"So far in this book I have mainly described my scientific work and matters relating to my professional activity. But this work, by its very nature, had repercussions on my own life and personality, not least because it brought me into contact with interesting and important contemporaries. I have already mentioned some of them—Timothy Leary, Rudolf Gelpke, Gordon Wasson. Now, in the pages that follow, I would like to emerge from the natural scientist's reserve, in order to portray encounters which were personally meaningful to me and which helped me solve questions posed by the substances I had discovered."

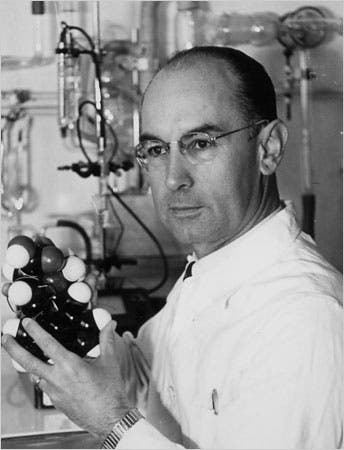

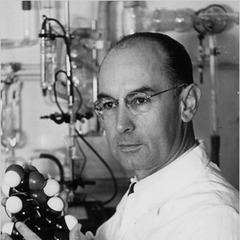

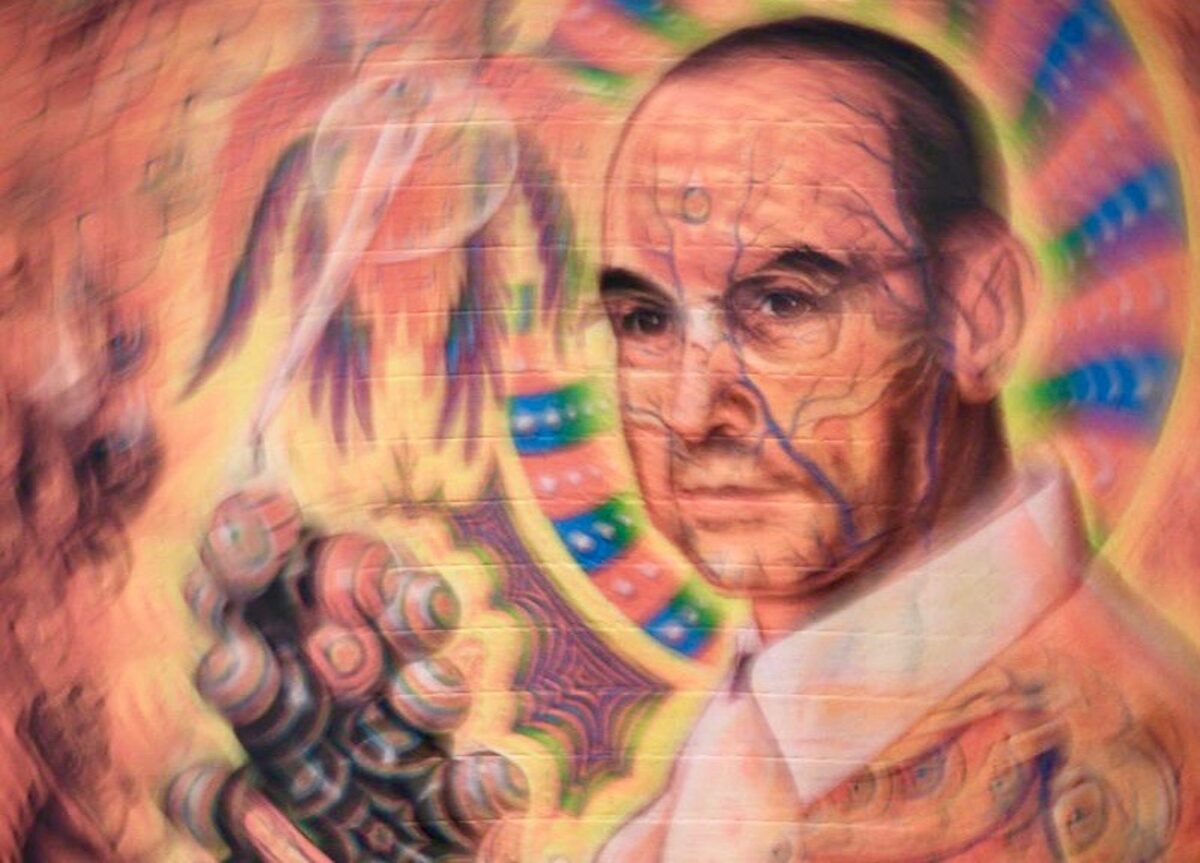

A.H.

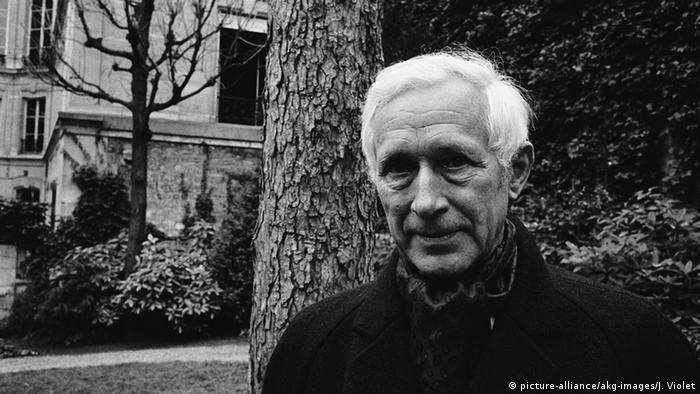

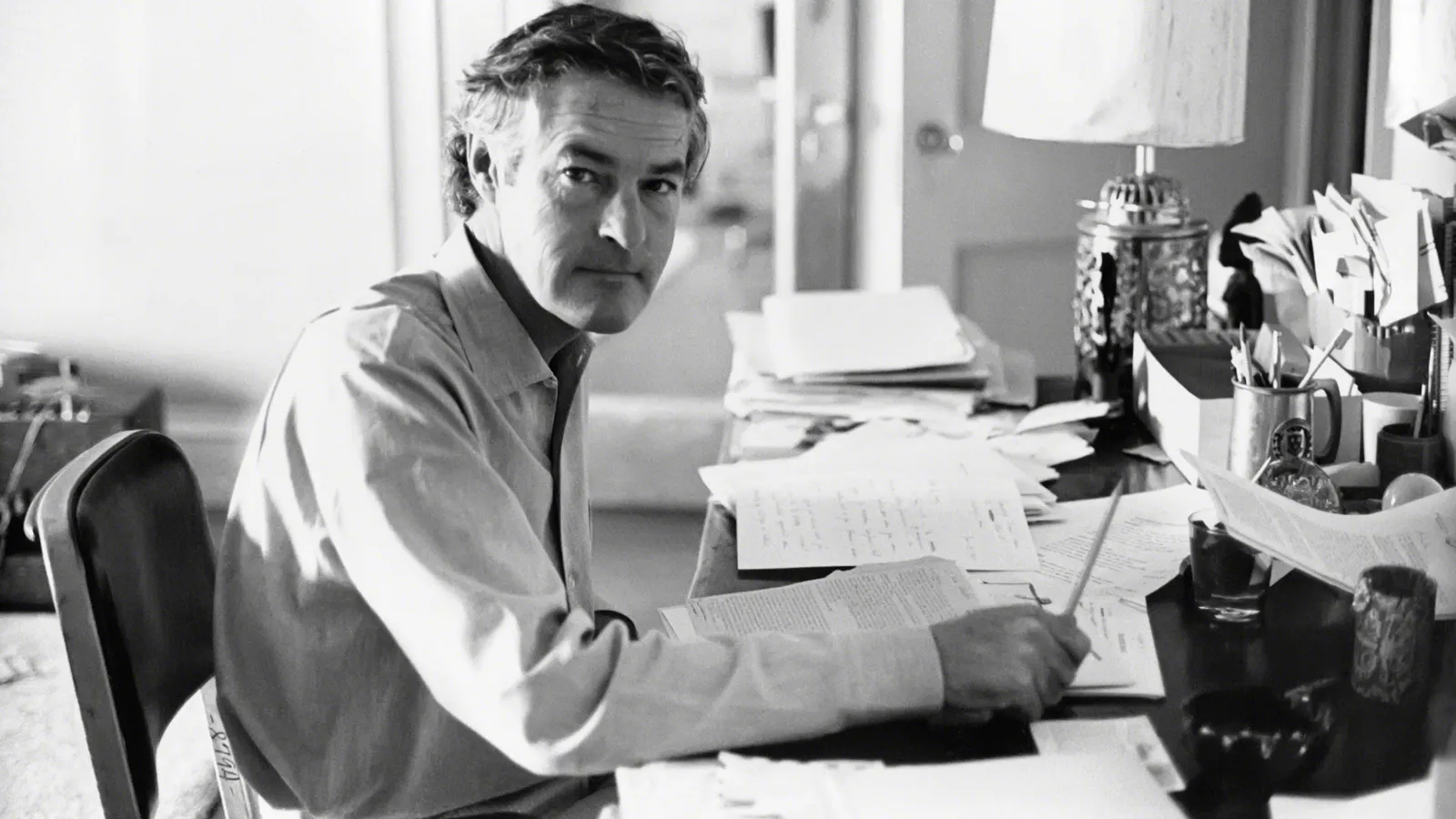

Radiance from Ernst Jünger

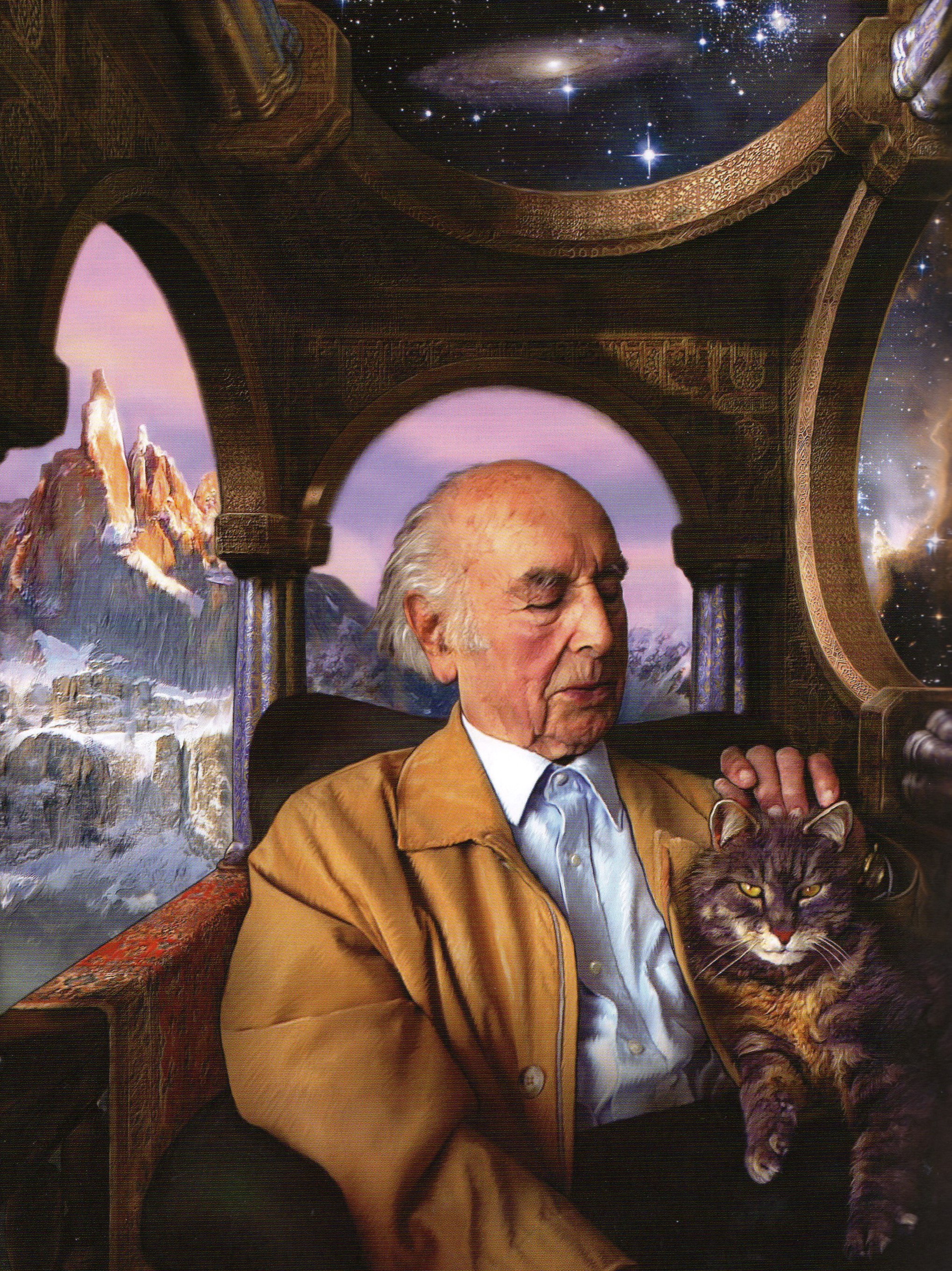

Radiance is the perfect term to express the influence that Ernst Jünger's literary work and personality have had on me. In the light of his perspective, which stereoscopically comprises the surfaces and depths of things, the world I knew took on a new, translucent splendor. That happened a long time before the discovery of LSD and before I came into personal contact with this author in connection with hallucinogenic drugs.

My enchantment with Ernst Jünger began with his book Das Abenteuerliche Herz [The adventurous heart]. Again and again in the last forty years I have taken up this book. Here more than ever, in themes that weigh more lightly and lie closer to me than war and a new type of human being (subjects of Jünger's earlier books), the beauty and magic of Jünger's prose was opened to me-descriptions of flowers, of dreams, of solitary walks; thoughts about chance, the future, colors, and about other themes that have direct relation to our personal lives. Everywhere in his prose the miracle of creation became evident, in the precise description of the surfaces and, in translucence, of the depths; and the uniqueness and the imperishable in every human being was touched upon. No other writer has thus opened my eyes.

Drugs were also mentioned in Das Abenteuerliche Herz. Many years passed, however, before I myself began to be especially interested in this subject, after the discovery of the psychic effects of LSD.

My first correspondence with Ernst Jünger had nothing to do with the context of drugs; rather I once wrote to him on his birthday, as a thankful reader.

---

Bottmingen, 29 March 1947

Dear Mr. Jünger,

As one richly endowed by you for years, I wished to send a jar of honey to you for your birthday. But I did not have this pleasure, because my export license has been refused in Bern.

The gift was intended less as a greeting from a country in which milk and honey still flow, than as a reminiscence of the enchanting sentences in your book Auf den Marmorklippen (On the Marble Cliffs), where you speak of the "golden bees."

The book mentioned here had appeared in 1939, just shortly before the outbreak of World War II. Auf den Marmorklippen is not only a masterpiece of German prose, but also a work of great significance because in this book the characteristics of tyrants and the horror of war and nocturnal bombardment are described prophetically, in poetic vision.

In the course of our correspondence, Ernst Jünger also inquired about my LSD studies, of which he had learned through a friend. Thereupon I sent him the pertinent publications, which he acknowledged with the following comments:

Kirchhorst, 3/3/1948

. . . together with both enclosures concerning your new phantasticum. It seems indeed that you have entered a field that contains so many tempting mysteries.

Your consignment came together with the Confessions of an English Opium Eater, that has just been published in a new translation. The translator writes me that his reading of Das Abenteuerliche Herz stimulated him to do his work.

As far as I am concerned, my practical studies in this field are far behind me. These are experiments in which one sooner or later embarks on truly dangerous paths, and may be considered lucky to escape with only a black eye.

What interested me above all was the relationship of these substances to productivity. It has been my experience, however, that creative achievement requires an alert consciousness, and that it diminishes under the spell of drugs. On the other hand, conceptualization is important, and one gains insights under the influence of drugs that indeed are not possible otherwise. I consider the beautiful essay that Maupassant has written about ether to be such an insight. Moreover, I had the impression that in fever one also discovers new landscapes, new archipelagos, and a new music, that becomes completely distinct when the "customs station" ["An der Zollstation" [At the custom station], the title heading of a section in Das Abenteuerliche Herz (2d ed.) that concerns the transition from life to death.] appears. For geographic description, on the other hand, one must be fully conscious. What productivity means to the artist, healing means to the physician. Accordingly, it also may suffice for him that he sometimes enters the regions through the tapestries that our senses have woven. Moreover, I seem to perceive in our time less of a taste for the phantastica than for the energetica—amphetamine, which has even been furnished to fliers and other soldiers by the armies, belongs to this group. Tea is in my opinion a phantasticum, coffee an energeticum—tea therefore possesses a disproportionately higher artistic rank. I notice that coffee disrupts the delicate lattice of light and shadows, the fruitful doubts that emerge during the writing of a sentence. One exceeds his inhibitions. With tea, on the other hand, the thoughts climb genuinely upward.

So far as my "studies" are concerned, I had a manuscript on that topic, but have since burned it. My excursions terminated with hashish, that led to very pleasant, but also to manic states, to oriental tyranny....

Soon afterward, in a letter from Ernst Jünger I learned that he had inserted a discourse about drugs in the novel Heliopolis, on which he was then working. He wrote to me about the drug researcher who figures in the novel:

Among the trips in the geographical and metaphysical worlds, which I am attempting to describe there, are those of a purely sedentary man, who explores the archipelagos beyond the navigable seas, for which he uses drugs as a vehicle. I give extracts from his log book. Certainly, I cannot allow this Columbus of the inner globe to end well-he dies of a poisoning. Avis au lecteur.

The book that appeared the following year bore the subtitle Ruckblick auf eine Stadt [Retrospective on a city], a retrospective on a city of the future, in which technical apparatus and the weapons of the present time were developed still further in magic, and in which power struggles between a demonic technocracy and a conservative force took place. In the figure of Antonio Peri, Jünger depicted the mentioned drug researcher, who resided in the ancient city of Heliopolis.

He captured dreams, just like others appear to chase after butterflies with nets. He did not travel to the islands on Sundays and holidays and did not frequent the taverns on Pagos beach. He locked himself up in his studio for trips into the dreamy regions. He said that all countries and unknown islands were woven into the tapestry. The drugs served him as keys to entry into the chambers and caves of this world. In the course of the years he had gained great knowledge, and he kept a log book of his excursions. A small library adjoined this studio, consisting partly of herbals and medicinal reports, partly of works by poets and magicians. Antonio tended to read there while the effect of the drug itself developed. . . . He went on voyages of discovery in the universe of his brain....

In the center of this library, which was pillaged by mercenaries of the provincial governor during the arrest of Antonio Peri, stood The great inspirers of the nineteenth century: De Quincey, E.T.A. Hoffmann, Poe, and Baudelaire. Yet there were also books from the ancient past: herbals, necromancy texts, and demonology of the middle-aged world. They included the names Albertus Magnus, Raimundus Lullus, and Agrippa of Nettesheym.... Moreover, there was the great folio De Praestigiis Daemonum by Wierus, and the very unique compilations of Medicus Weckerus, published in Basel in 1582....

In another part of his collection, Antonio Peri seemed to have cast his attention principally "on ancient pharmacology books, formularies and pharmacopoeias, and to have hunted for reprints of journals and annals. Among others was found a heavy old volume by the Heidelberg psychologists on the extract of mescal buttons, and a paper on the phantastica of ergot by Hofmann-Bottmingen...."

In the same year in which Heliopolis came out, I made the personal acquaintance of the author. I went to meet Ernst Jünger in Ravensburg, for a Swiss sojourn. On a wonderful fall journey in southern Switzerland, together with mutual friends, I experienced the radiant power of his personality.

Two years later, at the beginning of February 1951, came the great adventure, an LSD trip with Ernst Jünger. Since, up until that moment, there were only reports of LSD experiments in connection with psychiatric inquiries, this experiment especially interested me, because this was an opportunity to observe the effects of LSD on the artistic person, in a nonmedical milieu. That was still somewhat before Aldous Huxley, from the same perspective, began to experiment with mescaline, about which he then reported in his two books The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell.

In order to have medical aid on hand if necessary, I invited my friend, the physician and pharmacologist Professor Heribert Konzett, to participate. The trip took place at 10:00 in the morning, in the living room of our house in Bottmingen. Since the reaction of such a highly sensitive man as Ernst Jünger was not foreseeable, a low dose was chosen for this first experiment as a precaution, only 0.05 mg. The experiment then, did not lead into great depths.

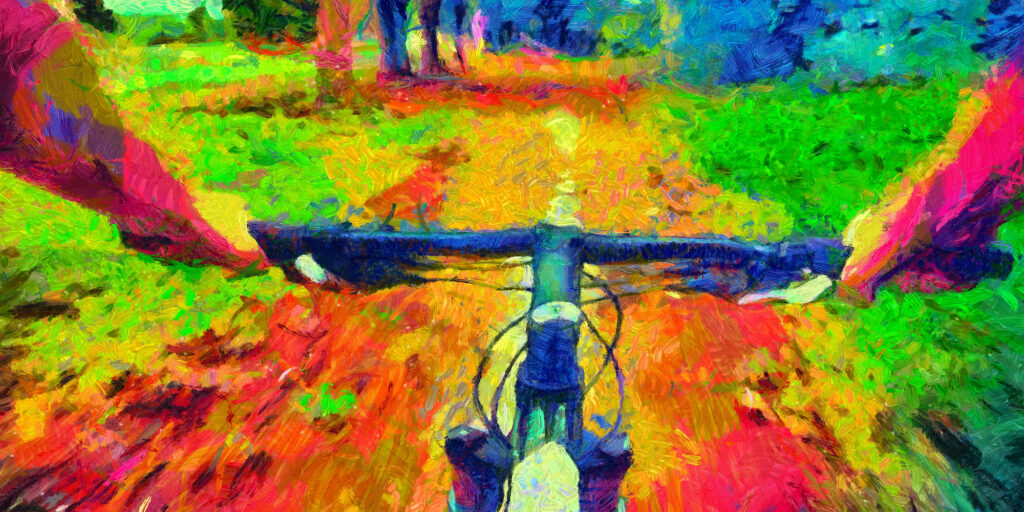

The beginning phase was characterized by the intensification of aesthetic experience. Red-violet roses were of unknown luminosity and radiated in portentous brightness. The concerto for flute and harp by Mozart was perceived in its celestial beauty as heavenly music. In mutual astonishment we contemplated the haze of smoke that ascended with the ease of thought from a Japanese incense stick. As the inebriation became deeper and the conversation ended, we came to fantastic reveries while we lay in our easy chairs with closed eyes. Ernst Jünger enjoyed the color display of oriental images: I was on a trip among Berber tribes in North Africa, saw colored caravans and lush oases. Heribert Konzett, whose features seemed to me to be transfigured, Buddha-like, experienced a breath of timelessness, liberation from the past and the future, blessedness through being completely here and now.

The return from the altered state of consciousness was associated with strong sensitivity to cold. Like freezing travelers, we enveloped ourselves in covers for the landing. The return to everyday reality was celebrated with a good dinner, in which Burgundy flowed copiously.

This trip was characterized by the mutuality and parallelism of our experiences, which were perceived as profoundly joyful. All three of us had drawn near the gate to an experience of mystical being; however, it did not open. The dose we had chosen was too low. In misunderstanding this reason, Ernst Jünger, who had earlier been thrust into deeper realms by a high dose of mescaline, remarked: "Compared with the tiger mescaline, your LSD, is, after all, only a house cat." After later experiments with higher doses of LSD, he revised this estimation.

Jünger has assimilated the mentioned spectacle of the incense stick into literature, in his story Besuch auf Gotenhotm [Visit to Godenholm], in which deeper experiences of drug inebriation also play a part: Schwarzenberg burned an incense stick, as he sometimes did, to clear the air. A blue plume ascended from the tip of the stick. Moltner looked at it first with astonishment, then with delight, as if a new power of the eyes had come to him. It revealed itself in the play of this fragrant smoke, which ascended from the slender stick and then branched out into a delicate crown. It was as if his imagination had created it-a pallid web of sea lilies in the depths, that scarcely trembled from the beat of the surf. Time was active in this creation-it had circled it, whirled about it, wreathed it, as if imaginary coins rapidly piled up one on top of another. The abundance of space revealed itself in the fiber work, the nerves, which stretched and unfolded in the height, in a vast number of filaments.

Now a breath of air affected the vision, and softly twisted it about the shaft like a dancer. Moltner uttered a shout of surprise. The beams and lattices of the wondrous flower wheeled around in new planes, in new fields. Myriads of molecules observed the harmony. Here the laws no longer acted under the veil of appearance; matter was so delicate and weightless that it clearly reflected them. How simple and cogent everything was. The numbers, masses and weights stood out from matter. They cast off the raiments. No goddess could inform the initiates more boldly and freely. The pyramids with their weight did not reach up to this revelation. That was Pythagorean luster. No spectacle had ever affected him with such a magic spell.

This deepened experience in the aesthetic sphere, as it is described here in the example of contemplation of a haze of blue smoke, is typical of the beginning phase of LSD inebriation, before deeper alterations of conscious begin.

I visited Ernst Jünger occasionally in the following years, in Wilfingen, Germany, where he had moved from Ravensburg; or we met in Switzerland, at my place in Bottmingen, or in Bundnerland in southeastern Switzerland. Through the shared LSD experience our relations had deepened. Drugs and problems connected with them constituted a major subject of our conversation and correspondence, without our having made further practical experiments in the meantime.

We exchanged literature about drugs. Ernst Jünger thus let me have for my drug library the rare, valuable monograph of Dr. Ernst Freiherrn von Bibra, Die Narkotischen Genussmittel und der Mensch [Narcotic pleasure drugs and man] printed in Nuremburg in 1855. This book is a pioneering, standard work of drug literature, a source of the first order, above all as relates to the history of drugs. What von Bibra embraces under the designation "Narkotischen Genussmittel" are not only substances like opium and thorn apple, but also coffee, tobacco, kat, which do not fall under the present conception of narcotics, any more than do drugs such as coca, fly agaric, and hashish, which he also described.

Noteworthy, and today still as topical as at the time, are the general opinions about drugs that von Bibra contrived more than a century ago: The individual who has taken too much hashish, and then runs frantically about in the streets and attacks everyone who confronts him, sinks into insignificance beside the numbers of those who after mealtime pass calm and happy hours with a moderate dose; and the number of those who are able to overcome the heaviest exertions through coca, yes, who were possibly rescued from death by starvation through coca, by far exceed the few coqueros who have undermined their health by immoderate use. In the same manner, only a misplaced hypocrisy can condemn the vinous cup of old father Noah, because individual drunkards do not know how to observe limit and moderation.

From time to time I advised Ernst Jünger about actual and entertaining events in the field of inebriating drugs, as in my letter of September 1955: . . . Last week the first 200 grams of a new drug arrived, whose investigation I wish to take up. It involves the seeds of a mimosa (Piptadenia peregrina Benth,) that is used as a stimulating intoxicant by the Indians of the Orinoco. The seeds are ground, fermented, and then mixed with the powder of burned snail shells. This powder is sniffed by the Indians with the help of a hollow, forked bird bone, as already reported by Alexander von Humboldt in Reise nach den Aequinoctiat-Gegenden des Neuen Kontinents [Voyage to the equinoctial regions of the new continent] (Book 8, Chapter 24). The warlike tribe, the Otomaco, especially use this drug, called niopo, yupa, nopo or cojoba, to an extensive degree, even today. It is reported in the monograph by P. J. Gumilla, S. J. (El Orinoco Ilustrado, 1741): "The Otomacos sniffed the powder before they went to battle with the Caribes, for in earlier times there existed savage wars between these tribes.... This drug robs them completely of reason, and they frantically seize their weapons. And if the women were not so adept at holding them back and binding them fast, they would daily cause horrible devastation. It is a terrible vice.... Other benign and docile tribes that also sniff the yupa, do not get into such a fury as the Otomacos, who through self-injury with this agent made themselves completely cruel before combat, and marched into battle with savage fury."

I am curious how niopo would act on people like us. Should a niopo session one day come to pass, then we should on no account send our wives away, as on that early spring reverie [The LSD trip of February 1951 is meant here.], that they may bind us fast if necessary....

Chemical analysis of this drug led to isolation of active principles that, like the ergot alkaloids and psilocybin, belong to the group of indole alkaloids, but which were already described in the technical literature, and were therefore not investigated further in the Sandoz laboratories. [Translator's note: The active principles of niopo are DMT (N,N-dimethyltryptamine) and its congeners. DMT was first prepared in 1931 by Manske.] The fantastic effects described above appeared to occur only with the particular manner of use as snuff powder, and also seemed to be related, in all probability, to the psychic structure of the Indian tribes concerned.

---

Ambivalence of Drug Use

Fundamental questions of drug problems were dealt with in the following correspondence. :

Bottmingen, 16 December 1961

Dear Mr. Jünger,

On the one hand, I would have the great desire, besides the natural-scientific, chemical-pharmacological investigation of hallucinogenic substances, also to research their use as magic drugs in other regions.... On the other hand, I must admit that the fundamental question very much occupies me, whether the use of these types of drugs, namely of substances that so deeply effect our minds, could not indeed represent a forbidden transgression of limits. As long as any means or methods are used, which provide only an additional, newer aspect of reality, surely there is nothing to object to in such means; on the contrary, the experience and the knowledge of further facets of the reality only makes this reality ever more real to us. The question exists, however, whether the deeply affecting drugs under discussion here will in fact only open an additional window for our senses and perceptions, or whether the spectator himself, the core of his being, undergoes alterations. The latter would signify that something is altered that in my opinion should always remain intact. My concern is addressed to the question, whether the innermost core of our being is actually unimpeachable, and cannot become damaged by whatever happens in its material, physical-chemical, biological and psychic shells-or whether matter in the form of these drugs displays a potency that has the ability to attack the spiritual center of the personality, the self. The latter would have to be explained by the fact that the effect of magic drugs happens at the borderline where mind and matter merge-that these magic substances are themselves cracks in the infinite realm of matter, in which the depth of matter, its relationship with the mind, becomes particularly obvious. This could be expressed by a modification of the familiar words of Goethe:

"Were the eye not sunny,

It could never behold the sun;

If the power of the mind were not in matter,

How could matter disturb the mind."

This would correspond to cracks which the radioactive substances constitute in the periodic system of the elements, where the transition of matter into energy becomes manifest. Indeed, one must ask whether the production of atomic energy likewise represents a transgression of forbidden limits.

A further disquieting thought, which follows from the possibility of influencing the highest intellectual functions by traces of a substance, concerns free will.

The highly active psychotropic substances like LSD and psilocybin possess in their chemical structure a very close relationship with substances inherent in the body, which are found in the central nervous system and play an important role in the regulation of its functions. It is therefore conceivable that through some disturbance in the metabolism of the normal neurotransmitters, a compound like LSD or psilocybin is formed, which can determine and alter the character of the individual, his world view and his behavior. A trace of a substance, whose production or nonproduction we cannot control with our wills, has the power to shape our destiny. Such biochemical considerations could have led to the sentence that Gottfried Benn quoted in his essay "Provoziertes Leben" [Provoked life]: "God is a substance, a drug!"

On the other hand, it is well known that substances like adrenaline, for example, are formed or set free in our organism by thoughts and emotions, which for their part determine the functions of the nervous system. One may therefore suppose that our material organism is susceptible to and shaped by our mind, in the same way that our intellectual essence is shaped by our biochemistry. Which came first can indeed no better be determined than the question, whether the chicken came before the egg.

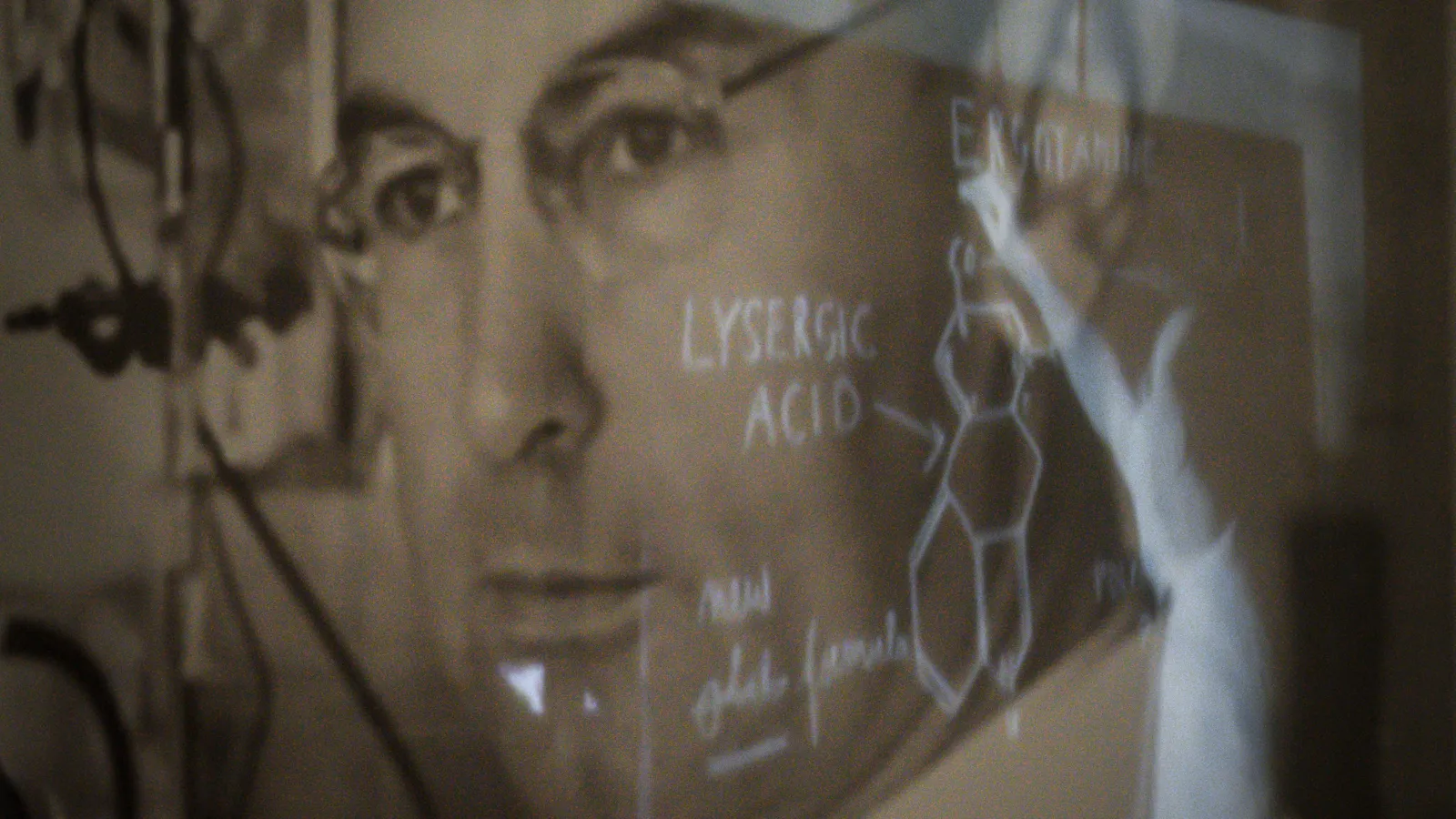

In spite of my uncertainty with regard to the fundamental dangers that could lie in the use of hallucinogenic substances, I have continued investigations on the active principles of the Mexican magic morning glories, of which I wrote you briefly once before. In the seeds of this morning glory, that were called ololiuhqui by the ancient Aztecs, we found as active principles lysergic acid derivatives chemically very closely related to LSD. That was an almost unbelievable finding. I have all along had a particular love for the morning glories. They were the first flowers that I grew myself in my little child's garden. Their blue and red cups belong to the first memories of my childhood.

I recently read in a book by D. T. Suzuki, Zen and Japanese Culture, that the morning glory plays a great role in Japan, among the flower lovers, in literature, and in graphic arts. Its fleeting splendor has given the Japanese imagination rich stimulus. Among others, Suzuki quotes a three- line poem of the poetess Chiyo (1702-75), who one morning went to fetch water from a neighbor's house, because . . . "My trough is captivated by a morning glory blossom, So I ask after water."

The morning glory thus shows both possible ways of influencing the mind-body-essence of man: in Mexico it exerts its effects in a chemical way as a magic drug, while in Japan it acts from the spiritual side, through the beauty of its flower cups.

---

Wilflingen, 17 December 1961

Dear Mr. Hofmann,

I give you my thanks for your detailed letter of 16 December. I have reflected on your central question, and may probably become occupied with it on the occasion of the revision of An der Zeitmauer [At the wall of time]. There I intimated that, in the field of physics as well as in the field of biology, we are beginning to develop procedures that are no longer to be understood as advances in the established sense, but that rather intervene in evolution and lead forth in the development of the species. Certainly I turn the glove inside out, for I suppose that it is a new world age, which begins to act evolutionarily on the prototypes. Our science with its theories and discoveries is therefore not the cause, rather one of the consequences of evolution, among others. Animals, plants, the atmosphere and the surfaces of planets will be concerned simultaneously. We do not progress from point to point, rather we cross over a line.

The risk that you indicated is well to be considered. However, it exists in every aspect of our existence. The common denominator appears now here, now there.

In mentioning radioactivity, you use the word crack. Cracks are not merely points of discovery, but also points of destruction. Compared to the effects of radiation, those of the magical drugs are more genuine and much less rough. In classical manner they lead us beyond the humane. Gurdjieff has already seen that to some extent. Wine has already changed much, has brought new gods and a new humanity with it. But wine is to the new substances as classical physics is to modern physics. These things should only be tried in small circles. I cannot agree with the thoughts of Huxley, that possibilities for transcendence could here be given to the masses. Indeed, this does not involve comforting fictions, but rather realities, if we take the matter earnestly. And few contacts will suffice here for the setting of courses and guidance. It also transcends theology and belongs in the chapter of theogony, as it necessarily entails entry into a new house, in the astrological sense. At first, one can be satisfied with this insight, and should above all be cautious with the designations.

Heartfelt thanks also for the beautiful picture of the blue morning glory. It appears to be the same that I cultivate year after year in my garden. I did not know that it possesses specific powers; however, that is probably the case with every plant. We do not know the key to most. Besides this, there must be a central viewpoint from which not only the chemistry, the structure, the color, but rather all attributes become significant....

---

An Experiment with Psilocybin

Such theoretical discussions about the magic drugs were supplemented by practical experiments. One such experiment, which served as a comparison between LSD and psilocybin, took place in the spring of 1962. The proper occasion for it presented itself at the home of the Jüngers, in the former head forester's house of Stauffenberg's Castle in Wilflingen. My friends, the pharmacologist Professor Heribert Konzett and the Islamic scholar Dr. Rudolf Gelpke, also took part in this mushroom symposium.

The old chronicles described how the Aztecs drank chocolatl before they ate teonanácatl. Thus Mrs. Liselotte Jünger likewise served us hot chocolate, to set the mood. Then she abandoned the four men to their fate.

We had gathered in a fashionable living room, with a dark wooden ceiling, white tile stove, period furniture, old French engravings on the walls, a gorgeous bouquet of tulips on the table. Ernst Jünger wore a long, broad, dark blue striped kaftan-like garment that he had brought from Egypt; Heribert Konzett was resplendent in a brightly embroidered mandarin gown; Rudolf Gelpke and I had put on housecoats. The everyday reality should be laid aside, along with everyday clothing.

Shortly before sundown we took the drug, not the mushrooms, but rather their active principle, 20 mg psilocybin each. That corresponded to some two-thirds of the very strong dose that was taken by the curandera Maria Sabina in the form of Psilocybe mushrooms.

After an hour I still noticed no effect, while my companions were already very deeply into the trip. I had come with the hope that in the mushroom inebriation I could manage to allow certain images from euphoric moments of my childhood, which remained in my memory as blissful experiences, to come alive: a meadow covered with chrysanthemums lightly stirred by the early summer wind; the rosebush in the evening light after a rain storm; the blue irises hanging over the vineyard wall. Instead of these bright images from my childhood home, strange scenery emerged, when the mushroom factor finally began to act. Half stupefied, I sank deeper, passed through totally deserted cities with a Mexican type of exotic, yet dead splendor. Terrified, I tried to detain myself on the surface, to concentrate alertly on the outer world, on the surroundings. For a time I succeeded. I then observed Ernst Jünger, colossal in the room, pacing back and forth, a powerful, mighty magician. Heribert Konzett in the silky lustrous housecoat seemed to be a dangerous, Chinese clown. Even Rudolf Gelpke appeared sinister to me; long, thin, mysterious.

With the increasing depth of inebriation, everything became yet stranger. I even felt strange to myself. Weird, cold, foolish, deserted, in a dull light, were the places I

traversed when I closed my eyes. Emptied of all meaning, the environment also seemed ghostlike to me whenever I opened my eyes and tried to cling to the outer world. The total emptiness threatened to drag me down into absolute nothingness. I remember how I seized Rudolf Gelpke's arm as he passed by my chair, and held myself to him, in order not to sink into dark nothingness. Fear of death seized me, and illimitable longing to return to the living creation, to the reality of the world of men. After timeless fear I slowly returned to the room . I saw and heard the great magician lecturing uninterruptedly with a clear, loud voice, about Schopenhauer, Kant, Hegel, and speaking about the old Gäa, the beloved little mother. Heribert Konzett and Rudolf Gelpke were already completely on the earth again, while I could only regain my footing with great effort.

For me this entry into the mushroom world had been a test, a confrontation with a dead world and with the void. The experiment had developed differently from what I had expected. Nevertheless, the encounter with the void can also be appraised as a gain. Then the existence of the creation appears so much more wondrous.

Midnight had passed, as we sat together at the table that the mistress of the house had set in the upper story. We celebrated the return with an exquisite repast and with Mozart's music. The conversation, during which we exchanged our experiences, lasted almost until morning.

Ernst Jünger has described how he had experienced this trip, in his book Annähenngen—Drogen und Rausch [Approaches-drugs and inebriation] (published by Ernst Klett Verlag, Stuttgart, 1970), in the section "Ein Pilz-Symposium" [A mushroom symposium]. The following is an extract from the work:

As usual, a half hour or a little more passed in silence. Then came the first signs: the flowers on the table began to flare up and sent out flashes. It was time for leaving work; outside the streets were being cleaned, like on every weekend. The brush strokes invaded the silence painfully. This shuffling and brushing, now and again also a scraping, pounding, rumbling, and hammering, has random causes and is also symptomatic, like one of the signs that announces an illness. Again and again it also plays a role in the history of magic practices.

By this time the mushroom began to act; the spring bouquet glowed darker. That was no natural light. The shadows stirred in the corners, as if they sought form. I became uneasy, even chilled, despite the heat that emanated from the tiles. I stretched myself on the sofa, drew the covers over my head.

Everything became skin and was touched, even the retina-there the contact was light. This light was multicolored; it arranged itself in strings, which gently swung back and forth; in strings of glass beads of oriental doorways. They formed doors, like those one passes through in a dream, curtains of lust and danger. The wind stirred them like a garment. They also fell down from the belts of dancers, opened and closed themselves with the swing of the hips, and from the beads a rippling of the most delicate sounds fluttered to the heightened senses. The chime of the silver rings on the ankles and wrists is already too loud. It smells of sweat, blood, tobacco, chopped horse hairs, cheap rose essence. Who knows what is going on in the stables?

It must be an immense palace, Mauritanian, not a good place. At this ballroom flights of adjoining rooms lead into the lower stratum. And everywhere the curtains with their glitter, their sparkling, radioactive glow. Moreover, the rippling of glassy instruments with their beckoning, their wooing solicitation: "Will you go with me, beautiful boy?" Now it ceased, now it repeated, more importunate, more intrusive, almost already assured of agreement.

Now came forms-historical collages, the vox humana, the call of the cuckoo. Was it the whore of Santa Lucia, who stuck her breasts out of the window? Then the play was ruined. Salome danced; the amber necklace emitted sparks and made the nipples erect. What would one not do for one's Johannes? [Translator's note: "Johannes" here is slang for penis, as in English "Dick" or "Peter."] -damned, that was a disgusting obscenity, which did not come from me, but was whispered through the curtain.

The snakes were dirty, scarcely alive, they wallowed sluggishly over the floor mats. They were garnished with brilliant shards. Others looked up from the floor with red and green eyes. It glistened and whispered, hissed and sparkled like diminutive sickles at the sacred harvest. Then it quieted, and came anew, more faintly, more forward. They had me in their hand. "There we immediately understood ourselves."

Madam came through the curtain: she was busy, passed by me without noticing me. I saw the boots with the red heels. Garters constricted the thick thighs in the middle, the flesh bulged out there. The enormous breasts, the dark delta of the Amazon, parrots, piranhas, semiprecious stones everywhere.

Now she went into the kitchen-or are there still cellars here? The sparkling and whispering, the hissing and twinkling could no longer be differentiated; it seemed to become concentrated, now proudly rejoicing, full of hope.

It became hot and intolerable; I threw the covers off. The room was faintly illuminated; the pharmacologist stood at the window in the white mandarin frock, which had served me shortly before in Rottweil at the carnival. The orientalist sat beside the tile stove; he moaned as if he had a nightmare. I understood; it had been a first round, and it would soon start again. The time was not yet up. I had already seen the beloved little mother under other circumstances. But even excrement is earth, belongs like gold to transformed matter. One must come to terms with it, without getting too close.

These were the earthy mushrooms. More light was hidden in the dark grain that burst from the ear, more yet in the green juice of the succulents on the glowing slopes of Mexico. . . . [Translator's note: Jünger is referring to LSD, a derivative of ergot, and mescaline, derived from the Mexican peyotl cactus.]

The trip had run awry—possibly I should address the mushrooms once more. Yet indeed the whispering returned, the flashing and sparkling—the bait pulled the fish close behind itself. Once the motif is given, then it engraves itself, like on a roller each new beginning, each new revolution repeats the melody. The game did not get beyond this kind of dreariness.

I don't know how often this was repeated, and prefer not to dwell upon it. Also, there are things which one would rather keep to oneself. In any case, midnight was past....

We went upstairs; the table was set. The senses were still heightened and the Doors of Perception were opened. The light undulated from the red wine in the carafe; a froth surged at the brim. We listened to a flute concerto. It had not turned out better for the others: How beautiful, to be back among men." Thus Albert Hofmann.

The orientalist on the other hand had been in Samarkand, where Timur rests in a coffin of nephrite. He had followed the victorious march through cities, whose dowry on entry was a cauldron filled with eyes. There he had long stood before one of the skull pyramids that terrible Timur had erected, and in the multitude of severed heads had perceived even his own. It was encrusted with stones. A light dawned on the pharmacologist when he heard this: Now I know why you were

sitting in the armchair without your head-I was astonished; I knew I wasn't dreaming.

I wonder whether I should not strike out this detail since it borders on the area of ghost stories.

The mushroom substance had carried all four of us off, not into luminous heights, rather into deeper regions. It seems that the psilocybin inebriation is more darkly colored in the majority of cases than the inebriation produced by LSD. The influence of these two active substances is sure to differ from one individual to another. Personally, for me, there was more light in the LSD experiments than in the experiments with the earthy mushroom, just as Ernst Jünger remarks in the preceding report.

---

Another LSD Session

The next and last thrust into the inner universe together with Ernst Jünger, this time again using LSD, led us very far from everyday consciousness. We came close to the ultimate door. Of course this door, according to Ernst Jünger, will in fact only open for us in the great transition from life into the hereafter.

This last joint experiment occurred in February 1970, again at the head forester's house in Wilflingen. In this case there were only the two of us. Ernst Jünger took 0.15 mg LSD, I took 0.10 mg. Ernst Jünger has published without commentary the log book, the notes he made during the experiment, in Approaches, in the section "Nochmals LSD" [LSD once again]. They are scanty and tell the reader little, just like my own records.

The experiment lasted from morning just after breakfast until darkness fell. At the beginning of the trip, we again listened to the concerto for flute and harp by Mozart, which always made me especially happy, but this time, strange to say, seemed to me like the turning of porcelain figures. Then the intoxication led quickly into wordless depths. When I wanted to describe the perplexing alterations of consciousness to Ernst Jünger, no more than two or three words came out, for they sounded so false, so unable to express the experience; they seemed to originate from an infinitely distant world that had become strange; I abandoned the attempt, laughing hopelessly. Obviously, Ernst Jünger had the same experience, yet we did not need speech; a glance sufficed for the deepest understanding. I could, however, put some scraps of sentences on paper, such as at the beginning: "Our boat tosses violently." Later, upon regarding expensively bound books in the library: "Like red-gold pushed from within to without-exuding golden luster." Outside it began to snow. Masked children marched past and carts with carnival revelers passed by in the streets. With a glance through the window into the garden, in which snow patches lay, many-colored masks appeared over the high walls bordering it, embedded in an infinitely joyful shade of blue: "A Breughel garden—I live with and in the objects." Later: "At present—no connection with the everyday world." Toward the end, deep, comforting insight expressed: "Hitherto confirmed on my path." This time LSD had led to a blessed approach.

-----

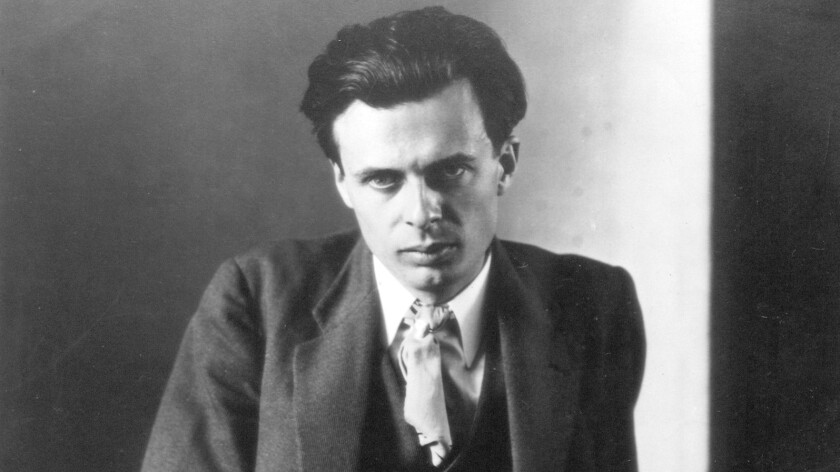

Meeting with Aldous Huxley

In the mid-1950s, two books by Aldous Huxley appeared, The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell, dealing with inebriated states produced by hallucinogenic drugs. The alterations of sensory perceptions and consciousness, which the author experienced in a self-experiment with mescaline, are skillfully described in these books. The mescaline experiment was a visionary experience for Huxley. He saw objects in a new light; they disclosed their inherent, deep, timeless existence, which remains hidden from everyday sight.

These two books contained fundamental observations on the essence of visionary experience and about the significance of this manner of comprehending the world—in cultural history, in the creation of myths, in the origin of religions, and in the creative process out of which works of art arise. Huxley saw the value of hallucinogenic drugs in that they give people who lack the gift of spontaneous visionary perception belonging to mystics, saints, and great artists, the potential to experience this extraordinary state of consciousness, and thereby to attain insight into the spiritual world of these great creators. Hallucinogens could lead to a deepened understanding of religious and mystical content, and to a new and fresh experience of the great works of art. For Huxley these drugs were keys capable of opening new doors of perception; chemical keys, in addition to other proven but laborious " door openers" to the visionary world like meditation, isolation, and fasting, or like certain yoga practices.

At the time I already knew the earlier work of this great writer and thinker, books that meant much to me, like Point Counter Point, Brave New World, After Many a Summer, Eyeless in Gaza, and a few others. In The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell, Huxley's newly-published works, I found a meaningful exposition of the experience induced by hallucinogenic drugs, and I thereby gained a deepened insight into my own LSD experiments.

I was therefore delighted when I received a telephone call from Aldous Huxley in the laboratory one morning in August 1961. He was passing through Zurich with his wife. He invited me and my wife to lunch in the Hotel Sonnenberg.

A gentleman with a yellow freesia in his buttonhole, a tall and noble appearance, who exuded kindness—this is the image I retained from this first meeting with Aldous Huxley. The table conversation revolved mainly around the problem of magic drugs. Both Huxley and his wife, Laura Archera Huxley, had also experimented with LSD and psilocybin. Huxley would have preferred not to designate these two substances and mescaline as "drugs," because in English usage, as also by the way with Droge in German, that word has a pejorative connotation, and because it was important to differentiate the hallucinogens from the other drugs, even linguistically. He believed in the great importance of agents producing visionary experience in the modern phase of human evolution.

He considered experiments under laboratory conditions to be insignificant, since in the extraordinarily intensified susceptibility and sensitivity to external impressions, the surroundings are of decisive importance. He recommended to my wife, when we spoke of her native place in the mountains, that she take LSD in an alpine meadow and then look into the blue cup of a gentian flower, to behold the wonder of creation.

As we parted, Aldous Huxley gave me, as a remembrance of this meeting, a tape recording of his lecture "Visionary Experience," which he had delivered the week before at an international congress on applied psychology in Copenhagen. In this lecture, Aldous Huxley spoke about the meaning and essence of visionary experience and compared this type of world view to the verbal and intellectual comprehension of reality as its essential complement.

In the following year, the newest and last book by Aldous Huxley appeared, the novel Island. This story, set on the utopian island Pala, is an attempt to blend the achievements of natural science and technical civilization with the wisdom of Eastern thought, to achieve a new culture in which rationalism and mysticism are fruitfully united. The moksha medicine, a magical drug prepared from a mushroom, plays a significant role in the life of the population of Pala (moksha is Sanskrit for "release," "liberation"). The drug could be used only in critical periods of life. The young men on Pala received it in initiation rites, it is dispensed to the protagonist of the novel during a life crisis, in the scope of a psychotherapeutic dialogue with a spiritual friend, and it helps the dying to relinquish the mortal body, in the transition to another existence.

In our conversation in Zurich, I had already learned from Aldous Huxley that he would again treat the problem of psychedelic drugs in his forthcoming novel. Now he sent me a copy of Island, inscribed "To Dr. Albert Hofmann, the original discoverer of the moksha medicine, from Aldous Huxley."

The hopes that Aldous Huxley placed in psychedelic drugs as a means of evoking visionary experience, and the uses of these substances in everyday life, are subjects of a letter of 29 February 1962, in which he wrote me: . . . I have good hopes that this and similar work will result in the development of a real Natural History of visionary experience, in all its variations, determined by differences of physique, temperament and profession, and at the same time of a technique of Applied Mysticism—a technique for helping individuals to get the most out of their transcendental experience and to make use of the insights from the "Other World" in the affairs of "This World." Meister Eckhart wrote that "what is taken in by contemplation must be given out in love." Essentially this is what must be developed—the art of giving out in love and intelligence what is taken in from vision and the experience of self-transcendence and solidarity with the Universe....

Aldous Huxley and I were together often at the annual convention of the World Academy of Arts and Sciences (WAAS) in Stockholm during late summer 1963. His suggestions and contributions to discussions at the sessions of the academy, through their form and importance, had a great influence on the proceedings.

WAAS had been established in order to allow the most competent specialists to consider world problems in a forum free of ideological and religious restrictions and from an international viewpoint encompassing the whole world. The results: proposals, and thoughts in the form of appropriate publications, were to be placed at the disposal of the responsible governments and executive organizations.

The 1963 meeting of WAAS had dealt with the population explosion and the raw material reserves and food resources of the earth. The corresponding studies and proposals were collected in Volume II of WAAS under the title The Population Crisis and the Use of World Resources. A decade before birth control, environmental protection, and the energy crisis became catchwords, these world problems were examined there from the most serious point of view, and proposals for their solution were made to governments and responsible organizations. The catastrophic events since that time in the aforementioned fields makes evident the tragic discrepancy between recognition, desire, and feasibility.

Aldous Huxley made the proposal, as a continuation and complement of the theme "World Resources" at the Stockholm convention, to address the problem "Human Resources," the exploration and application of capabilities hidden in humans yet unused. A human race with more highly developed spiritual capacities, with expanded consciousness of the depth and the incomprehensible wonder of being, would also have greater understanding of and better consideration for the biological and material foundations of life on this earth. Above all, for Western people with their hypertrophied rationality, the development and expansion of a direct, emotional experience of reality, unobstructed by words and concepts, would be of evolutionary significance. Huxley considered psychedelic drugs to be one means to achieve education in this direction. The psychiatrist Dr. Humphry Osmond, likewise participating in the congress, who had created the term psychedelic (mind-expanding), assisted him with a report about significant possibilities of the use of hallucinogens.

The convention in Stockholm in 1963 was my last meeting with Aldous Huxley. His physical appearance was already marked by a severe illness; his intellectual personage, however, still bore the undiminished signs of a comprehensive knowledge of the heights and depths of the inner and outer world of man, which he had displayed with so much genius, love, goodness, and humor in his literary work.

Aldous Huxley died on 22 November of the same year, on the same day President Kennedy was assassinated. From Laura Huxley I obtained a copy of her letter to Julian and Juliette Huxley, in which she reported to her brother- and sister-in-law about her husband's last day. The doctors had prepared her for a dramatic end, because the terminal phase of cancer of the throat, from which Aldous Huxley suffered, is usually accompanied by convulsions and choking fits. He died serenely and peacefully, however.

In the morning, when he was already so weak that he could no longer speak, he had written on a sheet of paper: "LSD—try it—intramuscular—100 mmg." Mrs. Huxley understood what was meant by this, and ignoring the misgivings of the attending physician, she gave him, with her own hand, the desired injection-she let him have the moksha medicine.

-----

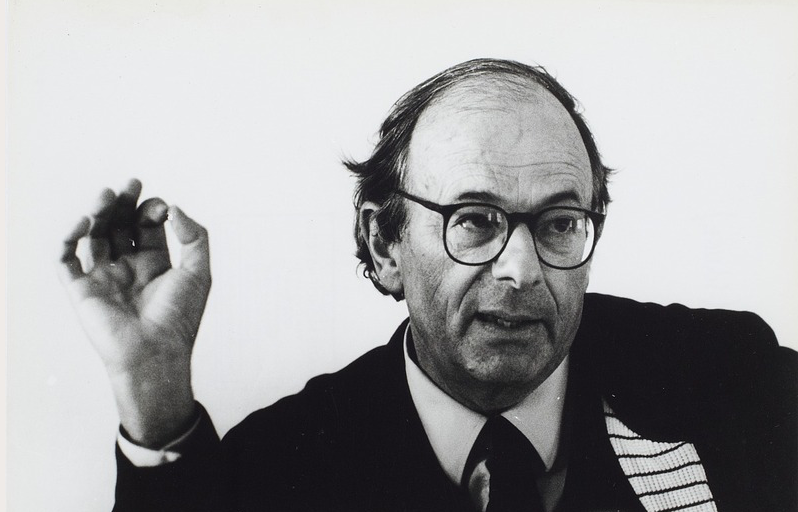

Correspondence with the Poet-Physician Walter Vogt

My friendship with the physician, psychiatrist, and writer Walter Vogt, M.D., is also among the personal contacts that I owe to LSD. As the following extract from our correspondence shows, it was less the medicinal aspects of LSD, important to the physician, than the consciousness-altering effects on the depth of the psyche, of interest to the writer, that constituted the theme of our correspondence.

Muri/Bern, 22 November 1970

Dear Mr. Hofmann,

Last night I dreamed that I was invited to tea in a cafe by a friendly family in Rome. This family also knew the pope, and so the pope sat at—the same table to tea with us. He was all in white and also wore a white miter. He sat there so handsome and was silent.

And today I suddenly had the idea of sending you my Vogel auf dem Tisch [Bird on the table—as a visiting card if you so wish—a book that remained a little apocryphal, which upon reflection I do not regret, although the Italian translator is firmly convinced that is my best. (Ah yes, the pope is also an Italian. So it goes. ...)

Possibly this little work will interest you. It was written in 1966 by an author who at that time still had not had any shred of experience with psychedelic substances and who read the reports about medicinal experiments with these drugs devoid of understanding. However, little has changed since, except that now the misgiving comes from the other side.

I suppose that your discovery has caused a hiatus (not directly a Saul-to-Paul conversion as Roland Fischer says...) in my work (also a large word) - and indeed, that which I have written since has become rather realistic or at least less expressive. In any case I could not have brought off the cool realism of my TV piece "Spiele der Macht" [Games of power] without it. The different drafts attest it, in case they are still lying around somewhere.

Should you have interest and time for a meeting, it would delight me very much to visit you sometime for a conversation.

W. V.

---

Burg, i.L. 28 November 1970

Dear Mr. Vogt,

If the bird that alighted on my table was able to find its way to me, this is one more debt I owe to the magical effect of LSD. I could soon write a book about all of the results that derive from that experiment in 1943....

A. H.

---

Muri/Bern, 13 March 1971

Dear Mr. Hofmann,

Enclosed is a critique of Jünger's Annahenngen [Approaches], from the daily paper, that will presumably interest you....

It seems to me that to hallucinate—to dream—to write, stands at all times in contrast to everyday consciousness, and their functions are complementary. Here I can naturally speak only for myself. This could be different with others—it is also truly difficult to speak with others about such things, because people often speak altogether different languages....

However, since you are now gathering autographs, and do me the honor of incorporating some of my letters in your collection, I enclose for you the manuscript of my "testament"—in which your discovery plays a role as "the only joyous invention of the twentieth century...."

W. V. dr. walter vogts most recent testament 1969

I wish to have no special funeral

only expensive and obscene orchids

innumerable little birds with gay names

no naked dancers

but

psychedelic garments

loudspeaker in every corner and

nothing but the latest beatles record [Abbey Road]

one hundred thousand million times

and

do what you like ["Blind Faith"]

on an endless tape

nothing more

than a popular Christ with a halo of genuine gold

and a beloved mourning congregation

that pumped themselves full with LSD

till they go to heaven [From Abbey Road, side two]

one two three four five six seven

possibly we will encounter one another there

most cordially dedicated

to Dr. Albert Hofmann

Beginning of Spring 1971

---

urg i.L., 29 March 1971

Dear Mr. Vogt,

You have again presented me with a lovely letter and a very valuable autograph, the testament 1969....

Very remarkable dreams in recent times induce me to test a connection between the composition (chemical) of the evening meal and the quality of dreams. Yes, LSD is also something that one eats....

A. H.

---

Muri/Bern, 5 September 1971

Dear Mr. Hofmann,

Over the weekend at Murtensee [On that Sunday, I (A. H.) hovered over the Murtensee in the balloon of my friend E. I., who had taken me along as passenger.] I often thought of you—a most radiant autumn day. Yesterday, Saturday, thanks to one tablet of aspirin (on account of a headache or mild flu), I experienced a very comical flashback, like with mescaline (of which I have had only a little, exactly once)....

I have read a delightful essay by Wasson about mushrooms; he divides mankind into mycophobes and mycophiles.... Lovely fly agarics must now be growing in the forest near you. Sometime shouldn't we sample some?

W. V.

---

Muri/Bern, 7 September 1971

Dear Mr. Hofmann,

Now I feel I must write briefly to tell you what I have done outside in the sun, on the dock under your balloon: I finally wrote some notes about our visit in Villars-sur-Ollons (with Dr. Leary), then a hippie-bark went by on the lake, self-made like from a Fellini film, which I sketched, and over and above it I drew your balloon.

W. V.

---

Burg i.L., 15 April 1972

Dear Mr. Vogt,

Your television play "Spiele der Macht" [Games of power] has impressed me extraordinarily.

I congratulate you on this magnificent piece, which allows mental cruelty to become conscious, and therefore also acts in its way as "consciousness- expanding", and can thereby prove itself therapeutic in a higher sense, like ancient tragedy.

A. H.

---

Burg i.L., 19 May 1973

Dear Mr. Vogt,

Now I have already read your lay sermon three times, the description and interpretation of your Sinai Trip. [Walter Vogt: Mein Sinai Trip. Eine Laienpredigt [My Sinai trip: A lay sermon] (Verlag der Arche, Zurich, 1972). This publication contains the text of a lay sermon that Walter Vogt gave on 14 November 1971 on the invitation of Parson Christoph Mohl, in the Protestant church of Vaduz (Lichtenstein), in the course of a series of sermons by writers, and in addition contains an afterword by the author and by the inviting parson. It involves the description and interpretation of an ecstatic-religious experience evoked by LSD, that the author is able to "place in a distant, if you will superficial, analogy to the great Sinai Trip of Moses." It is not only the "patriarchal atmosphere" that is to be traced out of these descriptions, that constitutes this analogy; there are deeper references, which are more to be read between the lines of this text.] Was it really an LSD trip?... It was a courageous deed, to choose such a notorious event as a drug experience as the theme of a sermon, even a lay sermon. But the questions raised by hallucinogenic drugs do actually belong in the church—in a prominent place in the church, for they are sacred drugs (peyotl, teonanacatl, ololiuhqui, with which LSD is mostly closely related by chemical structure and activity).

I can fully agree with what you say in your introduction about the modern ecclesiastical religiosity: the three sanctioned states of consciousness (the waking condition of uninterrupted work and performance of duty, alcoholic intoxication, and sleep), the distinction between two phases of psychedelic inebriation (the first phase, the peak of the trip, in which the cosmic relationship is experienced, or the submersion into one's own body, in which everything that is, is within; and the second phase, characterized as the phase of enhanced comprehension of symbols), and the allusion to the candor that hallucinogens bring about in consciousness states. These are all observations that are of fundamental importance in the judgment of hallucinogenic inebriation.

The most worthwhile spiritual benefit from LSD experiments was the experience of the inextricable intertwining of the physical and spiritual. "Christ in matter" (Teilhard de Chardin). Did the insight first come to you also through your drug experiences, that we must descend "into the flesh, which we are," in order to get new prophesies?

A criticism of your sermon: you allow the "deepest experience that there is"—"The kingdom of heaven is within you"—to be uttered by Timothy Leary. This sentence, quoted without the indication of its true source, could be interpreted as ignorance of one, or rather the principal truth of Christian belief.

One of your statements deserves universal recognition: "There is no non-ecstatic religious experience."...

Next Monday evening I shall be interviewed on Swiss television (about LSD and the Mexican magic drugs, on the program "At First Hand"). I am curious about the sort of questions that will be asked...

A. H.

---

Muri/Bern, 24 May 1973

Dear Mr. Hofmann,

Of course it was LSD—only I did not want to write about it explicitly, I really do not know just why myself.... The great emphasis I placed on the good Leary, who now seems to me to be somewhat flipped out, as the prime witness, can indeed only be explained by the special context of the talk or sermon.

I must admit that the perception that we must descend "into the flesh, which we are" actually first came to me with LSD. I still ruminate on it, possibly it even came "too late" for me in fact, although more and more I advocate your opinion that LSD should be taboo for youth (taboo, not forbidden, that is the difference...).

The sentence that you like, "there is no nonecstatic religious experience," was apparently not liked so much by others—for example, by my (almost only) literary friend and minister-lyric poet Kurt Marti.... But in any case, we are practically never of the same opinion about anything, and notwithstanding, we constitute when we occasionally communicate by phone and arrange little activities together, the smallest minimafia of Switzerland.

W. V.

---

Burg i.L., 13 April 1974

Dear Mr. Vogt,

Full of suspense, we watched your TV play "Pilate before the Silent Christ" yesterday evening.

... as a representation of the fundamental man-God relationship: man, who comes to God with his most difficult questions, which finally he must answer himself, because God is silent. He does not answer them with words. The answers are contained in the book of his creation (to which the questioning man himself belongs). True natural science deciphering of this text.

A. H.

---

Muri/Bern, 11 May 1974

Dear Mr. Hofmann,

I have composed a "poem" in half twilight, that I dare to send to you. At first I wanted to send it to Leary, but this would make no sense.

Leary in jail

Gelpke is dead

Treatment in the asylum

is this your psychedelic

revolution?

Had we taken seriously something

with which one only ought to play

or

vice-versa...

W. V.

https://maps.org/images/pdf/books/lsdmyproblemchild.pdf