Embracing Ecstasy

by Liza Gross | The Verge | May 22, 2019

On a chilly spring morning in 2017, Boris Heifets took the podium to talk about MDMA in an Oakland, California, hotel ballroom packed with scientists, therapists, patients, and activists. If he noticed the occasional whiffs of incense and patchouli oil coming from the halls of the Psychedelic Science meeting, he didn’t let on. After all, anyone studying the therapeutic benefits of the drug that sparked an underground dance revolution 30 years ago knows that ravers, Burners, and old hippies flock to this meeting. It’s the world’s largest gathering on psychoactive substances.

Ecstasy enthusiasts and university professors alike heard several research teams report that MDMA helped patients recover from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other disabling psychiatric conditions after conventional treatments had failed. Meeting rooms buzzed with excited chatter about the prospect of MDMA getting approved as a prescription therapy for PTSD. That could come as early as 2021 if it proves safe and effective in large clinical studies that are just getting underway. For many advocates of this work, regulatory approval can’t arrive too soon.

But Heifets, a Stanford neuroanesthesiologist, had come to lay out an even grander role for the drug federal officials banned in 1985 in a futile effort to quash the burgeoning rave scene. Psychiatric treatments lag decades behind the rest of medicine, even though serious mental disorders carry just as much risk of disability and death as cardiovascular disease, Heifets explained. Psychiatrists desperately need more targeted therapies to give their patients the same kind of rapid, enduring relief that stents and bypass surgery provide for heart patients. He thought they’d benefit from thinking like surgeons.

“I don’t want to suggest that we can cure psychiatric disease in 30 minutes in the operating room,” Heifets said.

"But we can harness powerful drugs like MDMA that act like a surgeon’s knife to alter consciousness and exorcise psychological demons."

For many at the meeting and in the reemerging field of what some call psychedelic medicine, there’s no reason to look further than MDMA. A few hours after Heifets spoke, two therapists who used MDMA in sessions with 28 PTSD patients in Colorado reported that 19 participants no longer met the criteria for their diagnoses a year after treatment.

"MDMA helps melt the walls people hide behind to protect themselves," said Marcela Ot’alora, the principal investigator of the study.

"That allows patients to explore the coping strategies that have failed them for so long." Other teams reported encouraging results from small studies using MDMA to alleviate severe anxiety in adults with autism and in people confronting life-threatening illnesses.

"MDMA’s therapeutic power may come from strengthening the bond between therapist and patient by enhancing feelings of trust, emotional openness, and empathy," Heifets told the audience, pointing to the commentary he and his mentor, Robert Malenka, published in the journal Cell. To his surprise, a few therapists approached him after the talk to say they quote the paper to tell their patients that the world needs more empathy.

There’s no question that MDMA is showing therapeutic promise and could potentially help a range of socially debilitating disorders, Heifets allows. But MDMA, an amphetamine derivative, can raise heart rate and blood pressure, which can prove dangerous for people with cardiac and vascular problems. Though ecstasy is almost never pure MDMA, recreational use can cause panic attacks. In rare cases, it can trigger psychosis in susceptible individuals, which is an unnerving experience ravers have shared on Reddit. Such risks, combined with its bad rap as a party drug, may limit its ability to help patients, Heifets cautions. He’s convinced that MDMA has an even greater potential to revolutionize psychiatric care by giving scientists clues about how to develop next-generation drugs. Ideally, those drugs would be more clearly targeted and have fewer risks than MDMA. Potentially, they could even treat more disorders.

If psychiatrists are ever going to catch up with the rest of medicine, they need a better understanding of how the brain works so they can guide it back to health when it breaks down. MDMA is the only psychoactive drug that enhances positive social interactions and empathy. Heifets believes this offers researchers a unique opportunity to probe the brain.

The same properties that make ecstasy-fueled ravers hug between dance grooves also make the drug uniquely suited to help scientists figure out how the brain supports social behaviors. Because its powerful effects don’t last long, researchers can model those behaviors in animals and link them to cellular networks in the brain.

"Go to a rave, and you’ll find people glassy-eyed, staring inches from each other’s faces in rapt conversation," Heifets says.

"What they’re saying doesn’t matter. The deep emotional connection they’re experiencing, however, does. That’s what we’re after. How can we bottle that?”

If scientists can capture that magic, he believes, they can sidestep the inherent difficulties of working with a demonized substance steeped in the trappings of a subculture that still inhabits the fringes of society. After the Colorado investigators described how they used MDMA in therapy, a woman in the audience complimented them on the power of their aura, which she said was violet blue and “pretty incredible.” After a brief pause, Ot’alora smiled and thanked the woman, who said she works in the Akashic Records, described by adherents as a sort of cosmic transcript of everything that has ever happened in the history of the world.

Talk of auras and Akashic Records comes with the territory at a meeting with “psychedelic” in the name, and most researchers take it in stride. They’re waiting to see if mainstream medicine will embrace MDMA, assuming the promising results from early PTSD studies hold up under the scrutiny of the larger clinical trials. But Heifets doesn’t want to take any chances that shifting political winds will once again shut down work with the still-popular club drug — along with any hope of ushering in a new era of psychiatry.

Heifets works in Malenka’s lab in one of the nation’s largest regenerative medicine facilities. The center was built a decade ago to foster groundbreaking therapies for some of medicine’s most intractable diseases. A massive Chihuly chandelier hangs just inside the center’s front entrance where the sculptor’s trademark glass tendrils evoke the networks of neurons that hold the secrets to health and disease. It’s just a short walk from the lab to the hospital where Heifets spends one day a week tending to brain surgery patients.

Heifets didn’t set out to study a controlled substance.

“My mom told me I should never study psychedelics,” he says with an impish grin.

“It’s a good way to kill a promising career.”

Still, MDMA piqued his interest even as an undergrad. So when he wandered into Malenka’s lab one day and heard him speaking with a colleague about a controlled substance application to do research with MDMA, he went “full in.”

Heifets was just seven years old in the summer of 1984 when the Drug Enforcement Administration proposed new rules to ban MDMA under Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, citing “illicit trafficking,” high abuse potential and “no legitimate medical use.”

"By then, ecstasy had become so popular," Heifets says,

"that you could buy it with a credit card over the counter at clubs in Texas."

The allure of MDMA’s feel-good effects has captured the imagination of adventurers ever since a trailblazing cadre of psychotherapists started using it in the late 1970s. MDMA was discovered in 1912 by German chemists looking for drugs to stop bleeding. It was rediscovered in 1976 by chemist Alexander Shulgin. The legendary psychedelic chemist famously cataloged the effects of nearly 200 psychedelic compounds he’d made in his home lab. He reported feeling “pure euphoria” on MDMA, which he called his “low-calorie Martini” with the “special magic,” and shared the compound with psychotherapists he thought might find it of use.

Those therapists had seen more than a thousand MDMA-assisted breakthroughs with patients, with no major side effects, by the time the government moved to criminalize the drug. Many of them petitioned federal officials to keep it available for their patients. Philip Wolfson, a San Francisco-area psychiatrist who’d used MDMA in hundreds of therapy sessions, testified that the drug had helped patients in severe emotional distress with a poor prognosis.

“I am extremely concerned that this promising new psychotherapeutic agent will be lost to the medical profession,” he said.

The government’s campaign to ban a drug with potential medical benefits caught the attention of the era’s king of daytime talk TV, Phil Donahue. In 1985, he devoted an entire show to MDMA.

“It makes you love everybody,” Donahue said.

“Now, who doesn’t want to take ecstasy?” Several people on the show explained how MDMA had helped them come to terms with life-threatening illnesses and heal fractured family relationships in therapy. Chicago addiction expert Charles Schuster, however, said he had “great concern” about MDMA because he and his colleagues had found that MDA, a chemical cousin, produced long-term brain damage in rats.

“If MDA does this,” Schuster warned,

“then I have reason to suspect that MDMA may as well.”

That was all DEA deputy assistant administrator Gene Haislip, who also condemned MDMA on Donahue’s show, needed to hear. A month after appearing on Donahue, Haislip announced an emergency ban on MDMA.

The DEA’s ban effectively shut down research on MDMA’s medical benefits, but it did nothing to stop the explosion of underground ecstasy-fueled parties where DJs prided themselves on spinning the most eclectic electronica. Filmmakers mined raves’ trance-inducing beats and light shows as the backdrop for thrillers, crime capers, documentaries, and love stories. Irvine Welsh of Trainspotting fame explored his fascination with “rolling” on ecstasy in a collection of “chemical romance” stories, one of which was eventually adapted for the big screen.

Meanwhile, Schuster was tapped to head the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), which showered scientists investigating MDMA’s toxicity with millions of federal dollars. It didn’t take long for the NIDA’s investment to pay off. In 2002, researchers led by George Ricaurte — a co-author on Schuster’s MDA study — reported in the prestigious journal Science that recreational doses of ecstasy could cause permanent brain damage in monkeys and possibly lead to Parkinson’s disease. Psychiatrists familiar with the drug questioned the plausibility of the $1.3 million study, which was funded partly by grants on methamphetamine toxicity. Politicians, meanwhile, cited the research to push the Illicit Drug Anti-Proliferation Act — originally introduced in 2002 by Sen. Joe Biden (D-DE) as the Reducing Americans’ Vulnerability to Ecstasy (RAVE) Act — to imprison and fine club owners and promoters for allowing MDMA on their property.

Five months after Congress passed its anti-rave legislation, Ricaurte reported that he’d mistakenly given his animals meth, not MDMA, and retracted the paper. The fiasco, described as an “almost laughable laboratory blunder,” got its own chapter in the book When Science Goes Wrong: Twelve Tales from the Dark Side of Discovery. But the damage had been done. Federal officials continued to bankroll their preoccupation with proving that MDMA causes brain damage while ignoring known risks along with its healing potential.

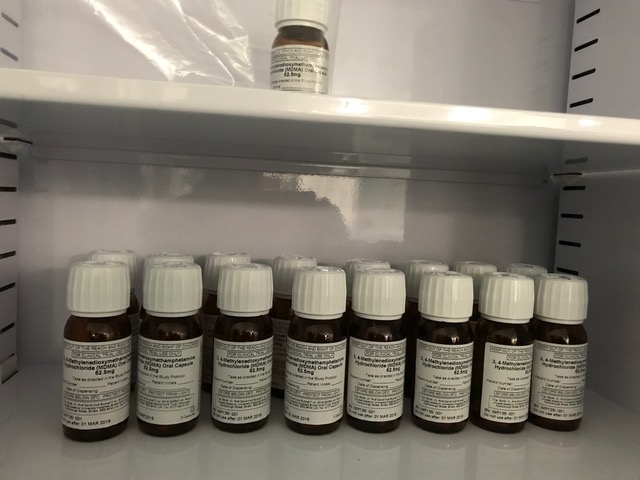

It took researchers almost 20 years after the ban to get federal permission to test MDMA as an experimental therapy. But federal agencies don’t fund clinical studies on the drug, forcing researchers to rely on nonprofit sources such as the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS).

MAPS director Rick Doblin, who founded the organization in 1986, has been instrumental both in getting the Food and Drug Administration’s permission to test MDMA in people and in shepherding it through the drug approval process. Although MDMA could gain FDA approval for PTSD within two years, Doblin is working to make it available as soon as August under the agency’s expanded access program.

"The program gives patients with severe or life-threatening illnesses access to experimental drugs when no other suitable options exist. They’ll have to pay for the drug themselves and recognize that there could be risks since the drug hasn’t been approved yet," Doblin explains.

"To qualify for the trial, patients will need to have PTSD and tried multiple therapies that didn’t work. MAPS is training therapists to work with MDMA, and it’s setting up expanded access sites around the country," Doblin says.

While Doblin’s trying to make up for time lost to restrictive drug laws, Heifets worries about moving too fast.

“MDMA might work for a lot of people, but there’s going to be a large subset for whom it may create problems,” he says. The clinical trials exclude people with conditions that MDMA might exacerbate, and they give the drug under closely supervised conditions. Using pure MDMA in this way has revealed minimal risks.

That’s not what concerns Heifets. Rather, he’s concerned about what might happen if MDMA is given in unrestricted, unsupervised settings.

"Say therapists use the drug without following the carefully crafted MAPS protocol. Who will help people manage the tidal wave of emotions that come up without feeling overwhelmed? Plus, some psychiatric drugs don’t mix with MDMA, so patients will have to be weaned off their meds," Heifets says.

“Who’s watching that process? We’re in new territory here.”

"Ideally, everyone who provides MDMA-assisted therapy will have received MAPS training. But expanding use from a few hundred to the millions of people with PTSD raises the potential for a susceptible person to have a bad reaction that triggers another government backlash," Heifets says.

“How are we going to avoid that outcome this time?”

That’s why he wants to focus on nailing down the brain networks associated with MDMA’s heightened feelings of emotional closeness and empathy. Learning how MDMA works could point to other treatments, maybe ones with fewer risks.

Heifets knew he wanted to study the brain from an early age. But at medical school, he grew increasingly frustrated with his profession’s failure to help people. During a rotation at the Bronx Psychiatric Center, where most patients had failed to respond to every treatment offered, it hit him just how little doctors knew about the roots of psychological distress.

“I was so dissatisfied with our ability to do anything,” he says.

A stint in the operating room gave him hope that he could find a way to help people.

"Psychiatrists are stuck with “wimpy,” often ineffective drugs that take weeks or months to kick in," he says. But anesthesiologists have access to the most powerful psychoactive drugs in the hospital and can monitor major changes in consciousness in ways that aren’t possible outside the OR. That’s when he started thinking: what if psychiatrists could harness potent consciousness-altering drugs to heal broken brains the way cardiologists use surgery to repair broken hearts?

“This is really where psychiatry meets anesthesia,” he says. Anesthesiologists rely on potent drugs that quickly alter consciousness so surgical patients don’t feel physical pain. Similarly, psychiatrists working with drugs like MDMA can harness fast-acting mind-bending drugs to mold the brain’s perception of psychological distress. Researchers reported 20 years ago that MDMA, in the proper therapeutic setting, alleviates the fear that prevents patients from revisiting traumatic events, a vital part of the healing process. Exactly how MDMA does that still remains unclear.

A few years ago, the Department of Veterans Affairs declared psychotherapy to be the definitive treatment for PTSD; conventional drugs mostly just mask symptoms. But therapy often fails because people can’t bear to relive their trauma. Studies show an increased risk of suicide for veterans with PTSD. Effectively, people are dying for want of better therapies. The success stories from when MDMA was still legal convinced second-generation researchers like Michael Mithoefer that the drug might jump-start the psychological healing process. But whether it could pass muster as a standard treatment had never been pursued in formal research until Mithoefer, a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at the Medical University of South Carolina, launched the first study with MAPS nearly two decades ago.

Today Mithoefer, a PTSD specialist, is overseeing clinical trials of MDMA-assisted therapy for hundreds of patients at 15 sites in North America and Israel. If all goes well in these formal studies, MDMA could get the green light from the FDA as a prescription drug for PTSD within two years. He’s cautiously optimistic.

“We have to wait to see the results before we can say that we’ve definitively established safety and efficacy,” Mithoefer says.

“It’s looking promising, but we need to see what happens.”

To get FDA approval, Mithoefer and his team don’t have to show how MDMA works. (

“If we did, Prozac would never have been approved,” he says.)

"Still", he says,

"there may well be other drugs that are even better than MDMA."

As far as MAPS’s Doblin is concerned, there’s no point in trying to find another MDMA-like drug when the real thing is showing such progress.

“Alexander Shulgin tinkered with the molecule in hundreds of different ways, but ended up feeling that of all the ones that he did actually produce MDMA was still the best at what MDMA does,” he says.

Doblin allows that drug companies could potentially improve on MDMA. But they’ve shown little interest in a controlled substance with an expired patent that can’t deliver a fast return on investment. And nonprofits like MAPS don’t have the resources to invest in drug discovery or to produce the amount of safety data the FDA requires.

A lot of that safety data, ironically, came from government efforts to demonize the drug, to no avail.

“Big governments all over the world have spent hundreds of millions of dollars trying to identify the risks,” Doblin says.

“So we have summarized the world scientific literature on MDMA and presented that to FDA.”

Aside from elevated heart rate and blood pressure, the risks include overheating and water intoxication. But it was nothing like the long-term brain damage NIDA seemed so intent on proving. Doblin envisions a day when MDMA will be available far beyond the clinic for everything from couples therapy to personal growth.

It’s a prospect that concerns some psychiatrists, including Charles Grob who led a recent study using MDMA to ease severe anxiety in autistic adults.

"The idea of millions and millions of people taking MDMA “makes me dizzy,” says Grob, director of the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles.

"MDMA needs to be administered by trained professionals in special settings with clear-cut safety parameters," he says. Without these measures in place, he worries about

“the whole enterprise going off the rails.”

Marcela Ot’alora, who runs the MAPS PTSD study in Colorado, agrees that MDMA may not be for everybody. About three-quarters of PTSD patients in her study learned to cope with their symptoms, but that leaves a quarter who did not.

“It’s great if we can find something else that maybe would help people that are not going to be helped by MDMA,” she says.

That’s another thing that suggests Heifets’ approach might be a good one: finding better treatments depends on getting a better handle on how they work, which is insight that’s missing for most psychiatric drugs.

"Scientists stumbled upon the original antidepressants by accident: patients who took new drugs for tuberculosis in the 1950s reported feelings of euphoria. That led to theories about tinkering with neurotransmitters to improve moods and decades of drug development. That pipeline, however, is now dry," Heifets says.

Both Prozac — a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) — and MDMA affect the same brain chemical: serotonin, which regulates mood, learning, and memory. But no one gets an insatiable urge to approach strangers after taking Prozac, Heifets points out. Clearly, they act in different ways.

"Psychiatrists have long treated the brain as a chemical soup and enlisted drugs to target one chemical after another," he says.

"But those drugs can cause terrible side effects because they’re not specific enough. Increasingly, researchers view psychiatric disorders as changes in the connections between specific groups of cells, or circuits, in the brain. Different regions of the brain talk to each other to support normal responses to everyday events, like meeting strangers or navigating potential threats. When those lines of communication between circuits break down, normal responses do, too. Figuring out how MDMA changes these connections to enhance emotional closeness may help explain what goes wrong in people who can’t manage social situations," Heifets says.

"In general, psychiatry hasn’t paid much attention to how social factors affect mental health," says Harriet de Wit, director of the University of Chicago’s Human Behavioral Pharmacology Laboratory.

"Yet depression, schizophrenia, and psychosis, for example, share a strong sense of withdrawal from social interactions and society, even though the underlying process likely differs," she says.

"A better understanding of how MDMA works might point to other drugs that can specifically affect the different social processes."

Heifets has been trying to do just that under the guidance of Malenka, a leader in enlisting cutting-edge tools in rodents to understand how changes in brain circuits affect behavior.

“Rob’s been my biggest advocate and mentor,” Heifets says.

“I’m the only one in the lab working on MDMA.”

“This is where Boris and I bonded,” Malenka says.

“It’s just a fascinating drug that I’ve been wanting to study for, my god, probably over 30 years because I think it’s a window into the brain and how the brain works.”

Malenka believes MDMA could ultimately help people whose illness makes healthy social interactions difficult or impossible.

“Imagine going through life where you can’t have a positive social experience,” he says.

“MDMA really taps into something that enhances the ability to have the most positive social experience.” But where Doblin sees a role for MDMA for everything from PTSD to personal growth, Malenka sees a powerful compound with the potential to harm as well as heal.

"That’s not demonizing the drug," he says,

"but recognizing the need to understand the good and the bad." For Malenka, MDMA is like any other substance that can affect brain function.

"Drilling into the details of how it works will help clinicians make rational decisions about how to use it," he says.

Toward that end, Malenka hopes the experiments they’re doing in mice will influence the clinical studies by showing, for example, that a specific brain circuit isn’t functioning properly in a specific psychiatric disorder. That, in turn, could suggest new therapies that drug companies would be willing to invest in.

Recent work from Malenka’s lab shows that the release of serotonin in a region of the brain’s “reward circuit” — which reacts to pleasurable activities like eating and sex — can enhance social behavior in mice bred to have autism-like behaviors. Research from other groups working in mice showed that MDMA increases “fear extinction,” a decline in fear responses triggered by trauma, which appears to be critical for successful PTSD therapy.

"MDMA may be acting like a sort of psychological accelerant, hastening changes in the brain that lay the groundwork for recovery. The idea of starting a process as a bridge to healing is a concept that’s been missing in psychiatry," Heifets says.

"The trick is figuring out novel or existing drugs that can build that bridge. We probably have a ton of drugs that are already FDA approved that we just don’t know what their potential is,” he says.

Beyond exploring how MDMA works in the brain, psychologists are still figuring out how it works in the therapist’s office.

“We’re still kind of waving our hands around,” says de Wit.

“There’s general agreement that it’s not just the drug itself, but it’s the combination of how the drug changes the therapeutic interaction. I don’t think we know enough about what happens in therapeutic interactions to know whether it’s something about the connection that the patient feels with the therapist or their willingness to be open about their emotions or whether they feel less judged.”

Whatever is going on is a radical departure from standard psychiatric treatments. Rather than taking SSRIs indefinitely to keep symptoms from returning — assuming they ever go away — patients take just a few doses of MDMA in therapy and experience lasting relief.

At the Oakland Psychedelic Science meeting, where Heifets spoke two years ago, several practitioners emphasized the power of the relationship between therapist and patient to aid recovery. Psychiatrist Philip Wolfson, who urged the DEA to keep MDMA legal in the 1980s, said that MDMA revolutionized psychotherapy in part because therapists had to stay with people for as long as they needed.

“That meant we exposed ourselves more as therapists,” he said.

“And we changed from the 50-minute hour, which was always repugnant to me.”

Wolfson reported preliminary results from sessions using MDMA in 18 patients facing life-threatening illnesses. His study, like other MAPS-funded studies, involved intensive psychotherapy lasting at least eight hours in three sessions. The initial analysis for a subset of patients showed marked improvement in scores for both depression and fear of dying for those who took MDMA. But patients who took placebos also improved, a result Wolfson attributed to the effects of such intensive psychotherapy. Even so, after he recently finished the full analysis, it was clear that the MDMA group had the bigger drop in anxiety compared to the placebo group. Everyone had the option to do a follow-up MDMA session, he told me. Everyone opted for MDMA, and everyone felt even better as a result.

Ot’alora, the PTSD researcher who handled the compliment on her aura without missing a beat, has seen similar therapeutic breakthroughs without MDMA. But it can take years.

"With MDMA sessions, people often show improvement right away," she says,

"as the drug gives them the inner resources to work through their trauma. Even people who still had trouble coping with their PTSD symptoms after the treatment said it helped them when nothing else had," she says.

“Every single participant I’ve worked with has said, ‘I don’t understand why this is not available to everybody who’s suffering.’”

Researchers feel buoyed by the promising results. Yet they’re keenly aware of the stigma around drugs like MDMA.

“Now we have data saying that, yes, this is actually helping. It’s no longer anecdotal,” says Ot’alora.

“And there are still people who are incredibly skeptical.”

Blame George Ricaurte’s fateful lab blunder. It doesn’t matter that his paper was retracted. It’s still on the internet, including the NIDA’s website.

"Even today," Ot’alora says,

"people tell her they read that MDMA causes holes in your brain. And she’s seen both patients and parents of younger patients bristle at the idea of using what they see as a club drug for therapy — until they see the results."

For years, meetings like Psychedelic Science were the only place scientists researching psychoactive drugs were invited to speak.

“The government and industry have not put one cent into this research, so it has to be supported by donors,” Mithoefer says.

"Still, attitudes among psychiatrists have changed radically since the first MDMA studies," Mithoefer says. Now, he and his colleagues are presenting their work mostly at mainstream meetings where he’s seeing a lot of excitement around the idea that drugs like MDMA can trigger a therapeutic process with higher rates of success.

“And nobody’s bringing up their auras,” he says with a laugh.

And now, scientists who study MDMA don’t have to worry about throwing away their careers.

For Heifets, one of the most intriguing things to come from lab work on MDMA is the notion that a drug can strengthen the bond between patient and therapist.

“There’s no real precedent for that in psychiatry,” he says.

"And that may be where the path to transforming psychiatry begins: in abandoning the notion that you can treat complex human brain disorders with drugs alone. It’s time to recognize that you can’t treat millions of veterans with PTSD by giving them a pill, whatever it is, and sending them home," Heifets says.

"The research on MDMA is showing that you might be able to kick off recovery with a drug, but interaction with other people matters, too. In fact, the relationships with other people — like therapists — may matter even more."

“Fundamentally, there is a need for some kind of human connection,” he says.

“We can’t just farm out all of our psychiatric issues to the drug industry.”

One researcher wants to find out how the drug works — to make other mental health treatments

www.theverge.com