Tiny amounts of LSD for depression

by Olga Khazan | The Atlantic | 14 Jan 2017

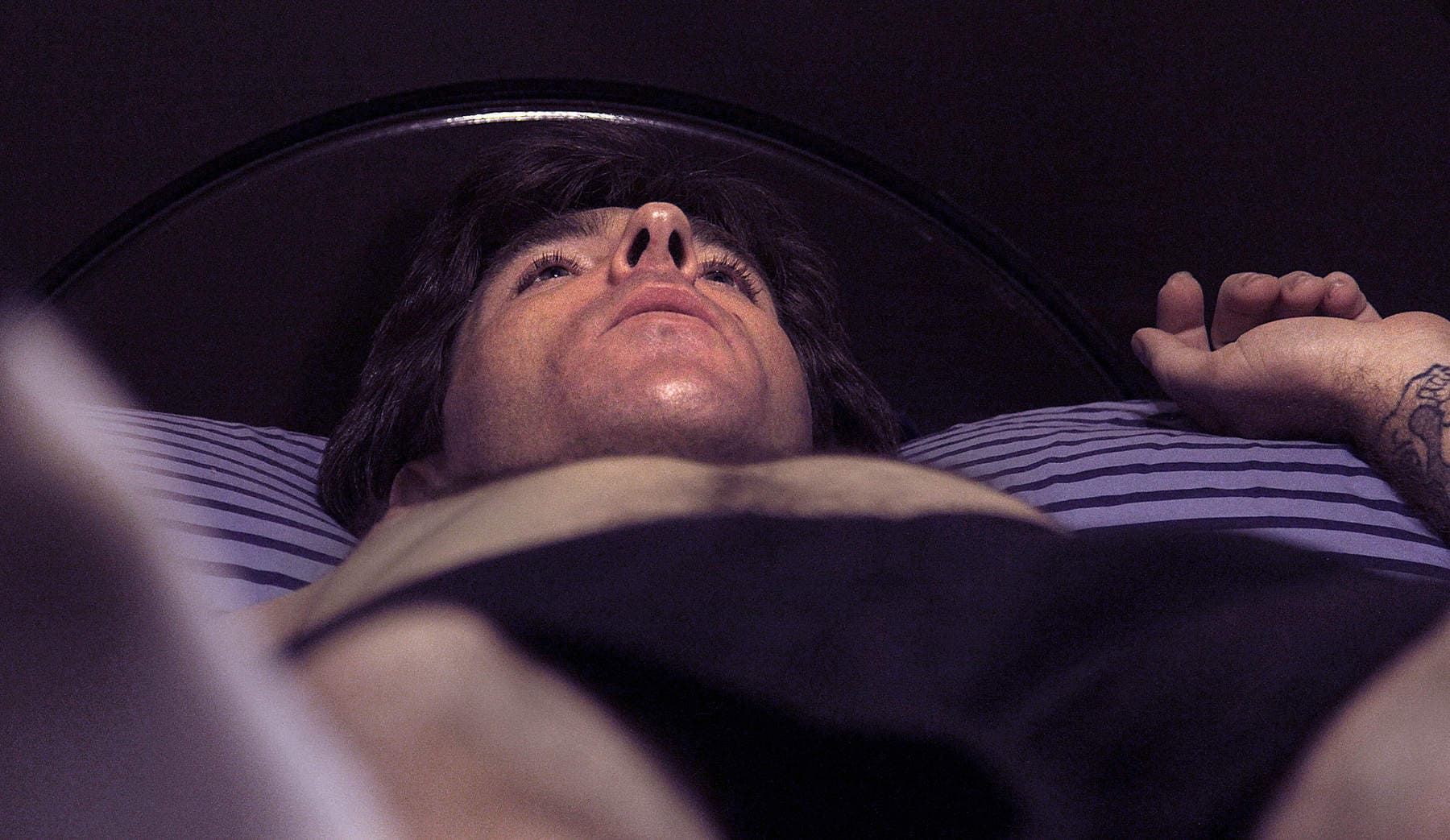

Throughout Ayelet Waldman’s entire life, she’s been

“held hostage by the vagaries of mood,” as she explains in her new book, A Really Good Day. She is a bestselling author, mom of four, and devoted wife, but her mental illness threatened it all. On good days, she was funny, productive, and kind. But on bad ones, she would catastrophize and snap at her family. So profound was her self-loathing at times that, planted on a couples’ therapist’s couch, she couldn’t bring herself to say that her husband, the novelist Michael Chabon, loves her.

A clear diagnosis (was it bipolar II or extreme PMS?), effective treatment (Effexor or Adderall?), and even the fleeting tranquility of a “good day” were all elusive. So Waldman did what few middle-aged American moms—though perhaps quite a few moms living in Berkeley, California—would think to do: Drop acid.

She procured a small, cobalt-blue bottle of diluted LSD from a friend of a friend. It was meant for “microdosing”—taking a fraction of a typical dose every few days, not enough to hallucinate or get high. Instead, the mind opens up just a crack and allows the bleak thoughts to escape for a while. (

“Not so much an acid trip as an acid errand,” she says.)

Waldman begins taking two drops every three days. As the title suggests, over the month her supply lasts, she enjoys several unfrazzled, hyper-aware, “really good” days.

As a relatively drug-averse former attorney, Waldman offers a different perspective from the young tech entrepreneurs who have copped to microdosing to enhance their creativity and output. Her newbie status distinguishes her book, as does the unique way she weaves in digressions about drug policy and the criminal-justice system.

I spoke with Waldman recently about her experience; an edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Olga Khazan: What would you say was the biggest advantage for you of the microdosing, from your mood to your work?

Ayelet Waldman: I think for me personally the most important thing was that it kind of jump-started me out of a pretty significant depression.

Let's say an incident happens, someone says something that hurts your feelings, you see a tweet, whatever it is, some kind of stimulus, there's sort of this four-part process. You see this, there's the incident, you have an emotional reaction, a feeling, then you have a thought about that feeling, then you have a kind of impulse, and you act on the impulse, right?

What has always happened to me is those four separate responses were all sort of clumped together. So I would see something on Twitter, and I would respond right away. There was no time at which I thought, oh you're having a feeling about this, this is making me angry. Is it really making you angry or is it making you sad? Is it making you scared? And then, here's the impulse to act. Is that the right way to really be acting? I would do these things that I would regret, which would, for me, end up catalyzing kind of a depression.

For some reason the LSD microdose sort of slowed me down. I'm sort of trying to figure out 100 different ways to say this other than “mindfulness,” because I find the whole concept sort of aggravating. But I do think it came down to that. I felt happier or at least not as profoundly depressed almost immediately the very first day I took it. God, here I am twisting myself into a knot to not say “mindfulness,” but that really is what it is.

Khazan: You tried a lot of different pills in the past, antidepressants and other drugs. Those are all newer things and they have lots of scientists working on them, testing them, and trying to market them. Why do you think this old psychedelic worked better than all those different drugs?

Waldman: First of all, this is a one-month experiment, and there's no guarantee that it would have continued to work, and there's also no research that what I was experiencing wasn't, as I say in the book, "the mother of all placebo effects."

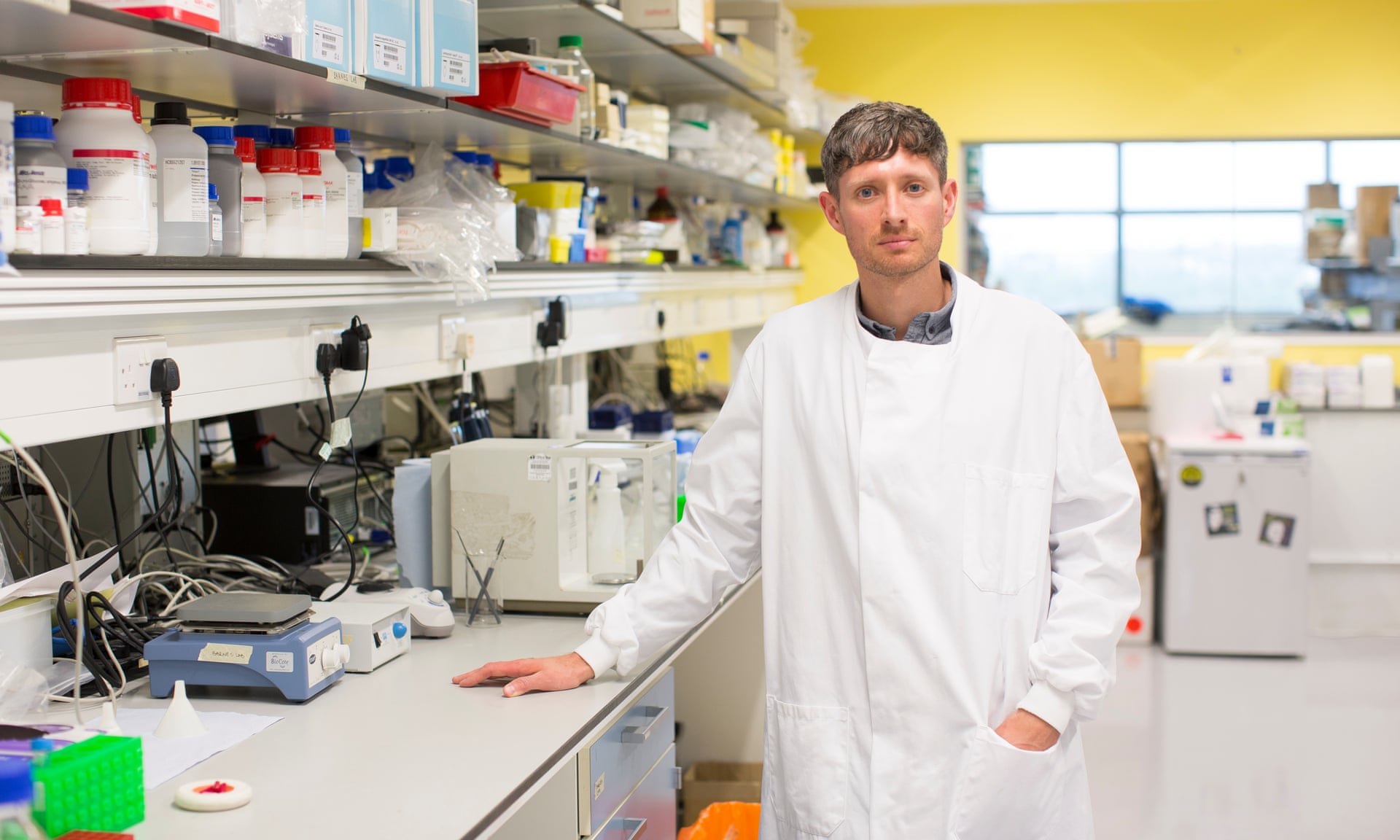

But let's say that it was, let's say that what I experienced taking the microdose was an actual, real effect and not all in my head. I took SSRIs, I took Wellbutrin, I took some of the ADHD drugs, but only very briefly. But they didn’t work to enhance neuroplasticity in the same way that LSD does. My theory is that it has something to do with the neuroplastic effects.

And the range of side effects of all these newer meds is really robust. LSD just doesn't have that many side effects. I mean except the most obvious one, which is if you take too much you start tripping your balls off.

Khazan: One thing I loved about this is you explore other issues in drug policy throughout the book. I was wondering if you could give a couple-sentence layman's-terms summary of why people can't just microdose with LSD. Why is it illegal to acquire even in really small amounts?

Waldman: Very simply, LSD is in Schedule 1. Schedule 1 is a drug that's considered to have no medical use and significant harm. Heroin is on Schedule I, LSD is on Schedule I, marijuana is on Schedule I. You say to yourself that doesn't make any sense. No medical use and significant harm? How is marijuana in the same place on the schedule as heroin? But therein lies the incoherence of American drug laws.

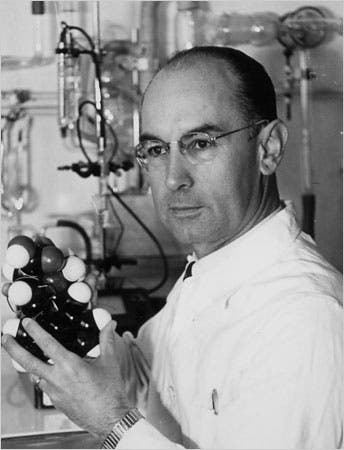

When LSD was invented in the 1930s, it was invented as a medicine, but in the 1960s it basically became a party drug. In the 1960s, the drug was criminalized, and the reason it was criminalized has everything to do with what was going on politically and socially in the country. So when Timothy Leary stands up in front of the massive crowd at the Human Be In at San Francisco and says "Turn On, Tune In, and Drop Out" to a group of basically all young people—and all white young people—that's very important.

They start taking LSD, and more importantly they start protesting the war, and their parents—nice, middle-class, white parents—freak out, and it becomes a scapegoat for this moment of social upheaval and it's thus criminalized. It's interesting because the criminalization of LSD is not like the criminalization of marijuana, the criminalization of cocaine, the criminalization of opium. Those drugs were specifically tied to different minority groups. Marijuana criminalization was a way to attack Mexican Americans, and cocaine was really a way to attack African-Americans.

LSD came from a different place. The idea that your kid would take a drug and start to trip just scared the shit out of everybody, so it became criminalized. And as soon as something is placed on Schedule I, all research grinds to a halt.

Khazan: How are the health risks of microdosing different from regular dosing?

Waldman: When I went into this, I assumed I was going to find all of these terrible things about the health risks of LSD, but if you took a microdose, maybe you could ameliorate those risks.

It turns out actually that there has never been a recorded incident of a fatal overdose of LSD. If I tried to think about what the health risks might be, it's not so much physical, it's not like MDMA, which causes a range of physical side effects. The danger, such as it is, is most closely related to something that was once called LSD psychosis. If you have a hallucinatory experience in an uncomfortable setting, it can be terrifying. The anxiety and the fear of that unpleasant experience can have emotional repercussions, particularly if you're someone with a mental illness.

So that's what I was worried about. Could it trigger some kind of anxiety in me that would be worse than the profound despair I find myself in now?

But the anxiety response is to the hallucination itself and to the feelings engendered by the hallucination, and microdosing isn't hallucinatory at all. And even though I'd read that a million times, I didn’t believe it until I took it. I mean you're taking LSD, aren't the walls gonna breathe?

The only thing that I noticed was it was easier for me to see the beauty in my natural world. I live in Northern California, it's ridiculously beautiful. You walk out my door and there's jasmine everywhere, the smell is overwhelming. And 99.999 percent of the time, I don't even notice. When I was microdosing I would stop and say,

"wow, that is a beautiful redwood tree."

And again, here I am, back in that horrible mindfulness place where I have to use that word.

Khazan: Sometimes it's the only one that fits. Have you listened to the Reply All podcast episode where they microdose and have kind of a bad time?

Waldman: Yeah, I have.

Khazan: What did you think of that, how do you think your experience was different?

Waldman: First of all, here's a little tip: Don't take double the microdose and do something like drive a car on a really tiresome road trip. That seems like a mistake.

First of all, we don't know that what they took was LSD, because they didn’t test it. They also took too much. They were trying to keep it a secret from their colleagues, and that maybe enhanced their own anxiety.

The microdose is a little activating. If you've ever taken Adderall or Ritalin, I think for me it was not dissimilar to that, but much less intense. So I think if you're someone who doesn't normally experience those feelings of activation, then that might be disconcerting and unpleasant.

But, you know, no drug is for everyone.

Khazan: Given your history as a public defender working on drug cases, while you were doing this did you ever get paranoid and think "I'm gonna get arrested!"

Waldman: I decided that I didn’t want to stop but when my bottle ran out, because I was feeling so much better and I cannot understate how depressed I was. It was the closest I've ever come to being suicidal. I would Google the effects of suicide on younger children and older children, because I have both.

But I do think I would have destroyed my marriage as a kind of suicide because it's so important to me, and because I love my husband so much, and my marriage is such a source of comfort and strength. I think destroying the thing that made me feel the most safe in the world was how I would have effectively committed suicide.

But I woke up and took the dose, and 90 minutes later, the fog lifted. I hadn't felt like that for months and months and months.

So at the end of 30 days, I was like fuck that, I am not going back to that pit. I'm going to go buy drugs.

So I found a person, a number, and I texted the number, and the individual who I called “Lucy” texted me back, and I was all set to go buy drugs. I think I wanted five doses or ten doses, which I thought would carry me for a year.

Khazan: And they were like, “can you buy 60 doses?”

Waldman:

"Yeah, I can't separate it, could you take 60?" And that pumping up the figure is just what happened to every one of my clients [when I was a defense lawyer]. That like,

"I wanna buy a little methamphetamine” ... “oh here take a lot!” That's what you do when you wanna get someone into a mandatory minimum jail sentence.

So I was in my very lovely neighborhood in Berkeley, outside a Lululemon, when I decided that the mighty forces of the DEA had been marshaled to bring down this middle class, middle-aged mom of four.

I ran home and sat in bed and readied myself for incarceration. I was like,

“Alright, you'll be able to read, there's lots to read. You're a lawyer, you can help people, there are a lot of people in jail who need legal help. You can't practice law, but you can surely be like a jailhouse lawyer." I was sitting there figuring out how I was going to turn my period of incarceration into an altruistic enterprise.

I'm constitutionally incapable of buying illegal drugs. I've just never bought any illegal drugs. Anything I've ever taken has just been given to me.

Khazan: The kind of shady nature of this, I think, does discourage people from trying it because it's not fun to try to acquire.

Waldman: It's so shady. It's true. The big thing I say to my kids, every time I say goodbye to them is "use a condom, test your molly." Because I really believe that one of the most problematic side effects of criminalization is no one knows what they're taking and especially now when it's so much cheaper and easier for criminal enterprises to create these “alphabetamines,” some of which are incredibly dangerous. Synthetic cannabinoids are just a nightmare. I live in fear that one of my kids is gonna decide they're gonna take molly one night and end up ingesting one of those.

Khazan: Are you still worried about getting into legal trouble, having published this book?

Waldman: I was quite confident that nothing was going to happen. I think it's grandiose to imagine that I am a high priority of Jeff Sessions. That said, we have just elected a president whose attorney general is so retrograde, such a dinosaur in his thinking about the drug war, that anything is possible.

A consensus had formed before this election that the war on drugs was costly and ineffective. And simultaneously with electing Donald Trump and bringing in Jeff Sessions, we also legalized marijuana in a bunch of states. So it's a really schizophrenic moment in history. So yeah, I think it's possible.

Khazan: I noticed that a couple times in the book when you talked about your experiment with people, the reactions were sort of mixed. You almost felt like people were judging you a little bit. Now that it's a little more public and there's a book about it, are people still judging you or have they become more accepting?

Waldman: There are certainly people who will judge. Some people say,

“Oh that Ayelet Waldman, being confrontational again, being outrageous again," as if that were my goal. The response from people who have dealt with issues like depression has been overwhelming and wonderful. Because even if they have no interest in doing something like this, they know that other people who suffer from depression, from anxiety, from bipolar disorder, they know what it's like to be desperately searching for a way to feel better.

You know my parents, my straight-up parents, were so wonderful and supportive and nonjudgmental. And judgment is built into the Waldman DNA even more assertively than mental illness. And they were really wonderful.

Khazan: I read that you're not saying when this took place, but to the extent that you're able to share, have the effects lasted? How long did they last?

Waldman: It's kind of interesting, the effects of the drugs have not lasted. LSD does not hang around in your system like that, but the effects of the end of the depression have lasted. I have not cycled into as low as a mood since I don't attribute that as much to LSD as to the insight brought about by that one-month experiment.

Even when my mood has dropped since then, I've had a much clearer image in my mind of what not being depressed is like, so that's one thing. It's allowed me since then to be somewhat less reactive and somewhat less impulsive. I still feel as impulsive, but for some reason since then, and with a tremendous amount of work using all these other therapeutic modalities that are boring and annoying but can be effective if you use them, I have been able to put the brakes on more inappropriate behaviors.

I still make tons of mistakes. I'll yell at my husband, but we don't have the same kind of fights really, it doesn't build to the same kind of place, or if it does I know how to repair without going to a place of suicidal ideation. I'm in this therapy now that's called dialectical behavioral therapy, and for some reason since this experience I've been more adept at the tools, and I've been more able to force myself to do them.

That being said, if it were legal, I would still be doing it, no doubt.

Instead of an “acid trip,” she took an “acid errand.”

www.theatlantic.com