mr peabody

Bluelight Crew

- Joined

- Aug 31, 2016

- Messages

- 5,714

Talking ibogaine research for opioid addiction with Thomas Kingsley Brown*

By Jordan May | Psymposia | 12 Dec 2017

Thomas Kingsley Brown, PhD, studied the long-term outcomes of people who received ibogaine for the treatment of opioid addiction. We talked about the results. Read the full series.

Thomas Kingsley Brown began conducting research on ibogaine treatment for drug dependence in 2009, when he carried out interviews with patients at a clinic in Tijuana, Mexico. In 2010, he began an observational study with the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) on the long-term outcomes for individuals who received ibogaine for the treatment of opioid addiction. The study was published in 2017.

Psymposia had the opportunity to speak with Kingsley about his work. Specifically, we explore the methodology and outcomes of the study with MAPS, ibogaine’s mechanism of action, and we pick his brain about the future of ibogaine research and ibogaine’s non-psychoactive analog, 18-MC.

Thomas Kingsley Brown began conducting research on ibogaine treatment for drug dependence in 2009, when he carried out interviews with patients at a clinic in Tijuana, Mexico. In 2010, he began an observational study with the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) on the long-term outcomes for individuals who received ibogaine for the treatment of opioid addiction. The study was published in 2017.

Psymposia had the opportunity to speak with Kingsley about his work. Specifically, we explore the methodology and outcomes of the study with MAPS, ibogaine’s mechanism of action, and we pick his brain about the future of ibogaine research and ibogaine’s non-psychoactive analog, 18-MC.

Thanks for talking with us. So, when did you first hear about ibogaine?

I didn’t know about ibogaine before 2008. A friend of mine was working as a counselor at one of the clinics in Baja, California, and she started talking to me about it. She actually was the one who got me into the research, because she knew I was interested in psychedelics. She introduced me to Rick Doblin at Burning Man one year, I think in 2008, and about a year later MAPS was looking for somebody to do their ibogaine study in Mexico. I was well situated here and I had already started doing interviews with people at the clinic in Tijuana. That was Pangea Biomedics, where Clare Wilkins is director. Anyways, I said, “Well, I’m here in San Diego.” It was a good match, not only for them, but for me.

Could you talk about that study a bit?

We were looking at a treatment for substance abuse, more specifically we were looking at treatment for opioid use disorder. We were looking at opioids in particular for a couple reasons. Opioid addiction seems to be more intractable than pretty much any other kind of addiction, and more people go to treatment for opioids than for any other [substance]. The number one thing that people are going to ibogaine treatment sites for is to treat their opioid addiction.

So we enrolled 30 people in the study, whose primary problem was with an opioid. Roughly half of them were using heroin and the other half were coming in with problematic use of some kind of prescription opioid painkiller, like Oxycontin. We did pre-treatment measures and then did after-treatment by following up in the days after the treatment. I followed up monthly, for 12 months, to see how the treatment was working for them in the long term. That was the basic set up.

So we enrolled 30 people in the study, whose primary problem was with an opioid. Roughly half of them were using heroin and the other half were coming in with problematic use of some kind of prescription opioid painkiller, like Oxycontin. We did pre-treatment measures and then did after-treatment by following up in the days after the treatment. I followed up monthly, for 12 months, to see how the treatment was working for them in the long term. That was the basic set up.

And was it effective? What were the outcomes?

We were looking to answer 2 main questions. One is to see if ibogaine is effective for detox, that is the short term efficacy in regards to whether or not it’s reducing withdrawal symtpoms. We used the SOWS measure, which is a scale of subjective opioid withdrawal symptoms, before treatment and after treatment to see if there was an effect after ibogaine was administered. We looked at 1 month following treatment, and then we followed up at later time points. The second question is, is it effective for reduction in drug use and other associated problem narratives for 12 months after treatment? We found that yes, it’s effective for both detox and reduction in drug use for 12 months.

We found at 1 month that there was a strong effect in terms of drug use severity. We were using what we call the addiction severity index. There’s about 7 different problem areas, including drug use severity. Areas where we found that it had increased were treatment effects in family and social status, and also in legal status. Legal status is asking if you’re in trouble with the law, family/social status is asking how well you get along with people in your life that matter to you. We saw a good treatment effect at 1 month in all 3 of those areas – drug use severity, family/social status, and legal status.

We looked at the time after 1 month and found that the treatment effect was still significant. The scores in those areas were all significantly increased throughout the follow up period, although the strength of the treatment effect did drop off after 1 month, particularly drug use severity. Even though they continued to do well throughout the 12-month period, relative to the pretreatment baseline, the effect wasn’t as strong at later time points as it was at 1 month.

We found at 1 month that there was a strong effect in terms of drug use severity. We were using what we call the addiction severity index. There’s about 7 different problem areas, including drug use severity. Areas where we found that it had increased were treatment effects in family and social status, and also in legal status. Legal status is asking if you’re in trouble with the law, family/social status is asking how well you get along with people in your life that matter to you. We saw a good treatment effect at 1 month in all 3 of those areas – drug use severity, family/social status, and legal status.

We looked at the time after 1 month and found that the treatment effect was still significant. The scores in those areas were all significantly increased throughout the follow up period, although the strength of the treatment effect did drop off after 1 month, particularly drug use severity. Even though they continued to do well throughout the 12-month period, relative to the pretreatment baseline, the effect wasn’t as strong at later time points as it was at 1 month.

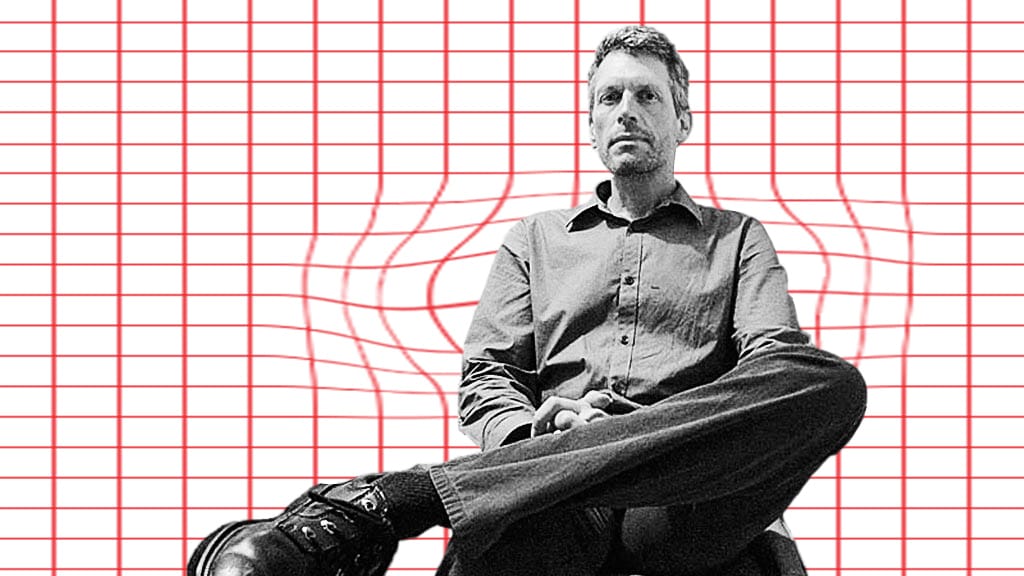

Thomas Kingsley Brown presenting at TedX Venice Beach.

That’s interesting. Could follow-up treatments be useful here for maintaining the initial effect of ibogaine treatment?

I think getting another treatment within 3 to 6 months of the initial treatment is useful for a lot of people. It seems to be effective for people when they relapse or just need to have a booster. The animal studies that were done also show that if you have more than 1 treatment, its more likely to be effective. So on the whole I would say, yeah, if you can get multiple treatments – that’s a good idea.

Another thing that’s also effective is following up with smaller dosages, but there isn’t any research that’s been done with people to see how often that’s necessary.

Was there anybody in the study who it didn’t work for at all?

That’s a good question. Out of the 30 people in the study, there were 3 whose SOWS scores actually increased from pre-treatment to post-treatment. You might say, “Oh, this didn’t work for them.” But those 3 people, their baseline SOWS scores were among the lowest, and they had the least severe withdrawal symptoms going into treatment. It also could be that they were coming off of longer acting opioids like methadone, so it’s not clear what’s going on there.

Everyone in the study stopped using for at least 3 days to a week. There were 15 people in the study who at 1 month had not used any opioids at all. And everybody reduced the amount and the frequency of their opioid use in the months following treatment. So from that perspective I’d say it worked for everybody but it really depends on what you define as efficacy in this case. Some people might say if you relapse at all then it didn’t work. But they did actually stop using for a while, and when they go back to using, the dosage they’re using is a lot less than it was before they were treated. So all in all, I’d say it works for everybody – it’s just a matter of how well it works for them.

What are the potential implications of this study for the future of ibogaine research?

Well, I think the implications are that the Mexico and New Zealand studies are both showing that ibogaine is effective for detox, and for allowing people to significantly reduce their use of opiods. So that’s a big deal all by itself.

In the Mexico study, at least in some ways, it was sort of a worst-case scenario for giving ibogaine. You’re giving somebody this treatment, and then typically 5 to 7 days after, they’re going back home. This is not what you usually want to do if you’re trying to get somebody off of opioids, is put them right back in the context they were using in on a regular basis without any follow up at all. So even though we got good results there wasn’t any follow up. I think one thing that we should be looking at is the potential impact of any follow up care, whether it’s a second or third ibogaine treatment following up with microdosing, psychotherapy, any kind of follow up care. What would be the impact of that?

In the Mexico study, at least in some ways, it was sort of a worst-case scenario for giving ibogaine. You’re giving somebody this treatment, and then typically 5 to 7 days after, they’re going back home. This is not what you usually want to do if you’re trying to get somebody off of opioids, is put them right back in the context they were using in on a regular basis without any follow up at all. So even though we got good results there wasn’t any follow up. I think one thing that we should be looking at is the potential impact of any follow up care, whether it’s a second or third ibogaine treatment following up with microdosing, psychotherapy, any kind of follow up care. What would be the impact of that?

There’s 2 parts to this next question. Firstly, what do we know about ibogaine’s mechanism of action? Secondly, do you think ibogaine’s psychedelic effects play a role in its ability to interrupt addiction, or is it strictly pharmacological?

So to answer the first question, we know a lot about the pharmacology of ibogaine. We know enough to be sure that it doesn’t act in the same way as conventional treatments. It’s not an opioid agonist like methadone or buprenorphine. We also know that it’s acting at many different receptor sites and doesn’t have a strong affinity for any one receptor type. So it’s kind of a dirty molecule in that respect, that it doesn’t really have a clean profile in its activity in different receptors.

That said, we don’t know what its mechanism of action is at the pharmacological level. We don’t know why it’s reducing withdrawal symptoms or why it potentiates the activity of opioids. We don’t know why it reduces cravings either. There aren’t any real clear answers there. So that’s the big question, how is it working? I think there must be some kind of pharmacological mechanism, at least with the reduction in withdrawal symptoms. I just don’t imagine the psychedelic effect having any direct impact on withdrawal symptoms. We know it’s not a placebo effect because placebos aren’t effective for opioid withdrawal. So there’s some kind of underlying biochemical effect that hasn’t been elucidated yet.

As far as reducing people’s use of opioids in the long term, I think there must be some kind of impact from the psychedelic effect. The experiences people have with ibogaine, and the insights they get, must have some kind of effect – but that’s something that hasn’t really been studied very much. There’s a bit of data in our study that seems to indicate some kind of correlation between positive treatment outcomes and the intensity of the effect, in terms of psycho-spiritual impact. But the main reason I think there’s some kind of impact from the psychedelic effect is that people tell me. They have regrets about the way they’re living their life, they have regrets about their relationships with other people in their lives, they see the impact of their behavior and they see where they’re heading if they continue on their current path. It seems like there must be some effect when people have these powerful transformative experiences. That’s my sense of it, anyway.

That’s actually a good segway into the next question. Could you explain what 18-MC is?

18-MC is a synthetic congener to ibogaine, so it’s structurally related. It’s basically using the same chemical backbone that ibogaine has, the same basic ring structure -but its got some different functional groups on it. It’s also been tested in animal studies in the same ways that ibogaine has, and has been shown to be effective in the same sort of ways, reducing withdrawal-like symptoms in animals and also reducing the self administration of drugs.

So it seems to be effective in animal models, but it’s thought that it’s probably not psychoactive. That’s a question that still hasn’t been answered, to my knowledge. I don’t know of anybody who’s ingested 18-MC to be able to say whether or not there’s some kind of psychoactivity. It’s quite possible that there could be, but we don’t know for sure. The company that got a grant to do human studies with 18-MC haven’t released anything about it. I don’t know if they’ve actually carried out the study.

Are there any major barriers to further research with ibogaine?

It’s kind of a complicated answer, but essentially ibogaine is made illegal because it’s psychoactive. So that’s obviously a big barrier to doing research in the US. We’re not allowed to do research on it without getting permission, which hasn’t been granted. There’s also the fact that there are risks associated with ibogaine usage. The estimates are that around 1 in 300 or 400 people will die. That’s actually cited by the FDA as the main reason why they won’t consider taking it off schedule 1.

It’s a legitimate concern, but I think it’s overblown. The risks of not treating people in the midst of this opioid crisis are much greater than the risks of administering ibogaine, especially when you can have medical personnel present during the treatment. There’s no reason not to make ibogaine treatments accessible and available to people in this country. They probably aren’t taking it off schedule 1 anytime soon, maybe ever – but there are states, such as New York and Vermont, looking into possibly allowing its use. They’ve both introduced some legislative efforts attempting to allow ibogaine treatment and research. So maybe at a state level those kinds of changes can be made, and we can work around the federal regulations.

That’d be interesting to see, if different states started to challenge the federal laws on that. It’s one thing to go after medical marijuana; you know the federal government can go into Oakland and shut down a dispensary, but it’d be another thing entirely to try to stop people from getting ibogaine treatments when you have hundreds of people dying from overdoses everyday.

Is there anything you’d recommend for people interested in getting involved with psychedelic research?

For someone who’s interested in psychedelic research, I would say choose a program that will allow you to follow that interest. My advice is to find a graduate program where you can work with somebody who is, if not doing something directly related to what you want to do, at least somebody who you can talk with freely about these substances.

So to answer the first question, we know a lot about the pharmacology of ibogaine. We know enough to be sure that it doesn’t act in the same way as conventional treatments. It’s not an opioid agonist like methadone or buprenorphine. We also know that it’s acting at many different receptor sites and doesn’t have a strong affinity for any one receptor type. So it’s kind of a dirty molecule in that respect, that it doesn’t really have a clean profile in its activity in different receptors.

That said, we don’t know what its mechanism of action is at the pharmacological level. We don’t know why it’s reducing withdrawal symptoms or why it potentiates the activity of opioids. We don’t know why it reduces cravings either. There aren’t any real clear answers there. So that’s the big question, how is it working? I think there must be some kind of pharmacological mechanism, at least with the reduction in withdrawal symptoms. I just don’t imagine the psychedelic effect having any direct impact on withdrawal symptoms. We know it’s not a placebo effect because placebos aren’t effective for opioid withdrawal. So there’s some kind of underlying biochemical effect that hasn’t been elucidated yet.

As far as reducing people’s use of opioids in the long term, I think there must be some kind of impact from the psychedelic effect. The experiences people have with ibogaine, and the insights they get, must have some kind of effect – but that’s something that hasn’t really been studied very much. There’s a bit of data in our study that seems to indicate some kind of correlation between positive treatment outcomes and the intensity of the effect, in terms of psycho-spiritual impact. But the main reason I think there’s some kind of impact from the psychedelic effect is that people tell me. They have regrets about the way they’re living their life, they have regrets about their relationships with other people in their lives, they see the impact of their behavior and they see where they’re heading if they continue on their current path. It seems like there must be some effect when people have these powerful transformative experiences. That’s my sense of it, anyway.

That’s actually a good segway into the next question. Could you explain what 18-MC is?

18-MC is a synthetic congener to ibogaine, so it’s structurally related. It’s basically using the same chemical backbone that ibogaine has, the same basic ring structure -but its got some different functional groups on it. It’s also been tested in animal studies in the same ways that ibogaine has, and has been shown to be effective in the same sort of ways, reducing withdrawal-like symptoms in animals and also reducing the self administration of drugs.

So it seems to be effective in animal models, but it’s thought that it’s probably not psychoactive. That’s a question that still hasn’t been answered, to my knowledge. I don’t know of anybody who’s ingested 18-MC to be able to say whether or not there’s some kind of psychoactivity. It’s quite possible that there could be, but we don’t know for sure. The company that got a grant to do human studies with 18-MC haven’t released anything about it. I don’t know if they’ve actually carried out the study.

Are there any major barriers to further research with ibogaine?

It’s kind of a complicated answer, but essentially ibogaine is made illegal because it’s psychoactive. So that’s obviously a big barrier to doing research in the US. We’re not allowed to do research on it without getting permission, which hasn’t been granted. There’s also the fact that there are risks associated with ibogaine usage. The estimates are that around 1 in 300 or 400 people will die. That’s actually cited by the FDA as the main reason why they won’t consider taking it off schedule 1.

It’s a legitimate concern, but I think it’s overblown. The risks of not treating people in the midst of this opioid crisis are much greater than the risks of administering ibogaine, especially when you can have medical personnel present during the treatment. There’s no reason not to make ibogaine treatments accessible and available to people in this country. They probably aren’t taking it off schedule 1 anytime soon, maybe ever – but there are states, such as New York and Vermont, looking into possibly allowing its use. They’ve both introduced some legislative efforts attempting to allow ibogaine treatment and research. So maybe at a state level those kinds of changes can be made, and we can work around the federal regulations.

That’d be interesting to see, if different states started to challenge the federal laws on that. It’s one thing to go after medical marijuana; you know the federal government can go into Oakland and shut down a dispensary, but it’d be another thing entirely to try to stop people from getting ibogaine treatments when you have hundreds of people dying from overdoses everyday.

Is there anything you’d recommend for people interested in getting involved with psychedelic research?

For someone who’s interested in psychedelic research, I would say choose a program that will allow you to follow that interest. My advice is to find a graduate program where you can work with somebody who is, if not doing something directly related to what you want to do, at least somebody who you can talk with freely about these substances.

The main thing is don’t give up. If you say, “I’m gonna study psychedelics,” don’t let anybody else tell you that shouldn’t do it.

*From the article here :

Talking Ibogaine Research for Opioid Addiction with Thomas Kingsley Brown | Part 5

The Ibogaine Conversation Part 5 | Thomas Kingsley Brown, PhD, studied the long-term outcomes of people who received ibogaine for the treatment of opioid addiction. We talked about the results.

Last edited: