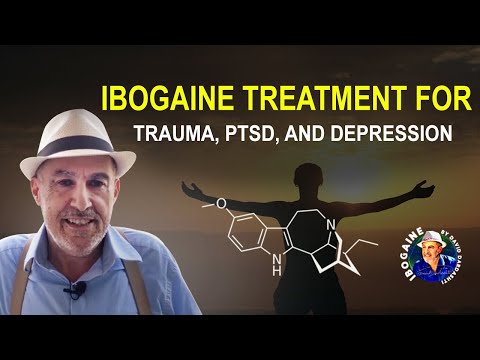

Dr. Daniel Sumrok

Is Childhood Trauma the Root Cause of Addiction?*

by Jane Ellen

"

When you’re a child, you can’t control the people who abuse and assault you, who create hostile environments. If a child can’t control their environment, because of these things they grow up thinking they’re bad, different, horrible people. This new approach helps them feel like they’re not drowning anymore."

Introducing Dr. Daniel Sumrok, director of the Center for Addiction Sciences at University of Tennessee’s College of Medicine. The center is the first to receive the Center of Excellence designation from the Addiction Medicine Foundation, a national organization that accredits physician training in addiction medicine. Sumrok is also one of the first 106 physicians in the U.S. to become board-certified in addiction medicine by the American Board of Medical Specialties.

"Addiction shouldn’t be called “addiction,”it should be called “ritualized compulsive comfort-seeking,” says Dr. Sumrok.

"Ritualized compulsive comfort-seeking is a normal response to the adversity experienced in childhood, just like bleeding is a normal response to being stabbed."

"The solution to changing ritualized compulsive comfort-seeking behavior to address a person’s adverse childhood experiences (ACE) individually and in group therapy; treat people with respect; provide medication assistance in the form of buprenorphine, an opioid used to treat opioid addiction; and help them find a ritualized compulsive comfort-seeking behavior that won’t kill them or put them in jail. My patients seem to respond really well to this,” he says.

Sumrok, a family physician and former U.S. Army Green Beret who’s served the rural area around McKenzie, TN, for the last 28 years, combines the latest science of addiction and applies it to his patients, most of whom are addicted to opioids. He sees them in the center’s two outpatient clinics: his clinic, which the Center for Addiction Science ha taken over as its rural clinic, and another that opened recently in downtown Memphis.

Since he first sat down in the early 1980s to write a research paper (“Public Health Legacy of the Vietnam War: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Implications for Appalachians”) to describe the symptoms of the newly named post-traumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans –

“problems with the law, having trouble sleeping, anxiety, divorce, sleep troubles, substance use disorders, depression, anxiety, cognitive and chronic pain issues” — Sumrok has pieced together the ingredients for a revolutionary approach to addiction. It’s an approach that’s advocated by many of the leading thinkers in addiction and trauma, including Drs. Gabor Maté, Lance Dodes and Bessel van der Kolk. Surprisingly, it’s a fairly simple formula:

Treat people with respect instead of blaming or shaming them. Listen intently to what they have to say. Integrate the healing traditions of the culture in which they live. Use prescription drugs, if necessary. And integrate adverse childhood experiences science: ACE.

ACE understanding changes practice

Learning about ACE more than two years ago was a big turning point for his understanding of addictions, explains Sumrok.

“I was working in an eating disorders clinic and someone told me ‘90 percent of these folks have sexual trauma’. I remember thinking: That can’t be right. But that was exactly right. Since I’ve learned about ACE, I talk about it every day.”

He also practices it every day, by integrating ACE assessments for all patients in his clinics. He currently has about 200 patients who are addicted, most to opioids (heroin and prescription pain relievers, including oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine, morphine, and fentanyl).

“I’ve seen about 1,200 patients who are addicted,” he says.

“Of those, more than 1,100 have an ACE score of 3 or more.”

Sumrok knows that score says a lot about their health and ability to cope: ACE comes from the CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE Study), groundbreaking research that looked at how 10 types of childhood trauma affect long-term health. They include: physical, emotional and sexual abuse; physical and emotional neglect; living with a family member who’s addicted to alcohol or other substances, or who’s depressed or has other mental illnesses; experiencing parental divorce or separation; having a family member who’s incarcerated, and witnessing a mother being abused. Subsequent ACE surveys include racism, witnessing violence outside the home, bullying, losing a parent to deportation, living in an unsafe neighborhood, and involvement with the foster care system. Other types of childhood adversity can also include being homeless, living in a war zone, being an immigrant, moving many times, witnessing a sibling being abused, witnessing a father or other caregiver or extended family member being abused, involvement with the criminal justice system, attending a school that enforces a zero-tolerance discipline policy, etc.

The ACE Study is one of five parts of ACE science, which also includes how toxic stress from ACE damage children’s developing brains; how toxic stress from ACE affects health; and how it can affect our genes and be passed from one generation to another (epigenetics); and resilience research, which shows the brain is plastic and the body wants to heal. Resilience research focuses on what happens when individuals, organizations and systems integrate trauma-informed and resilience-building practices, for example in education and in the family court system.

The ACE Study found that the higher someone’s ACE score – the more types of childhood adversity a person experienced – the higher their risk of chronic disease, mental illness, violence, being a victim of violence and a bunch of other consequences. The study found that most people (64 ercent have at least one ACE; 12% of the population has an ACE score of 4. Having an ACE score of 4 nearly doubles the risk of heart disease and cancer. It increases the likelihood of becoming an alcoholic by 700 percent and the risk of attempted suicide by 1200 percent.

(For more information, go to ACE Science 101. To calculate your ACE and resilience scores, go to: Got Your ACE Score?)

High ACE scores also relate to addiction: Compared with people who have zero ACE, people with ACE scores are two to four times more likely to use alcohol or other drugs and to start using drugs at an earlier age. People with an ACE score of 5 or higher are seven to 10 times more likely to use illegal drugs, to report addiction and to inject illegal drugs.

The ACE Study also found that it didn’t matter what the types of ACE were. An ACE score of 4 that includes divorce, physical abuse, an incarcerated family member and a depressed family member has the same statistical health consequences as an ACE score of 4 that includes living with an alcoholic, verbal abuse, emotional neglect and physical neglect.

Subsequent research on the link between childhood adversity and addiction corroborates the findings from the ACE Study, including studies that have found that people who’ve experienced childhood trauma have more chronic pain and use more prescription drugs; people who experienced five or more traumatic events are three times more likely to misuse prescription pain medications.

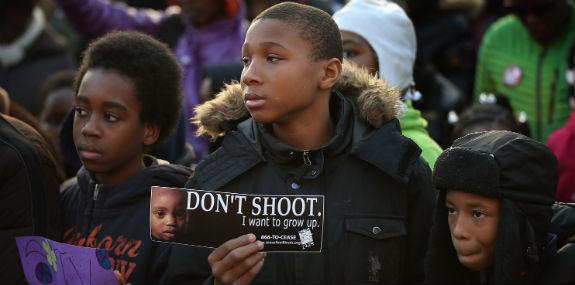

Dr. Dan Sumrok with group therapy members at McKenzie, TN, clinic.

“ACE doesn’t just predict substance abuse disorders,” says Sumrok.

“Major chronic diseases are so often linked to substance abuse, this is too big to ignore.”

Whether you’re talking about obesity, addiction to cigarettes, alcohol or opioids, the cause is the same, he says:

“It’s the trauma of childhood that causes neurobiological changes.” And the symptoms he saw 40 years ago in soldiers returning from Vietnam are the same in the people he sees today who are addicted to opioids or other substances or behaviors that help them cope with the anxiety, depression, hopelessness, fear, anger, and/or frustration that continues to be generated from the trauma they experienced as children.

Learning about ACE helped him understand that the original definition of PTSD, which many people still cling to, is not accurate. In the 1980s, PTSD was defined as a result of trauma that was outside the realm of normal experience.

“That was just wrong,” says Sumrok.

“Divorce, living with depressed or addicted family members are very common events for kids. My efforts are around helping people to see the connections, and that their experiences are predictable and normal. And the longer the experiences last, the bigger the effect.”

He also says,

“Drop the ‘D’, because PTSD is not a disorder.” It’s what he learned from van der Kolk, who wrote The Body Keeps the Score.

“Bessel says we’ve named this thing wrong. Post-traumatic stress is a brain adaptation. It’s not an imagined fear. If one of your feet was bitten off by a lion, you’re going to be on guard for lions,” explains Sumrok.

“Hypervigilance is not an imagined fear, if you’ve had one foot bitten off by a lion. It’s a real fear, and you’re going to be on the lookout for that lion. I tell my patients that they’ve had real trauma that’s not imagined. They’re not crazy.”

Patients who learn about their ACE understand that they can heal

This is what happens when a person sees Sumrok for the first time: They fill out the 10-question ACE survey (Got Your ACE Score?) in the waiting room.

“Then when I see them, I go through each question and ask them again,” says Sumrok, who also does a normal physical exam.

“Frequently, there’s a difference between the two. For example, this morning, I saw a woman and she reported an ACE score of 1 on the survey. Then, when I asked her the questions, she reported nine out of 10.”

That’s just how I grew up, she told Sumrok. She didn’t think being beaten, humiliated or seeing her mother smoking crack every day was harmful or unusual, especially since most kids she knew were experiencing the same thing.

Sumrok normalizes their addiction, which he explains is the coping behavior they adopted because they weren’t provided with a healthy alternative when they were young. He explains the science of adverse childhood experiences to them, and how their addictions are a normal – and a predictable – result of their childhood trauma. He explains

"what happens in the brain when they experience toxic stress, how their amygdala is their emotional fuse box. How the thinking part of their brain didn’t develop the way it should have. How it goes offline at the first sign of danger, even if they’re not connecting the trigger with the experience. Drugs like Zoloft don’t really help much," he tells them.

"Zoloft and other anti-depressants don’t remove the memory triggered by the odor of after shave that was worn by your uncle who sexually abused you when you were eight, or the memory triggered by a voice that sounds just like your mother who used to beat you with a belt, or by a face of a man who looks like your father who used to scream at you about how worthless you were…" The examples are infinite. That’s why van der Kolk says,

“’The body keeps the score’,” Sumrok says.

“After I explain all this to them, many of them stare at me and say: ‘You mean I’m not crazy?’” says Sumrok.

“I tell them, ‘No, you’re not crazy’.” Sometimes he yells out the door to his nurse:

"Patsy! Where’s my not-crazy stamp? I need to stamp this person’s chart.”

For people who are addicted to opioids, he prescribes buprenorphine (one of the brand names: Suboxone), which helps them to withdraw from opioids and to keep their job, or return to work. For most people, the drug is less addictive than other opioids. Sometimes if people are young, healthy and haven’t been addicted long, they can withdraw from opioids without buprenorphine.

“There’s no buzz associated with buprenorphine,” says Sumrok.

“They can concentrate and think. Once they’re free of the continuous distraction of the acquisition and use of substances, they become pretty valuable employees.”

For people who are addicted to alcohol, he prescribes naltrexone (one of the brand names: Revia), because alcoholics have a high risk of death if they aren’t provided medication. And in this current national attention on opioids, Sumrok is careful to point out that although 33,000 people died from opioid overdose in 2015, 88,000 people die annually from alcohol-related causes, and 480,000 from cigarette smoking. The complicating factor — and why policies don’t work when they chase the eradication of one drug, only to focus on eradicating the next popular drug of choice for

“ritualized compulsive comfort-seeking” — is that many people use opioids and alcohol and cigarettes. And if they receive no help to get at why they’re using legal or illegal substances, they will move on to another, more easily accessible drug when the current drug they’re using becomes more difficult to find.

All patients sign a contract agreeing that they won’t drink alcohol or take other drugs.

“We don’t mess around with that,” says Sumrok.

“We can’t deal with them being deceptive, because if they drink or do other drugs, it can kill them. If their drug screens aren’t consistent, we ask them to find another doctor. Just about everybody stays," he says.

They also participate in group therapy. For physicians who prescribe buprenorphine, it’s now required, but Sumrok had seen the research about the effectiveness of group therapy, and had started 12-step groups for his patients about 10 years ago. Talking with others who have the same experiences helps each person normalize their own experiences. Sumrok and the others in the group help each other find

“ritualized compulsive comfort-seeking behaviors” that won’t kill them or put them in jail, such as coaching their kid’s soccer team or volunteering at a food bank. Sumrok encourages them to integrate other rituals into their lives, such as walking 30 minutes a day or other exercise, joining a 12-step group or finding a path to encourage a spiritual awakening.

“Six months into this,” says Sumrok,

“they start saying things like, ‘My wife and I are back together,

’ or they’re hanging out with their kids. It’s pretty cool to see how people get their lives back. My favorite word is ‘normal’. When they tell me they feel normal, I know they’re doing okay.”

So, how long does it take before they’re cured?

“How long should you take insulin if you have diabetes?” responds Sumrok, making the point that this is a chronic disease, that people should be in treatment for as long as it is necessary, and that some may relapse. His goal is for them to not have to use buprenorphine, but he knows that because of the number and duration of their ACE, and the paucity of resilience factors provided to them when they were children, many will need continual support. He helps them learn how to integrate that support into their lives.

“When a diabetes patient comes in with a blood sugar level of 300, we don’t say: ‘Give me back that insulin.’

We intensify the treatment to get them back in balance,” explains Sumrok.

“Only in addictions do we shame people. We tell them they can’t be part of this recovery anymore. We create a teeny hoop that’s called abstinence, and not too many people can jump through that hoop. If every time we saw a diabetic, we told them that their kidneys were going to fail, they would be blind and we would amputate their extremities, there wouldn’t be many diabetics who got help. I have patients who drop out, and then return a couple of months later, and say, ‘Doc, Christmas came, I saw some of my buddies, and I started using again.’

I tell them, ‘Come on in. Let’s work with you.’

And I remind myself that I’m not saving souls, I’m saving their asses. It’s about getting them so they can function at work, at home, at play. It’s not about making them perfect human beings."

“It has been abundantly clear to me and reinforced over a 40-year career,” continues Sumrok,

“that patients desire, and respond better to, sensitive and informed care. From the Navajo Nation, to Appalachia, to Memphis, to the mountains of Honduras, to the jungles of Amazonia - people regard respect as the sine qua non of quality care.”

Stories AND data drive solutions

Although Sumrok thinks his approach benefits his patients, he knows he needs data to prove it. When he saw a recent study that said 43% of people on buprenorphine were using other opioids, he did his own analysis of a sample of his patients, and found that only 8% were using other opioids. After tracking down those who were, most had good reasons, such as a man whose arm and shoulder were in a new cast after surgery repairing an injury, and he was taking a narcotic. Only one did not, and when shown his drug test, he said, "

'You know what? I slipped.' He talked about it in group," says Sumrok, and everyone in his group hovered around him to make sure he’d continue the program.

Dr. Karen Derefinko

Because Sumrok has kept fastidious records of the patients who have done their ACE scores, Dr. Karen Derefinko, a clinical psychologist and assistant professor in the Department of Preventive Medicine at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, is starting a research project to examine all 1,200 records in Sumrok’s clinic in McKenzie to look at the relationship between people’s ACE scores and their adherence to treatment and their relapses.

“We think that people with high ACE scores are likely to have more relapses,” she says.

“And that may be because people with higher scores have fewer resources and more difficulty associated with adhering to their treatment plans.”

She and her research assistant will de-identify the records, so that all information is anonymous, and then collect the data. Once that data is analyzed — probably within two months — Derefinko and her assistant will conduct focus groups of some of Sumrok’s patients. She’s already been sitting in some of the groups.

“Dan encourages this participatory nature of his groups,” she says.

“People are very willing to talk. After the group sessions, they’re often not done talking about why they came to Sumrok and why other programs didn’t work for them.”

Through the records and the focus groups, Derefinko hopes to identify barriers to care, which include basics such as how people can find good care easily (most of Sumrok’s patients find out about him through word of mouth), being wary of the treatment because it isn’t explained to them, or — what Sumrok hears a lot — being judged or talked down to instead of given understanding and respect.

“In Shelby County, people complain about barriers to care, which many people think is because of economics,” she says.

“But it may not be just economics that is keeping people from accessing treatment; it may be more about being judged, and not knowing what the treatment looks like.”

Being treated with respect builds trust, trust builds health

One of Sumrok’s patients – I’ll call him John, which is not his real name – has been driving 140 miles from Southeast Missouri to see Sumrok for the last five years. He began using drugs off and on during his 20s. When he was in his 30s, he injured his back, was sent to a worker’s comp physician, who prescribed stronger doses of pain killers until his back stopped hurting.

“I was taking pain pills like candy,” says the 46-year-old, who is married and has a son.

“All of a sudden, the pills are gone, and you’re very sick, and I start looking for them everywhere – on the street, taking them from family members without asking – just to keep me from getting sick. I thought I had to have them to function. If I didn’t have six or seven pain pills, I wasn’t going to be able to get out of bed. If I didn’t get them, I’d be sick, puking… I’d do almost anything to have those pills.”

After he spent his and his wife’s life savings, and the money they’d put away to buy a home, and his retirement fund from a previous job; after he saw friends die from overdosing; and after he realized that he was risking losing his wife and son, he told his wife he needed help, and they found Sumrok.

“It’s been a miracle, for sure,” says John. As the Suboxone took effect,

“after two or three weeks, I began to feel normal again.”

About two years ago, Sumrok asked him to fill out the ACE survey.

“It really did make a difference,” says John. He had never connected experiences in his childhood with using drugs as an adult.

“When I was just a baby,” recalls John,

“my grandpa took me from my mother, and told my parents: ‘When you guys are stable, I’ll let you have him back.’

Up until I was 10 or 11, I called them ‘Mom’ and ‘Dad’.’” His older sisters were sent to live with his other set of grandparents. He didn’t live with his parents again until he was 15 years old. His sisters were adults and out on their own by then.

Until he did the ACE survey and talked with Sumrok about his childhood, it didn’t dawn on him that losing his mother, father and his sisters at a young age could have affected him in ways he didn’t realize.

“I knew I was loved by my grandfather and grandmother, but being a young kid and seeing other kids going out with their parents was frustrating,” he says.

“I lived with old people who never left the house, while my parents were out running around. I maybe thought my mom and dad didn’t care about me enough to change. I might have always felt like I wasn’t important enough to my mom and dad for them to change the way they were living and acting.”

But now he has a better understanding of what it was like to be a 19-year-old in the late 1960s and involved in the drug and party scene then, as his parents were. He understands them better, and why they weren’t able to care for him. He and his family members have

“had our discussions,” says John.

“My family life is a whole lot better. I didn’t have relationships with my parents or sisters. We only live seven miles apart, and I barely saw them twice a year, if that. But now I have my wife back. I’ve got my son back. And I see my parents and sisters all the time. We’re a tight-knit family.” He’s also able to hold a job, and is a reliable employee.

John sees Sumrok once a month now. He participates in group therapy, where they can safely talk about their ACE scores without having to get into specifics. He checks in with Sumrok, who renews his prescription.

“I like group therapy with Dr. Sumrok,” says John.

“He talks to us with respect. We feel very comfortable with him. Dr. Sumrok never lies. I trust him fully. And he trusts me. It took five or six months to build that trust. The more I met with him, the more I realized that he was really concerned about me. He wants to help people. Let him train more doctors in the procedures he uses. You can’t treat people like they’re nobodies.”

A 29-year-old patient, who chose to be called “Mr. Big” since I’m not using his real name, has been seeing Sumrok for the last six months. He had been in a methadone treatment program, and found Sumrok after he couldn’t pay for treatment any longer. Sumrok was the only physician who would take his insurance. Mr. Big filled out the ACE survey in the waiting room, but reported his score as a two. Then Sumrok went through the survey with him, and Mr. Big’s score climbed to an 8.

“It does help me understand my addiction better,” says Mr. Big, who is a single father of two children, five and six years old.

“For one, my trauma in my childhood was very dramatic. I thought everyone’s parents did what they were doing. I could see why I related to narcotics and stuff. It was the only place I had to turn. I started taking opiates when I was 11 or 12 years old. I was playing football, and broke my ankle. They gave me painkillers that made me feel like Superman. I couldn’t get enough, because I wasn’t feeling like Superman without it.”

The Suboxone helps him feel

“normal — probably the way everybody else feels,” says Mr. Big.

“Nothing I took ever gave me that feeling before. I’m a better person, father, and a better brother” to his sister, whom he convinced to also get help from Sumrok.

The first time he went for help, to a methadone clinic, he didn’t like it for two reasons: Methadone made him nod off or feel high, and the people at the clinic treated him as if he was a number, or just there for the drugs.

“That’s just unprofessional, in my opinion,” he says.

“Sumrok actually sits down and talks to you like a human being.”

Mr. Big wants to work with Sumrok to develop a

'game plan so that I can live without my medicine,' he says. He just wants to live a normal life. What does a normal life mean?

“It means that I’m home overnight with my children,” he says.

“I don’t have to rob, lie, steal, or cheat to find drugs. I can fit in with society and not be high off my mind. I can wake up every day and do stuff. My children — they know Daddy’s not in bed sick any more. It’s wonderful. I’m wore out. I never knew that first grade and kindergarten had homework that was so complicated.”

With addictions and deaths on upswing, how to increase addiction docs?

Prescription and illicit opioids are the

“main driver of drug overdose deaths,” according to the CDC, with 33,091 deaths in 2015. That’s four times more than 1999. And between 2014 and 2015, Tennessee saw a 13.8 percent increase in opioid deaths. More than 1,000 people died from opioid overdoses in 2014, and tens of thousands of people lead desperate lives, most of them unknowingly fueled by their childhood experiences.

"Only 10% of these are getting the help they need," says Sumrok.

Dan Sumrok is just one doctor, in one part of the country. How can what he does be scaled up to thousands of physicians who can treat addiction — all types of addiction — successfully in all parts of the U.S.? By doing what Dr. David Stern, Robert Kaplan executive dean and vice-chancellor for clinical affairs for the University of Tennessee’s College of Medicine and the University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center, did: launch the Center for Addiction Science.

“This really starts with Dr. Altha Stewart, who’s the director of the Center for Health in Justice-Involved Youth,” says Stern.

“She’s the one who showed me that kids with high ACE scores end up in trouble. When I developed the Center for Addiction Science, it had to be like a cancer center, it had to be multi-disciplinary. In the old days, we thought people who had addictions were weak in the moral department. You really needed someone to straighten you out, because your mother didn’t do a good enough job.”

But that approach doesn’t work. Neither does criminalizing addictions.

"Stigma drives problems underground," says Stern,

"instead of driving them to a solution." The center is taking an integrated approach to using research and education to help people in all possible ways, from physiology to genetics to counseling.

Stern believes that every physician should know about ACE science, which is one of the reasons he chose Sumrok to lead the center, along with his willingness to be creative and seek solutions across disciplines.

“Two of the most prevalent things in acute care are depression and addiction,” says Stern.

“I think it’s important to be able to understand what ACE mean to patients, what addiction is all about, how to recognize it, how to treat it.” He’s in the process of finding an associate dean for medical education, and is looking for someone who will integrate ACE and other social determinants of health into the school’s curriculum.

“I think a medical school should provide for the community it serves,” says Stern.

“This medical school should be the medical school for Memphis. We should develop solutions that are scalable.”

Dr. Altha Stewart, associate professor of psychiatry in the University of Tennessee College of Medicine, learned about ACE in 2009 when a group in Shelby County began educating people about ACE science. They brought Dr. Vincent Felitti, co-founder of the ACE Study, and Robin Karr Morse, who wrote

Ghosts from the Nursery: Tracing the Roots of Violence, which was published in 2007, to give a presentation.

Dr. Altha Stewart

“It’s become a core part of what I do now in my professional work,” says Stewart, who was recently named president-elect of the American Psychiatric Association. She’s working with the Shelby County community and the local criminal justice system to integrate trauma-informed and resilience-building practices to find ways to help youth who enter the justice system — all of whom have likely experienced ACE — instead of shaming, blaming or punishing them.

The things that have happened to kids — as well as to many people who come into the health care system — are out of their control, says Stewart.

“When you’re a child, you don’t control the people who abuse and assault you, who create hostile environments, who don’t provide you with clean clothes,” she says.

“If a child can’t control their environment, because of these things they grow up thinking they’re bad, different, horrible people. This new approach (integrating trauma-informed and resilient-building practices based on ACE science) helps them feel like they’re not drowning anymore. When they can pop their head out of the water and get a breath, and see outstretched hands, a life preserver, a life boat, that changes their entire perspective.”

"When Sumrok began integrating ACE into addiction treatment, that was innovative," says Stewart.

“If you don’t ask these questions, people tend not to tell you,” she says. Sumrok’s approach is part of a shift in patient engagement and involvement.

“The trend in health care is that patients are partners in their treatment.”

"This new knowledge about why and how humans behave the way they do also speaks to how we have trained the medical profession,” says Stewart.

"The traditional approach is that physicians “know everything. The people whom we treat know nothing. We tell them what to do, and if they don’t get better or do what we say, it’s their own fault."

“That’s simply not true,” she emphasizes.

“Some of us have come to understand that there’s more expertise in the community and our patients than we’ve understood. That takes a bit of humility on the part of a physician, and an understanding that we are partners in helping a person heal.”

Sumrok’s experience with the young fellows at the Center for Addiction Science is giving him some real hope that the medical profession can change. When he’s explained to them how important it is to ask patients about ACE and other aspects of their lives — such as food availability, safe housing, transportation, jobs (in the medical profession vernacular: social determinants of health) —

“they say ‘isn’t that just taking a patient history?’”

He and others at the University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center have an opportunity to educate young physicians outside the state, too. Derefinko is also director of the newly created National Center for Research of the Addiction Medicine Foundation. The foundation oversees the 130 addiction medicine fellowships at 46 medical schools across the country.

“We want metrics to understand the impact they’re having when they go out in the world," says Derefinko:

"where they go, whom they’re treating, how they’re practicing, whether they’re integrating ACE science. In addition, the foundation will be developing some accreditation guidelines, so that all fellows receive the latest and best education in addiction medicine."

"One of those elements," says Sumrok,

"has to be empathy, which physicians can practice by listening, acknowledging and understanding how the experiences in a person’s childhood and adulthood have shaped their lives and health."

“Can you teach empathy?” he asks.

“Can people learn to be empathetic providers? I think you can. I think so.”

*From the article here :