- Joined

- Jan 23, 2013

- Messages

- 30,608

Why psychedelic drugs might help cure anxiety and addiction, explained in 50+ studies

by German Lopez and Javier Zarracina on June 27, 2016

After years of struggling with treatments for his worsening cancer, Roy was miserable — anxious, depressed, hopeless. Traditional cancer treatments had left him debilitated, and it was unclear whether they would save his life.

But then Roy secured a spot in a clinical trial to test an exotic drug. The drug was not meant to cure his cancer; it was meant to cure his terror. And it worked. A few hours after taking a little pill, Roy declared to researchers, "Cancer is not important, the important stuff is love." His concerns about his imminent death had suddenly vanished — and the effects lasted for at least months, according to researchers.

It was not a traditional antidepressant, like Zoloft, or anti-anxiety medication, like Xanax, that led Roy to reevaluate his life. It was a drug that has been illegal for decades but is now at the center of a renaissance in research: psilocybin, from hallucinogenic magic mushrooms.

Psychologists and psychiatrists have been studying hallucinogens for decades — as treatment for things like alcoholism and depression, and to stimulate creativity. But support for studies dried up in the 1970s, after the federal government listed many psychedelics as Schedule 1 drugs. But now researchers are giving the drugs another look.

While stories like Roy’s are promising, we’d need hundreds, perhaps thousands, more examples — rigorously tested, preferably in large randomized, controlled experiments — to know the effects claimed in the study are real and unbiased.

But that research is worth doing. Psychedelics show promise in alleviating some of the conditions that have proven hardest to treat — addiction, obsessive compulsive disorder, end-of-life anxiety, and, in some cases, depression are notorious for their resistance to treatment. Smoking relapse rates, for instance, have been estimated at 60 to 90 percent within one year, even as smoking kills hundreds of thousands each year.

"These are among the most debilitating and costly disorders known to humankind," Matthew Johnson, one of the psychedelics researchers at Johns Hopkins University, said. "We have some things that help, but for some people they’re barely scratching the surface, [and] for some people there’s nothing that helps at all."

Psychedelics may help. But the mechanism through which they appear to help people has left doctors scratching their heads and some scientists deeply uncomfortable with their findings: These drugs appear to use chemical pathways to trigger often deeply spiritual experiences that seemingly lead to tangible, measurable, long-term changes in behavior. That is not, to say the least, how traditional medicines typically function.

There’s still, however, a lot we don't know and are just learning. So to understand what we know so far about psychedelic drugs and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy for treating some of the most stubborn psychological conditions, I read more than 50 studies analyzing their safety and efficacy and talked to researchers involved in the work.

(Note: I looked only at the studies and research on classic psychedelics, such as LSD, psilocybin from magic mushrooms, and DMT. These drugs have broadly similar effects, activating certain serotonin receptors in the brain. Although MDMA — also known as ecstasy or "Molly" — also shows promise for some conditions, like post-traumatic stress disorder, and is commonly included with psychedelics, its effects and use in therapeutic settings are too different to evaluate it alongside classic psychedelics. So I left it out of this review.)

Here’s what I learned from my look at the research.

1) The idea of using psychedelics for medicine isn't new

The idea of using psychedelic drugs as medicine is not new at all.

In 1943, Albert Hofmann serendipitously discovered the effects of LSD by, well, ingesting it in his lab in Switzerland. The discovery triggered a rush of research into LSD and similar substances in the 1950s and '60s.

Perhaps the best-known researcher of the time was Timothy Leary. Leary experimented with drugs in college, developing a particular fascination with psychedelics. His interest propelled him, after he became a young teacher at Harvard University, to begin more formally researching the drugs. This led to the creation of the Harvard Psilocybin Project, which administered psilocybin (from magic mushrooms) to graduate students and several prominent artists of the time in a set of experiments to reveal the drug’s effects on human consciousness.

Despite the odd origins, the research of the time was hopeful: Dozens and dozens of studies — not just in Leary’s lab but in many others across the country — had promising findings, suggesting psychedelics could be used in therapeutic settings to treat some of the most treatment-resistant conditions, such as addiction, anxiety, and depression.

But public concern, particularly over psychedelics slipping out of the research world and into widespread recreational use (see: Woodstock), led to a crackdown. And the research into psychedelic drugs was effectively shut down.

After a few decades, the restrictions on psychedelic drugs began to thaw. Starting in the 1990s, some researchers pushed for again treating psychedelic drugs as potential medical tools. Backed by privately funded groups like MAPS, the Beckley Foundation, and the Heffter Research Institute, researchers have overcome regulatory and funding hurdles to get some small preliminary studies done.

In part due to the hurdles to studying these drugs, the new research is preliminary and limited. The sample sizes are so small that it’s impossible to say for certain whether the findings will hold. And several of the studies don’t include control groups or placebos — gold standards in science to ensure noted effects aren’t caused by something else.

But the findings are promising and challenging. For one, to the extent that these drugs may work, they appear to do so through a very unusual mechanism: by eliciting a mystical, spiritual experience.

Here is a small sampling of how some participants in several studies since the 2000s described psychedelic experiences:

"Feelings of gratefulness, a great (powerful) remembrance of humility … of my experience of being, the experience of my being in and within the infinite."

"Not at all religious but significant in motivating me to nurture my spiritual life."

"I believe I channeled the power of the Goddess and that I hold that power in me. I believe she exists everywhere and I look for her to add spark, life, and joy to everyday ordinary situations."

"The experience expanded my conscious awareness permanently. It allows me to let go of negative ideas faster. I accept ‘what is’ easier."

"My conversation with God (golden streams of light) assuring me that everything on this plane is perfect; but I do not have the physical body/mind to fully understand."

It may be easy to dismiss these experiences. What do gods and golden streams of light have to do with medicine?

But the findings from many studies, which can involve months or years of follow-up, are promising — albeit not definitive. One very small study of 15 smokers found 12 (80 percent) managed to abstain from smoking for six months after a psilocybin treatment. A review of previous randomized controlled trials found that LSD helped alcoholics cut back on their drinking, while a much smaller study found psilocybin treatment helped people diagnosed with alcohol dependence cut back on their drinking days. Another study found that psilocybin may have helped treat depression for patients who had proven resistant to other treatments.

So how exactly are psychedelics achieving this? Researchers readily admit that they don’t have all the answers — or even total certainty that it’s solely the psychedelics at work. But drawing on the current studies and the research from the '50s and '60s, they have a theory: When people are faced with debilitating mental conditions, psychedelics — used, researchers emphasize, in controlled and supervised clinical settings — can trigger a powerful mystical experience. The experience can then provide a psychological context that makes positive behavioral change easier.

"They have profound, meaningful experiences that can sometimes help them make new insights into their own behaviors and also to reconnect with their values and priorities in terms of what’s important to them in the grander scheme of things," Albert Garcia-Romeu, another Johns Hopkins researcher, said. "When they have those kinds of experiences, it seems to be helpful for people to be able to make behavior changes down the line, like quitting smoking."

Michael Pollan wrote of some participants’ powerful experiences in an illuminating look at the research for the New Yorker:

It might sound pseudoscientific. But drug policy experts and researchers say that if the experience helps people, even if it’s not founded on the most logical grounds, it should be taken seriously.

Spiritual experiences "have been part of humanity for thousands and thousands of years," Sameet Kumar, a doctor who follows the research closely, said. "Instead of blowing them off, let’s try to understand them. What’s going on here? This is part of the human experience — a very relevant and meaningful part of the human experience. And now we have these tools to study how certain sacramental elements that are found in nature and that can be synthesized … can be used for good."

A pilot study of 12 advanced cancer patients suffering from end-of-life anxiety speaks to the potential. The patients all had diagnosed anxiety and stress disorders, driven in large part by their looming deaths. After psilocybin treatment, participants generally showed improvements on metrics used to evaluate mood, depression, and anxiety — although the findings were not always statistically significant.

While the study couldn’t verify due to its small sample size whether psilocybin alone led to the gains, participants reported that the spiritual experience helped them reevaluate "how their illness had impacted their lives, relationships with family and close friends, and sense of ontological [metaphysical] security."

Charles Grob, a psychedelics researcher at UCLA who co-authored the study, pointed to Canadian research done in the 1950s with alcoholics as proof that the mystical experience triggered by psychedelics is key: Among patients in the Canadian research, the best predictor of who had the best outcomes (sobriety) "was that during the course of their many-hour one-psychedelic session, they had a powerful mystical-level experience."

Johnson of Johns Hopkins concurred, citing his studies: "For either [cancer-related end-of-life anxiety] or smoking cessation treatment, we found that the degree of mystical experience … is predictive of long-term beneficial effects — of reductions in anxiety and depression [and] reductions in cigarette smoking."

One way of understanding the effect is by looking at it as the opposite of a traumatic experience, as the smoking study explained it:

"What it represents in the brain, we’re not really sure," James Rucker, a clinical lecturer at King's College London who worked on the depression study, said. "The way they describe it is often symbolic of what’s going on in their head. Take the goddess leading you through. Maybe it’s the goddess leading you through your depression and out the other side — if you take the metaphor like that."

3) We don’t really know why psychedelics trigger such powerful mystical experiences

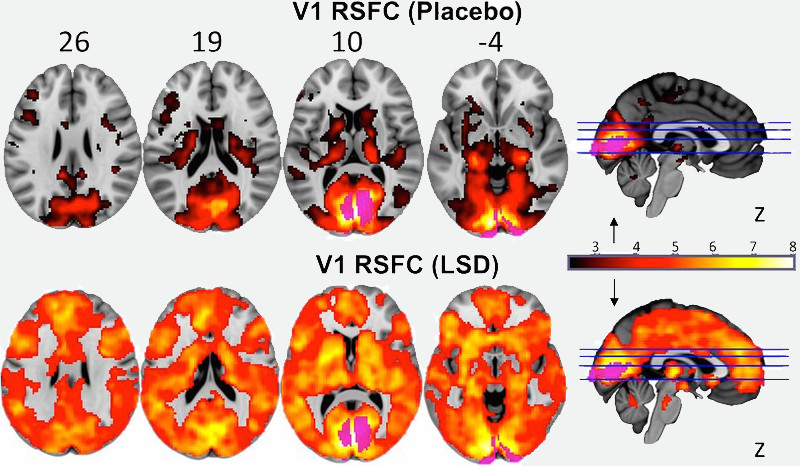

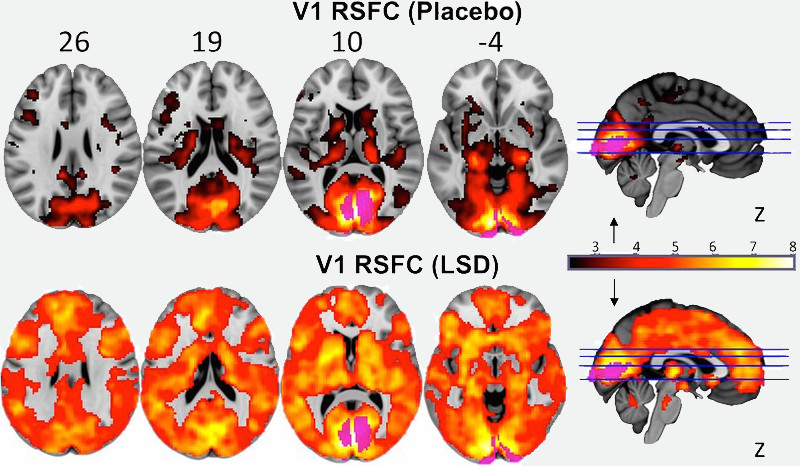

In a recent study, British researchers used brain imaging techniques to gauge how the brain looks on LSD versus a placebo. They found big differences between LSD and the placebo, with the images of the brain on LSD showing much more connectivity between different sections of the mind.

This can help explain visual hallucinations, because it means various parts of the brain — not just the visual cortex at the back of the mind — are communicating during an LSD trip.

This, researchers argued, may show not just why psychedelic drugs trigger hallucinogenic experiences but also why they may be able to help people. "In many psychiatric disorders, the brain may be viewed as having become entrenched in pathology, such that core behaviors become automated and rigid," the researchers wrote. "Consistent with their ‘entropic’ effect on cortical activity, psychedelics may work to break down such disorders by dismantling the patterns of activity on which they rest."

"The idea with the psychedelics is to essentially try to shake the brain up a bit," Rucker, who didn’t take part in the brain imaging study, explained. "To try and lend the person who’s suffering a new perspective and try to change their behavior."

This is one of the few studies so far that analyzed how the mechanical, physical effects of psychedelics on the brain may help patients. Other research is unclear on the exact mechanisms, but it suggests that the classic psychedelics affect serotonin and, in the case of LSD, dopamine receptors in a way that may help elevate people’s moods.

According to Garcia-Romeu of Johns Hopkins, it’s likely these physical factors work with the spiritual experience to help people. "They all co-occur," he said. "It’s not like right now as I’m talking to you, there’s not activity in the temporal lobe in your brain, which is both chemical and electrical. All of this stuff is happening at the same time. But what we experience obviously is primary. You’re hearing my voice, so your subjective experience is focused in on what is happening in your field of consciousness, as opposed to the electrical … and neurochemical signals in your brain."

4) One reason psychedelics may work: They treat the person’s context, not just their illness

"My personal opinion is that the reason these kinds of conditions are so hard to treat from a standard medical perspective is that there’s something more to them than just the illness," Garcia-Romeu said, pointing to addiction as an example.

"Oftentimes we have to do actual therapy," he added. "We can’t just give them a pill to make their problems go away. We have to really delve into things like childhood trauma and current life situations and relationships and whether those relationships are healthy or toxic and how people feel about themselves."

Kumar works closely with cancer patients as a psychologist in a South Florida cancer center. He thinks psychedelic-assisted treatments could be a great boon to his line of work with late-term cancer patients, who struggle with crippling end-of-life anxiety that’s frequently impossible to treat.

"Patients with advanced cancer oftentimes don’t have the healthy coping tools that often take a lifetime of practice to get — healthy stress management, a set of spiritual beliefs that can be comforting, or an understanding or sense of purpose and meaning in their lives," Kumar said. As a late-term cancer patient, "you are suddenly faced with a situation in which you don’t have a lot of time, your physical health is in jeopardy, your cognition is dicey, and there just isn’t a whole lot of time to get a lot of stuff in place. Psychedelics are a very rapid way to induce very meaningful change in people."

continued with a grip of links as well http://www.vox.com/2016/6/27/11544250/psychedelic-drugs-lsd-psilocybin-effects

..........................................................

I cured all my addiction issues by changing my cognition. I use psilocybin a handful of times a year both as a booster against slipping back into destructive thinking and as a brief escape from sober normality. I believe that psychedelics can help promote positive cognitive changes necessary for the human race to heal and survive.

by German Lopez and Javier Zarracina on June 27, 2016

After years of struggling with treatments for his worsening cancer, Roy was miserable — anxious, depressed, hopeless. Traditional cancer treatments had left him debilitated, and it was unclear whether they would save his life.

But then Roy secured a spot in a clinical trial to test an exotic drug. The drug was not meant to cure his cancer; it was meant to cure his terror. And it worked. A few hours after taking a little pill, Roy declared to researchers, "Cancer is not important, the important stuff is love." His concerns about his imminent death had suddenly vanished — and the effects lasted for at least months, according to researchers.

It was not a traditional antidepressant, like Zoloft, or anti-anxiety medication, like Xanax, that led Roy to reevaluate his life. It was a drug that has been illegal for decades but is now at the center of a renaissance in research: psilocybin, from hallucinogenic magic mushrooms.

Psychologists and psychiatrists have been studying hallucinogens for decades — as treatment for things like alcoholism and depression, and to stimulate creativity. But support for studies dried up in the 1970s, after the federal government listed many psychedelics as Schedule 1 drugs. But now researchers are giving the drugs another look.

While stories like Roy’s are promising, we’d need hundreds, perhaps thousands, more examples — rigorously tested, preferably in large randomized, controlled experiments — to know the effects claimed in the study are real and unbiased.

But that research is worth doing. Psychedelics show promise in alleviating some of the conditions that have proven hardest to treat — addiction, obsessive compulsive disorder, end-of-life anxiety, and, in some cases, depression are notorious for their resistance to treatment. Smoking relapse rates, for instance, have been estimated at 60 to 90 percent within one year, even as smoking kills hundreds of thousands each year.

"These are among the most debilitating and costly disorders known to humankind," Matthew Johnson, one of the psychedelics researchers at Johns Hopkins University, said. "We have some things that help, but for some people they’re barely scratching the surface, [and] for some people there’s nothing that helps at all."

Psychedelics may help. But the mechanism through which they appear to help people has left doctors scratching their heads and some scientists deeply uncomfortable with their findings: These drugs appear to use chemical pathways to trigger often deeply spiritual experiences that seemingly lead to tangible, measurable, long-term changes in behavior. That is not, to say the least, how traditional medicines typically function.

There’s still, however, a lot we don't know and are just learning. So to understand what we know so far about psychedelic drugs and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy for treating some of the most stubborn psychological conditions, I read more than 50 studies analyzing their safety and efficacy and talked to researchers involved in the work.

(Note: I looked only at the studies and research on classic psychedelics, such as LSD, psilocybin from magic mushrooms, and DMT. These drugs have broadly similar effects, activating certain serotonin receptors in the brain. Although MDMA — also known as ecstasy or "Molly" — also shows promise for some conditions, like post-traumatic stress disorder, and is commonly included with psychedelics, its effects and use in therapeutic settings are too different to evaluate it alongside classic psychedelics. So I left it out of this review.)

Here’s what I learned from my look at the research.

1) The idea of using psychedelics for medicine isn't new

The idea of using psychedelic drugs as medicine is not new at all.

In 1943, Albert Hofmann serendipitously discovered the effects of LSD by, well, ingesting it in his lab in Switzerland. The discovery triggered a rush of research into LSD and similar substances in the 1950s and '60s.

Perhaps the best-known researcher of the time was Timothy Leary. Leary experimented with drugs in college, developing a particular fascination with psychedelics. His interest propelled him, after he became a young teacher at Harvard University, to begin more formally researching the drugs. This led to the creation of the Harvard Psilocybin Project, which administered psilocybin (from magic mushrooms) to graduate students and several prominent artists of the time in a set of experiments to reveal the drug’s effects on human consciousness.

Despite the odd origins, the research of the time was hopeful: Dozens and dozens of studies — not just in Leary’s lab but in many others across the country — had promising findings, suggesting psychedelics could be used in therapeutic settings to treat some of the most treatment-resistant conditions, such as addiction, anxiety, and depression.

But public concern, particularly over psychedelics slipping out of the research world and into widespread recreational use (see: Woodstock), led to a crackdown. And the research into psychedelic drugs was effectively shut down.

After a few decades, the restrictions on psychedelic drugs began to thaw. Starting in the 1990s, some researchers pushed for again treating psychedelic drugs as potential medical tools. Backed by privately funded groups like MAPS, the Beckley Foundation, and the Heffter Research Institute, researchers have overcome regulatory and funding hurdles to get some small preliminary studies done.

In part due to the hurdles to studying these drugs, the new research is preliminary and limited. The sample sizes are so small that it’s impossible to say for certain whether the findings will hold. And several of the studies don’t include control groups or placebos — gold standards in science to ensure noted effects aren’t caused by something else.

But the findings are promising and challenging. For one, to the extent that these drugs may work, they appear to do so through a very unusual mechanism: by eliciting a mystical, spiritual experience.

Here is a small sampling of how some participants in several studies since the 2000s described psychedelic experiences:

"Feelings of gratefulness, a great (powerful) remembrance of humility … of my experience of being, the experience of my being in and within the infinite."

"Not at all religious but significant in motivating me to nurture my spiritual life."

"I believe I channeled the power of the Goddess and that I hold that power in me. I believe she exists everywhere and I look for her to add spark, life, and joy to everyday ordinary situations."

"The experience expanded my conscious awareness permanently. It allows me to let go of negative ideas faster. I accept ‘what is’ easier."

"My conversation with God (golden streams of light) assuring me that everything on this plane is perfect; but I do not have the physical body/mind to fully understand."

It may be easy to dismiss these experiences. What do gods and golden streams of light have to do with medicine?

But the findings from many studies, which can involve months or years of follow-up, are promising — albeit not definitive. One very small study of 15 smokers found 12 (80 percent) managed to abstain from smoking for six months after a psilocybin treatment. A review of previous randomized controlled trials found that LSD helped alcoholics cut back on their drinking, while a much smaller study found psilocybin treatment helped people diagnosed with alcohol dependence cut back on their drinking days. Another study found that psilocybin may have helped treat depression for patients who had proven resistant to other treatments.

So how exactly are psychedelics achieving this? Researchers readily admit that they don’t have all the answers — or even total certainty that it’s solely the psychedelics at work. But drawing on the current studies and the research from the '50s and '60s, they have a theory: When people are faced with debilitating mental conditions, psychedelics — used, researchers emphasize, in controlled and supervised clinical settings — can trigger a powerful mystical experience. The experience can then provide a psychological context that makes positive behavioral change easier.

"They have profound, meaningful experiences that can sometimes help them make new insights into their own behaviors and also to reconnect with their values and priorities in terms of what’s important to them in the grander scheme of things," Albert Garcia-Romeu, another Johns Hopkins researcher, said. "When they have those kinds of experiences, it seems to be helpful for people to be able to make behavior changes down the line, like quitting smoking."

Michael Pollan wrote of some participants’ powerful experiences in an illuminating look at the research for the New Yorker:

Death looms large in the journeys taken by the cancer patients. A woman I'll call Deborah Ames, a breast-cancer survivor in her sixties (she asked not to be identified), described zipping through space as if in a video game until she arrived at the wall of a crematorium and realized, with a fright, "I’ve died and now I’m going to be cremated. The next thing I know, I’m below the ground in this gorgeous forest, deep woods, loamy and brown. There are roots all around me and I’m seeing the trees growing, and I’m part of them. It didn’t feel sad or happy, just natural, contented, peaceful. I wasn’t gone. I was part of the earth." Several patients described edging up to the precipice of death and looking over to the other side. Tammy Burgess, given a diagnosis of ovarian cancer at fifty-five, found herself gazing across "the great plain of consciousness. It was very serene and beautiful. I felt alone but I could reach out and touch anyone I’d ever known. When my time came, that’s where my life would go once it left me and that was O.K."

It might sound pseudoscientific. But drug policy experts and researchers say that if the experience helps people, even if it’s not founded on the most logical grounds, it should be taken seriously.

Spiritual experiences "have been part of humanity for thousands and thousands of years," Sameet Kumar, a doctor who follows the research closely, said. "Instead of blowing them off, let’s try to understand them. What’s going on here? This is part of the human experience — a very relevant and meaningful part of the human experience. And now we have these tools to study how certain sacramental elements that are found in nature and that can be synthesized … can be used for good."

A pilot study of 12 advanced cancer patients suffering from end-of-life anxiety speaks to the potential. The patients all had diagnosed anxiety and stress disorders, driven in large part by their looming deaths. After psilocybin treatment, participants generally showed improvements on metrics used to evaluate mood, depression, and anxiety — although the findings were not always statistically significant.

While the study couldn’t verify due to its small sample size whether psilocybin alone led to the gains, participants reported that the spiritual experience helped them reevaluate "how their illness had impacted their lives, relationships with family and close friends, and sense of ontological [metaphysical] security."

Charles Grob, a psychedelics researcher at UCLA who co-authored the study, pointed to Canadian research done in the 1950s with alcoholics as proof that the mystical experience triggered by psychedelics is key: Among patients in the Canadian research, the best predictor of who had the best outcomes (sobriety) "was that during the course of their many-hour one-psychedelic session, they had a powerful mystical-level experience."

Johnson of Johns Hopkins concurred, citing his studies: "For either [cancer-related end-of-life anxiety] or smoking cessation treatment, we found that the degree of mystical experience … is predictive of long-term beneficial effects — of reductions in anxiety and depression [and] reductions in cigarette smoking."

One way of understanding the effect is by looking at it as the opposite of a traumatic experience, as the smoking study explained it:

It is our contention that in a similar fashion, the psychedelic-occasioned peak experience may function as a salient, discrete event producing inverse PTSD-like effects-that is, persisting changes in behavior (and presumably the brain) associated with lasting benefit. By "PTSD-like" we are not presuming that these experiences necessarily share common biological mechanisms with PTSD. Rather, we are proposing that these experiences are "PTSD-like" in the sense that a single discrete event can cause lasting behavioral (and likely biological) changes, and "inverse" in the sense that these lasting changes are beneficial in nature, as opposed to deleterious.

"What it represents in the brain, we’re not really sure," James Rucker, a clinical lecturer at King's College London who worked on the depression study, said. "The way they describe it is often symbolic of what’s going on in their head. Take the goddess leading you through. Maybe it’s the goddess leading you through your depression and out the other side — if you take the metaphor like that."

3) We don’t really know why psychedelics trigger such powerful mystical experiences

In a recent study, British researchers used brain imaging techniques to gauge how the brain looks on LSD versus a placebo. They found big differences between LSD and the placebo, with the images of the brain on LSD showing much more connectivity between different sections of the mind.

This can help explain visual hallucinations, because it means various parts of the brain — not just the visual cortex at the back of the mind — are communicating during an LSD trip.

This, researchers argued, may show not just why psychedelic drugs trigger hallucinogenic experiences but also why they may be able to help people. "In many psychiatric disorders, the brain may be viewed as having become entrenched in pathology, such that core behaviors become automated and rigid," the researchers wrote. "Consistent with their ‘entropic’ effect on cortical activity, psychedelics may work to break down such disorders by dismantling the patterns of activity on which they rest."

"The idea with the psychedelics is to essentially try to shake the brain up a bit," Rucker, who didn’t take part in the brain imaging study, explained. "To try and lend the person who’s suffering a new perspective and try to change their behavior."

This is one of the few studies so far that analyzed how the mechanical, physical effects of psychedelics on the brain may help patients. Other research is unclear on the exact mechanisms, but it suggests that the classic psychedelics affect serotonin and, in the case of LSD, dopamine receptors in a way that may help elevate people’s moods.

According to Garcia-Romeu of Johns Hopkins, it’s likely these physical factors work with the spiritual experience to help people. "They all co-occur," he said. "It’s not like right now as I’m talking to you, there’s not activity in the temporal lobe in your brain, which is both chemical and electrical. All of this stuff is happening at the same time. But what we experience obviously is primary. You’re hearing my voice, so your subjective experience is focused in on what is happening in your field of consciousness, as opposed to the electrical … and neurochemical signals in your brain."

4) One reason psychedelics may work: They treat the person’s context, not just their illness

"My personal opinion is that the reason these kinds of conditions are so hard to treat from a standard medical perspective is that there’s something more to them than just the illness," Garcia-Romeu said, pointing to addiction as an example.

"Oftentimes we have to do actual therapy," he added. "We can’t just give them a pill to make their problems go away. We have to really delve into things like childhood trauma and current life situations and relationships and whether those relationships are healthy or toxic and how people feel about themselves."

Kumar works closely with cancer patients as a psychologist in a South Florida cancer center. He thinks psychedelic-assisted treatments could be a great boon to his line of work with late-term cancer patients, who struggle with crippling end-of-life anxiety that’s frequently impossible to treat.

"Patients with advanced cancer oftentimes don’t have the healthy coping tools that often take a lifetime of practice to get — healthy stress management, a set of spiritual beliefs that can be comforting, or an understanding or sense of purpose and meaning in their lives," Kumar said. As a late-term cancer patient, "you are suddenly faced with a situation in which you don’t have a lot of time, your physical health is in jeopardy, your cognition is dicey, and there just isn’t a whole lot of time to get a lot of stuff in place. Psychedelics are a very rapid way to induce very meaningful change in people."

continued with a grip of links as well http://www.vox.com/2016/6/27/11544250/psychedelic-drugs-lsd-psilocybin-effects

..........................................................

I cured all my addiction issues by changing my cognition. I use psilocybin a handful of times a year both as a booster against slipping back into destructive thinking and as a brief escape from sober normality. I believe that psychedelics can help promote positive cognitive changes necessary for the human race to heal and survive.