private, in his government-licensed research lab, Alexander spent the last thirty years of his life discreetly yet legally designing hundreds of new psychoactive compounds, particularly psychedelics. Along with his wife, Ann, and a small, brave, and dedicated research group, they sampled each new drug as it is developed. Through the cautious escalation of dosage, they discovered and mapped out the range of each new drugs effects, experimenting with the various aspects of their psychological and spiritual potential. Most of Alexanders psychoactive designer molecules are unknown to the public, but a few, such as 2CB (an MDMA analogue) and DOM (better known as STP), have received widespread distribution. Their research continued until Sasha's death in 2014. Their book, PIHKAL, details their truly remarkable adventures and, for those with a solid background in chemistry, and provides the esoteric recipes for recreating hundreds of Alexanders finely crafted magic molecules.

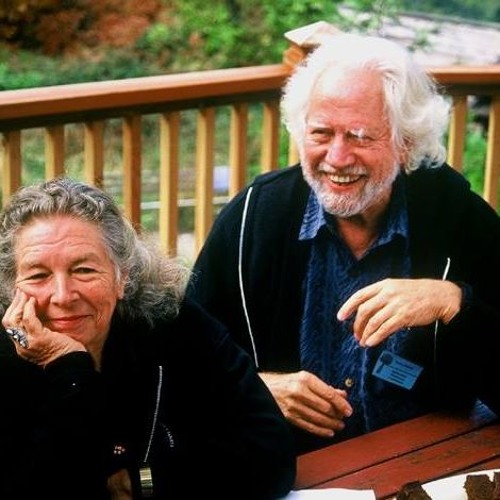

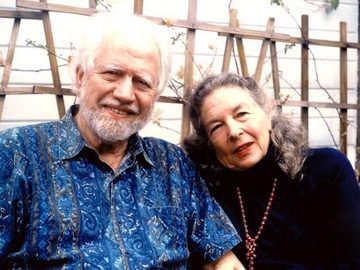

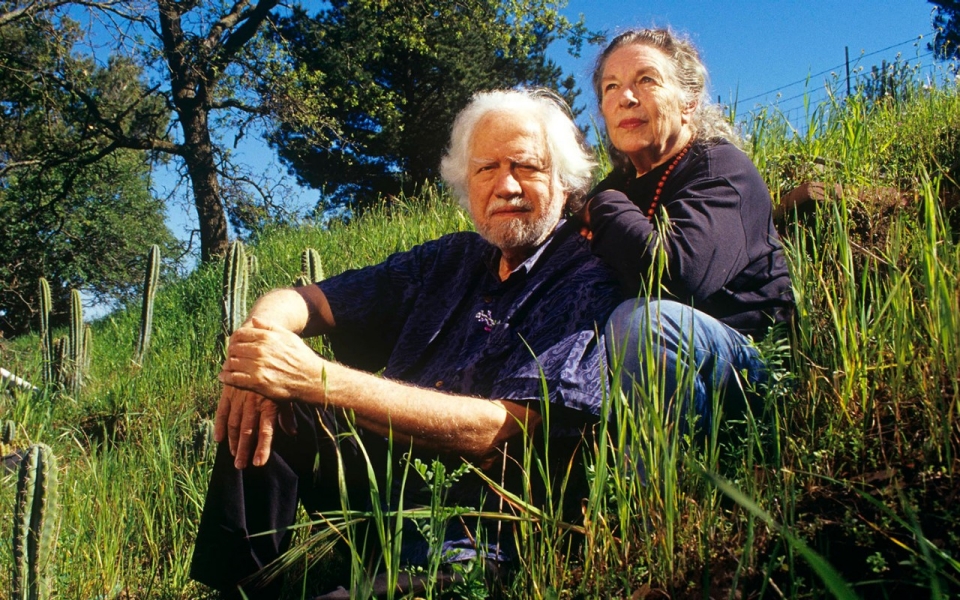

Alexander and Ann made a very compatible research team: they complemented one another; and their relationship reflects a deep commitment to inner exploration. They were extremely warm, and anxious to share what they had learned through their experimentation. We interviewed them at their home in Lafayette east of Berkeley in northern California in 1993. Ann was strong, solid and grounded, very much connected to the earth. Before moving to northern California as a teenager she had lived in four countries. She worked as a medical secretary at the UCSF Medical Center. She was also a psychotherapist.

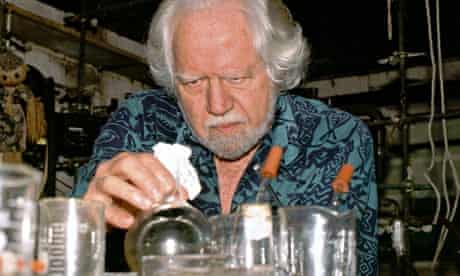

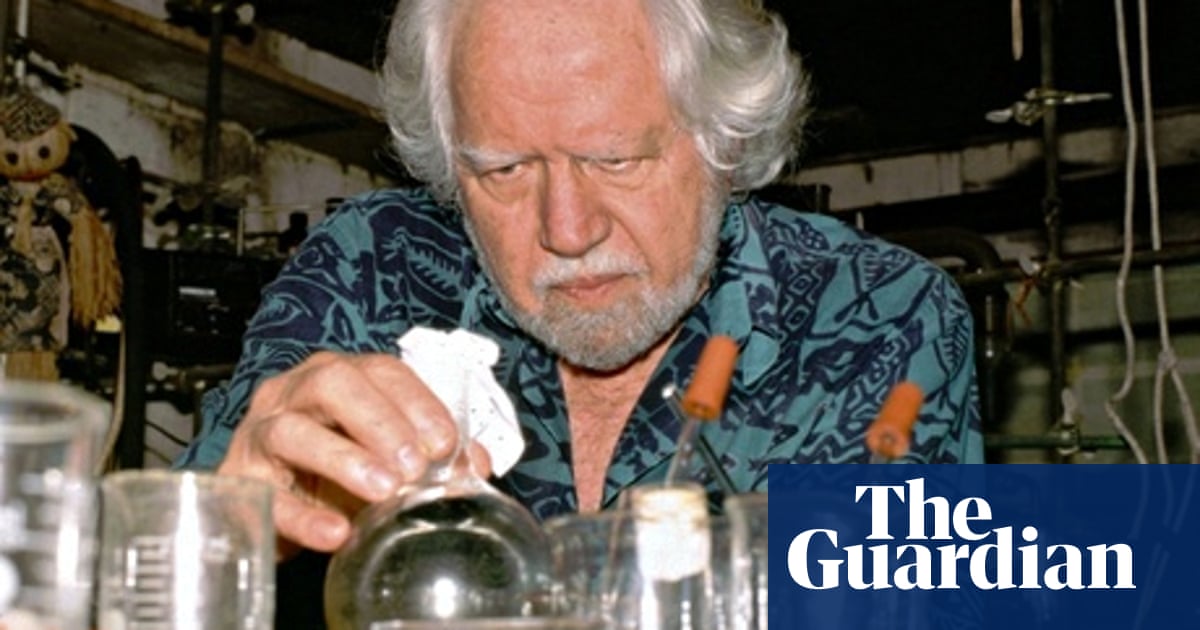

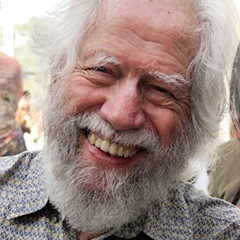

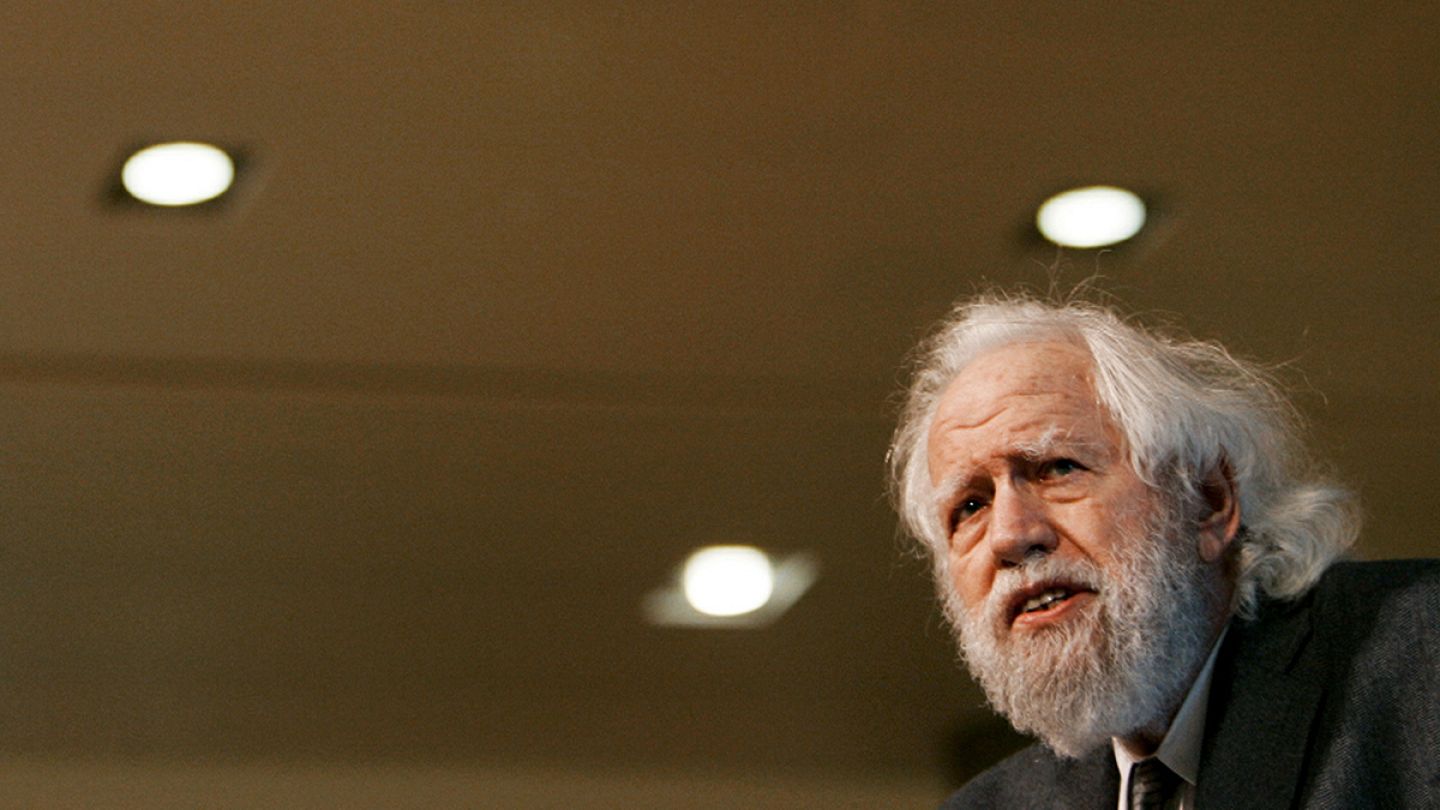

A wild electrical current seems to buzz through Alexanders nervous system, as evidenced by the white hair that seems to stand on end on his head and face, and the excited manner in which he explained everything. Alexanders research laboratory, just a short walk from the main house, was filled by a complex of interlocking flasks, glass beakers, plastic tubes, heating coils, and countless bottles; it looked dramatic enough to be used as a Hollywood movie set. The only chemicals that we sampled, however, were in the cheese sandwiches that we had for lunch before we began the interview. Even so, we do feel ourselves to be in an altered state.

DJB

David: What was it that inspired you to write Pihkal?

Alexander: I was inspired partly by the history of Wilhelm Reich. I discovered that in his very last years he got into very unusual and not totally acceptable areas of hypotheses, such as making rains fall by means of electro-static guns and other such ventures.

The FDA filed a lawsuit against him for promoting radical equipment that had not been approved by them. They put him in jail and he died there. After his death the FDA took all his lab books and papers and burned them. One of the reasons I wrote Pihkal was because I could see the need to get a lot of information that had not been published into a form that just could not be destroyed.

Ann: And I couldn't imagine him writing all that fun stuff without my help. (laughter) I co-authored one paper with him before and discovered that its a great ego-boost to do good writing; I never had anything published before. It became the most exciting thing in the world to do, especially because it was pushing against the establishment.

My model and my hero was Castaneda, but what I wanted to do was bring in the personal which he failed to do, marriage, kids, love, soup, every day reality. Our feeling about psychedelics is that if you use them in the right way, they enrich your everyday life. You learn to think a different way about the ordinary things you see.

Rebecca: What is a phenethylamine, why is it so special and what role has it played in your research?

Alexander: There are a collection of neurotransmitters in the brain and two of the largest families are the phenethylamines and the tryptamines. And it turned out that all the known psychedelics around the time I got curious in this area, back in the 50s and 60s, were either phenethylamines or tryptamines. It has now been shown that this is a very good guide. Nature said, here are the two basic building blocks, and if you are going to do something with the brain, it is going to be with one or the other.

David: Why did the two of you use ficitonal names in the book when the story was obviously autobiographical?

Ann: Among the drugs we were writing about some, like LSD, are illegal. It was risky enough writing the book in the first place. We didn't know what to expect from the establishment, if anything. Some people late at night with baseball bats smashing up the lab was a perfectly reasonable possibility. Using fictional names gave us a deniability.

The second reason was so that I could tell my children that the sex in the book wasn't actually us. (laughter)

Also, we didn't want to jeopardize our next book. At this point, not only has there been no fire from heaven descending on our heads, and the DEA itself one of our best customers, it is easy to look back and ask why were we worried.

Alexander: One of the things I did was to send a score copy of the book to people within the DEA with covering phrases like, Here is a book that will provide you with a lot of information which may be useful to you.

David: What was their response to it?

Ann: They loved it. One of the higher administrators of the DEA in Washington said, My wife and I read your book and its great!

David: Sasha, how did you become a chemist?

Alexander: My doctorate is in biochemistry, but I found that it didn't have the magic and the music of chemistry. In my teaching class at Berkeley I would ask, How many people are taking organic chemistry? And you'd hear this groan. Why? Because the typical instruction would be, Go and read pages 83-117 in the textbook, and we will have a quiz on Monday. People hated it! Chemistry, however, is an art, its music, it is a style of thinking. Orbitals are for mathematicians, chemistry is for people who like to cook!

Some of my colleagues would often have a goal and if something went wrong they'd try and find out how else they could get it to go right. My argument has always been, if something went wrong, "Oh wow! Out of this will come something unexpected." That led me into a very great curiosity about the mind process, which was greatly amplified by my first mescaline experience.

Drugs do not do things, they are allowing you to do things. It is not an imposition from the outside. People tend to say, What did that drug do? or, How did the drug do what it did? or, I took a drug and it did such and such. In each instance, this is giving up your power to an inert white solid. The drug catalyzes and facilitates but it doesn't do things. That puts it in perspective. You don't have to give credit to a drug.

David: And it also encourages the person to take responsibility.

Alexander: Completely. You cant live without that.

Rebecca: Do you ever find yourself making a judgment that what you are experiencing is a quality of the drug rather than something inherent in your own psyche?

Alexander: If I do then that experience is sure to be a bummer! (laughter)

Look at yourself in the mirror, it is a good catharsis. Its me and the drug. Its a relationship which is available to everyone. Everybody has the possibility of going into some sort of ecstatic experience, at any time, without drugs, even at the grocery store. Now there's a thought! (laughter)

Ann: If this were a property of the drug, it would be the equivalent of the atom bomb! It is very useful for us that Sasha's metabolism is just about as different from mine as it could possibly be. I had a crisis week which was brought about by 40mg of something which turned out later to be absolutely inactive. That is the placebo effect, which can happen on any drug. But he has often taken a drug which he seems to have a perfectly okay time on at an active level, and I will take it and have a terrible time!

Rebecca: But haven't you found that these drugs do have a certain character to them, a tendency to bring out a particular aspect of the psyche?

Ann: The drug has a physical effect if nothing else, and how my own individual chemistry and metabolism uses that drug might be quite different than the way somebody else does it.

David: Do you think that the states of consciousness you produce with your molecules could be produced by the endogenous neurotransmitters in the brain, or are you producing states of consciousness that are unique and have never been and could never have been produced before without the drug?

Alexander: I think they are deeply embedded in the human animal.

Ann: (to David) I have a compulsion. Its a mother thing. Could you put your left foot up please? (She ties his shoelace...)

Alexander: I was asked almost the same question a few years ago, so I made up a chart about telephones. The finger dial system phone can be seen as an analog of the brain. All you're doing, if you dial the number one and release it, is making one very fast break in the integrity of the system. If you dial the six and release it, it makes six breaks in the system. Then the relay gets broken three times when you dial three, two times when you dial two and then five times, and you have the number 6325. You see, you make the circuit by the number of times you break the relay. In fact, if you are very fast with your two fingers you can dial 911 by hitting the cradle, which gives you the dial tone 9 times very fast and then once and then once again.

Then you have the push button system. Every time you hit a button you are actually activating two frequencies simultaneously. They devised frequencies so that there is no harmonic interference which could give you a false signal. You are not imposing breaks in the system, you are super-imposing two non-conflicting frequencies in the system.

I look upon this as the true analog of the human brain. The numbers represent serotonin, dopamine etc. If you want a signal to come through, you get this neurotransmitter combination which combines with this and that, and the next thing you know you have a thought process and memory.

But when they designed the system, they didn't make it three by four, they made it four by four. These extra four stops have the rather unimaginative names of A, B, C and D and to operate them there is a very secret frequency of 1633 cycles per second. So if you play around with these, you get into areas you wouldn't believe! The military and deep computer language use these four additional stops. But they are not visible on your telephone.

And of course, these stops represent your psychedelic drug neurotransmitter which also gets you into weird places. All the wiring is there but you don't have access to it because 2 million years ago it got bred out of us because it didn't have survival value, in spite of what Terence McKenna says. So the wiring of the brain can use a psychedelic, but the transmitter that makes it a functional network is not available.

David: How did you first start designing drugs, and from where do the two of you draw this courage to take unknown substances into your body?

Alexander: It doesn't take that much courage. You're not foolish. You don't take a whole teaspoonful to see if you burp. (laughter) You start out with a reasonable estimate of what you think might be an effective level, and you divide that by whatever number your wisdom and judgment tells you.

David: Nonetheless, you are still venturing off into the unknown.

Alexander: Admittedly, the first time is an unknown, but you start with a level where it would be hard to believe it would have an effect. Almost never are you surprised, and when you are surprised you learn from it.

Ann: What takes real courage is being on the street or at a Rave and somebody gives you a little packet of something, and it doesn't say what it is or how much it is.

David: Well some people would call that stupidity rather than courage.

Alexander: People call what I do stupid too. (laughter) But I know what I have; I know its purity, and I know I can take it a second time.

Rebecca: You also have a number system which helps you to measure your reaction to a drug. It certainly beats having to come up with a barrel load of adjectives to describe what is happening.

Ann: Yes, and its helpful to the research group also. Everybody knows when its not just a plus 2. Perhaps it is a plus 2.65. (laughter)

Alexander: It does have the value of being able to be applied, not only to psychedelic drugs, but to anything from stimulants to sedatives. At the first level you are aware of something going on but you are not aware of how long it goes on. At the next level you are aware how long it goes on, but you can't give a name to what is happening. At the third level, whether or not you know how long it goes on or can give a name to whats happening, you don't choose to go out and do anything else because you are not totally in command of your physical and mental capacities. Each of these levels are different degrees of acceptance of the drugs action.

Rebecca: What therapeutic value have you found for the drug MDMA, and why was it made illegal?

Ann: I worked for two years as a co-therapist with a highly trained hypnotherapist before MDMA was made illegal, but psychotherapy with any kind of psychoactive drug was still not generally accepted in the medical community. The many therapists who were using it did not publish because it was not widely known and accepted by their peers.

One of the reasons that MDMA was made Schedule I so quickly was that the DEA found it in a lab which was making something else illegal, and decided to sweep it in with the rest of the stuff. They knew nothing about it.

Alexander: One of the rationalizations for it having been made scheduled was that a group in Chicago were studying the effects of MDA and had found some serotonin neuron changes in experimental animals. A member of this group was on Donahue and spoke about this. Immediately they said, "Well, if that happens to MDA, MDMA has almost the same name, it is almost the same compound, maybe it would also be a negative." In the report that came out it was stated that there are a lot of similarities between the two drugs, and that was one of the rationales for immediate emergency scheduling.

David: But there actually is some evidence that MDMA causes degeneration of the dendrites.

Alexander: Yes. It is temporary. The consequence of that is not understood. It is also species-specific: monkeys do, rats do, dogs don't, mice don't and the effects in humans are unknown.

David: So it is questionable as to how accurate the spinal tap studies were which showed that there was less serotonin...

Alexander: The results are ambiguous. There were two basic studies. One of them found no measurable changes. All of these were people who were alleged to have used the drug recently, but they did not make the very necessary check to see if the drug was in the person. If not in the person, you may be looking at long-term residues of something which may not be MDMA. The other study showed no significant difference but it was suggestive. (laughter)

Rebecca: Describe to us some of the applications of MDMA.

Ann: The most valuable effect of MDMA is that it enables insight. The patient or the client may regard the possibility of having insight into himself as a very threatening thing. One of the problems that most human beings suffer from is the suspicion that the core essence of who they are deep down is a monster. There is this terrible fear that when you get down to it, the essential you is going to be discovered to be a rotten little slime-bag. (A bit strange, if you ask me. -ed)

MDMA, in some way we don't yet understand, removes that fear. It allows you not only to take a really deep look at who you are but to show you that you are a combination of angels and demons, and that theyre all valid. Apart from the removal of the fear, there is also a kind of good-humored acceptance that this drug allows you to feel. There is a validation of the self which is a miraculous and marvelous thing to experience. MDMA does not remove common sense caution, you still don't cross the road at the red light, but this deep-seated fear is gone.

It is also an extraordinary tool for discovering repressed memories. When I was doing therapy, a great many of our patients were women who were professionals in the child-abuse field. An extraordinary number of them had gone into the field not knowing that they themselves had been sexually abused as children. MDMA brought out these memories. It is a tremendous uncoverer, but with the uncovering is a gentle, compassionate validation and acceptance.

We also worked with married couples. What it seems to do with two people who are having problems is, it allows them to forget the defensiveness of, "you said that first, no I didn't," kind of thing. They can drop all that, and get hold of the feelings of love again.

One of the most moving things that happened was when Sasha and I gave MDMA to one couple who ended up holding hands again and being able to reaffirm the commitment they had. Two weeks later their older son was diagnosed with leukimia. He died four years ago. They said that if they hadn't had that day with MDMA, they didn't know if they could have supported each other through what was an extremely difficult time. One of the things I want to do in our next book, Tihkal, is to write about psychotherapy with psychedelics.

After MDMA was made illegal, all the therapists who had been using it told us they would never quit. Of course, the entire method of using it would change. They would have to know the patient for at least a year in ordinary therapy before they even mentioned it. The patient would also have to be able to deal with the fact that they would be committing a felony. Ive used the phrase that MDMA is penicillin for the soul, because that is exactly the way therapists feel about it. It is already used legally in therapeutic settings in Switzerland.

Rebecca: MDMA seems to work very differently to traditional therapeutic drugs. Thorazine is designed to suppress what is happening to the patient whereas MDMA opens it all up.

Ann: It also requires a different kind of training of the therapist. Handling one particular persons psyche for six hours is very different from fifty minutes.

Rebecca: PCP has a bad reputation because many people have become extremely violent while under its influence. Is there a drug, do you think, which could turn the Dalai Lama into a raving sociopath?

Alexander: In my case PCP didn't release any aggressive tendencies at all.

Rebecca: Why does it have this reputation then? Isn't it perhaps more likely to cause aggression than, say, marijuana?

Alexander: PCP, like Ketamine, is an anesthetic, people don't get feedback of pain. They don't know that they are exceeding their normal capacities of muscle. So the anesthetic aspects of it could allow violent behavior simply because the person may not be able to feel the consequences of their violence.

David: I spent years working in psychiatric hospitals and when somebody came in with a psychotic episode triggered by LSD (which was very rare) it was far less extreme than one triggered by PCP.

Alexander: It is an entirely different action on the nervous system. Most of the psychedelics as with most of the stimulants are usually considered sympathomimetics, they imitate the sympathetic side of the nervous system. PCP, Ketamine and Datura are parasympatholytics. Instead of actively participating in encouraging one side of the nervous system, they fail to discourage the other side of the nervous system when these two sides are in balance. Things shift in a direction either because you are pulling a certain way or else because you are releasing the restraints that keep you from going that way.

The analogy I give is in the dilation of the eye. The pupil of the eye is dilated because of two opposite things. One, you have things that are pulling it open and you have sphincter muscles that try to keep it closed. So, if you give a stimulant or a psychedelic, that activates the puller-opener mechanism and the eye dilates. The sphincter muscles are okay, they are just over-powered. If you force a light in that persons eye, you get a reflexive closing down of the pupil, and then it will open up again.

Now if you give something that craps up the sphincter muscles, like Ketamine, the eye dilates because the radials are pulling it open, and the sphincters don't have any power to keep it from happening. If you flash a light in that persons eye, it doesn't close because the mechanism that closes it doesn't work.

Rebecca: Why is it that the parasympatholytics: Datura, Belladonna, PCP and Ketamine, have this reputation for being the somewhat darker and weirder members of the psychedelic family.

Alexander: You have amnesia for what?s going on in there. There is a dream-like quality. You have an idea of what is happening but the detail is elusive.

Ann: I have never experienced what could be called an hallucination. The word hallucinogen is one we really don't like. (I very much agree with this. -ed)

Alexander: I have talked to people to whom that has happened. But the same thing can be said of finding Christ at a revival meeting. Suddenly there it was!

Ann: I have a prejudice against anything that causes amnesia. What is the point? If you can't remember, you can't learn anything!

Alexander: There was a person who was giving his impressions while on Ketamine. Just before he stopped talking entirely he said, I think I see it, I think I finally have it, in fact I know I have it, it is completely clear, its obvious? This went on for hours, and it turned out that it was the sole of someones shoe!

Ann: I like your question; is there a drug which could turn the Dalai Lama into a sociopath? I suspect that the Dalai Lama has developed his own consciousness sufficiently that he is already acquainted with this animal. So he's already made his choices. During psychedelic therapy, you eventually have to go to the monster and get to know it. The Jungians go as far as getting a good look at it and accepting that it is there. What we do is, we go into it and look out of its eyes so that we become it.

The worst terror I think a human being can experience is when he or she is facing doing that, because we are all afraid that we are going to get stuck in the demon. What you have to realize is that you have already made your choices of what side you're going to be on in this life. You have basically chosen whether you're going to be a nurturing person rather than a destroyer and soon.

Once you get inside the demon, the first thing you experience is the absolute lack of fear and then you begin to recognize that this is also the survivor aspect of yourself. There is a part that takes care of you. Then it begins to transform, and you recognize its quality of total selfishness, it is going to take care of you and nobody else, right? But it is your ally. And then you begin to recognize its positive aspects.

David: That is interesting, because part of the therapeutic process for people with multiple personality disorder involves an understanding that each personality has a particular function.

Ann: Absolutely. This is why I believe that all psychedelic use, even if its at a Rave, is part of a spiritual search. My suspicion is that psychedelics are going to be accepted, if they ever are, only when they are seen as tools for spiritual development. But the trouble is that the West basically treats the unconscious as the enemy, as if only an ax-murder will be found in there! For Gods sake, repress it! (laughter)

David: Because drug use can present serious problems, every society needs a well thought out drug policy. The American government's personification of drug users through the criminal justice system has, in the face of rational thinking, been a totally unsuccessful attempt at fighting drug abuse and has seriously eroded many of our constitutional rights. What do you see as the cause behind this zealously fought War on Drugs and what kind of drug policy do you envision for a tolerant society of the future?

Alexander: Well two changes I see as indispensable. One is the laws will have to change and that is going to require the other part which is honest education and distribution of information about drugs and their actions. The way the term abuse is used nowadays is that it means any use of a drug which you don't approve of.

David: For a long time I thought all drugs should be legal and available to everybody until I read Mark Kleiman's book Against Excess. The cost of drug abuse to the taxpayer is a point he brings up.

Alexander: Well if someone has a drug abuse problem and he requires medical treatment, is that worse than having a drug abuse problem and being in prison, which also puts as strain on the tax-system? One of the reasons you can't rationally pin-point harm reduction is because you cannot measure harm. What is the harm of a person using a drug which is not approved of by society? To one person, trivial, to another person who's son has just died from an over-dose, immense.

So you cant put a quantitative value on harm. Also, if you want to reduce harm (and this is the argument for the Drug War), you cant put a number on the reduction. Lastly, the thing you do to reduce harm, itself does harm. If you remove drug laws you have ten thousand unemployed law-enforcement people, and they are going to see that in an entirely different light. On the other hand, they passed a law in Florida that if you are on welfare and you go into prenatal care and test positive for illegal drugs in your urine, you may suffer the confiscation of your child. A woman, instead of facing the possible loss of her child, just won't go in for the prenatal exam. What is the harm? You can't calculate it.

What would be the damage to society from changing the drug laws? If you look at it through one lens you can see that it is going to be horrendous, and if you look through another lens you can see that it is going to be a lifesaver.

Rebecca: I was in a hardware store and there was this big sign up which read, We ensure that our employees are tested for drugs. A strong 1984 feeling came over me. What do you think about urine tests?

Alexander: It is intolerable! There is no basis for a urine test unless there's a reason to believe that a person is incompetent in some way.

David: Even then you should measure their performance, not her urine.

Alexander: Exactly. If you run a bus into a group of pedestrians, and you stagger off the bus and go into the nearest bar for a drink, there may possibly be reason for a urine test. If a person is going to fly an airplane, and before he boards the plane you take a sample of his urine and send it off to Florida for analysis, it doesn't protect the people on that flight at all!

You have no protection even today for the presumption of innocence. That does not exist in the constitution. Taking of a urine sample is a presumption of guilt.

Rebecca: The drug laws haven't changed anything in the constitution, so why are we all getting this nasty feeling that our constitutional rights are being eaten away?

Alexander: Its how they are being interpreted. The perversion of the laws which were written with good intent but which have been allowed to be eroded is something which the constitution can?t even touch. I can show you the original writings of the social security law which says that your social security number should remain private.

The original laws of income tax documents say that your submission of an income tax form to the federal government shall be a private correspondence. Needless to say, that has been scrapped. You now have to get a fingerprint to obtain a drivers license, but California State Law states that a fingerprint serves one function only, to identify a person in the conjunction with a criminal charge. The measures which they can go to is frightening.

Rebecca: You talked in Pihkal about how racism has been one of the root causes of prejudice against various drugs.

Alexander: Right. The connection between racism and drugs started in the public consciousness with the building of the Trans-Continental Railway. To save on labor costs we hired Chinese immigrants and they brought with them the practice of opium-use. More and more regulations were put into place to limit and control access to opium which was soon considered a social evil. The marijuana laws were put into effect to control Mexicans coming over the border, and cocaine is nowadays very much associated with blacks in the inner cities.

Rebecca: What benefits have you both received from taking psychedelic substances?

Alexander: I think I have learned about myself a little more thoroughly from the inside out and I have learned to take myself a little less seriously. I have also learned not to take anything I hear as gospel, even if I say it myself! (laughter)

Ann: Psychedelics have allowed me not only to explore myself and my own levels of consciousness to an extraordinary extent, but by doing so I feel that I am beginning to understand what the human consciousness is. I also have a compulsion to understand what the universal consciousness is, lets aim as high as we can! (laughter) The exploration is never dull.

There are so many kinds of knowing, and the kinds of knowing that have the most impact are unexplainable. But I like to try to put into words the incomprehensible things that I find. These same experiences are in everybody's psyche, so if I find the right words I may be able to elicit some sort of response from the unconscious of the reader, and perhaps encourage people to be less afraid of understanding themselves.

Rebecca: What would you say to someone who suggested that drug use was simply a form of escapism?

Ann: It is amazing to me that people use the term escape in association with psychedelics. I have found them to be the most incredibly hard work, and Ive never escaped with any psychedelic experience.

Alexander: The same thing could be said about going to a symphony orchestra and listening to concerts or going to church. These could also be looked upon as escape.

Ann: The fact that we use the word escape that way, implies that everybody in this culture regards what they call reality as a grim and miserable thing.

Alexander: Eu as a prefix means normal. Euthyroid means you have a normal thyroid function. The word euphoria means that this is the way you should feel. If you don't feel the way you should feel, that would be dysphoric.

Ann: This culture regards a state of euphoria as something abnormal!

Rebecca: Have either of you had to face the problem of addiction?

Alexander: I have with nicotine, but not with any of the other substances I have used.

Ann: The whole idea of using psychedelics is to train yourself to a different kind of perception which you should be able to use without drugs. Most spiritual teachers say that you should develop the altered states in a natural way and not use drugs to do it. Sasha says that is the equivalent of saying you should never go to a symphony or listen to a recording. You should produce the music yourself and you should not use any other tools besides your own body.

Well heck! Life is made interesting by giving yourself different forms. Yes, it is wonderful to sing and play the flute yourself, but it is also wonderful to go to a symphony.

Rebecca: You do need to be disciplined and motivated to reproduce that state when you are not on the drug.

Ann: Right. You must have an incentive to develop your own abilities. Insight is something which Ive found can be learned. You can learn to observe your own thoughts. You begin to get a different relationship to time, to yourself, and to the mayfly. These things don't need drugs, but drugs can show you where you can go.

Rebecca: Although you both believe strongly in legalization, you do think that some guidelines must be established for drug use?

Alexander: Absolutely. Giving a drug to a person who is not developed enough to use it in the opinion of people who have worked with it, giving a drug without consent, giving out false information about a drug, all these need to be controlled.

Ann: I like to make the rather obvious comparison of psychedelics with sex. Nobody in their right mind would say that sex is bad for us, but no one would advise someone under a certain age to try it! There is a certain stage of growth you need to go through before you are ready for either.

David: Terence McKenna claims that there is a spirit or a conscious intelligence that dwells within certain psychedelic plants. In Pihkal, you discuss how at times you felt the presence of some entity or force guiding your work. Do you see this as being related to what Terence has claimed and how do you explain this phenomena?

Alexander: I think this is like the intuitive going through a darkroom without lights on and being able to find the door. You don't see in the dark and yet you know there's a door there. As you get more and more experienced at working with plants or working in the laboratory and designing new structures, you get more of a feel for why they are and what they are.

One of the beauties of organic chemistry is that you cannot make a relationship between a continuing change here and a continuing result there. You cannot extrapolate from one molecule to another with any more confidence than you can extrapolate from one plant to another. So you begin to assign certain characteristics to what you are working with. Is this talking to leprechauns? No. But it has the smell of that. (laughter)

Ann: I think that there are forms of energy that some people see as elves or fairies. Whether they see these or not seems to depend more on whether the culture they live in allows for seeing such things. The Irish are famous for it. Is this because a certain kind of energy associated with natural things is translating itself telepathically into an acceptable form for the human who is looking at it? It is an open question.

Alexander: How do you discover the action of a molecule? A molecule when its hatched is like a baby. There/s no personality there. As the baby develops, your relationship to the baby develops, and eventually it forms into something of its own shape and character.

The first time I made MDOH I distilled it as I like to do before I make the salt. I found that it began a threshold activity at around 80mg, but I didn't know that something was amiss. I ran some tests and discovered that when I did the distillation of MDOH I had gotten it sufficiently hot to split up the hydroxy group. I had made a mixture of the base without the hydroxy group which had gone on to the MDOH and become an oxine. The material I was left with was MDA. So I had accidentally rediscovered the property of MDA.

I went back and made MDOH again keeping the vacuum temperature down, and I came out of it with a brand new compound that I never would have made before. So from a divorced position I had to come back and reinstitute a rapport because the material I had thought I had met, I had not met. You don't discover these things, you interact and develop them together. If you want to incarnate elves into the materials, thats fine, but either way, its a relationship.

Rebecca: That sounds very similar to the way alchemists viewed their work.

Alexander: Very much so. I was listening to Terence McKenna years ago at Esalen. He was talking about how if a drug comes from nature its okay, but if it comes from a lab it is suspect. Suddenly he realized that I was sitting in the audience. (laughter) In essence I said, Terence, I am as natural as they come. To me it is not any different making a chemical in the laboratory that's new - that you can get to learn and interact with - than it is interacting with a plant.

David: As John Lilly said, "Plants are chemists, too."

Ann: Exactly, and some of them will kill you. Just because its natural doesn't mean its benign.

Alexander: I have studied alchemy a bit and it is very much about feedback. Who cares if you melt and fuse lead ten thousand times? At the end of it, you don't come out with anything but ten thousand times melted and fused lead! But the doing of it, that is meditation.

David: Do you see a relationship between alchemy and shamanism?

Alexander: Yes. They are both teachers. A shaman is a person who allows you to be healed by the interaction with himself, and alchemy is the same way.

Rebecca: Rupert Sheldrake proposes the idea that the characteristics of a compound develop through time creating a morphic field which influences all similar forms. Because of this idea, people like Terence McKenna suggest that newly developed drugs are soulless compared to something like psilocybin which has been used by shamans probably for thousands of years. How do you respond to this?

Ann: Thats like saying a newborn baby is soulless. There is a soul there, it just has to learn to relate.

Alexander: Initially I had a scientific reluctance to Rupert's theory, but Ive seen how he does it, and Ive grown to like the idea. He has complete candidness and honesty. He is trying to find things that don't fit into his theory, and that I like.

Rebecca: Have you experienced parallel discovery?

Alexander: Secrecy is anathema. Everything you do you share. But I remember the first time I got into sulfur. Nothing was going right, just black tars and terrible smells. I was working with a person in Indiana along the same lines, and about the same time we both developed separate psychedelics. It was almost as if the stars had aligned.

Rebecca: Both of you emphasize an omnijective view of reality rather than a strictly objective or subjective view.

Alexander: I am reading a marvelous book at the moment which talks about how up to the time of Galileo there was a complete synthesis of religious orthodoxy and science because it was part and parcel of the church. They broke apart because of Galileo and Copernicus contributions, and in a sense we have reconverged back to a synthesis of Genesis and the Big Bang, to a dogma which everyone takes on faith. And you don't allow the slightest challenge!

Rebecca: I interviewed the head of the Flat Earth Society, and I found it very liberating to allow myself to question something so engrained as the roundness of the earth! (laughter) In your book you both describe many mind-expanding experiences when you developed a sensitivity to the sacred life-forces. With this consciousness in mind, how do you feel about the practice of vivisection?

Alexander: I believe there are times when it is necessary. I used to do all my studies on rats and dogs but I wasn't learning enough to justify it so I stopped entirely. I think if it is possible to extend a persons life at the expense of an animal, then I think it is justified. Until recently, pigs were essential to maintain the life of people with diabetes. If you were a total vegetarian, would raising pigs to obtain insulin be justified to protect the lives of people who have diabetes?

Rebecca: No, it wouldn't. I know of a woman who claims to control her diabetes without insulin by eating something called bitter melon, which is native to Sri Lanka. There is much evidence to suggest that there is a vast reservoir of untapped medical lore and resources on the earth.

Ann: One of Lauren Van der Post books is about a race of pygmies in Africa. Before they kill an animal, they send out a deep thanks and gratitude to it asking to be forgiven for the fact that they are going to kill it. In a sense they enter an emotional contract with that animal. My feeling is that animal experimentation is necessary in this culture but I would pass a law that the only people allowed to work with animals in a laboratory would be those who love animals. If you love an animal, you are not going to be able to stand giving it pain.

In laboratories people are encouraged to not form any kind of attachment to the animals they are using. I think the opposite should be the case. Using an animals pain to develop cosmetics is inexcusable, but when it is to saving lives, I think that is a different question. I believe the whole environmental movement started with the taking of psychedelics in the 60s, because the first experience that everyone has is the oneness of nature.

Rebecca: Do you believe that there might be a teleological reason for why psychedelics exist?

Ann: Sure. How on earth did anyone ever discover the psychedelic properties of the peyote cactus or something that's only active as a snuff? Have you ever tasted peyote? Your instinct says, that's poisonous! Considering the fact that we create consensual reality, some part of us may have assigned certain plants the ability to open those doors.

Alexander: The evolution of the animal and plant kingdoms seem to be complementary to one another, but whereas you have the origin of the human in the Old World, 90 percent of psychedelic plants have been seen natively only in the New World. It is certainly not from a lack of diligence in searching for them! (laughter)

Rebecca: That is interesting. What procedures do you use when testing out a new drug and what do you do if everyone's experience is different?

Alexander: When I test a new drug on myself, I use extremely small levels with much space between each time to eliminate the effects of tolerance. When I get up to a level that I feel comfortable with, Ann and I share it and see if indeed we have the same responses. Then we introduce it to individuals within the research group.

We often find that some of the materials have radically different responses within the group. I had to abandon a whole family of compounds which I called the Alephs, because they were too erratic. Someone would have an over-stimulating experience on 2 mg and someone right next to them on 7 mg would experience nothing at all! We also have the occasional idiosyncratic difference from day to day of one person to one chemical.

TMA6 was a compound I had worked on and abandoned because it was not that interesting. We were exploring it because it was an opening to a new family of compounds. It was clearly active. You knew you were in an altered place, but you couldn't give it a name or a character. There were no visuals and no time distortion, nothing. So we threw it open to the group, and we were all up against the wall! When I went to take a pee in the bathroom, the wallpaper came out and shook hands! (laughter) Everyone had an intense experience.

Ann: Sasha goes through the boring stuff, tiny bits increased very gradually over weeks and weeks. I come in at the exciting point. (laughter) There are certain things that if we find, we don't pursue use of the substance. For example, if my emotions are flattened, its an absolute no-no to go on with it. Also, if we are not interested in touching each other, then there is something wrong. Also, of course, you learn to spot signs of impending nervous system trouble, like the possibility of a convulsion.

Alexander: Its like soldiers marching across the bridge. If you break step, youre not going to have the rest of the bridge getting to some resonance which could lead to a catastrophic event. You search out your thought patterns and abort them before they come to any consequence. Then you start another thought pattern and stop it. If you don't let things consummate, that diffuses things, and pretty soon you realize that its not necessary any more. The other answer is phenobarb which is much easier. (laughter)

Ann: The group doesn't get any of these things until we've gone up to a plus 3 and usually beyond that to the point where its too much.

So we know for sure that it is not going to attack our nervous systems.

David: What are some of the basic guidelines that you would recommend to an individual who was experimenting with psychedelics?

Alexander: Learn everything you can about the material and stay away from all information that is clearly geared to encourage or discourage its use.

Ann: Doing your first experience with a very trusted friend who has taken this substance before is very important. That sort of companionship can turn a very bad trip into a very good learning experience. Your psyche is very eager to have you learn things, and if you can develop an acceptance and a calmness, you can overcome a lot.

David: What type of drugs do you see being developed in the future, and how do you see pharmacological tools being used to expand potential in the areas of creativity, intelligence and spiritual understanding?

Alexander: In this direction I think anything that the human is capable of doing through the mind is duplicable pharmacologically, it is all chemistry upstairs. I think anything from insight to paranoia, to joy to fear, can all be reproduced chemically.

The fact that there are specific receptor sites for specific materials in the body which duplicate the actions of drugs from outside the body implies that those receptor sites at which these drugs operate are there because the human produces one for that same purpose.

Ann: I think that depending on the way you interact with any particular psychedelic, creativity and imagination can arise. Basically you are giving yourself permission to use these powers. I can't see a particularly creative psychedelic.

David: But they may be developed with more specificity. You developed a drug whose only property was to create auditory distortion.

Alexander: Right, that is a good example. I am intrigued by that one because most of the spontaneous schizophrenic states have auditory rather than visual components. If there is a physical correlate to schizophrenia you could deposit this material in a person and see where it accumulates. You could play strange noises and see if it accumulated faster or slower.

Rebecca: How many psychedelics have you synthesized?

Alexander: Around 100.

Rebecca: And how many of those are illegal?

Alexander: About fifteen. The analog law will label a drug illegal on the grounds of it being substantially similar to an already existing illegal drug. I was once asked in a drug case down south if two drugs were substantially similar. I said that the question had no meaning. The chemist, who came from the Ventura County crime lab, said that two things are substantially similar if they are over fifty percent identical. I just abandoned ship at that point. Its a lot of gibberish!

David: How has your relationship influenced your psychedelic journeys?

Ann: If you are going to do psychedelic exploring, the ideal is to have a partner who is on the same wavelength. There is, needless to say, a certain amount of vulnerability when you take these substances, and you have to totally trust the other person. The only disadvantage is that I suspect we pick up each others responses a little faster than we should.

Alexander: I had one experience that really startled me. I got up in the morning and went to wash the dishes from the night before, and I realized I was not at baseline. It was nice, but I was wondering, What caused this? Sasha came in, and I was wondering if I should say anything to him when he came up with the information that he had taken a sample of a new drug that morning!

David: Do you think you might have been exuding pheromones, which the other person was picking up?

Alexander: That is possible, but you are normally unaware of the extraordinary vocabulary of body language. Just the way people carry themselves, or the way they respond to a stimulus can give them away. And if Ann is washing dishes, I know we have a problem. (laughter)

David: What projects are you currently working on?

Alexander: Tryptamines. (laughter)

http://www.mavericksofthemind.com/shu-int.htm

Last edited: