mr peabody

Bluelight Crew

What one man learned when he treated his autism symptoms with psilocybin

by Jesse Noakes | VICE | 20 Dec 2018

"That trip was like an '80s movie starring me. I saw what my life could be like, without computers and all that rubbish. It gave me the most hope I've ever known."

The morning after his first big trip with psilocybin truffles, Alyx came downstairs beaming and looked his support worker straight in the eyes. In the seven years Claire had been working with him, he'd never been able to meet her gaze before. It was why he'd come to Amsterdam to take psychedelics.

Diagnosed with autism at age five, Alyx, who is 26 now, had been largely housebound since leaving high school near Oxford, in the UK. His social anxiety was so bad that he couldn't talk to the customers for his small computer repair business, so his mother handled them while Alyx only dealt with the machines. The rest of the time he was gaming, up to twelve hours a day. "I spent my whole life isolated and alone," he tells me. "I'd wake up, run computer stuff all day, game, go to bed, and then do the same thing the next day. I didn't realize I was stuck in that loop."

Alyx also found it impossible to speak to people, to talk on the phone, to leave the house by himself. He couldn't look at his mother, he had acute anxiety, he spent 12-16 hours a day, every day, online. He was in specialist schools until he got himself kicked out deliberately at 16. Alyx also, as he tells me, couldn't understand or experience emotions clearly, found body language inscrutable, didn't understand subtext such as sarcasm.

Then, towards the end of 2016, Alyx read a couple of stories about psychedelics and autism, in an article about a clinical trial of MDMA, and a guy on Reddit who said magic mushrooms had helped immensely with his social anxiety, which filled him with hope. "I told Claire, 'okay, we have to go to Amsterdam, because it's the only place they're legal, and we have to take magic mushrooms' and we did."

Actually, they used truffles. Legal in the Netherlands, they are the root system of the mushrooms, and Claire was there purely to support Alyx while he tripped (she owns and runs a company providing support to people with autism), taking a big professional risk. Neither want to use their last name as a result. They spent months researching the ins and outs of psychedelic therapy, and found that there was a fairly simple protocol developed in clinical trials. Two substances, MDMA (the recreational drug most commonly known as Molly or ecstasy), and the psilocybin (the psychedelic substance) in magic mushrooms, share similar therapeutic traits, says Ben Sessa, a clinical psychiatrist who has researched the two substances at Imperial College, London. "They are both equally, interchangeably useful," he says.

In the recently published MDMA study Alyx read about, 12 participants on the autism spectrum had two all-day sessions, with either MDMA or a placebo, in a comfortable therapy room with music, art, and flowers. If they wanted to talk, or dance, they could do that with the two therapists who were with them throughout; if they wanted to kick back with the headphones and see where their minds went, that was all good too. There were regular therapy sessions before, between and afterwards to make sense and meaning of their drug experiences.

The study was tiny, more a proof-of-concept than anything, but the results were promising. For the eight autistic participants given two sessions with 75 mg, 100 mg or 125 mg of MDMA, social anxiety levels reduced by 50 percent. Significantly, they stayed this way when measured again six months later. The placebo group had much smaller reductions as measured by the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (a system created by a psychiatrist to assess what role social anxiety plays in one's life) until they had further sessions with actual MDMA and saw similar improvements.

The study was based on the doctoral work of co-investigator Alicia Danforth, who previously worked on a study of psilocybin for anxiety in patients with terminal cancer. She decided to investigate the social experiences of autistic adults taking MDMA recreationally. Of the 100 she surveyed, around 90 reported better social communication and increased empathy and connection.

Danforth acknowledges that her findings are preliminary. "We hope that the good safety profile and encouraging reduction in social anxiety symptoms will inspire funding for new and larger studies," she says. "We're looking forward to sharing what we learned with other researchers."

It's important to note that this type of treatment shouldn't be tried at home without supervision. "This study was done in a controlled clinical setting in conjunction with intense psychotherapy," says Christina Nicolaidis, professor of Social Work at Portland State University and editor of Autism in Adulthood, and unaffiliated with the study. "It should not in any way be taken as a reason to try using MDMA to treat social anxiety outside of a clinical setting," she says. It's an interesting line of inquiry that deserves further research, but there are many steps needed before it can be considered as a potential treatment."

Claire's decision to support Alyx therapeutically, outside of a clinical setting, was incredibly difficult. "Alyx was so set upon doing it by this point, so passionate about it, that I could tell it was something he was going to do with or without me," she tells me. "He was a consenting adult, he'd done his research. I wanted to make sure that if he was going to do it, he'd be as safe as possible." They'd also done some prep work ahead of time and throughout the process: They shared everything with his parents, social workers, and clinical psychologist, who organized a mental capacity assessment for Alyx as a precaution.

The first trip Alyx took, with a small dose of truffles they bought in a smart-shop near their Airbnb in April 2017, dissolved into a four-hour giggling fit. Claire says it was the first time she'd seen him genuinely laugh. "True, emotional, proper laughter. He was so much more animated, and could talk more fluently."

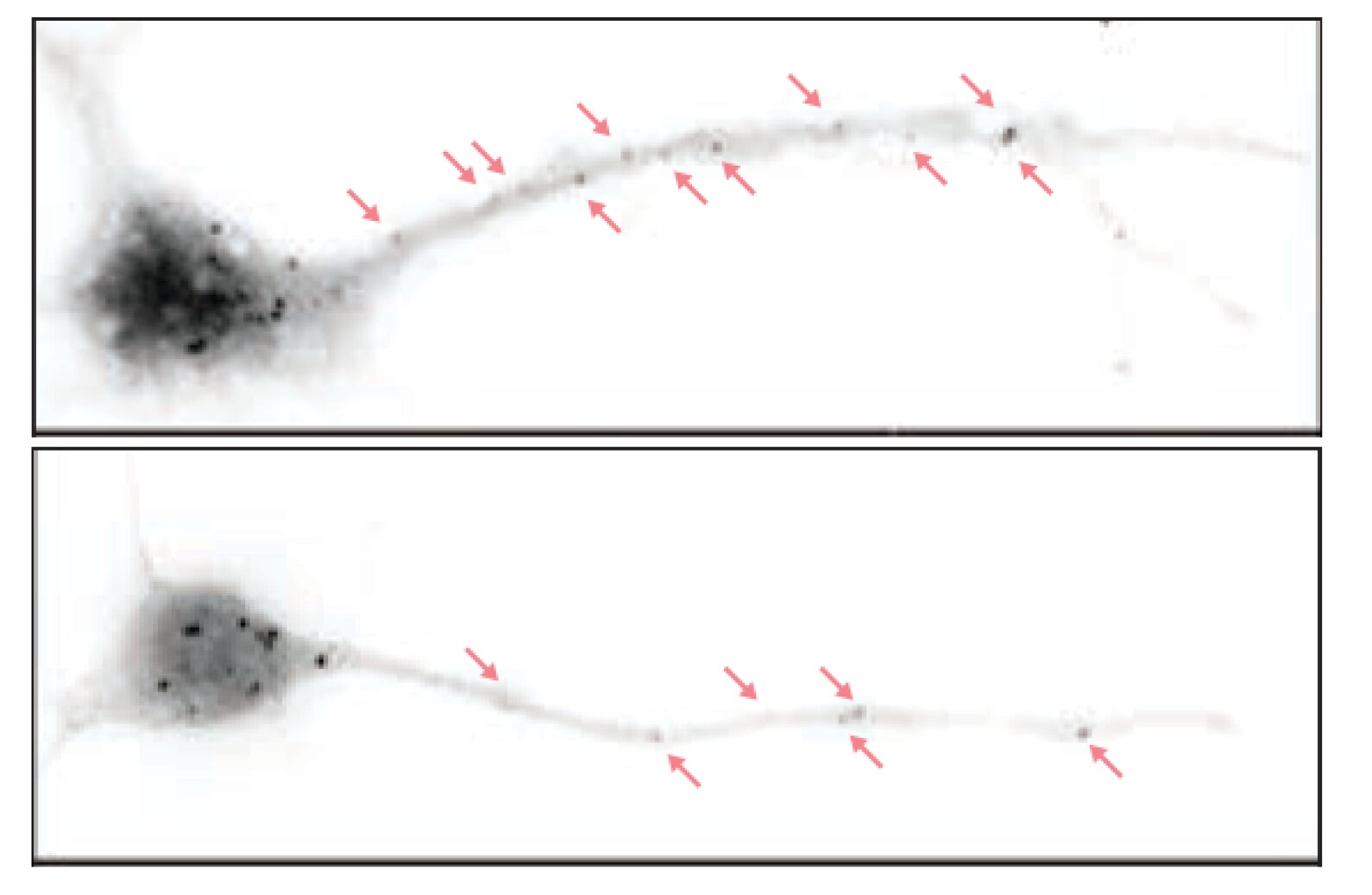

A few weeks later, back in Amsterdam, he tripled the dose to 45 g, which would blow the roof off for most people. Alyx felt like it "it installed the ability to feel emotion." A couple of hours in, he was listening to a movie soundtrack when the emotion in the music suddenly became available to him, like a switch had been hit. Looking at Claire, he could read the feelings in her face like he'd never been able to before. "It was just tears, for hours, that I was able to do that," he says. "Everything just flowed naturally, and I didn't have to think about it at all."

The important thing is that he could still do it once the trip was over. Claire had spent years trying to help Alyx understand what he called "people stuff," conversational inflection, facial expressions, dual meanings. "He didn't understand emotion at all, and so he didn't have the language to express what he was thinking and feeling," Claire says. "But the psilocybin somehow gave him the skills to do it. He was suddenly able to empathize with other people, and have full conversations."

Clearly, there are differences between Danforth's trial and what Alyx did. For starters, although she has a degree in psychology with a masters in autism, Claire is not a psychotherapist. However, they had the benefit of a very close relationship forged over years of constant contact. Alyx is adamant that he couldn't have done it without her.

Again, while MDMA and psilocybin are different drugs, there's a large overlap when they're used for therapy, according to Albert Garcia-Romeu, a research associate at Johns Hopkins University who led a study giving psilocybin therapy to smokers, and found that 80 percent had quit six months after the trial ended. "They're different beasts, but I think they can work towards the same end," he says, adding that similar mechanisms include "helping to promote therapeutic rapport, enhancing pro-social feelings, reducing fear and anxiety related with revisiting past trauma, and improving mood."

Sessa, who is leading the latter trial at Bristol University, tells me that the effects of MDMA for his patients have been surprisingly similar to the classic psychedelic experience. "They've all reported more of a kind of mind-blowing peak experience, in which they talk about 'I can see the light, I can see my problems in a new way."

Alyx's peak experience took place in a Delorean park at sunset overlooking a futuristic cityscape. It came after he'd spent an indeterminate length of time in a state of "no self, no environment," your standard ego death. "The best I can say is that the rest of that trip was like an '80s movie starring me. I saw what my life could be like, without computers and all that rubbish. It gave me the most hope I've ever known."

Garcia-Romeu explains how the two sides of Alyx's big trip, the peak experience (a moment or phase of euphoria) and the ego loss (an intense feeling of connection to the world around you), worked together to allow positive change. "Addictions, whether that be online gaming or drug use, are these kind of rigid patterns that we get locked into. The ego loss clears the way to allow the emergence of these insights. In that way they're very much related." Claire sees Alyx's gaming addiction as a coping strategy. "Social interaction was such an awful experience for Alyx, so you can completely see why it was too stressful, too much to process, so he ran his server and had control, so nothing could go wrong."

When he got back home, Alyx decided to set his house in order. The server went, as did the computer detritus that once covered every surface. In came bean bags, lava lamps, and Christmas lights, transforming the room. "I tried to make it as trippy as possible. Before, my whole existence was maintaining that server, every day. I didn't have a concept of anything else... And now, I haven't played an online game in over a year. All I want to do is sit on the sofa, smoke a bong, and chat."

Danforth emphasises to me that MDMA does not "cure autism." It's crucial to her that this message is clear. And for people with less high-functioning autism this is may not have nearly the same effect. Alyx agrees, but says his psychedelic experiences have changed how he views it. "Before the trip, I used to think it was a disease I could never escape, and that I was sort of sub-human or broken," he says. "Now, I know that I've got problems but I'm doing the best I can to work with them and fix them. I can't ever cure it, but I can make it a lot easier to live with."

His personal relationships have changed dramatically. He's gone on vacations with new friends, and at a psychedelic seminar in London he told his story in front of hundreds of onlookers. He's also blogged extensively about his trips. "I'm a totally different person now," he says. "Before this I didn't really exist, and now I actually have a story to tell, I have a reason to live. There's life where there wasn't. I like telling everyone."

https://tonic.vice.com/en_us/articl...n-he-treated-his-autism-symptoms-with-shrooms

Last edited: