Research Recap 2019: The Year of Preparing for the Future

By Alycia Halladay, PhD, Chief Science Officer and The Scientific Advisory Board of ASF

The ASF Yearly Summary of Science highlights major research accomplishments that directly affect the lives of families with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). These accomplishments impact families in a number of ways: by affording those diagnosed and their families a better understanding of a particular behavior or biological feature; identifying beneficial treatment targets, interventions, services or resources; discovering technologies that not only identify unique characteristics of people with ASD but also offer insight as to how to better serve that population and by offering future predictions.

ASD research continues to be challenged by clinical heterogeneity, a scientific term applied to the variability of symptoms found in subjects across the spectrum. Current research has identified increased diversity amongst people with autism participating in research; in turn, this has led to a reduction across time in differences between people with a diagnosis vs. those without a diagnosis. In other words, those participating in research now show less severe features of ASD compared to 20 years ago. This reflects the inclusion of a more diverse set of people with autism, however, those on the more profoundly affected end may not see the benefits of research that predominantly includes those with completely different features of ASD. One solution proffered to rectify this challenge has been to stratify individuals with ASD into different groups for the purposes of research. Although advocates report that stratification lends itself to precisely determining the needs of specific groups and individuals, other researchers continue to cluster individuals into one group. Whether to stratify or cluster is a prominent discussion amongst scientists and advocates and could become polarizing, as both approaches affect research, basic nomenclature, services such as housing and employment and support services.

1. Features in infancy predict adult outcomes.

Multiple studies this year have linked children’s symptoms and biology in infancy to later outcomes. Motor abilities, family history, brain connectivity all can independently contribute to how a child develops over time. These outcomes include an autism diagnosis, verbal ability, and cognition in adulthood. This sort of research can be used to help prepare families and customize interventions that focus on the most debilitating symptoms of ASD.

This year, to make predictions about future ASD features, more studies used a longitudinal study design. This design is critical to autism research because it follows a group comprised of individuals diagnosed with ASD and, at times, individuals without a diagnosis in order to determine how they are affected as adolescents and adults. Whereas a longitudinal study can be expensive, complex and does not produce immediate results, the nature of its design provides clinicians invaluable data, affording deeper insights that allow them to more fully educate families by managing expectations, identifying focus areas and providing coping strategies that serve to help those with ASD live their best lives.

Longitudinal studies help parents understand their child’s reality and manage future expectations, as well as help scientists refine interventions according to the variability of groups of people with ASD. Multiple research studies have used data to group children based on trajectory, i.e. the progression from commencement, through adolescent development to adult functioning. The composition of these groups consists of those who show fewer symptoms and continue to improve vs. those less functioning who continue to decline. This year, two longitudinal studies, one conducted in the United States and one in Canada, closely examined toddlers to pinpoint and study specific factors that influence outcomes, from childhood to adulthood. In these studies, two patterns emerged: those possessing lower levels of symptoms who improve vs. those with more profound symptoms who decline.

While all groups showed improvement in daily living skills, those who presented less severe symptoms in toddlerhood and showed marked progression during adolescence also had the highest adaptive abilities as adults. Although most participants showed improvement in social communication with age, improvement varied, based on individual language ability as toddlers. Social communication impairments in 19 year olds was found to correlate with differences in language ability as early as age two. As speech improved, so did this core symptom of ASD: those with early minimal language ability showed the greatest functioning impairments as adults. Likewise, fine motor skills in infancy is a predictor of language at age 19, in that better fine motor skills in early childhood is a predictor of better command of language in adulthood. Together, these findings demonstrate that poor early motor skills and decreased language function are related to later ASD symptoms. This is a crucial identification, considering that both fine motor skills and language are target areas of early intervention and that intervention may improve ASD through adulthood.

The study of early motor function is not only vital to further understanding how it affects those diagnosed, it also offers insight pre-diagnosis in terms of how early motor function may predict a later ASD diagnosis. The Baby Siblings Research Consortium (BSRC) is a group of researchers that studies initial features of ASD in siblings of children with ASD as young as 6 weeks of age. Siblings of children with ASD have a 15x greater probability of having ASD themselves than do other children. Similar to previously mentioned studies, BSRC also concludes that fine motor abilities at 6 months can predict an ASD diagnosis in siblings and expressive language ability in younger siblings at 3 years.

Another factor BSRC researchers have employed to estimate the probability of diagnosis in children is number of siblings previously diagnosed with ASD. Those with at least 2 older siblings with ASD were found to have a higher probability of a diagnosis, as well as increased severe cognitive disabilities. Based on family history, this information is vital in helping families better understand the probability of an ASD diagnosis in future children, as well as predicting strengths and limitations future children may face.

In addition to identifying behavioral markers, the past decade of research has revealed a blossoming of early biological factors that may serve as additional predictors of diagnosis, ranging from genetic tests, salivary hormone markers and other reflections of altered development. Studies of brain structure, activity and connectivity have also proven valuable; when measured non-invasively, identified changes in activity in the frontal lobe of the brain during the first year of life have served to predict an ASD diagnosis in infant siblings. Because brain wavelengths vary, identifying and monitoring changes in the size of each different type of wavelength over the course of a year serves as valuable information in terms of not just determining an ASD diagnosis but also for further understanding brain fluctuations during that time period.

Complementary to brain activity, previous studies from the Infant Brain Imaging Network (IBIS) revealed different approaches to more accurately predicting ASD diagnosis by using measurements of brain structure and connectivity, in addition to mathematical algorithms based on the shape and function of different brain regions, as potential predictors of a later diagnosis. This year, the analysis of early brain based ASD markers has afforded scientists more precision in determining an association with brain connectivity in critical ASD brain regions, as well as an insistence on sameness and stereotyped behaviors at 12 – 24 months. Not only do these biological based markers aide in predicting later diagnosis and identifying features of ASD within a diagnosis, they have the potential to serve as objective ways to help determine specific interventions, both medical and behavioral.

2. Screening is not perfect, but it is essential

New technologies contribute to greater use of standardized measures in different community settings. At the same time, clinicians and scientists have developed new ways to use common records and tools, resulting in better identification of concerns at even earlier stages. Families and care providers should confidently screen early and often.

Biological based markers hold promise for even earlier detection of features, especially in those with a family history. However, to make predictions about not just a diagnosis but future expectations of needs as well, most care providers, physicians and clinicians rely on behavioral concerns. Right now, most families lack access to EEG machines and MRIs and expensive genetic testing is most often not covered by insurance. The reality of early detection of ASD in 2019 is that it occurs mostly in primary care settings, where physicians help to interpret results for the family. In 2019, the AAP published an update to their 2007 guidelines for screening for autism and it continues to recommend autism-specific screening at 18 and 24 months. Researchers continue to explore new ways to make this tool more accessible via technology, such as electronic tablets, whereas scientists continue to refine and improve accuracy screening tools using machine learning.

One challenge of current screening practices (and in fact, in all of ASD research) is the disparity in screening and screening results amongst distinct racial and ethnic groups. In order to address these differences, scientists are analyzing a variety of approaches fashioned to deal with these disparities and to increase access to screening tools. This includes remotely employing video based tools to capture ASD features to help identify and diagnosis ASD. These video based tools help parents identify signs by providing real life examples of parent-child interactions and by examining existing reports of developmental milestones from electronic medical records, with the goal of identifying early signs of developmental concerns as soon as possible, in as many infants as possible, regardless of race or ethnicity . Doing so will increase early diagnosis, leading to earlier intervention and increased understanding of ASD, self-awareness of symptoms and long-term improvement of services.

3. The lifespan of mental health challenges sparks new intervention possibilities

The high rate of mental health disorders in both children and adults with ASD means that a large percentage of this population and their families are burdened with enormous challenges Training community providers to deliver mental health interventions shows promise for alleviating these comorbidities. Clinicians need to be on the lookout for these psychiatric issues so people with autism receive the much-needed services they deserve.

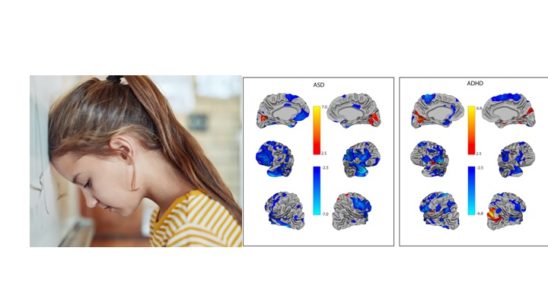

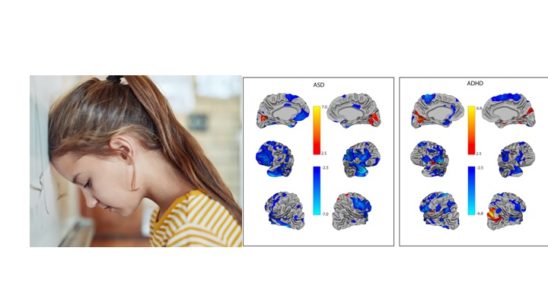

While the core symptoms of ASD often lead to challenges in daily functioning, across the lifetime and spectrum of many individuals with ASD, co-occurring mental health conditions are a huge concern. Several older but smaller international studies provide a wide range of estimates of the prevalence of co-occurring conditions. A met- analysis and systematic review of these studies conducted in 2019 has helped to decipher the findings. The findings revealed 28% comorbidity of ADHD (higher in kids than adults), 20% for anxiety disorders, 11% for depression and 9% for obsessive-compulsive disorder. There is even overlap in brain based profiles of different diagnoses, both in terms of genetic activity and structure. These mental health issues, particularly anxiety, can lead to an acute crisis requiring hospitalization. Unfortunately, clinicians have limited knowledge and understanding of the nature of these mental health conditions in ASD, making intervention difficult. However, ASD researchers have had luck training community mental health providers to deliver interventions focused on addressing these mental health challenges. Training community based providers is a move in a promising direction, allowing more people to receive services in a variety of settings, but the efficacy of these interventions still lags behind those delivered in clinics. Understanding the high co-occurrence of mental health issues helps families and individuals both plan for later health care needs and anticipate potential mental health problems before they occur.

4. Heritable factors that influence brain development result in multiple psychiatric conditions, including autism.

Researchers have determined that of the over 100 autism genes that exist, all act on early developmental functions and lead to diverse, overlapping outcomes, including psychiatric disorders, autism, and related conditions. Some genetic influences, while rare, can help define the mechanisms that lead to brain cells in autism developing over time. Although a link has been established connecting environmental influences to this same spectrum of conditions, few studies have successfully defined their interaction. These findings have implications for interventions and could lead to strategies for mitigating symptoms.

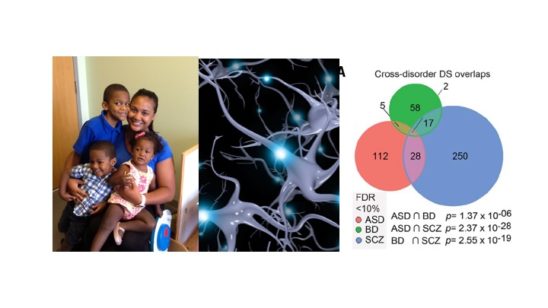

Given the comorbidity of mental health disorders with autism spectrum disorder, it should come as no surprise that new research reveals that ASD relevant genes act in fundamental ways that may influence multiple outcomes, ranging from ASD to schizophrenia, to ADHD, neurodevelopmental disorders and intellectual disability. Genes that act on such early and fundamental brain pathways have downstream effects on a number of brain functions, ASD being one of them. This might explain why there are so many ASD genes and why they are pleiotropic, meaning they have different functions. In fact, the list of genes associated with ASD keeps growing, as larger studies and better technology have revealed over 150 ASD associated genes. Infant siblings of children with autism also show rare and common gene variants in ASD genes that can aid in a diagnosis.

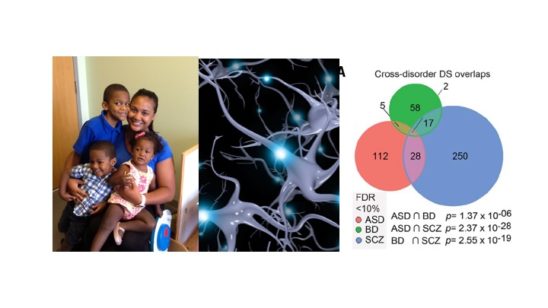

In addition, the presence of certain genetic mutations in ASD relevant genes can produce profound disabilities, which alone work to explain an ASD diagnosis. These mutations, referred to as rare genetic variants, are important to the community because their discovery has led to the creation of Patient Advocacy Groups that provide support and resources for focused research, as well as offer pathways to better understanding the basic circuitry of certain ASD behaviors. Scientists are studying these rare genetic forms of ASD to understand all forms of ASD, particularly gene expression in the brain. When compared to studies of the brains of people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, studies of brain tissue in people with ASD reveal overlapping genetic activity in genes that control synaptic signaling, neurotransmitter release, and immune response.. The abnormal immune signaling in the brain might result in cell damage, as evidenced by accumulation of T-cells in brain tissue. Studying the brains of people with ASD is the best way to understand the basic cellular and molecular basis of ASD, and is only possible through families who decide at the most difficult time to make the decision to donate. If you would like to learn more about the Autism BrainNet, which made these studies possible, visit

www.takesbrains.org/signup.

While genetic factors are incredibly important in the diagnosis and presentation of symptoms of ASD, understanding the role of environmental factors in both the diagnosis and presentation of symptoms of ASD is crucial. One of the most studied environmental factors in ASD is exposure to air pollution during pregnancy. This year, ancillary evidence taken from additional locations via different methodologies shows a particular effect for a component in air pollution called PM (particulate matter) 2.5 (2.5 microns). Air pollution exposure may interact with maternal diabetes, which also increases the probability of ASD. Air pollution also seems to influence an ASD diagnosis more strongly in boys. It is important that public health policy address established, scientifically based environmental factors to address even smaller, but preventable, environmental factors.

There have been spurious reports of other environmental factors, but rather than look at factors in isolation, it is crucial to understand how these factors collectively influence brain development and interact with genetic susceptibility, either rare genetic or polygenic influences. Another area of convergence of environmental and genetic factors is epigenetics, often called the “second genome”. The epigenome is a multitude of chemicals and tags on the DNA genome that is responsive to environmental factors that can turn on or turn off DNA expression, as early as when the embryo is formed. ASD risk genes identified in genetic studies can also work epigenetically

. The next generation of research will hopefully focus on understanding the multifactorial influences of an ASD diagnosis, how these factors affect symptoms and influence long term trajectories across neuropsychiatric diagnoses, including ASD.

5. Females with autism present features differently

Females with autism show opposite neurobiological features of autism, while also possessing some of the same core features of ASD. In females, these differences may be found in the way symptoms present or in associated features of ASD. Lack of differentiation clouds important scientific discoveries, which is why treatments and services should be sex specific.

Over the past five years, ASD research has increasingly focused more attention on identifying and understanding how autism manifests in females; this includes, but is not limited, to: genetic makeup, symptom presentation, long term trajectory and mental health issues. Females are diagnosed 4x less often but also have an increased load of genetic mutations, including recessive mutations. This year, results of studies have been mixed in terms of the magnitude and nature of sex and gender related symptom presentation in males vs. females, noting a problem plaguing ASD research mentioned earlier: heterogeneity. Differences across sex and gender are not seen in terms of presence or absence of symptoms, but rather in the way they present across different ages. On the whole, differences are few in infants and toddlers but are magnified during adolescence, even in the way people perceive ASD symptoms in males and females. Some scientists suggest that associated symptoms are most likely to present differently than core symptoms of ASD, with females showing a higher prevalence of ADHD and OCD, leading to differences in the way males and females appear.

In addition to findings of increased numbers of recessive mutations in the genome of females, analysis of brain structure has revealed sex differences further suggestive of the female protective effect. Focused study of the cerebellum has revealed that female activation patterns oppose those of males with ASD and fail to evince similar patterns of connectivity across different brain regions, i.e. females with ASD show reduced connectivity compared to females without ASD, an effect not seen in males with ASD. In addition, when comparing twins, females had more profound differences in the sizes of brain regions compared to males. These findings have led researchers to refine how they examine the role gender plays in basic science research.

Animal model research suggests that environmental exposures may not produce the same impairments in male vs. female offspring. Taken together, these biological findings demonstrate that females, despite demonstrating a lower prevalence of ASD, also show complicated behavioral features and more biological markers for ASD. Future research must focus on why females are diagnosed less often than males and why, when they are diagnosed, they present more behavioral markers than their male counterparts.

6. It takes a village to make interventions work in the classroom

Teachers play a considerable role in identifying and helping kids across the spectrum, which is why teachers need focused training and support in order to best serve students with ASD.

Teachers and school administrators must perform a multitude of duties and responsibilities in an effort to meet the needs of students of varying abilities within the same classroom and provide all students – those on the spectrum and those who are not – with an equal opportunity to learn. In a perfect world, each student in our school systems would receive exactly what he or she needs, when it is needed, regardless of school systems and across different symptom presentation. Unfortunately, in 2019, researchers documented that in some states, the diagnosis of ASD does not necessarily correspond to the educational classification, an inconsistency which might create disparities in service utilization across states, particularly considering that the quality of programs in many school systems rate just above adequate60.

Adding to these challenges in schools, research shows that students with ASD who exhibit unclear symptom presentation are likely to receive different services. Teacher perception of what is effective often dictates what kind of evidence-based interventions are used in the school system. Therefore, the specific types of support services students need in order to be successful often do not match up to what they actually receive. Studying clinic-based interventions in real world settings, such as in schools, is challenging as well. The biggest problem is that these interventions don’t always translate fluidly from clinic to classroom and often require modifications just to get them into the classroom. For example, according to research, a popular curriculum called TeachTown, commonly used by classroom teachers, does not necessarily help kids with ASD. The good news is scientists are using opportunities like recess65 for social interventions in ASD.

Of real concern is that the types of educational based interventions can vary based on ethnic group, leading to inequity in services. While racial and ethnic disparities continue to exist, researchers are exploring different methods to alleviate these differences. While Medicaid waivers have been shown to be somewhat helpful, most research so far has focused more on defining the problem, so that future studies can be set up to address these challenges directly. Transition to employment in the school system can be improved by the perspectives of those that have successes and challenges with employment. This includes starting early and help build environmental supports for future success on the job. These findings will lead to more tailored and effective intervention strategies to improve services for all people across the spectrum in schools, where they are desperately needed.

7. Model systems of autism are used to understand the earliest, fundamental features of ASD.

Scientists use animals and cells to determine what happens at the onset of autism and when it happens, beginning with the moment the cells are formed, in order to better build interventions for different times in development.

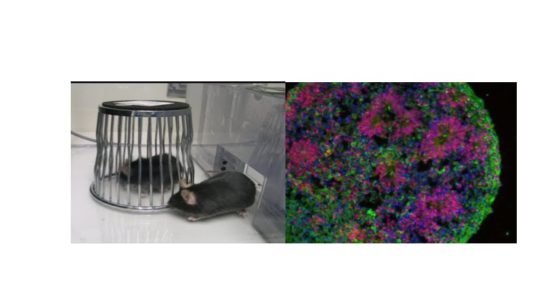

Animals do not have ASD. Cells in a dish do not have ASD. But animals and cells can still provide important insight into not just therapeutic targets but can also offer a comprehensive understanding on what is happening in the brains and bodies of people with ASD. The cells in a dish actually come from cells in a person, including those with idiopathic and rare genetic forms of ASD. By using induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technologies to transform a skin cell into a brain cell and then back into a skin cell, important discoveries about individual brain development can emerge. These models have revealed that certain genes cause neurons to be overconnected69 while others can impair the strengths of those connections or reduce neuronal activity on the cellular level. These are the basic fundamental properties of cell development that seem to be common across multiple psychiatric conditions, including autism.

In turn, animal models allow for a more complex analysis of single genes in the presence of organisms with other genes. Together with findings in brain tissue, these animal models have shown that, despite the gene involved, there are converging networks that could be the target of future interventions. Animal models can also demonstrate which gene x environment interactions exacerbate symptoms or alleviate symptoms in a controlled setting. They have also been able to identify the underlying molecular mechanisms of genetic mutations associated with ASD. Beyond the brain, these new models can identify mechanisms of associated dysfunction like gastrointestinal function which plague many families with ASD. A new technology introduced last year called CRISPR allows researchers to better target genes one at a time or in combination to better understand the roles of genes as well as gene x environment interactions on basic functioning of cells across the body and what this means for humans, helping them both understand and anticipate specific symptoms across time.

8. While scientists now know more about interventions, there is much that they still need to learn.

While the efficacy of fluoxetine for repetitive behaviors has been addressed, other treatments such as fecal transplants, stem cell transplants and cannabidiol still lack an evidence base and therefore use is not recommended at this time. The autism community should be cautious of interventions that lack strong scientific research, as well as by wary of flashy headlines.

This year, advances in behavioral interventions for ASD revealed a common theme: remote delivery. This includes development of telehealth methods and videoconferencing. As mentioned earlier, this methodology will expand coverage while striving to ensure quality. However, findings also demonstrated what does not work. For example, fluoxetine, or Prozac, has proved to be ineffective for repetitive behaviors in ASD however that does not mean people should go off of their medication if it is helping them in other areas, but instead they should be aware that it may not help the core symptoms of ASD. On the other hand, new research in other drug targets, including the vasopressin receptor, showed promise in males. While more work needs to be done, scientists have a better understanding of what works for particular symptoms in specific people.

Although much is known, there is a great need to acknowledge emerging fields where little is known, especially in the field of intervention. Media reports hyping the effectiveness of stem cell studies and fecal transplants pushed these alternative treatments into public view however, the designs were subject to bias or had small sample sizes, suggesting further caution when considering these alternative, non-evidence based approaches. On the other hand, the target of the fecal transplants, the microbiome, has been understudied in basic and clinical studies. Probiotics have also led to improvements in gastrointestinal function in people with ASD, providing evidence that the microbiome is important but needs further study, both in determining mechanism in model systems and more precise intervention therapies.

Another alternative therapy used by families with no substantial scientific evidence is medical marijuana, including the psychoactive component THC and a non-psychoactive chemical within the cannabis plant called CBD. Unfortunately, again, media hype and marketing strategies have provided hope where scientific evidence is lacking. Research in this area is hampered by legal and administrative policies, but newer, more definitive research studies are in progress. While there is reason to be hopeful in this area, there is also reason to be cautious. People with ASD respond differently to CBD than those without ASD, and parents should not assume what works in one child without ASD will work in their child with ASD.

The Autism Science Foundation recognizes that there is much scientific information available from multiple sources that can be accessed on multiple platforms. This summary is meant to highlight this year’s advances, including differences that have changed over time and across sex, as well as shed light on similarities with other neuropsychiatric disorders. It is hard for anyone to make sense of it all when it is announced, or even as these discoveries build on each other. However, it’s important to know that advancements in understanding the basic biology of ASD have led to more specific interventions, increased knowledge of what works and what does work, further expansion in utility across settings and lastly, clues for future studies. Although this summary does not capture every insight and advancement revealed in scientific studies of ASD this year, ASF feels that these highlights offer a comprehensive overview and it will continue to share science news throughout 2020, particularly what is most valuable in helping family members understand how to best serve loved ones with ASD and themselves.

https://autismsciencefoundation.org...ch-2019-the-year-of-preparing-for-the-future/