mr peabody

Bluelight Crew

Psychedelics as Antidepressants

by Austin Lim | Scientific American | 30 Jan 2021

The treatments of the future may arise from a long-stigmatized class of drugs

The first modern antidepressants were originally tuberculosis medications, created from leftover World War II rocket fuel. In 2019, the Federal Drug Administration approved Spravato for depression, a chemical that was originally a veterinary anesthetic and later used recreationally as a club drug.

Why shouldn’t tomorrow’s antidepressants also come from unexpected sources?

Rising COVID infection rates and death tolls lead millions to worry about their own health and safety as well as that of loved ones. These concerns compound daily stressors that can include grief, economic insecurity, job loss, food and housing insecurities—all factors that are contributing to rising suicide rates.

The reliable joyful distractions such as weddings, family gatherings and spontaneous get-togethers are on hold. Unsurprisingly, anxieties combined with decreased human interaction have led otherwise healthy people to depression and a sudden increase in prescriptions of antidepressant medications.

And for some people, these drugs are effective at keeping a person out of their persistent cycle of negative thoughts, a symptom that defines clinical depression. As of 2018, nearly one in eight Americans use antidepressants. Unfortunately, more than a third of patients are resistant to the mood-improving benefits of medicine’s best antidepressant drugs.

These people are not completely out of options, and science is steadily working to find ways to help them. There are chemicals already out there that can restore their mood balance, and in some cases, even save their lives. Unfortunately, these drugs have a name that wrongfully conjures up controversy and alarmist news headlines: hallucinogens.

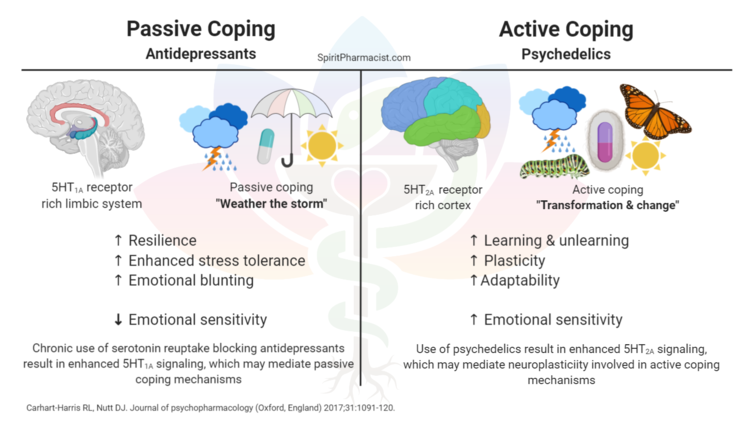

Chemicals such as LSD, psilocybin and DMT are more accurately called “serotonergic psychedelics” among the neuroscience community. Outside of this group however, many people don’t think of these compounds as antidepressants to be distributed by white-coat-wearing psychiatrists. Instead, they imagine whimsical blotter papers passed around by washed-up hippies at Grateful Dead concerts.

And yet, researchers in the U.K. have already been given the green light to begin clinical trials for using DMT for treating depression.

To a neuroscientist whose focus is the striatum, a brain area involved in complex conditions ranging from depression to addiction, it’s evident that these drugs have tremendous promise for a safe, happier future.

Many states are looking to reevaluate the legal status of psychedelics. This is a start at improving the public perception of psychedelic use, which can ultimately encourage more to seek psychedelic therapy in psychiatric practice.

Denver, Oakland and Santa Cruz, Calif., are among the first American cities to legalize psilocybin. The recently approved Measure 110 in Oregon decriminalizes LSD. Legislation has been moving forward in New Jersey, Washington, D.C., and Vermont to downgrade the severity of punishments for possession of psychedelics.

All of these measures represent a reframing that looks at the science of the drug rather than a set of beliefs about the drug.

The stigma against psychedelics could be a result of its status as a controlled substance. Since its criminalization in the 1960s and subsequent vilification by the media, LSD was seen as a public nuisance and enemy. But prior to this, the National Institutes of Health funded more than 130 studies to explore the benefits of psychedelic therapy.

Today, psychedelics still fall into the federal classification of Schedule I drugs, which carry the highest penalties associated with their possession and use. Because of government regulations, controlled substances are difficult to study, even in a clinical setting.

But this hasn’t completely stopped researchers from examining their benefits. Recent studies have arrived at several noteworthy conclusions.

First and foremost is the safety of these drugs. At the correct doses, psychedelics are well tolerated, producing only minor side effects such as transient fear, perception of illusions, nausea/vomiting or headaches. These fleeting side effects pale in comparison to the severity of commonly prescribed antidepressants, which include dangerous changes in heart rate and blood pressure, paradoxical increases in suicidality, and withdrawal symptoms.

As far as outcomes go, psychedelics in combination with psychotherapy are remarkably efficient at treating depression. Compared to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs, the current gold standard in antidepressant medication, psychedelics have a faster effect on patients, sometimes effective with only a single therapy session. On the other hand, anti-depressants often take weeks before a reversal of depression is observed.

Psychedelics also have a longer-lasting effect than an SSRI regimen. A 2015 study of more than 190,000 Americans demonstrated that past history of psychedelic use decreases the odds of suicidal thoughts or actions over the course of a lifetime, whereas a history of other drug use (such as sedatives or inhalants) increases these risks.

Psychedelic therapy may reverse the symptoms of other complex psychiatric conditions. Evidence suggests that anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder and tobacco or alcohol misuse disorder may also be treated with psychedelics.

It is still unclear how much these treatments will cost, but one study predicts that psychedelic therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder could save each patient $100,000 over a 30-year window.

Putting aside preconceptions about these drugs, if objectively comparing their properties to the other drugs that someone can easily buy at a convenience store, their safety becomes apparent.

Psychedelics have extremely low addictive potential. Tobacco is regarded as one of the most addictive substances, ranked just behind heroin and cocaine—not to mention the significant shortages in life span that make tobacco use the number one leading cause of preventable death.

Alcohol use contributes significantly to risk of harm to oneself and others. However, using alcohol and using tobacco products are both widely perceived as socially acceptable. “Why aren’t you drinking?” is a common (yet intrusive and unfair) question in social circles.

They are also very safe compounds with low toxicity profiles. A woman who took a dose of LSD 550 times higher than a typical dose lived without any medical attention; imagine the life-threatening consequences of drinking just five times as much alcohol as normal. (Not only did she survive, but she also noticed a significant reduction in her chronic pain condition, and was able to decrease her usage of morphine as part of her pain management treatment.)

Certainly, people have been injured while taking psychedelics. Most famously, Diane Linkletter, daughter of radio and TV personality Art Linkletter, tragically died by suicide in 1969, presumably while taking LSD. Following her death, Linkletter became a prominent voice in the anti-LSD movement. It is unclear whether LSD led her to suicide, but no drugs were detected in her autopsy report.

Other documented cases include instances of people using psychedelics of questionable purity or in unknown doses, and almost always in conjunction with other drugs.

Psychedelics given in a therapeutic context are pure substances, created by trained chemists and pharmacologists. Dosages are therefore carefully calculated to produce the minimum necessary therapeutic effect.

Equally importantly, these drugs are delivered under close supervision by behavioral psychiatrists who carefully monitor the mindset and the surroundings of the patient. This limits the outside influences that could cause the patient to behave unpredictably, hurting themselves or others.

Psychedelics as Antidepressants

The treatments of the future may arise from a long-stigmatized class of drugs

Last edited: