mr peabody

Bluelight Crew

Taking Psychedelics Seriously

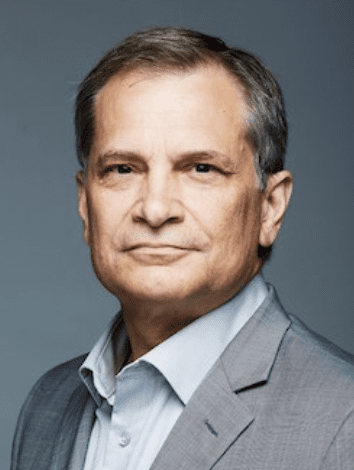

Ira Byock, MD, FAAHPM

Recently published studies in peer-reviewed journals and high-profile articles in the New Yorker, New York Times, and Wall Street Journal, have rekindled professional and public interest in the therapeutic use of psychedelic drugs. It is easy to understand the enthusiasm. The magazine and newspaper articles include accounts of patients with profound depression, demoralization associated with terminal illness, and anxiety related to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), who experienced remarkable improvements, including some who had previously considered suicide.

Nevertheless, psychiatric and palliative care clinicians who care for profoundly depressed, anxious, and seriously ill patients have every reason to be skeptical. As people become more mentally or physically ill and established treatments remain insufficiently effective, patients' susceptibility increases. Physicians play an important role in protecting vulnerable patients from spurious, nonevidence-based miracle cures, as well as from scientifically grounded, but overly zealous burdensome treatments that are certain to do more harm than good.

An abundance of caution should be accorded psychedelics, which carry real risks and are formally designated Schedule I drugs, signifying that they are dangerous, without therapeutic value, and illegal. Older clinicians remember news stories of deaths of individuals high on hallucinogens who thought they could fly, those with bad trips and flashbacks, and studies that purported to show chromosome damage associated with use of LSD.

However, given the extent of persistent emotional and existential suffering that palliative care clinicians encounter in the patients we serve, these medications deserve serious consideration by our field.

Background

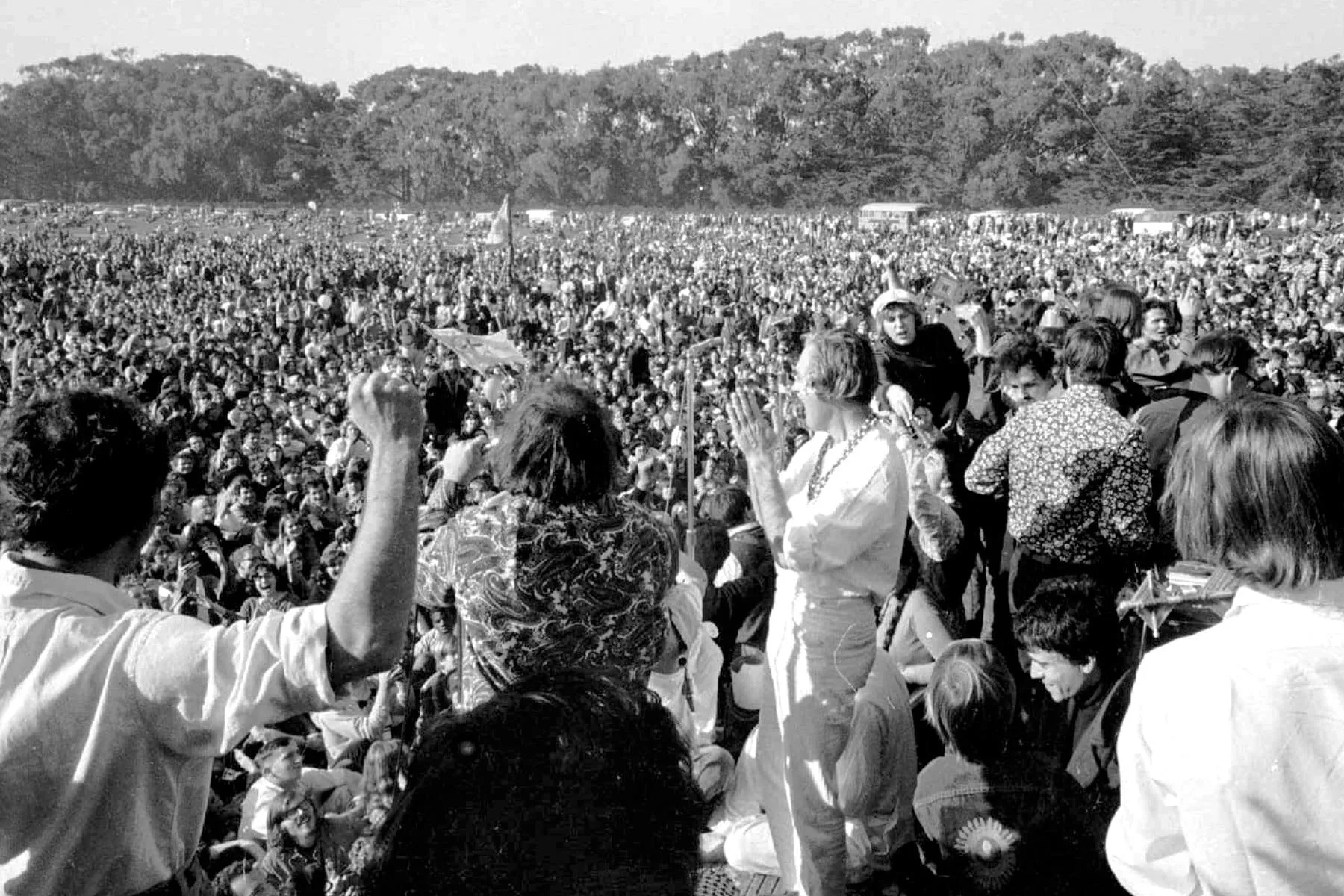

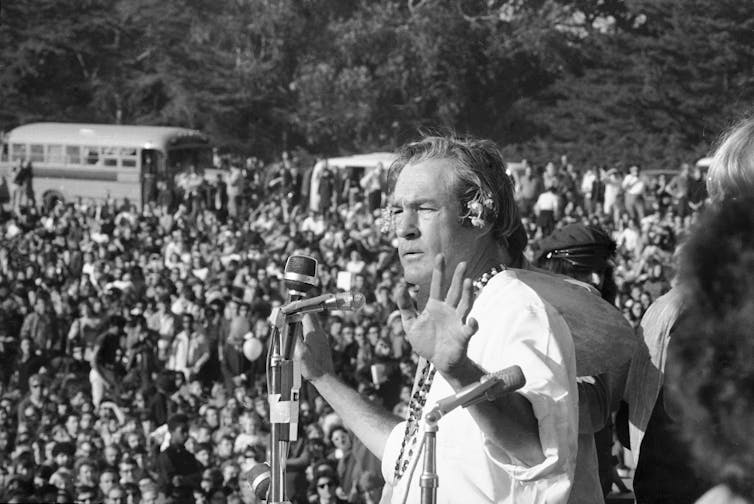

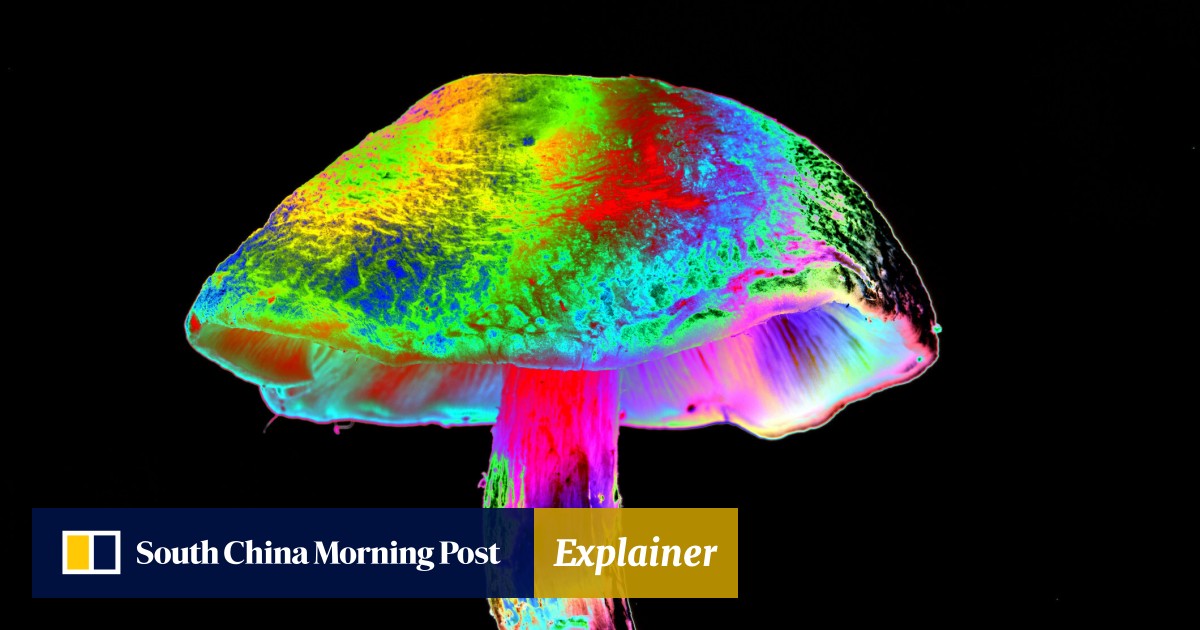

Psychedelic properties of mushrooms and cactuses have been used for centuries by indigenous cultures to induce expanded states of consciousness and spiritual experiences. During the 1950s and early 1960s, research sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health demonstrated potential for drugs of this class to markedly alleviate depression and existential suffering among people with cancer.11–13 Subsequently, non-medical use of these drugs and associated political and cultural upheavals resulted in the Schedule I classification, abruptly banning psychedelics from further clinical research and medical use. Although many of the mid-twentieth century clinical trials involved people with terminal conditions, few references to these published studies can be found in the literature of palliative medicine, a young specialty that developed after this period. Over the past 20 years, a few small clinical studies were conducted abroad, mostly in Europe and the United Kingdom. In the United States, over the past decade, with support from the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies and private funders, a few tenacious researchers earned governmental permission to carry out carefully designed trials of pharmaco-assisted therapy with psilocybin and MDMA.

The recently published research strengthens findings of earlier studies, showing significant efficacy and few adverse effects when these medications are administered as adjuncts to psychotherapy to carefully screened patients, under medical supervision. Three drugs, psilocybin, ketamine, and MDMA, have attracted most of the recent attention. Psilocybin, a naturally occurring drug found in psilocybe mushrooms, has strong and durable benefits for some patients with treatment-resistant depression, and for those with demoralization, anxiety, and depression associated with terminal illness. Ketamine, a Federal Drug Administration (FDA)-approved anesthetic with analgesic and psychedelic properties, has been used off-label in patients with treatment-resistant depression. In case studies and small clinical series, ketamine has shown notably positive effects. MDMA, a drug synthesized in 1912 as a potential anticoagulant, was later found to have strong psychoactive properties. In the 1970s and early 1980s, psychiatrists who administered MDMA in the context of psychotherapy observed sometimes dramatic improvements in patients suffering from severe, treatment-resistant PTSD.

In deciding how to think about these drugs, the distinction between skepticism and cynicism bears examining. Skepticism is warranted, but cynical nonscientific bias can result in therapeutic nihilism. The history of medicine is studded with occasional leaps in progress—consider small pox vaccination, penicillin, and computed tomography scans—that, shortly before they occurred, might have seemed too good to be true. When I graduated from medical school, the idea that duodenal ulcers were caused by bacteria would have been risible; stem cell transplants and gene-editing therapies were the stuff of science fiction. Surprising medical advances humbly remind us to suspend cynicism and that honest inquiry is warranted.

The need is great

While not only for people who are dying, specialty palliative care teams serve the sickest patients in our health systems and communities. It is, therefore, not surprising that we occasionally encounter incurably ill people whose suffering persists despite all available evidence-based treatments.

In treating pain and other physical distress, established treatment protocols guide escalations of doses and combinations of analgesics and co-analgesic medications. When a patient is dying and physical pain, dyspnea, seizures, or agitated delirium persists and causes intolerable suffering, as a last resort, comfort can reliably be achieved with proportionate sedation.

However, not all suffering is based solely in physical distress. Palliative care clinicians and teams also encounter patients whose misery is rooted in emotional, social, existential, or spiritual distress. Cancer, heart failure, liver failure, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or motor neuron disease are among the diseases that can result in a progression of personal losses: Of feeling in control. Of taking care of one's self. Of contributing to others. Of enjoyment. Of meaning and purpose. Ultimately, some ill people say they have lost any reason to go on living.

People who are incurably ill and living with progressive disease-related disabilities can experience anxiety, depression, and demoralization. Psychotherapy alone and drug treatments for such syndromes are often insufficient. Medications for depression may take weeks to become effective or prove ineffective. Antidepressants and anxiolytics carry side effects that can include mental slowing and confusion. These adverse effects are particularly common and hazardous in patients with advanced physical illness, who are also at risk of polypharmacy, multidrug interactions, and concomitant disequilibrium and falls. When nonphysical suffering persists despite prudent approaches, published, evidence-based guidelines are limited.

Severe psychological and existential suffering can rob people of feeling that life is worth living. A sense of unending helplessness and hopelessness compels some to consider ending their lives. Suicide rates have risen 24% over the past two decades and are highest among middle-aged and elderly adults, particularly men who may suffer most from feelings of dependency. Public health data from Oregon show that since implementation of the Death with Dignity Act, the large majority of patients who received prescriptions for lethal drugs were motivated by nonphysical suffering. Current or fear of future pain contributed in just 26% of cases, while loss of autonomy, decreased ability to enjoy life, and loss of dignity most often brought these people to contemplate hastening their deaths.

Exercising an abundance of caution: screening, supervision, set and setting

Prescribed to carefully screened patients, in recommended doses, in the context of professional counseling and supervision, psilocybin and MDMA have proven to be notably safe. They have no tissue toxicity, do not interfere with liver function, have scant drug–drug interactions, and carry no long-term physical effects.

These drugs are not intoxicants in the usual sense. They do not dull the senses or induce sleepiness. On the contrary, sensory perception is intensified and attention is aroused. Although abuse syndromes have been reported, few people become habituated to these drugs.

Adverse physiological effects are few and of short duration, but can be substantial. During the onset of psychedelic experiences nausea and vomiting are not unusual. In this first hour or more, visual and spatial orientation are commonly disrupted, which can give rise to anxiety. Sympathetic nervous system arousal may occur both because of fear, and from direct effects of the drugs. Particularly during the initial phase of sessions, psychedelics dissolve barriers between physical senses resulting in synesthesia; touches, smells, and tastes can take on sounds, shapes and colors. Similarly, emotions and thoughts may evoke visual images and sounds. These phenomena explain why the term hallucinogen is often used synonymously with psychedelics to refer to this class of drugs.

Clinicians and researchers familiar with this class of pharmaceuticals emphasize the importance of screening, supervision, and “set and setting.”

Screening

Not every suffering patient is a candidate for therapy involving psychedelic drugs. As a general guideline, people who have cognitive and emotional conditions associated with disorganized or diminished ego strength are not good candidates for pharmaco-assisted therapy with psychedelics. MDMA may represent a partial exception to this exclusion, because it has fewer cognitive and sensory effects and more salutary emotional and interpersonal properties. Contraindications include people with borderline personality disorders or schizophrenic tendencies.

Supervision

Supervision is necessary for ensuring safety of psychedelic experiences. Short-term psychological effects are profound. If used in unsupervised fashion by unselected and unprepared people, these drugs can be highly dangerous and, in extreme cases, cause death. The sensory effects described above interfere with hand-eye coordination and fine motor function, making operating a vehicle or machinery or even walking in public potentially dangerous. These effects are sufficient to emphasize that professionals who are skilled in managing adverse effects must be present. Most research into pharmaco-assisted therapy with psychedelics has by protocol required subjects to remain in a single comfortable room throughout the sessions. In addition to safety, the supervising therapists are able to guide patients through their experiences to optimize the drug's beneficial potential.

Set and setting

Anthropologists studying traditional use of psychedelics by shamans and indigenous people recognized the influence of expectations and motivation on subjective experience. Since the earliest psychological research into pharmaco-assisted therapy with psychedelics, clinicians have emphasized the importance of “set and setting.”

The dissolution of assumptions and diminution of barriers caused by these drugs extend to psychological and interpersonal realms of experience. An enhanced sense of connection to others not only underpins some of the therapeutic effects, but also results in vulnerability to emotional contagion. When taken without adequate preparation and when surroundings are anxiety-provoking—either physically uncomfortable or emotionally intimidating—the psychedelic experience predictably results in fear, a prolonged sense of dread, or full panic. Conversely, in controlled settings with elements of soft light, art, and appropriate music, or nature, and gentle, compassionate people, such adverse reactions are rare.

With adequate counseling and preparation, and when psychedelic experiences unfold in calm, aesthetically pleasing environments, they prove beneficial in a high proportion of cases. In these situations, the healing motivations of both therapists and patients may contribute to therapeutic outcomes.

Therapeutic effects

Clinical case studies and research trials describe common patterns of subjective experiences that are associated with therapeutic benefits for people with severe anxiety and depression. As the initial phase of psychedelic experience wanes and people regain familiar barriers between visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory senses, people typically report heightened cognitive clarity and expanded emotional receptivity. Previously unrecognized or unquestioned assumptions related to one's place in the world and relationships to nature, one's physical and social environments become available to being considered anew.

While psychedelic experiences vary significantly from one individual to another, research subjects and people interviewed for journalistic articles commonly express attributes, which include heightened clarity and confidence about their personal values and priorities, and a renewed or enhanced recognition of intrinsic meaning and value of life. People often voice a sense of exhilaration, insight, and strengthened connection to others, as well as a richer sense of relationship with nature or God. People who take psychedelics with an intention of spiritual introspection often report that the drugs opened windows into deeper realms of existential experience. In safe and supportive environments, these effects typically induce a state of wonder, conceptual frame shift, expanded capacity for love, and an intensified sense of connection. Patients living with medical conditions that had robbed them of hope or reason to live may experience a transformative shift in perspective and experience of inherent meaning, value, and worth.

Not all psychedelics drugs are alike and subcategories have been described. Drugs, such as psilocybin and LSD, classified as entheogens, are associated with introspection and new insights, shifts of perspective, and reframing of experience and relationship to others and the world. MDMA is characterized as an empathogen, referring to prominent emotional effects of interpersonal warmth, empathy, and openness. These properties may underlie the benefits of MDMA in the context of therapy for those suffering from severe PTSD.

For most of these drugs, a single six to eight-hour session or short series of sessions suffices for therapeutic benefit. Alleviation of anxiety and depression may persist for weeks to months and, for some, proves permanent. Exceptions to this treatment pattern include protocols of daily low-dose ketamine for depression and recent nonmedical reports of daily or every third day microdosing of LSD.

Political and regulatory considerations

Psychedelic drugs were closely associated with the cultural wars of the 1960s and 1970s when strong political undercurrents contributed to this class of drugs being classified Schedule I. Similarly, MDMA became well known as Ecstasy or Molly, a popular, illicit rave and party drug. In the mid-1980s, despite evidence of MDMA's striking efficacy and relative safety when used therapeutically, the FDA declared MDMA a Schedule I agent. Court rulings challenged that classification; however, in 1998 the FDA reaffirmed and made the Schedule I classification permanent.

The process of renewing clinical research of psychedelics has been long and painstaking. Future efforts to reclassify selected psychedelics, such as psilocybin, as Schedule II drugs, enabling both research and clinical administration will likely meet predictable political resistance. There are compelling reasons, however, to address the expected concerns of opponents and proceed with efforts to reclassify these drugs.

Treatment-resistant depression and anxiety associated with PTSD causes untold suffering and contributes to thousands of deaths each year. A few population health studies suggest that rising suicide rates may in part be due to suicide becoming less shameful and more socially acceptable, lowering barriers for people who feel hopeless. A person with severe depression, who has a coexisting serious, life-threatening physical condition, may feel that his or her quality of life is not worth living and may forgo arduous, but potentially life-saving treatments. Additionally, nearly one sixth of Americans live in states where physician-hastened death is legal and those with terminal illness may choose this option in absence of alternative sources of relief.

There may be higher ground on which political conservatives and progressives—as well as those on opposing sides of the issue of legalizing physician-hastened death—might build consensus. Given the life-threatening nature of persistent, treatment-resistant depression and PTSD, including among veterans of America's wars, and the rising incidence of suicide, the reclassification of psilocybin and MDMA can be legitimately cast as a right-to-try issue. Right-to-try legislation has been used to provide terminally ill patients access to potentially life-extending medications that have been tested in Phase I trials but are of uncertain benefit. Similarly, the FDA's expanded access or compassionate use provisions may make use of drugs that have not been approved available to patients who are otherwise facing death. By diminishing a desire to die among people with severe depression, anxiety, PTSD, and those with terminal cancers, genetic and neurodegenerative diseases, psychedelics may have greater life-saving effects than other drugs that have earned right-to-try and expanded access status.

Final thoughts

Faced with novel therapies with reported clinical benefits that seem too good to be true, skepticism is warranted to protect vulnerable patients from harm. Cynicism, however, may prove more dangerous still. Unscientific bias and nihilistic assumptions can keep effective treatments from people who desperately need them.

Despite the controversial history of psychedelic medications, palliative specialists who care for patients with serious medical conditions and common, difficult-to-treat nonphysical suffering have a duty to explore these hopeful, potentially life-preserving treatments. Against the backdrop of physician-hastened death becoming legal in five states, expanded research of clinical psychedelics must proceed.

In reexamining the use of psychedelics in pharmaco-assisted therapy, we must not allow preconceptions, politics, or puritanism to prevent suffering people, who are now considered helpless and hopeless, from receiving promising, at times life-saving, treatments.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5867510/