Bill Wilson, LSD and the Secret Psychedelic History of AA

by Don Lattin | LUCID News | 20 Oct 2020

Taking one mind-altering drug to free oneself from addiction to another mind-altering drug may sound counter-intuitive. But, like with all things psychedelic, this therapeutic approach is all about set and setting, intention and integration, what kind of drugs are consumed, how often and at what dose.

Those who preach that the only way to achieve lasting sobriety is through total abstinence from alcohol and all other drugs may be surprised to learn that the supposed patron saint of abstinence, Bill Wilson, the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, was a firm believer in the ability of LSD to free some hardcore alcoholics from their addiction.

Bill Wilson’s enthusiasm for LSD as a tool in twelve-step work is best expressed in his correspondence in 1961 with the famous Swiss psychologist Carl Jung.

Jung was discussing how he agreed with Wilson that some diehard alcoholics must have a spiritual awakening to overcome their addiction. He pointed out that the Latin word for alcohol is

spiritus.

“You use the same word for the highest religious experience,” Jung wrote,

“as for the most depraving poison.”

That letter of January 30, 1961 — in response to a long letter Wilson wrote to Jung — is fairly famous in AA circles. But in researching my book

Distilled Spirits — Getting High, then Sober, with a Famous Writer, a Forgotten Philosopher and a Hopeless Drunk, I discovered a second Wilson letter to Jung. In that letter of March 29, 1961, Wilson writes at length about his experiments using LSD to help members of Alcoholics Anonymous have the spiritual awakening that is central to the twelve-step program of recovery.

“Some of my AA friends and I have taken the material (LSD) frequently and with much benefit,” Wilson told Jung, adding that

"the powerful psychedelic drug sparks a great broadening and deepening and heightening of consciousness.”

Wilson told Jung that his first LSD trip in 1956 reminded him of a mystical revelation he had after hitting bottom in the 1930s and winding up in a New York City hospital ward for hardcore alcoholics.

“My original spontaneous spiritual experience of twenty-five years before was enacted with wonderful splendor and conviction,” he wrote.

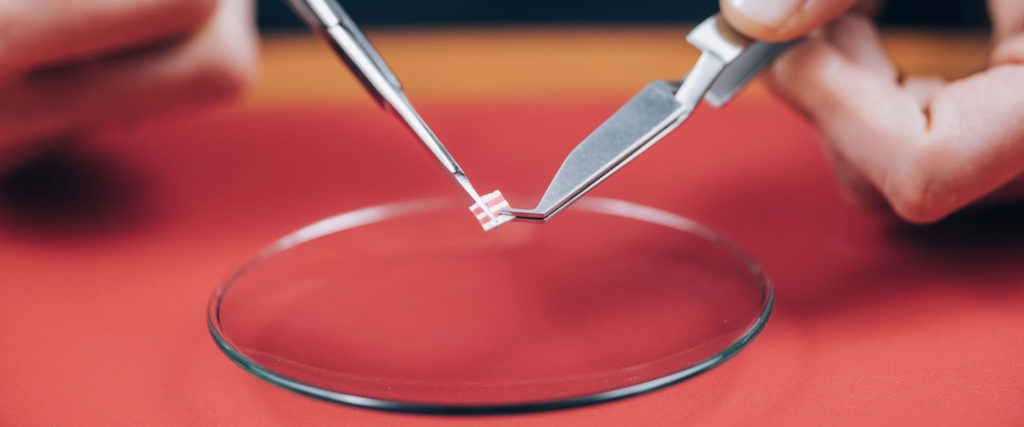

LSD was still legal in 1956, and in Wilson’s case initially taken under the medical supervision of UCLA researcher Sidney Cohen, and with the spiritual guidance of his Wilson’s friend, Gerald Heard, an Anglo-Irish mystic and early proponent of psychedelic spirituality. Wilson would go on to quietly form a bi-coastal psychedelic salon with various leading lights of that decade, including the writer Aldous Huxley.

Wilson’s earlier spiritual experience occurred in December of 1934, before LSD was even invented. It happened during Wilson’s fourth and final stay at a private New York City hospital that employed something called the Towns-Lambert Cure to treat their alcoholic clients. Many of these patients, including Wilson, were once-successful businessmen whose drinking had spun out of control during the Great Depression.

“Suddenly,” Bill would later recall,

“my room blazed with an indescribably white light. I was seized with an ecstasy beyond description.”

That room was in a rehab center where doctors employed a potion which included two drugs derived from plants known to cause delirium and hallucinations. One of them is belladonna and the other henbane, was long associated with witchcraft and potions said to summon the spirits of the dead. (Warning to psychonaunts: both of these plants can be poisonous at high doses.)

So there’s a good chance that psychoactive plants played a role in what came to be known as the founding vision of Alcoholics Anonymous, even though the effects of the herbs used at Towns Hospital differ from other psychedelic plants and from the LSD Wilson would begin experimenting with two decades later.

Here’s how Bill W. would later describe his Towns Hospital vision:

“In the mind’s eye, there was a mountain. I stood upon its summit where a great wind blew. A wind, not of air, but of spirit. In great, clean strength it blew right through me. Then came the blazing thought, ‘You are a free man.’ ”

In my view, it doesn’t really matter if Bill’s vision was caused by psychoactive plants, divine revelation, or the hallucinations hardcore drunks sometimes experience when they hit bottom and stop drinking.

What matters is that the vision transformed his life and inspired a crusade to free other alcoholics from addiction.

One of the foundations of the twelve-step recovery program Wilson and company devised in the 1930s is the proposition that alcoholics and other addicts must undergo a “spiritual awakening” inspiring them to “turn our will and our lives over to the care of God

as we understand Him.”

Those are the only words in the twelve steps that were printed in italics, indicating an openness in the early AA circles to finding God in the Judeo-Christian tradition, Eastern spirituality or, twenty years later, in a tab of acid. In fact, long before he discovered psychedelics, Wilson was a serious student of paranormal psychology and various forms of spiritualism, holding seances and other gatherings with some of the leading psychics of his time.

In his second letter to Jung, Bill Wilson told Jung that

"many members of AA have returned to the churches, almost always with fine results. But some of us have taken less orthodox paths. Along with a number of friends, I find myself among the later.”

Wilson cited the Canadian research of Humphry Osmond, the man who turned Huxley onto mescaline in 1953. Osmond reported that 150 hardcore alcoholics were “preconditioned by LSD and then placed in the surrounding AA groups.”

Over a three-year period, they achieved “startling results” when compared to similar drunks who were not treated with psychedelics, but only got AA.

“My friends believe that LSD temporarily triggers a change in blood chemistry that inhibits or reduces ego thereby enabling more reality to be felt and seen,” Wilson told Jung.

Jung became seriously ill around the time he received Wilson’s second letter. He never answered that missive and he may not have even gotten a chance to read it before he died.

Jung died on June 6, 1961.

Bill Wilson died ten years later from diseases caused by the other addiction he could never shake — cigarettes.

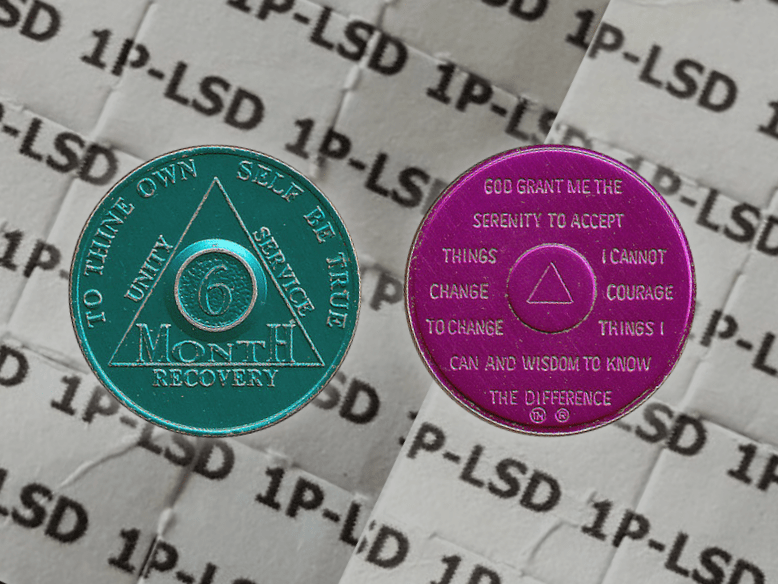

In the end, not much came of Bill Wilson’s idea to introduce LSD into Alcoholics Anonymous. More cautious and conservative elements in the AA fellowship pushed back, questioning their founder’s unbridled enthusiasm for the drug.

In one letter, Wilson asserted that the powerful psychoactive compound was “about as harmless as aspirin.” But in another piece of correspondence, he acknowledged that

"LSD does not have any miraculous property of transforming spiritually and emotionally sick people into healthy ones overnight.” Wilson also wrote that those opposing his LSD enthusiasm in AA were joking that

“Bill takes one pill to see God and another to quiet his nerves.”

Meanwhile, by the mid-1960s, the notorious LSD evangelism of such counter-cultural icons as Harvard Professor Timothy Leary and Merry Prankster Ken Kesey had begun turning mainstream America against the idea of psychedelic therapy.

In recent decades, psychologists and neuroscientists have resurrected substance abuse research that began in the 1950s and was shut down during the “war on drugs” in the 1970s and 1980s. Clinical trials have, once again, shown the effectiveness of using psychedelic drugs, along with psychotherapy, to treat addiction to alcohol, cocaine and tobacco.

At the same time, there has been an explosion of interest in the ritualized use of ayahuasca, ibogaine and other plant medicines to help those addicted to various drugs of abuse.

In my book

Changing Our Minds – Psychedelic Sacraments and the New Psychotherapy, I interviewed addicts, alcoholics, therapists, shamans and scientists doing this work.

Carroll Carlson, an alcoholic treated in a clinical trial at the University of New Mexico, said a vision she had of Jesus during psilocybin-assisted therapy enabled her to “forgive myself for the choices I had made.”

Gordon McGlothlin, a lifelong smoker approaching retirement, kicked his tobacco habit following a psychedelic clinical trial at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Asked how his trip did the trick, he said,

“You suddenly understand how your body and the universe are connected…I might want to have a cigarette, but now I know I don’t need it.”

Carson, a heroin addict I interviewed at a treatment center in Mexico and asked that his last name not be used, was treated with two psychedelic medicines — ibogaine and 5-MeO-DMT. Carson, a 31-year-old evangelical Christian from Dallas, said he felt “reborn” after the experience.

“Since the ibogaine,” he told me,

“the basic craving that I’ve had for opiates is gone for the first time in ten years.”

If this all sounds too good to be true, that’s because it sometimes is. Another heroin addict I interviewed for my book went to this same clinic and quickly relapsed after his miracle cure. He soon realized that he needed an ongoing support group and other lifestyle changes if he was to stay free from addictive thoughts and behaviors.

That’s exactly the point behind an emerging network of alcoholics and other addicts who have slightly rewritten Bill Wilson’s twelve steps and hold Zoom meetings under the banner “

Psychedelics in Recovery.”

As a recovering alcoholic and cocaine addict, I played a minor role in the formation of that online fellowship. I got sober in 2006, and did so without psychedelics. I tell that story in

Distilled Spirits. In 2014, after eight years of taking nothing stronger than a double espresso, I started researching and reporting

Changing Our Minds. Over the next few years, as part of that project and to satisfy my own curiously, I cautiously revived my own psychedelic experimentation. As a participant/observer, I explored the therapeutic and spiritual use of magic mushrooms, MDMA,

ketamine, ayahuasca and 5-Meo-DMT.

So far, I have not touched alcohol and cocaine — nor have I fallen into the abuse of psychedelics. I still drink too much espresso.

Others have not been so lucky. My work with Psychedelics in Recovery showed me how easy it is for addicts like me to fool ourselves and fall back into addictive, abusive and harmful use of drugs that, in a therapeutic or spiritual setting, might help us at least temporarily dissolve the ego and examine our own self-centeredness.

“Defining our own sobriety” may work for some, but certainly not for all addicts and alcoholics. Honesty, openness and truly knowing ourselves, with the help of a supportive community, seems to be the best route to recovery — with or without a psychedelic assist.

Bill Wilson, the co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, was a firm believer in the ability of LSD to free some hardcore alcoholics from their addiction.

www.lucid.news