Psychedelic drugs and the future of mental health care

by Sean Illing | Vox | Mar 8, 2019

I had a close call on the second night of the ayahuasca ceremony.

I saw my teenage self melting into particles and eventually disappearing altogether. I pulled off my sleep mask and saw the people around me shape-shifting into shadows. I thought I was dying, or perhaps losing my grip on reality.

Suddenly, Kat, my guide, appeared and began singing to me. I couldn’t make out the words, but the cadence was soothing. After a minute or two, the dread washed away and I settled back into a peaceful half-sleep.

The 12 of us — nine women and three men — taking ayahuasca in a private home in San Diego were led by two trained guides: Kat and her partner, whom I’ll call Sarah since she requested anonymity due to legal concerns. Together they have more than 20 years of experience working with psychedelics, including ayahuasca, a plant concoction that contains the natural hallucinogen known as DMT.

Kat and Sarah work as a team serving psychedelic medicine every month or so in a different city. Their primary role is to create a space in which everyone feels secure enough to drop their emotional guards and open up to the drugs’ potential to change their attitudes, moods, and behaviors.

There’s a lot of unease heading into these ceremonies, especially for people who have never experimented with psychedelics. The fear of what you might see or feel can be overwhelming. But guides like Kat are your port in the storm. When things get turbulent, they respond with a steady, calm hand.

Though psychedelic drugs remain illegal, guided ceremonies, or sessions, are happening across the country, especially in major cities like New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Guiding itself has become a viable profession, both underground and above, as more Americans seek out safe, structured environments to use psychedelics for spiritual growth and psychological healing. This new world of psychedelic-assisted therapy functions as a kind of parallel mental health service. Access to it remains limited, but it’s evolving quicker than you might expect.

But what would a world in which psychedelics are legal look like? And what sort of cultural structures would we need to ensure that these drugs are used responsibly?

Today, a renaissance is underway. At institutions like John Hopkins University and New York University, clinical trials exploring psilocybin as a therapy for treatment-resistant depression, drug addiction, and other anxiety disorders are yielding hopeful results.

In October, the Food and Drug Administration took the extraordinary step of granting psilocybin therapy for depression a “breakthrough therapy” designation. That means the treatment has demonstrated such potential that the FDA has decided to expedite its development and review process. It’s a sign of how far the research and the public perception of psychedelics have come.

It’s because of this progress that we have to think seriously about what comes next and how we would integrate psychedelics into the broader culture. I’ve spent the past three months talking with guides, researchers, and therapists who are training clinicians to do psychedelic-assisted therapy. I’ve participated in underground ceremonies, and I’ve spoken to people who claim to have conquered their drug addictions after a single psychedelic experience.

Our current laws sanction various poisons, including booze and cigarettes. These are drugs that destroy lives and feed addictions. And yet one of the most striking things about the recent (limited) psychedelic research is that the drugs do not appear to be addictive or have adverse effects when a guide is involved. Many researchers believe these drugs, when used under the supervision of trained professionals, could revolutionize mental health care.

Psychedelics are becoming tools of healing rather than a threat to the social order. And the scientists and organizations and training institutions leading the way are working within the system to reduce the potential for blowback. This is very different from the approach taken in the ’60s, and so far it’s been a success.

Your mind on psychedelics

Psilocybin is the drug of choice for most researchers in recent years for a variety of reasons. For one, it carries less cultural baggage than LSD, and so study participants are more willing to work with it. Psilocybin also has strong safety data based on studies conducted before prohibition, and so the FDA has allowed a small number of small clinical trials to move forward.

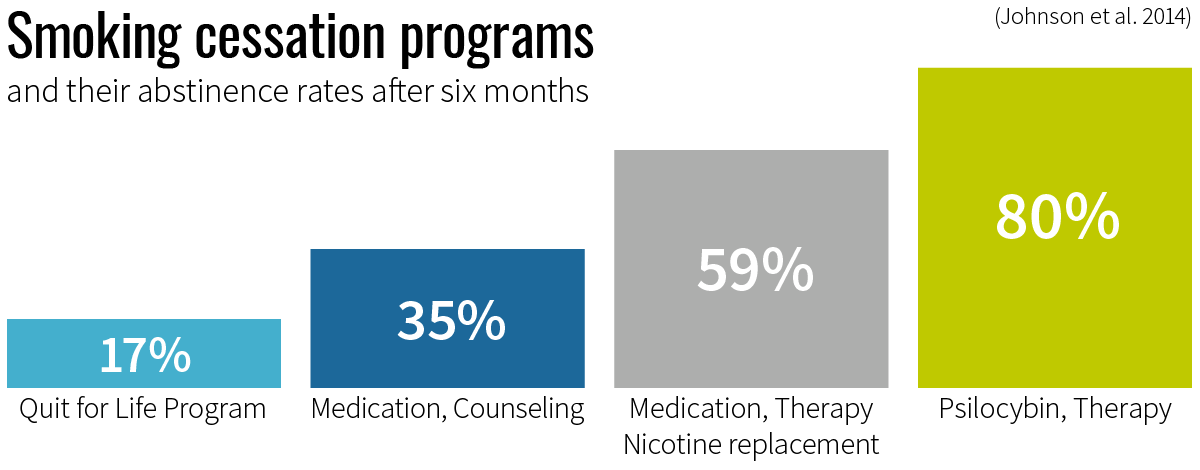

Although the most recent studies are still preliminary and the sample sizes fairly small, the results so far are compelling. In one 2014 Johns Hopkins study, 80 percent of the smokers who participated in psilocybin-assisted therapy remained fully abstinent six months after the trial. By way of comparison, smoking cessation trials using varenicline (a prescription medication for smoking addiction) has success rates around 35 percent.

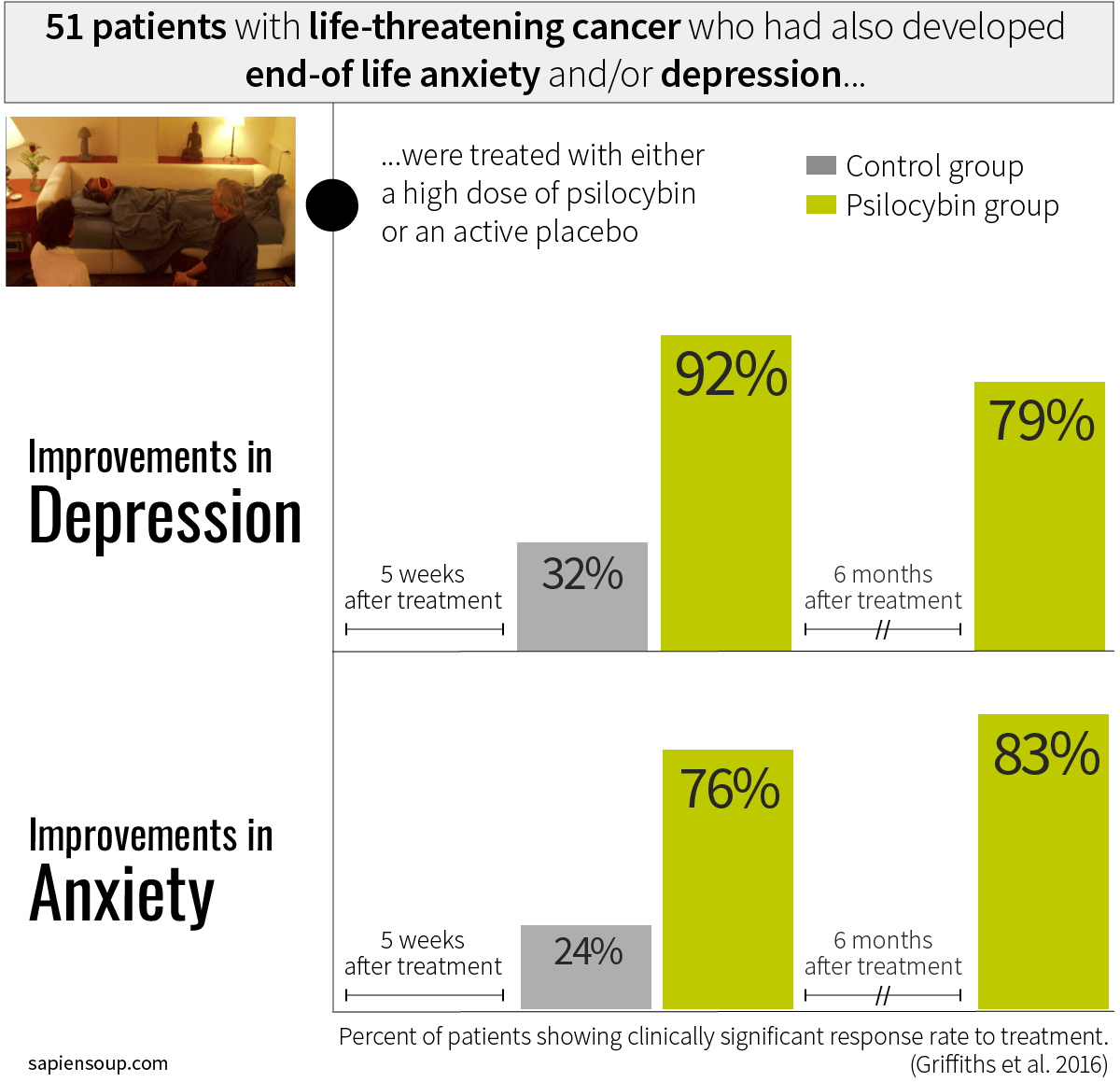

In a separate 2016 study of cancer-related depression or anxiety, 83 percent of 51 participants reported significant increases in well-being or satisfaction six months after a single dose of psilocybin. (Sixty-seven percent said it was one of the most meaningful experiences of their lives.)

A typical psilocybin session lasts somewhere between four and six hours (compared with 12 hours with LSD), yet it produces enduring decreases in depression and anxiety for patients. Which is why researchers like Roland Griffiths at Johns Hopkins believe psychedelics represents an entirely new model for treating major psychiatric conditions. Conventional treatments like antidepressants don’t work for a lot of patients and can come with a host of side effects.

To understand the clinical side, I traveled to Johns Hopkins to sit down with Alan Davis, a clinical psychologist, and Mary Cosimano, a research coordinator and trained guide. Both help lead the psilocybin sessions at Hopkins.

Researchers at Hopkins have worked with a number of populations since they received approval from the FDA to study psilocybin in 2000 — healthy adults without any psychological issues, cancer patients suffering from anxiety and depression, smokers, and even seasoned meditators.

A key part of the process at Hopkins is what they call “life review.” Before they provide the drug, they want to know who you are, where you’re at in your life, and what kinds of emotional or psychological walls you’ve built up around yourself. The idea is to work with patients to determine what’s holding them back in their lives, and explore how they might overcome it.

Davis and Cosimano both say psilocybin has benefited every population they’ve worked with.

“It’s not for everyone,” Cosimano told me,

“but for the right person at the right time, it can be positively transformative.” (They don’t accept patients anywhere on the spectrum of psychosis — it’s just too dangerous.)

The psilocybin sessions are intense and, in some cases, last all day. The rooms they use are a curious blend of drab doctor’s office decor and New Age ornamentation. There’s a vanilla-colored couch covered with embroidered pillows and draped on both sides by South American art. Near the couch, on an end table, is a ceremonial cup and mini sculptures of magic mushrooms; it’s not quite an altar, but it may as well be.

The important thing, Cosimano and Davis say, is to make the patient as comfortable as possible. They even encourage people to bring personal artifacts with them, or letters from loved ones, or basically anything with deep emotional resonance. Much like the underground guides, researchers do everything they can to create a safe psychological space.

Sessions can unfold in multiple directions, depending on the depth of the experience (which is hard to predict) and the mental state of the individual. Mostly, patients are lying on the couch with a sleep mask covering their eyes. Cosimano, Davis, and other clinical guides act as lodestars — holding the patient’s hand and helping them process what they’re seeing and what it means.

“I never get bored with this,” Cosimano told me.

“Every single session is different, every experience is different, and I’m just blown away at being able to witness each person’s journey.”

Yet it’s not entirely clear to the scientists what it is about these experiences that produce such profound changes in attitude, mood, and behavior. Is it a sense of awe? Is it what the American philosopher William James called the “mystical experience,” something so overwhelming that it shatters the authority of everyday consciousness and alters our perception of the world? What’s clear in any case is that psychedelic trips are often beyond the bounds of language.

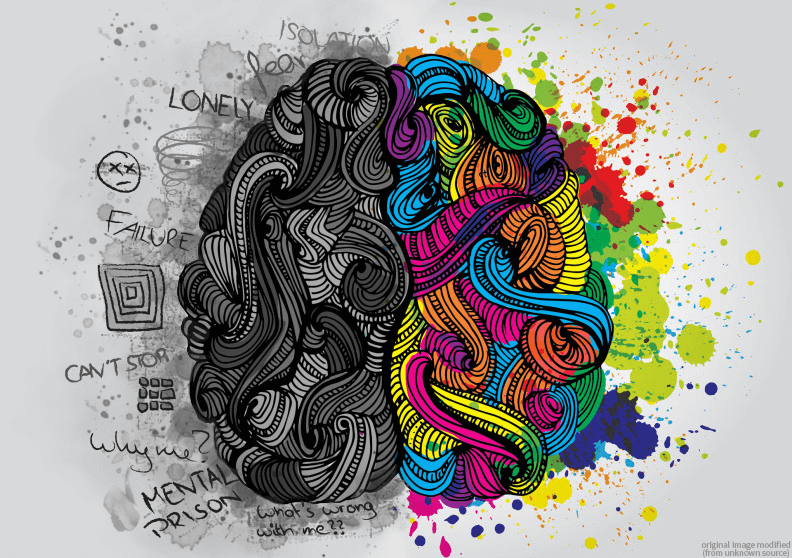

The best metaphor I’ve heard to describe what psychedelics does to the human mind comes from Robin Carhart-Harris, a psychedelic researcher at Imperial College in London. He said we should think of the mind as a ski slope. Every ski slope develops grooves as more and more people make their way down the hill. As those grooves deepen over time, it becomes harder to ski around them.

Like a ski slope, Carhart-Harris argues, our minds develop patterns as we navigate the world. These patterns harden as you get older. After a while, you stop realizing how conditioned you’ve become — you’re just responding to stimuli in predictable ways. Eventually, your brain becomes what Michael Pollan has aptly called an “uncertainty-reducing machine,” obsessed with securing the ego and locked in uncontrollable loops that reinforce self-destructive habits.

"Taking psychedelics is like shaking the snow globe," Carhart-Harris said.

"It disrupts these patterns and explodes cognitive barriers. It also interacts with what’s called the default mode network (DMN), the part of the brain associated with mental chatter, self-absorption, memories, and emotions." Anytime you’re anxious about the future or fretting over the past, or engaged in compulsive self-reflection, this part of the brain lights up. When researchers looked at images of brains on psychedelics, they discovered that the DMN shuts down almost entirely."

Think of it this way: You spend your whole life in this body, and because you’re always at the center of your experience, you become trapped in your own drama, your own narrative. But if you pay close attention, say, in a deep meditation practice, you’ll discover that the experience of self is an illusion. Yet the sensation that there’s a “you” separate and apart from the world is very hard to shake; it’s as though we’re wired to see the world this way.

The only time I’ve ever been able to cut through this ego structure is under the influence of psychedelics. I was able to see myself from outside my self, to see the world from the perspective of nowhere and everywhere all at once, and suddenly this horror show of self-regard stopped. And I believe I learned something about the world that I could not have learned any other way, something that altered how I think about, well, everything.

At Johns Hopkins, the drug experience is only one part of the treatment. Equally important is the therapy that follows. People regularly tell researchers that the psilocybin session is the single most personally and spiritually significant experience of their lives, including childbirth and the loss of loved ones.

"But there’s a need," Davis said,

“to make sense of these experiences and to bring them into your day-to-day life in a way that doesn’t discount the meaning. That doesn’t necessarily have to be therapy or one-on-one counseling with a guide, but it’s crucial to integrate the experience into your daily life, whether that’s taking up a new practice like yoga or meditation, spending more time in nature, or just cultivating new relationships."

The point is that’s it not enough to take the ride and move on; it’s about establishing new habits, new mental patterns, new ways of being. Psychedelics can kick-start this process, but for many people, at least, that’s all they can do.

When I returned from my first ayahuasca retreat, I struggled to process what had happened to me. I had no formal help, no instruction, no real support. It’s jarring to slide back into your routine after having your inner world turned upside down like that. I’ve adopted new practices (like meditation), and that has gone a long way in keeping me connected to that initial encounter with psychedelics, but there are limits to what you can do alone.

Recognizing the need for more integration, schools like the California Institute of Integral Studies and psychedelic researchers like NYU’s Elizabeth Nielson are focused on training professional therapists to work specifically with psychedelic users. Nielson is part of the Psychedelic Education and Continuing Care Program, which does not conduct psychotherapy but offers instruction to clinicians who want to learn about psychedelics.

“People who have used psychedelics, or will use psychedelics in the future, will need help integrating their experiences, and many will feel safest doing that in a therapist’s office,” she told me.

“That means we’ll need more therapists who understand these experiences and know how to have these kinds of conversations with patients.”

So how do we integrate psychedelics into the culture?

For better or worse, psychedelics, like all drugs, are going to be used outside the safer contexts of research facilities or private sessions with experienced guides. According to Geoff Bathje, a psychologist at Adler University who works with high-trauma patients, the question is therefore,

“What sort of harm reductions do we need to help protect people?”

Several people I spoke with pointed to the “harm reduction” model. Harm reduction focuses on reducing the risks associated with drug use, as opposed to punitive models aimed at eliminating use altogether. It’s a practical and humane approach that has worked well in places like Portugal, where all drugs for personal use have been decriminalized.

Although the harm reduction model isn’t typically associated with psychedelics, the principles apply all the same.

For Bathje, it’s about doing good drug education in the general population,

“making sure people understand the risks involved with psychedelics — how they can be misused, how people can be exploited when under the influence, etc.” There are already national harm reduction groups like Zendo Project, which is sponsored by MAPS, that focus on peer-to-peer counseling for people experimenting with psychedelics.

Bathje and some of his colleagues have established a harm reduction group in Chicago called Psychedelic Safety Support and Integration. The goal is to promote safety and help people process their psychedelic experiences. It’s a critical container that brings in the community, spreads awareness of the risks associated with psychedelic drug use, and creates a space for connection.

At the moment, there’s a gap between the harm reduction movement and the psychedelic research community.

“You go to a psychedelics conference and it’s focused on the science and the therapeutic potential,” Bathje said,

“and the general assumption is that if we just produce good science, these drugs will get approved as medicines and everything will just fall into place.”

“If you attend a harm reduction conference,” he added,

“it’s all about cultural change and how politicians don’t care about the science. The focus is much more on organizing and who has the power and how we can reduce risks and do things safely.” This is partly why the harm reduction movement can be useful to psychedelics. Science may be critical to legalization, but public health programs would also have to help integrate these drugs into the broader culture.

*From the article here :

I spent months talking to psychedelic guides and researchers. Here’s what I learned.

www.vox.com

theconversation.com

theconversation.com