Psilocybin-assisted treatment of alcohol use disorder*

Michael Bogenschutz, Samantha Podrebarac, Jessie Duane, Sean Amegadzie, Tara Malone, Lindsey Owens, Stephen Ross and Sarah Mennenga

After 40 years, clinical research has resumed on the use of classic hallucinogens to treat addiction. Following completion of a small open-label feasibility study, we are currently conducting a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of psilocybin-assisted treatment of alcohol use disorder. Although treatment effects cannot be analyzed until the study is complete, descriptive case studies provide a useful window into the therapeutic process of psychedelic-assisted treatment of addiction. Here we describe treatment trajectories of 3 participants in the ongoing trial to illustrate the range of experiences and persisting effects of psilocybin treatment.

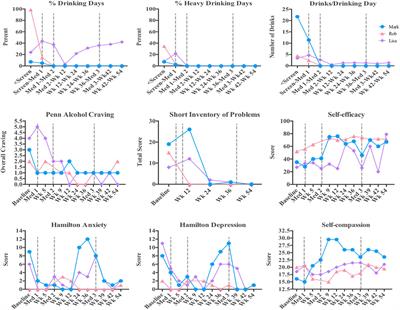

Although it is difficult to generalize from a few cases, several qualitative conclusions can be drawn from the data presented here. Although participants often find it difficult to describe much of their psilocybin experience, pivotal moments tend to be individualized, extremely vivid, and memorable. Often, the qualitative content extends beyond the clinical problem that is being addressed. The participants discussed in this paper experienced acute and lasting alterations in their perceptions of self, in the quality of their baseline consciousness, and in their relationship with alcohol and drinking. In these cases, experiences of catharsis, forgiveness, self-compassion, and love were at least as salient as classic mystical content. Finally, feelings of increased “spaciousness” or mindfulness, and increased control over choices and behavior were reported following the drug administration sessions. Ultimately, psilocybin-assisted treatment appears to elicit experiences that are extremely variable, yet seem to meet the particular needs of the individual.

Mark

Mark was a white male in his 20s living with his parents and working full-time at the time of enrollment. His binge drinking began in his teens and intensified into adulthood. He reported frequent blackouts and occasional absences from work due to drinking episodes that lasted for days. At baseline, he reported drinking on six of the past 84 days, with an average of 22 drinks per drinking day. Mark had made multiple unsuccessful attempts at treatment, and had attended hundreds of AA meetings. Mark started the study with the intention of attaining complete abstinence from alcohol. He said,

“I just want to stop and have a normal life.”

During the first medication session, Mark encountered his anxiety and fears associated with failure. Though the effects were mild and difficult for him to communicate in words, he said,

“It was almost like finding the Holy Grail and the answer to all of life’s questions.” Self-report assessments revealed that he had experienced a session of moderately high intensity. In the month that followed, Mark remained abstinent and was surprised at how easy this was and how little he thought about alcohol.

Mark’s second medication session was higher in both dose and intensity. He was confronted by the harmful effects that his drinking had on himself and others. He stated that

“at one point, I felt I could have cried for joy,” when realizing that he was being given “a new slate.” In the following weeks, he reported increased motivation and drive and a strong desire to contribute to the world in a meaningful way. He said,

“I feel like I’m maturing. Maybe a part of me died when I gave up alcohol.”

Mark remained abstinent during the 7 months following the second medication session. He opted to have the third open-label medication session with the hope that it would help with his work-related anxiety. He described the experience as “a crash course” in dealing with feelings of disappointment, regret, shame, and unworthiness. He also reported “a couple of eureka moments,” and said that the session ended with “calmness, comfort, and reassurance.” He said,

“I wouldn’t be surprised if I never drank again” and added,

“I got exactly what I need out of the experience.” One month after this session, he remained abstinent and expressed a great deal of gratitude for being able to participate in the study. Two years from his initial intake, Mark contacted the study team to report that he continued to remain abstinent.

Rob

Rob was an African–American male in his 40s who was unemployed at enrollment in the trial. He had been drinking heavily since college, and his alcohol use had caused him to discontinue his studies and his promising athletic career. He was raised in a family that drank heavily, and his father had died due to complications associated with alcoholism. Since the passing of his father, Rob became very concerned about his own health in relation to his own alcohol use. His drinking was also in direct conflict with his Muslim faith. At the time of enrollment he had consumed alcohol on 83 of 84 days, with an average of four drinks per drinking day. He was able to achieve 8 days of sobriety prior to his first medication session.

Rob’s first medication session was dominated by strong nausea and abdominal pain. During the peak effects of the study medication, he sat upright, attempting to vomit, but was only able to spit repeatedly into a wastebasket. In debriefing the following day, he reported briefly sensing the presence of his father and communication of mutual forgiveness. However, upon remembering that his religion did not permit the living to communicate with the dead, he decided to resist the effects of the drug and began to feel ill. He continued to combat the drug effects for the remainder of the session. Eventually he became too exhausted to continue fighting the drug’s effects, at which point he lay down on the couch and gradually began to experience increased comfort.

In subsequent therapy sessions, Rob reported that the medication session had been the most painful experience of his life, commenting that “nothing ever felt worse than those 2 hours.” He was pleased to have “weathered the storm,” and as a result of the “ordeal,” he reported an increased sense of urgency to get his life moving in a positive direction. He acknowledged that he judged himself harshly for not making more of an effort to keep his life on track in the past. However, as he gained confidence from the progress made in his life, he began to feel more forgiving of himself. He was hired at a new job within 4 weeks of the medication session and also enrolled in school. Rob also reported that he valued the moment of contact with his father, and that the session had affirmed and strengthened his resolve to live according to his religious principles. He declined the second and third medication sessions, but completed all other aspects of the therapy and assessments for the study. At his last follow-up visit (54 weeks after beginning the study) he remained abstinent with little desire to drink and happily reported that he was employed and pursuing a degree in social work.

Lisa

Lisa was a Latin-American female in her 50s with a family history of alcoholism, physical and emotional abuse, abandonment, and neglect. Her problem drinking began around age thirty and resulted in social isolation, hangovers, strong feelings of guilt and shame, and severe self-critical thoughts. At the start of the study she expressed concern regarding the effects that drinking was having on her physical and mental health. Lisa had made multiple previous attempts at treatment, and attended a total of 29 AA meetings, with the most recent meeting in 1993. At study enrollment, she had been drinking on 20 out of the previous 84 days, averaging three drinks per drinking day.

During the initial session, Lisa spent time exploring her mother’s neglect and abuse, but noted that she did not experience any antagonism toward her. She examined the negative feelings that she harbored for herself and feelings of alienation from God. She remembered an inner voice exclaiming to God,

“Why did you leave me?” to which God responded,

“Why are you so controlling?” After this session, she noticed a significant brightening of her mood and a lasting decrease in self-critical thinking. In response to God’s message about her controlling tendencies, Lisa chose not to commit herself to complete abstinence at that time, though she found herself drinking much less.

In the second session, Lisa received a higher dose of medication and experienced an amplification of thought moving her into a confused and chaotic state. Underneath the chaotic thinking, she identified a deep well of overwhelming sadness. She was able to eventually surrender control over her thoughts and entered into a state of peacefulness, until her thoughts quieted completely. She heard her own inner voice rupturing the quiet, whispering into her ear:

“I’m going to tell you a secret. It’s the worst-kept secret in the universe because everyone knows it but you. You are a perfect creation of the universe.” At that moment she felt that everything in existence was unified and was made of love, though a part of her remained reluctant to fully believe this to be true. The voice repeatedly presented her with this reality, asking

“Do you believe this?” over and over, until each one of her objections had been addressed and dismissed. She examined herself and found that she finally did accept this to be true, which propelled her into a state of profound self-acceptance and wellbeing. She later said,

“All there is is love, this is all that you are, this is all that matters.”

Following her medication session, Lisa reported that her self-critical thoughts had dissolved and that alcohol had lost almost all of its appeal. She said that the medication sessions had illuminated how she had been unkind to her body and had been harming herself with alcohol. She noted her ability to manage stress and found that she was making time to care for herself through socialization, relaxation, and a resumed meditation practice. She reported improved concentration, a lack of negative self-talk, decreased anxiety, and a spacious quality of mind, stating that,

“the noise can bubble up but it doesn’t overwhelm me. When these little anxieties walk in this big room they seem so little. I feel peaceful, and I feel safe. It feels good to be in my body. I’ve found myself taking wonderful breaths. The negative remarks don’t even pop into my head.”

Lisa elected to participate in the open-label session. Before her third dosing session, she reported a dramatic and sustained increase in her anxiety, which she attributed to the results of the recent presidential election. She reported that the positive effects from the two previous sessions had persisted, and that alcohol was no longer problematic. She described being able to consume an occasional glass of wine while remaining free from the compulsion to overindulge. The only instance of drinking to excess was on one isolated occasion, which was the night of the election. Her intention for the third session was to find relief from her apprehension regarding the election outcome. She described the medication experience as consisting of several hours of pure and intense anxiety, with very little specific thought or perceptual content. The following day she reported that her anxiety had lifted and that she was feeling calm and peaceful. At 54 weeks, Lisa reported a persisting reduction in alcohol consumption and alleviated anxiety.

*From the article here :

After a hiatus of some 40 years, clinical research has resumed on the use of classic hallucinogens to treat addiction. Following completion of a small open-label feasibility study, we are currently conducting a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial of psilocybin-assisted treatment of...

www.frontiersin.org