Specialists investigate psychedelic therapy for those facing death*

By Luke Slattery | The Age | Jun 22 2019

Palliative care, Building A, St Vincent's Hospital Melbourne, is not a place you want to be; not, at least, for any length of time. The terminally ill, bedridden for the most part when I visit on a grey autumn afternoon, are fighting for their lives and, at the same time, contending with the unimaginable fear of imminent death. Circling discreetly around them are specialists, clinicians and nurses in light blue uniforms, with clipboards and cannulas in hand.

I'm waiting for psychologist Margaret Ross and psychiatrist Justin Dwyer, who walk swiftly along the palliative care unit's sixth-floor corridor to greet me. Ross and Dwyer are at the centre of the country's first clinical trial of psychedelic drugs for treating severe depression in the terminally ill. Within a month, they will begin recruiting 40 depressed and incurable patients in an attempt to relieve their distress with a novel treatment: between one and two 25-milligram doses of synthetic psilocybin, the psychedelic ingredient found in "magic mushrooms", accompanied by intensive psychotherapy sessions.

The trial is part of a revolutionary shift in attitudes towards psychedelic drugs believed to have therapeutic benefits for treatment-resistant depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and even commonplace addiction to alcohol or tobacco. Half a century after Woodstock, several illegal recreational substances are being recast as drugs of last resort, from psilocybin, marijuana and MDMA to ayahuasca, a psychedelic plant-based tea from the Amazon. LSD administered in high doses has lost favour among neuroscientists and therapists for largely practical reasons: its effects are too powerful, too unpredictable and too protracted.

Psilocybin, with its famed capacity to induce mystical experiences, is the focus of worldwide clinical trials. This compound, found in more than 100 species of fungi and once revered by the Aztecs who named it "flesh of the gods", is at the vanguard of attempts to tackle the despair and anguish of imminent death among the terminally ill. The depression many experience often makes it impossible to connect to family, friends, society, memory – self.

"Depression and anxiety in some cancer patients can be treated by meds, and others by talking therapy, but there are those who still face death with overwhelming fear," says Ross, who speaks rapidly, in sure-footed sentences, while her dark hair twists and falls over her shoulders.

"We can't touch it. Some try to do it tough and you eventually discover huge reservoirs of fear, hidden beneath the surface. Many withdraw from friends and family, depriving themselves and their loved ones of this precious time."

Within palliative care wards, antidepressants have not been particularly useful in treating the dying.

"Antidepressants tend to make people feel a little less awful," explains Dwyer, who has been working for 12 years at the intersection of psychology and palliative care and heads St Vincent's Department for Psychosocial Cancer Care.

"One of the psychological problems is that when you get cancer, you are defined by cancer," he says as we pass by a pod of nurses.

"What is happening to your body never leaves your mind."

"But with psilocybin, you can have an experience that enables you to reflect on the important things in life, to see life itself differently, and to have experiences where you no longer feel so tethered to suffering and to the body."

Forty-five-year-old Dwyer, who's wearing round-framed glasses and is clad entirely in Melbourne black, describes the effect on patients as a "resetting" of the brain.

We cross from the palliative care unit to the oncology and haematology wards, where some patients are receiving high-risk chemotherapy that knocks out benign as well as malignant cells, lowering their ability to fight infection – fatally in some cases.

"I see a lot of death," says Ross, as we head to the nearby lifts that will take us to their office.

"Every one of the dead leaves a mark. I have a little essence of every one of them." A psychologist since 2004, Ross turns to me with a flash of steel behind her bright gaze:

"You carry that. It's harrowing. Like ghosts," adds Dwyer.

Ross and Dwyer show me their office, a small reclaimed space personalised by the psych staff as a bulwark of normality against the reality of their daily work with the terminally ill.

"We got a run-down sty and just tried to make the best of it," says Ross.

It's from here that the psychedelic drug trial will be planned, administered and assessed. There are shelves loaded with coffee, tea, chocolate and gifted bottles of wine. Three guitar cases and a portable synthesiser stand propped in a corner, alongside a taxidermied owl picked up at a flea market, a poster illustrating several species of fungi, from the edible to the downright deadly, a bottle of Moët, a bar fridge and a book of Freud's lectures with a doodled thought bubble floating beside the ear of the father of psychoanalysis that says, hip-hop style:

"Tell me 'bout yo mama …" The doodle turns out to be Ross's work.

A 2006 study of 30 healthy volunteers at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore came to the conclusion that psilocybin, when administered "under supportive conditions", could promote mystical and euphoric experiences. Roland Griffiths, the university's wiry, silver-haired professor of psychiatry and behavioural sciences, explains that most volunteers – none had prior experience of the drug – felt a mystical sense of "unity with all people and things" on their assisted psilocybin trip, along with a sense of the "sacred" and a "deeply felt" apprehension of "ultimate reality". Most rated their trip as one of the most significant events of their life, on par with the birth of a child or the death of a parent.

A decade later, Professor Griffiths again shook the medical and psychiatric communities when he published results from a similar trial involving 51 cancer patients suffering acute despair. The study showed that 80 per cent of volunteers who received psychological counselling together with a high dose of psilocybin – 25 milligrams – had significant reductions in death-related anguish. The remaining 20 per cent reported no significant lessening of their symptoms, but no worsening. Adverse side-effects were in some cases physical – hypertension, headache and nausea – and in some psychological: fleeting anxiety and paranoia.

"But all these symptoms were temporary," Ross says.

"No rescue medication was required."

This 2016 study, and another the same year reporting similar results from New York University (NYU), was the catalyst for Ross to act. She and Dwyer, specialists in the treatment of psychological trauma among cancer patients, hope that the drug's mystical ego-dissolving effects will help release the terminally ill from depression's grip in order that they might face death with equanimity.

"I could see from these studies that after one dose of psilocybin, death anxiety declined," says 42-year-old Ross.

"Optimism rose. And the benefits were sustained for at least six months. Nothing in psychology comes close to that!" she adds, her voice vaulting an octave. It's a view echoed by Griffiths, who describes the results as

"unprecedented within the field of psychiatry".

At the hub of the brain's hardware is a "Default Mode Network" (DMN), Ross explains. It appears to be most active when people are both sedentary and reflective – as the ill tend to be – and is deeply involved with story-telling. Stories can, as writers so often attest, take on lives of their own. And this is especially true of the brain, the primal author.

"When you have depressive ruminations and anxiety, you can get into some very rigid patterns of thinking," Ross says.

"And rigid, pessimistic self-talk is a hallmark of depression."

Psilocybin stills this network, lulls it to sleep, promoting what Ross calls

"the possibility of new ways of thinking, new perspectives." When the DMN is quietened, the doors of perception are unlocked and flung open.

"It is deeply personal and allows reflection that's a little more free and profound, and that's perhaps why they've had to date such phenomenal results in the overseas trials," she says.

Experiments with a synthetic version of psilocybin began in earnest in 1960 at Harvard University under psychologist Timothy – "Turn on, tune in, drop-out" – Leary. Three years later, Leary and his assistant were sacked by Harvard, following concerns that their methods were slipshod and undergraduate volunteers were at risk. But the psychedelic genie had been released from the lab. Within a few short years, cannabis, psilocybin, LSD, violent war protests, generational disaffection and Leary himself – who had by then become a high priest of the counter-culture – were one and the same problem.

Banned in the US in 1968, psilocybin was added to a list of drugs prohibited by the 1971 UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances. Researchers had by then concluded that its risks, which include paranoia and anxiety, outweighed any potential benefits. In Australia, it's classified as a Schedule 9 substance; an illicit drug. Over time, however, researchers with an interest in the treatment of mental illness have picked up Leary's abandoned thread, and there is a powerful move afoot to make peace with the outlaw drug.

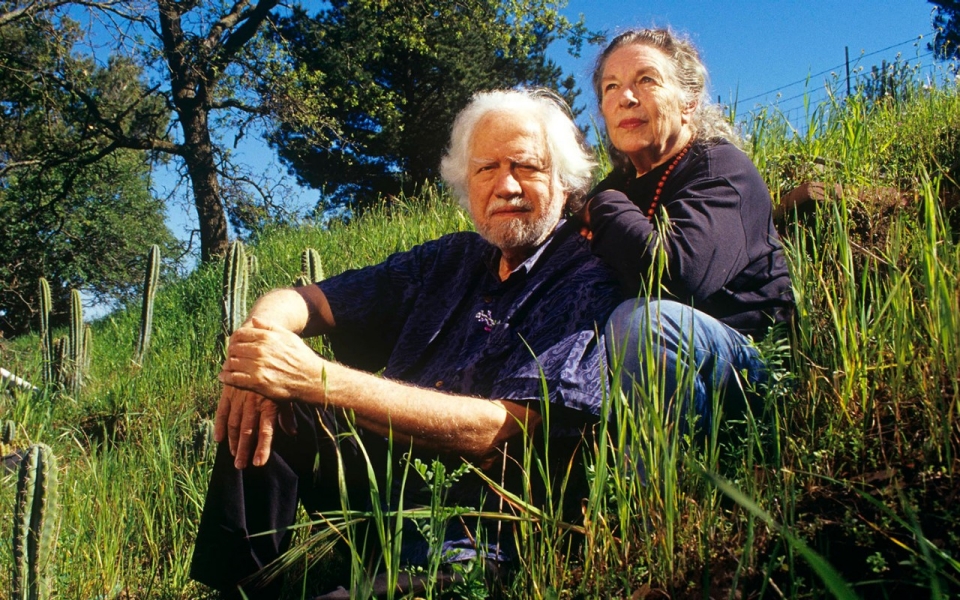

In last year's bestseller How to Change Your Mind: The New Science of Psychedelics, Michael Pollan writes of his own modest psychedelic journeys – three recent trips on different drugs are detailed in the book – as a wide-angle lens

"through which we can glimpse the subject-hood – the spirit! – of everything, animal, vegetable, even mineral … Spirits, it seems, are everywhere."

I reach Pollan in San Francisco, where the journalist and food writer is preparing for an Australian tour next month to promote the paperback edition of How to Change Your Mind. The book is part science journalism, part autobiography, part cultural history and part advocacy: it proclaims a "renaissance" of psychedelic research that might heal mental illness and unravel the mysteries of consciousness.

"There hasn't been much good news about psychedelics for the past 40 years," Pollan tells me.

"But the new cycle of scientific tests has changed that."

The book might not have been written if he hadn't spoken to the volunteers of the 2016 Johns Hopkins and NYU psilocybin trials, his curiosity piqued by word of a new wave of psychedelic research.

"Many of them had terminal diagnoses, while some had a terrifying fear of recurrence of their cancer, which had been treated," he says.

"But they all had paralysing levels of anxiety and depression, and in about two-thirds of them this was lifted by the drug experience. I ended up talking to people who had completely lost their fear of death. It was quite remarkable."

While the patients in these trials had experiences as various as their own individual dispositions, the cancer patients shared a similar inward trajectory.

"They would travel into their body imaginatively and encounter their cancer, and, in the particular case of one woman, her fear. She had had ovarian cancer and was terrified of recurrence, and during her trip, she travelled into her body and saw a black mass under her ribcage; she knew it wasn't her cancer because it wasn't in the right place, but she recognised it as her fear. So she screamed at it."

"She screamed 'Get the f... out of my body!'

And as soon as she did, the black cloud evaporated and so did her fear, and she has not been fearful since. She said that while she couldn't control her cancer – it was either going to come back or not – she could from that day control her fear. And it was exactly what she needed."

Pollan believes this kind of visual, or symbolic, encounter is something the cancer patients in the St Vincent's trial can expect. Ross describes her proposed 25-milligram dose as a

"decent measure; we don't want it to be overwhelming but neither do we want it to be underwhelming." With this relatively high dose, Pollan predicts,

"the mind is going to go where it wants to go, and you're going to have visions and memories and encounters with people and literally travel in your head to places."

The more conventionally religious among the patients may have imagined encounters with their personal deity, Pollan says, while others may have a powerful sense that a part of them will survive their death. In his own experience,

"I had a feeling of a very strong connection with nature and other people," he says,

"a powerful current of love." He suspects that the mystical experiences reported in the earlier US trials were, in part, coloured by cultural background.

"The American therapists who started all this had a more spiritual orientation," he says.

"The English are kind of allergic to spirituality. I'm looking forward to seeing what happens to the Australians."

Pollan is aware that sceptics accentuate negative drug-induced experiences such as panic attacks, hallucinations, nausea and irrational behaviour: a 12-year-old boy in Britain was found running in front of passing cars after taking magic mushrooms. But Pollan points to the difference between a precisely measured dose of psilocybin administered in a hospital, and magic mushrooms taken at a party or a rock concert. He recalls his own recent experiences:

"Was I seeing things that weren't there? Yes. Were my senses confused? Yes. I felt I could touch musical notes." But he emerged from the experience with an intense sensation of oneness with the world.

"I came out of it feeling that consciousness was much more evenly distributed over species than I had thought," he says.

Pollan is not, on the other hand, dismissive of the dangers.

"Of course, there is a dark side. People do have terrifying experiences. They can run up against existential despair and a sense of nothingness. But when people are adequately prepared, the dark experiences can even be productive. Researchers tend to use the word 'challenging', rather than 'bad', trip; and I think they really mean it. But if you're alone and you're thrown into this hellish underworld, it can induce a panic attack and leave you really rocked. You shouldn't mess around with these drugs."

Atmosphere, mood and setting are all important. As is music. For Pollan, listening to a Bach cello suite performed by Yo-Yo Ma

"had the unmistakable effect of reconciling me to death … I felt as if I'd passed beyond the reach of suffering and regret."

On the day I visit Ross and Dwyer at St Vincent's, they admit to a delay in the trial as they await a shipment from the UK of synthetic psilocybin in tablet form. Ross jokes about the fun she'll have furnishing the most chilled space in Melbourne – the only one dedicated to the legal exploration of psychedelics – with stuff from Ikea and Ishka. Two qualified therapists – Ross and Dwyer in the first instance – will assist and monitor them for the entire six-hour trip.

"We'll be as unobtrusive as possible," says Dwyer.

"It's not like we'll be saying every few minutes, 'Soooo, how are you feeling?'

The patients lead and we follow. A critical part of the treatment, he says,

"is that the experience is supported with psychological therapy before and after. This may be the most important part."

Ross nods enthusiastically.

"Think of the psychotherapy as the secret sauce," she says.

"People often think that it's just the psilocybin that creates lasting change, but it's actually the psychotherapy scaffolding the dose sessions. There are three standard preparatory sessions, the dose day and three integrative sessions post that dose session." The follow-up psychotherapy is designed to integrate the experiences in meaningful ways that

"help leverage more enduring changes in mood, thinking and behaviour. The psilocybin facilitates it; the psychotherapy weaves it into their psyche in a lasting way."

Ross worked in clinical trials prior to her doctorate, and afterwards was a research fellow in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Melbourne. A specialist in complex trauma, psycho-oncology and palliative care, she takes both the nuances and the ethics of data collection and analysis with the utmost seriousness. But the trial is not without its reputational risks, and colleagues have warned her that researching a psychedelic compound might spell career death.

"I consoled myself with the thought," she says with an impish smile,

"that a career in floristry wouldn't be so bad."

In Australia the psychedelic "renaissance", to use Michael Pollan's term, has really only begun with this year's psilocybin trial at St Vincent's. But last year, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cleared the way for a global study of MDMA (the main ingredient in ecstasy) for the treatment of trauma. Meanwhile, psilocybin-assisted therapy has been given "breakthrough" status by the FDA, accelerating, legitimising and extending research efforts. Trials involving 400 patients have begun in Europe and North America into the use of psilocybin for drug-resistant depression.

The Australian Medical Association, meanwhile, is keeping a close eye on the psychedelic trials abroad – and now at home.

"There's emerging evidence that looks promising," says the body's spokesman on psychiatry, University of Queensland professor of psychiatry Steve Kisely.

"We need more work on it."

Also sounding a cautionary note is Dr Gillinder Bedi, head of substance use research at Orygen, the National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health in Victoria. Orygen is a not-for-profit company specialising in youth mental health and Bedi, a clinical psychologist, warns that some advocates for psychedelic therapy lack experience with mental health research.

"Mental ill health is very complicated and we need to investigate a full range of responses to this kind of suffering," she says.

"I really worry about the sense coming from some quarters that the psychedelic approach is going to be a panacea to modern society's ills, and will shift the paradigm in mental illness. It strikes me as quite similar to the previous approach, that these drugs are totally bad – a few years back, we were being told that ecstasy puts holes in your brain – just from the other side. It'd be really nice to have a more middle-ground approach."

She is not an opponent, she adds, of the St Vincent's trials. On the contrary, she is calling for

"bigger studies on a broader scale", and at the same time a strong focus on the "potential risks" for the young.

Ross and Dwyer are acutely aware that their trial needs to be clinically rigorous and above reproach. Patients will be carefully selected, screened and profiled before they go anywhere near the drug, and afterwards they will be thoroughly monitored. Those with a history of psychosis, bipolar disorder, a familial history of schizophrenia, or complex trauma will be turned away.

"And we don't know enough about the impact of psilocybin on adolescents, so for safety reasons we can't include patients under 18," says Ross.

"Even under medical supervision, these drugs aren't for everyone." Some patients in the first stage of the trial will be given a placebo.

Already, 100 terminally ill people have made contact with Ross, seeking help. She shares with me an edited email from a woman who writes of her cancer metastasising and her poor prognosis, her daily struggle with "death anxiety", and her use of medication to "manage panic episodes". The unnamed patient has read about the possible benefits of psilocybin, but is "too cautious" to try it outside a hospital.

Clinical trials have found that the psilocybin experience is enhanced by eyeshades – focusing the attention inward – and music. The hospital has compiled a playlist to match the drug's lift-off stage, its peak and its taper.

"White Rabbit is a must-have," I suggest, referring to the classic Woodstock song by Jefferson Airplane. Dwyer shakes his head.

"More ambient stuff," he says.

"Everything from German electronic music to classical. Some world music, too. We've been looking for things that are unlikely to trigger memories or associations."

So "eye-wateringly good" were the results from Johns Hopkins and NYU, along with a smaller study at Imperial College, London – these revealed clear changes in brain activity among depressed people after a single dose of psilocybin – that Ross assumed that the trials would soon be replicated in Australia. She waited. But nothing happened. Meanwhile, non-profit body PRISM (Psychedelic Research in Science and Medicine), established in 2011 in the hope of contributing to the burgeoning international research in the field, made a couple of attempts to sponsor trials, one at Deakin University. They failed. Progress stalled.

In December 2017, the organisation's president, research scientist Martin Williams, spoke about the state of play in psychedelic research at a conference in Melbourne, and in the audience that day was Ross. Afterwards, she emailed Williams, a post-doctoral research fellow in medicinal chemistry at Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, to talk about the possibility of a local trial.

Williams has a clear recollection of Ross's email.

"She said, 'Look, I'm a clinician. I've seen the research, I want to research this here in Australia for my terminally ill patients. Can you help me?'" The two met the next day over coffee, and then worked on the trial protocol for eight months. When it received ethics approval from St Vincent's, Williams recalls, "nobody was more surprised than we were. But we worked hard and made it bloody difficult for them to say 'No'."

PRISM provided funding to kickstart the trial – most of the money is coming from the hospital itself – and things started to move. State and federal government approval followed. But Ross wonders if she'd have managed to push her proposal forward without the release, last year, of Pollan's book.

"I'm not sure this would have happened without Pollan," she says.

"His book started to be widely read just as the decisions were being made. I owe that guy."

It may be premature to talk, as Pollan does, about a "renaissance" in psychedelic science that might heal mental illness and redefine our understanding of consciousness itself. The test results to date have been promising, but the volunteer groups remain small. Any long-term negative impacts need to be fully gauged. Unless psychedelics prove effective in the treatment of depression in all its varieties – something that even Pollan doubts – a psilocybin pill to banish the everyday blues seems a long way away.

Ross is keen to stress that she is investigating the effects of the drug, not presupposing an effect.

"I need to underline the fact," she cautions,

"that we're doing trials. We need to be level-headed."

*From the article here :

Melbourne specialists are set to trial a new form of relief for the terminally ill struggling with severe depression: a drug linked with magic mushrooms.

www.theage.com.au