Can psychedelics provide relief for the autistic?

by Jasmine Virdi | Psychedelics Today | 5 May 2021

There is a growing community of neurodivergent and autistic folks using psychedelics, but how does it help them? We took a deep look at the growing body of research and anecdotes to find out.

Current estimates have it that between

1-2% of the world’s population is autistic. In addition to higher levels of social anxiety, depression, and ADHD, autistic individuals meet unique challenges as they seek effective therapeutic treatment methods available to them; psychedelic-assisted therapy is now seen as an attractive alternative for this often sidelined and marginalized population.

There are promising signs that indicate psychedelics could help autistic individuals manage social anxiety, recover from trauma, reduce depression and anxiety, as well as work through the unique hurdles on their path. However it may be the case that for people with lower-functioning capabilities, psychedelics might not have nearly the same effect. Despite innumerable anecdotal reports from individuals who have benefited from psychedelics in a multitude of ways, there is still a significant lack of research regarding how psychedelics could be useful for those with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) diagnoses.

What is autism?

Before delving into how psychedelics can be helpful for autistic individuals, it is first important to understand what autism actually is. Defining it can be tricky because there is still no agreed upon mechanistic, neurological basis for the condition. Despite this, there is research to suggest that neurodivergent brains exhibit

higher levels of functional connectivity, believed to contribute to the intense sensitivity to sensory input and sense of overwhelm that autistic individuals experience in certain environments.

Moving away from stereotyped definitions of ASD as a social impairment, many believe

sensory processing issues to be at the core of autism. Typically, autistic individuals have hypersensitivity or hyposensitivity to sounds, touch, and lights, among other stimuli. As such, autism is characterized by unique, atypical ways of interacting with and processing information. Even so, everyone inherits their own unique neurocognitive version of autism, and although autistic individuals share basic neurological features as well as a common diagnosis, behaviors and traits can vary dramatically from person-to-person.

T

he Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), defines autism in terms of deficits in social communication and interaction, and repetitive patterns of behavior and/or interests that are present (but not always noticed) in the early developmental period. However, such definitions of autism have led to false stereotypes. Looking at autism through this lens of pathology, scientists have long sought out a “cure.” However, pathologizing autism in this way is both harmful and damaging.

In his book,

NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity, Steve Silberman reflects historically how the controversial roots in early psychology have led to widespread misunderstanding of what autism is, and how our societal failure to embrace neurodiversity has been inherently damaging. Further, Silberman speaks to the fact that embracing neurodiversity can benefit our existence in that neurodivergent individuals are often endowed with unique, specialized ways of seeing the world.

Within psychiatry, autism is classified as a “disorder,” however, in recent years this conception is being actively challenged by advocates of neurodiversity. When

defining autism, Nick Walker, queer autistic scholar and Associate Professor of Somatic Psychology at California Institute of Integral Studies, makes a distinction between what he refers to as the “neurodiversity paradigm” and the “pathology paradigm.” Walker describes the neurodiversity paradigm as a perspective that “recognizes neurodiversity as a naturally-occurring form of human diversity.”

Comparatively, autistics are marginalized through the pathology paradigm, which rests on the assumption that there is only one “right” way to be and that if you stray from the dominant conception of normal there is something wrong with you. He adds,

“In the context of a society designed around the sensory, cognitive, developmental, and social needs of non-autistic individuals, autistic individuals are almost always disabled to some degree.”

Although certain features of autism can be disabling, many of the challenges that autistics face aren’t necessarily related to their diagnosis, but rather, arise from the way in which society treats those who don’t fit the mold of “normal.” Many autistic individuals grow up feeling that their way of inhabiting the world is flawed because they do not conform to certain, socially-conditioned ways of being.

Difficulty meeting certain social expectations often ends in social rejection, stifling autistic individuals’ ability to interact with others. Accordingly, autism is often misrepresented as a social deficit by those who are ignorant of the fact that social difficulties in autistic populations are simply by-products of the heightened intensity of their sensory experience. Through the lens of neurodivergence, autism is a neurotype, and labelling it as a “disorder” reflects a value judgement more than anything else.

Looking into the research on psychedelics and autism

In the early 1960s, when LSD was beginning to be used experimentally in research and psychotherapy, a

series of controversial studies were published around treating young children who were believed to have severe forms of autism and childhood-onset schizophrenia (COS) with LSD. Due to misconceptions surrounding autism, it was previously thought to be closely related to juvenile schizophrenia.

The driving justification for experimenting with a powerful psychoactive substance on children was that all other treatment methods had previously failed. Scientists gave a total of 91 children, aged between six and ten, LSD at differing dosage levels and fluctuating frequencies of administration with different treatment schedules, finding that the most effective results were produced at doses of 100 micrograms given daily or weekly for extended periods of time. Undoubtedly, such a study would be unacceptable to an ethics committee today.

Positive outcomes were reported with the use of LSD, with researchers summarizing the most consistent effects as improved speech, increased emotional responsiveness, frequent laughter, positive mood, and a decrease of compulsive behavior. In one such example, researchers observed that the children “appeared flushed, bright eyed, and unusually interested in the environment.” Despite these promising results, positive outcomes were largely dismissed due to the fact that

the study designs were greatly flawed, and were not as scientifically rigorous as those of today’s standards because they lacked experimental controls.

Since this early research, there have been very few studies that have looked into the clinical uses of psychedelics for autistic populations. One of the first to do so was clinical psychologist and MDMA researcher

Alicia Danforth’s 2013 doctoral dissertation, which explored how autistic adults experience the subjective effects of MDMA. Danforth looked at qualitative data collected via online surveys from 100 autistic individuals who had taken MDMA alongside a comparison group of 50 autistic individuals who were MDMA naïve.

MDMA is sometimes referred to as an “empathogen” or “entactogen” because it is a substance that has the ability to facilitate experiences of increased empathy, oneness, emotional connectivity, and emotional openness. In part, MDMA is able to do this because it

encourages the release of oxytocin, sometimes referred to as “the love hormone,” which is associated with social connection and enhancing responses to positive emotions while decreasing the ability to perceive negative facial cues.

The group who had taken MDMA reported sustained benefits such as improvement in social anxiety and healing from trauma. Most notably after MDMA use, 91% of participants reported increased feelings of empathy and social connectedness, while 86% felt that communication came more easily with the effects lasting two years or longer for 15% of individuals.

Building on the positive trends identified in her dissertation, in 2016

Danforth published a paper detailing the rationale behind and protocol for a pilot study using MDMA-assisted therapy to treat social anxiety in autistic adults.

In 2018, Danforth and her team conducted the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled experiment with psychedelics and autistic adults.

Broadly speaking, social anxiety is characterized by a heightened fear of what others think about you, feeling an intensified fear of scrutiny alongside the avoidance of social interactions.

Research has shown that social anxiety commonly co-occurs with ASD, and part of Danforth’s rationale behind the study was to explore MDMA as a treatment modality for individuals with an increased need.

One of the principal aims of the study was to explore the safety of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for reduction of social fear and avoidance for individuals with ASD, finding no evidence of harm to participants. Although the study was small in size, recruiting only 12 participants, results were promising. Participants took part in two full-day sessions in which they were either given MDMA or a placebo. The study used the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale to measure changes in social anxiety. Subjects who received MDMA showed a significantly greater reduction in social anxiety than the placebo group. Reductions in social anxiety symptoms were long-lasting, still holding true at a 6-month follow-up.

In her work, Danforth is careful to emphasize the fact that MDMA and other psychedelics do not “cure” autism, rather when used in a psychotherapeutic setting, they can help to alleviate social anxiety and manage other concomitant issues prevalent in autistic populations.

Reflecting on the study,

Danforth shared that there were substantial recruitment delays. As anxiety and depression are both common in autistic adults, many participants were ruled out because they were using conventional psychiatric medications such as SSRIs. In addition, many of these adults were often unemployed and living in social isolation, less likely to have access to information about the study.

Beyond this small study,

Danforth also created guidelines to psychedelic practitioners working with neurodivergent individuals on how to be mindful of surroundings so as to create an “autism-friendly” treatment space, such as paying careful attention to lighting and taking extra measures to minimize noise.

Beyond the scope of autism, there is a growing body of research that has sought to examine how psychedelics affect social behaviour more generally. A

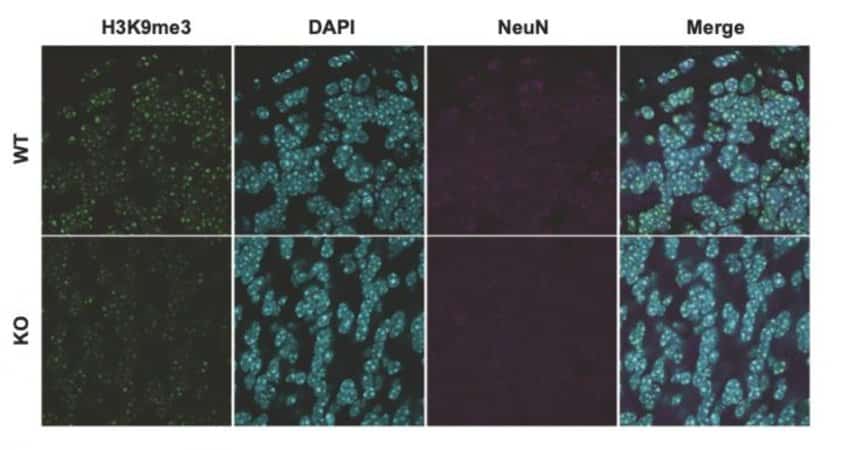

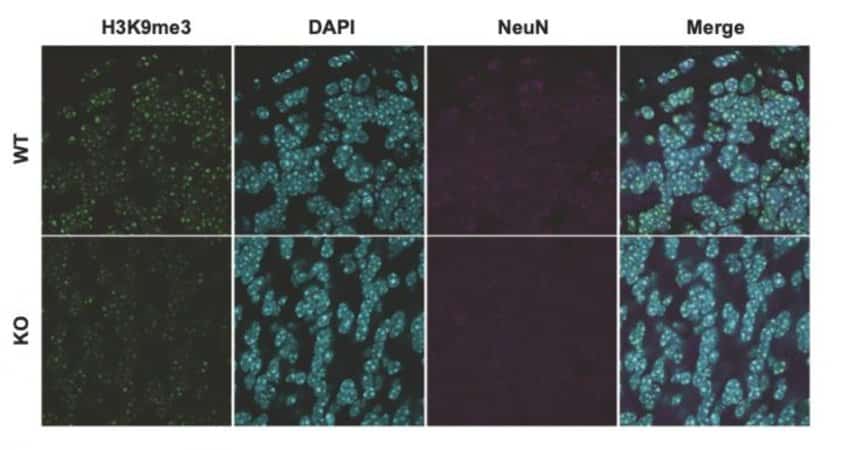

2020 study done by a team of researchers from McGill University examined the effect of LSD on social behavior in mice, whilst measuring their brain activity.

Under the influence of low doses of LSD, the mice became notably more social and friendly towards unfamiliar mice. While it was already known that LSD activates serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, this study illuminated that LSD’s activation of the 2A receptors also triggered a cascade activation of the AMPA receptor and the protein complex mTORC1, working together to encourage social interaction. This is important because

dysregulation of mTORC1 has been linked to autism and social anxiety disorders more generally.

Obviously, behavior and brain function in mice cannot directly be translated to that in humans, however, understanding the foundational mechanism of LSD’s prosocial behavioral effects opens up the door for future research. It also advances the understanding of how the substance could be useful to autistic populations, as well as those that suffer from general social anxiety.

An

earlier study conducted in 2013 also showed that both psilocybin and ketamine altered the way that the brain responds to fearful faces. People under the influence of these two psychedelics were less able to identify negative expressions when presented with images of people with angry or upset expressions.

In the same vein, a

2010 study done with MDMA demonstrated that the substance reduced people’s accuracy in distinguishing negative facial cues. Not only does MDMA enhance emotional openness and connectivity, it also impairs the capacity to notice negative emotions in others’ facial expressions. Similarly,

LSD has been shown to have an effect on emotional processing, enhancing feelings of trust, closeness to others, and emotional empathy, while weakening the ability to detect sad and fearful facial expressions.

In addition,

psilocybin,

LSD, and

MDMA, all work to reduce the activity of the amygdala, a brain region that is associated with emotional processing and stress response.

Brain imaging studies with autistic individuals have shown that the amygdala is differentially activated when presented with anxiety-inducing stimuli compared to the general population.

Psychedelics’ ability to enhance states of social connection and empathy joined with their simultaneous capacity to diminish the detection of negative facial expressions make them a promising therapeutic modality for those that suffer with social anxiety disorders, including autistic individuals.

Even though research into psychedelics and autism is still very limited, we can still draw much insight from psychedelic research into non-autistic individuals and the body of

anecdotal evidence that is growing quickly as more and more neurodivergent people share their healing stories.

The altered state produced by psychedelics helped Orsini better understand how he was prioritizing sensory input, realizing that he had been stuck in a particular mode of seeing and experiencing the world, awakening a deep sense of interoceptiveness.

Interoception is the awareness of what is going on inside one’s own body at any given moment and the ability to take action based on one’s inner experience. For example, noticing dryness in the mouth might serve as an indication that we are thirsty, encouraging us to take action by drinking water. In general, autistic folk tend to have

lower interoceptive awareness when compared with average populations.

“If my body was a car, psychedelics allowed me to realize that my fuel light was low, that I needed food, rest, or felt a certain way,” Orsini says.

“By being able to notice and interpret the cues coming in, I became able to navigate any situation.”

Speaking about his initial experience with psychedelics, Orsini shares,

“ I felt connected to myself, nature, and other people—it was a relief from repetitive thinking, and from there it became the foundation upon which I could rebuild my relationship with myself, my physical and mental wellness, and lead a functional life.”

Orsini draws on the concepts of “

monotropism” and what he calls “polytropism” to explain how psychedelics were able to modulate his consciousness. Monotropism, believed to be a key feature of autism, refers to a cognitive strategy in which one has a narrow set of interests and is only able to focus one’s attention on a limited number of inputs at a given time. On the one hand, monotropic thinking can lend itself to deep thinking and flow states, however, it is also limiting in that information which exists outside of the attention tunnel often gets filtered out, and it can be hard to disengage with a given task or activity when one is so fully absorbed in it.

Comparatively, polytropism designates the proclivity to process multiple inputs at once. Naturally, both types of cognitive processing have their pros and cons, however, when it comes to autistic individuals, polytropic processing is generally harder to access. In Orsini’s experience, LSD was able to occasion a state of polytropic awareness, which he committed himself to working with after his psychedelic experience.

By facilitating novel perceptions, psychedelics could also help autistic individuals learn to embrace their neurocognitive disposition and unique way of inhabiting the world. Many autistic people engage in a behavior referred to as “masking” in which they

camouflage certain challenges by observing and mimicking neurotypical ways of acting in social situations. In some sense, masking is a survival strategy used to conceal behaviors that are felt to be socially unacceptable. Often, masking is the

result of trauma, as individuals feel they need to hide their true selves in order to fit in.

“Autistic behaviors could be patterned off of early life traumas that are likely because of the sensitivity inherent to an autistic individual,” says Orsini.

“I might not have been through war, but I was prone to a more intense sensory experience.”

Independent of neurotype, psychedelics allow for a reappraisal of our default modes of seeing, and a breaking free from the rigid patterns of perception that become habitual. In mental health conditions like

anxiety,

depression, and

OCD, an interconnected group of brain regions referred to as the default mode network (DMN) linked to introspective functions such as self-reflection and self-criticism, tend to be overactive.

Psychedelics have been shown to

dampen the function of the DMN, allowing for a kind of “reset” in the brain in which it becomes easier to separate ourselves from ways of thinking and seeing the world that have become ingrained. If psychedelics are beneficial to the general population in this way, why can’t they also be valuable to autistic folk for the same reason?

To date, there is no evidence to suggest that having an ASD diagnosis is a contraindication for psychedelic use.

“In general, whether it is in a research or retreat setting, there is less certainty on how to navigate autism and so it is often sidelined,” says Orsini.

“However, there is nothing obvious about autism that makes it a contraindication or makes it less safe to explore these toolsets.”

Unfortunately, more often than not, larger subsets of the population get attention first, and according to the

World Health Organization, a whopping 264 million people worldwide suffer from depression. Comparatively, autistics make up a minority population that often gets overshadowed.

Expressing his hopes for future psychedelic research, Orsini shares,

“What I’d like to see is keeping autistics in the conversation when it comes to their ongoing access, and keep them in the domain of people that are considered for early clinical trials.” Additionally, when psychedelic-assisted therapy becomes legalized throughout the US, just as it has

in Oregon, Orsini hopes that medical or retreat centers don’t exclude autistic people.

A future therapeutic modality for autistics: Psychedelic-Assisted Immersion Therapy

Based on his extensive self-experimentation with LSD, Orsini proposed a model therapeutic approach for navigating neurodivergence with psychedelics called: “LSD-assisted immersion therapy.” Immersion therapy is different from conventional psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy in that it is formulated with the idea of facilitating social and interpersonal learning as opposed to a purely inwardly-directed experience. In this context, Orsini suggests that a moderate dose of the substance is preferable so as not to elicit a full blown mystical experience.

Moving beyond a therapist dyad, LSD-assisted immersion therapy, or more generally psychedelic-assisted immersion therapy, involves ingesting the substance in a group setting.

“If I was to have this LSD, and simply reflect on my social challenges in isolation, I may come to an intellectual conclusion, but it is not the same as actually being involved with other people,” says Orsini.

“I envision a future setting in which individuals who are seeking to work on interpersonal issues and skills would be able to do so in the comfort of other individuals who are equally familiar with them,” says Orsini.

“These issues have to do with one’s personal self inventory, but there is a natural therapeutic component to engaging with others in an enhanced state.”

Experiencing challenge around social interaction isn’t specific to autistic individuals, and psychedelic-assisted immersion therapy, or simply

psychedelic group therapy, has the potential to help a wide range of people. Current clinical studies into the therapeutic potentials of psychedelics often overlook an important dimension of real-life psychedelic use, namely, the social dimension.

To some extent, psychedelic insights can be like training wheels on a bike. Once a person is able to access a specific way of thinking in the psychedelic state, it becomes much easier to cultivate the same state in day-to-day life. In the case of autism, people might feel more confident and empowered in daily life, finding comfort in the level of social connection that they were able to achieve in the psychedelic state.

Although pushing for the legalization and acceptance of psychedelics through the lens of medicalization is somewhat of a necessity, there is an inherent problem-solving dynamic that emerges in which psychedelics are viewed exclusively as tools that are effective in treating given issues. However, looking at psychedelics through the lens of neurodiversity, they need not be used to target a given concomitant issues associated with autism, rather they can simply help people understand and embrace their differences. Healing happens when we can move beyond a narrow view of how society should be and encourage people to flourish as they are, instead of attempting to make everyone conform.

There is a growing community of autistic folks using psychedelics, but how does it help them? We took a deep look at psychedelics and autism to find out.

www.psychedelicstoday.com