NicoOregon

Bluelighter

- Joined

- Jan 15, 2018

- Messages

- 179

Interesting study. I knew there was a way! Looking forward to reading thoughts:

Use of microdoses for induction of

buprenorphine treatment with overlapping opioid use.

Division of Addiction, University

Psychiatric Services

Because induction of buprenorphine is a difficult experience, due to withdrawal

symptoms. Furthermore, tapering of the full agonist bears the risk of relapse to illicit opioid use.

Cases: We present two cases of successful initiation of buprenorphine treatment with the

Bernese method, ie, gradual induction overlapping with full agonist use. The first patient began

buprenorphine with overlapping street heroin use after repeatedly experiencing relapse, with-

drawal, and trauma reactivation symptoms during conventional induction. The second patient

was maintained on high doses of diacetylmorphine (ie, pharmaceutical heroin) and methadone

during induction. Both patients tolerated the induction procedure well and reported only mild

withdrawal symptoms.

Discussion: Overlapping induction of buprenorphine maintenance treatment with full µ-opioid

receptor agonist use is feasible and may be associated with better tolerability and acceptability

in some patients compared to the conventional method of induction.

Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation

Dove Press

Use of microdoses for induction of buprenorphine treatment with overlapping full opioid agonist use: the Bernese method

Robert Hämmig, Antje Kemter, [...], and Marc Vogel

Additional article information

Abstract

Background

Buprenorphine is a partial µ-opioid receptor agonist used for maintenance treatment of opioid dependence. Because of the partial agonism and high receptor affinity, it may precipitate withdrawal symptoms during induction in persons on full µ-opioid receptor agonists. Therefore, current guidelines and drug labels recommend leaving a sufficient time period since the last full agonist use, waiting for clear and objective withdrawal symptoms, and reducing pre-existing full agonist therapies before administering buprenorphine. However, even with these precautions, for many patients the induction of buprenorphine is a difficult experience, due to withdrawal symptoms. Furthermore, tapering of the full agonist bears the risk of relapse to illicit opioid use.

Cases

We present two cases of successful initiation of buprenorphine treatment with the Bernese method, ie, gradual induction overlapping with full agonist use. The first patient began buprenorphine with overlapping street heroin use after repeatedly experiencing relapse, withdrawal, and trauma reactivation symptoms during conventional induction. The second patient was maintained on high doses of diacetylmorphine (ie, pharmaceutical heroin) and methadone during induction. Both patients tolerated the induction procedure well and reported only mild withdrawal symptoms.

Discussion

Overlapping induction of buprenorphine maintenance treatment with full µ-opioid receptor agonist use is feasible and may be associated with better tolerability and acceptability in some patients compared to the conventional method of induction.

Keywords: subutex, suboxone, heroin, opiate, substitution

Introduction

Buprenorphine is a partial µ-opioid agonist and κ-opioid antagonist used for maintenance treatment of opioid dependence (OMT). It is as effective as methadone in suppressing opioid use and is slightly less effective in retaining patients in treatment.1 Buprenorphine has potential advantages over methadone, including a lower risk of overdose due to the partial agonism and the associated “low ceiling effect” for respiratory depression, fewer pharmaceutical interactions, and absence of corrected QT interval (QTc)-prolongation.2–4However, because buprenorphine replaces other opioids at the µ-receptor due to its high affinity, the partial agonism at the µ-opioid receptor may precipitate severe withdrawal in persons regularly using opioids.5Therefore, guidelines on buprenorphine induction in OMT and drug labels recommend consideration of the nature of opioid dependence (ie, long- or short-acting opioid), its degree, and the time since last opioid use:4,6,7 physicians should leave sufficient time between last use of opioid agonist and buprenorphine. This time depends on the opioid used and ranges between 4 (heroin) and 36–48 hours (methadone). Moreover, waiting for observable opioid withdrawal symptoms before starting buprenorphine is recommended. A switch of the substitute from methadone to buprenorphine requires prior tapering of methadone to a daily dose of 30–40 mg.8

Clinical experience shows that despite these precautions, the induction of buprenorphine can precipitate severe opioid withdrawal. In addition to the discomfort, this may lead to treatment dropout or relapse with full opioid agonists. Precipitated withdrawal and the complicated induction process may result in differences between buprenorphine and methadone with regard to treatment retention in the first 2 weeks.9

Between 40% and 60% of buprenorphine-maintained persons concomitantly use full µ-receptor agonists.10–12 According to patients’ accounts and experimental studies, this use is not associated with opioid withdrawal but attenuated subjective opioid effects such as euphoria.13 The attenuation persists for some days after termination of buprenorphine use. The likely explanation is the higher opioid receptor binding capacity of buprenorphine. Other opioid agonists and their active metabolites can replace only a small fraction of buprenorphine at the receptor. Moreover, because of its low dissociation constant, buprenorphine separates slowly from the receptor once it is bound.14 The slow association/dissociation kinetics allow for 72-hour dosing intervals in buprenorphine treatment.4,15 Because of the high µ-opioid receptor affinity, buprenorphine can replace a full µ-agonist at the receptor while at the same time providing less µ-opioid effects.16

Resnick et al17 showed that repetitive administration of the µ-antagonist naloxone quickly leads to a maximum of withdrawal symptoms that decline afterward despite continued naloxone application. This phenomenon was used in the 1980s in the development of rapid withdrawal procedures.18 Furthermore, it was shown that a very small dose of 0.2 mg buprenorphine intravenous (iv) did not produce opioid withdrawal in methadone-maintained individuals.19

From this, we developed the following hypotheses: 1) Repetitive administration of very small buprenorphine doses with sufficient dosing intervals (eg, 12 hours) should not precipitate opioid withdrawal. 2) Because of the long receptor binding time, buprenorphine will accumulate at the receptor. 3) Over time, an increasing amount of a full µ-agonist will be replaced by buprenorphine at the opioid receptor.

Hence, overlapping induction of buprenorphine with ongoing use of street heroin or maintenance on high doses of a full µ-agonist should be possible without precipitating severe opioid withdrawal. We present two cases in which we tested this procedure, termed the Bernese method. In both patients, we used sublingual buprenorphine, as the buprenorphine/naloxone combination is not available in Switzerland. We first introduced this method in 2010, and described the initial treatment of the first case in German.20 The second case has never been published before. We have successfully applied the Bernese method in a number of patients since. Clinical treatment was conducted in agreement with the patients, and both patients consented to the publication of their data in anonymized form.

Case 1

The patient grew up in an unremarkable middle-class family. At the age of 12, she was sexually abused and developed post-traumatic stress disorder. At the age of 15, she began using various substances (psilocybin, 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine, cocaine, cannabis, and, sporadically, heroin). At the age of 18, she experienced a major depressive episode with a suicide attempt. She then started suffering from bulimia, which remitted at age 23.

Preceding a job-related stay in Central America, she used heroin for several weeks. During the stay, she was unable to obtain heroin and began using crack-cocaine, quickly developing a severe dependence. Back in Switzerland, she successfully managed to stop crack-cocaine, but reinitiated heroin use. After several months, she opted for buprenorphine treatment but experienced the induction-associated symptoms as very stressful.

She stabilized during treatment, tapered buprenorphine and abstained from opioids for several months before initiating sporadic use of heroin again. At the age of 30, when she entered our outpatient treatment, she sniffed 3 g of street heroin daily.

Conventional induction

The patient was ordered to return in the morning. She had then abstained from heroin for more than 8 hours and showed distinct symptoms of withdrawal (rhinorrhea, mydriasis, and stomach cramps).

Buprenorphine was started at 0.4 mg sublingually, and the same dose was administered four times with an interval of 30 minutes. Starting with the first and increasing with each further administration, she felt worse and suffered from diarrhea. She experienced trauma-related flashbacks and showed severe anxiety and dissociative thinking. Her state did not improve with two further doses of 8 mg buprenorphine. We then administered 50 mg of promazine po, which brought some relief, and after 8 hours of surveillance she had improved sufficiently to return home.

Bernese method

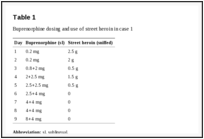

After 2 weeks, the patient stopped taking buprenorphine and reinitiated sniffed heroin use. A week later, she presented herself again with the wish for buprenorphine treatment, but was afraid of being unable to tolerate the induction process and the related symptoms. We suggested overlapping buprenorphine induction with the Bernese method (ie, start with a low dose of 0.2 mg buprenorphine overlapping with heroin use, small daily dose increases, and abrupt cessation of heroin use at sufficient dose). Furthermore, we offered her the support of a physician (via text message) to flexibly adapt dosing. Buprenorphine dosing and use of street heroin were noted (Table 1). The patient tolerated this induction process much better than the conventional induction.

Table 1

Buprenorphine dosing and use of street heroin in case 1

She was stable with 12 mg/d buprenorphine. Throughout further treatment she stopped buprenorphine several times, used heroin, and afterward reinitiated buprenorphine treatment with the Bernese method. However, after these short disruptions, she increased buprenorphine dosing more rapidly. She then developed a major depressive episode and was started on 20 mg/d escitalopram and psychotherapy. With this treatment, she stabilized further and abstained from heroin for 2.5 years.

Because of the desire for complete abstinence, she then wanted to stop buprenorphine and initiate naltrexone treatment to reduce opioid craving. However, she was worried about the first week after cessation of buprenorphine, where naltrexone should not be administered according to the drug label.

Overlapping induction of a full antagonist

We assumed that naltrexone could be initiated analogous to the overlapping induction of buprenorphine. Preliminary data suggest that very low naltrexone doses during µ-agonist treatment may not be associated with reduced analgesic efficacy.21However, naltrexone tablets available in Switzerland contain a rather large dose of 50 mg drug. After tapering of buprenorphine to 2 mg/d, the patient started with small amounts of naltrexone scratched off from a tablet and increased the dose daily. She did not develop any withdrawal symptoms or craving, stopped buprenorphine, and increased naltrexone to 25 mg/d. After several months, she stopped naltrexone and has since been abstinent for an ongoing period of 3 years and 3 months.

Case 2

After using heroin for several years and unsuccessful treatment attempts with methadone, the patient entered heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) at the age of 49. In addition to heroin dependence, he fulfilled International Classification of Diseases-10 criteria for cocaine and tobacco dependence. He suffered from mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic hepatitis C-infection, and recurrent thrombosis due to groin injection. Furthermore, the patient had a long history of substance-related crime and imprisonment. Throughout 6 years in HAT, he completely stopped using street heroin, reduced cocaine use to once per month, and entered a job rehabilitation program. At this point, he received 200 mg diacetylmorphine (DAM; ie, pharmaceutical heroin) iv twice daily, and 40 mg of methadone to avoid nighttime withdrawal symptoms. Because he wanted to stop iv injections, iv DAM was switched to oral tablets at the equivalent dose of 400 mg twice daily. After another 2 months without using nonprescribed opioids, the patient desired a less rigid therapeutic setting (HAT entails twice daily medication dispensing 365 days per year). We suggested switching to buprenorphine. Because of fears that the guideline-recommended reduction of the full agonist dose prior to switching might lead to a destabilization, we suggested induction with the Bernese method.

Overlapping induction of buprenorphine with maintenance on full µ-agonists

At first administration of buprenorphine, the patient had been on a stable oral maintenance dose of 40 mg methadone and 800 mg DAM per day for 2 months. It is important to note that we did not grant take-home dosages for DAM tablets, but substituted these with methadone. The patient received methadone instead of DAM when he could not attend on-site dispensing. He completed the short opioid withdrawal scale (SOWS) daily. The SOWS is a ten-item questionnaire rating withdrawal symptoms on a scale of 0–3, yielding a maximum score of 30.22 Another question on opiate craving answered likewise was added. Furthermore, every third day the patient completed visual analog scales related to general mental state and feeling stressed, relaxed, and nervous.

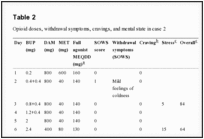

We began with a dose of 0.2 mg buprenorphine sublingually, which was well tolerated. The next day, the dose was increased to 0.4 mg twice daily. We decided to dose twice daily in the beginning as the effect of buprenorphine is shorter at lower doses and switched to once-daily dosing at 2 mg/d. Buprenorphine was principally increased by 0.4 mg/d up to a dose of 3.4 mg, then we increased the daily dose by 20%–30%. The patient tolerated buprenorphine induction very well but reported mild opioid withdrawal symptoms on day 8 at 3 mg/d and day 11 at 4.8 mg/d (Table 2). At 6 mg/d on day 14, the patient went on a 5-day vacation and was switched to 180 mg/d methadone (as DAM tablets were not available as take-home medication), while the buprenorphine dose remained unchanged. During days 13–16, he reported slightly stronger withdrawal symptoms, although they were still mild to moderate (maximum score of 7 in the SOWS). Days 15 and 16 were the only days during induction on which he reported any opiate craving (moderate). Unfortunately, he did not complete the SOWS on days 17–19 but retrospectively reported a complete remission of withdrawal symptoms during that time. When he returned 1 day later than planned on day 19, he did not show signs of withdrawal. On day 22, we increased the buprenorphine dose again. The patient did not show any substantial withdrawal symptoms thereafter. One day after reaching the target dose of buprenorphine 24 mg/d, all full agonists were abruptly and completely stopped at day 29 without any symptoms of opioid withdrawal. The patient has now been on buprenorphine treatment for an on-going period of 7 months, abstaining from any additional substance use. Figure 1 illustrates SOWS scores in relation to daily doses of buprenorphine and combined full agonists. For the latter, we calculated methadone equivalent daily doses by using the following ratio: oral DAM:methadone 8:1.23

Figure 1

Daily buprenorphine dose (mg), full agonist dose (in MEQDD), and SOWS scores of case 2.

Table 2

Opioid doses, withdrawal symptoms, cravings, and mental state in case 2

Discussion

The two case reports illustrate that buprenorphine maintenance can be induced by overlapping with street heroin use or OMT with high-dosed full µ-agonists. Both patients tolerated the induction well and experienced only very mild opioid withdrawal and craving. Twice, the first patient had experienced the conventional method of buprenorphine induction (ie, induction after more than 4 hours since using street heroin and in the presence of clear objective symptoms of withdrawal) as very difficult. She reported substantially fewer symptoms with the Bernese method.

While the duration until stable buprenorphine dosing may be longer than with the conventional method, the Bernese method of overlapping induction may have considerable advantages. It may be helpful for patients fearing withdrawal or experiencing severe symptoms during conventional induction. It may be associated with fewer and less severe opioid withdrawal symptoms. Furthermore, it is no longer necessary to wait for these before induction. In addition to the discomfort, opioid withdrawal may lead to dropout during the induction process. In fact, the slightly better treatment retention with methadone compared to buprenorphine seems to be related to higher dropout rates during the first 2 weeks.9,24 In our experience, some patients are deterred from buprenorphine treatment because they fear these symptoms. Moreover, providers may be reluctant to use buprenorphine due to the complex conventional induction method. With overlapping induction, buprenorphine can be initiated directly, independent of last opioid use and type of full agonist used. This is particularly important considering the repeated cycling in and out of treatment observed in OMT.25

The Bernese method may also be beneficial when a switch to buprenorphine is desired for patients maintained on a full µ-agonist such as methadone, slow-release oral morphine sulfate, or DAM. With the conventional induction method, tapering of the full µ-agonist, for example to 30–40 mg methadone per day, is recommended before buprenorphine is initiated.8 Furthermore, it is again necessary to wait for objective signs of withdrawal.4 Both prerequisites do not apply with the Bernese method: buprenorphine can be increased gradually with overlapping use of the full agonist maintenance dose. Once the target dose is reached, the full agonists can be stopped abruptly. Hess et al26 have previously described a method of switching from doses between 70 and 100 mg methadone, but used transdermal patches and a quicker scheme of dose increases. In our clinical experience, this scheme can also lead to substantial withdrawal symptoms. More research into these methods is necessary to investigate tolerability and symptomatology.

Comparing both our cases, it is noteworthy that the dose increase in case 2 was done slower and in smaller steps. This cautious strategy was chosen for two reasons. First, the patient was on high doses of full µ-agonists, likely increasing the danger of precipitated withdrawal compared to patient 1 who used street heroin containing an unknown, but most probably lower, full µ-agonist dose. Second, as patient 2 had stabilized well during treatment with full µ-agonists, we did not want to jeopardize the improvements by inducing buprenorphine too rapidly. Taken together, our cases can be regarded as representative of the wide spectrum of opioid-dependent persons, from sniffers of street heroin on one hand to users of high doses of full µ-agonists on the other.

Several questions remain open and need to be addressed in systematic studies. The Bernese method should be directly compared to conventional induction with randomized study designs to determine whether it is generally associated with better tolerability. Such studies could also investigate whether there is an impact of the induction process on the outcome of further OMT, in particular cycling in and out of treatment, or whether there are subpopulations of patients for which a specific induction procedure is preferable. Other issues concern the ideal starting dose for buprenorphine, the optimal dose increase scheme, and whether this is influenced by blood levels and type of full µ-agonist used. It is unclear whether there are critical thresholds in buprenorphine dosing that may lead to pharmacodynamic changes. Our second patient was kept on a daily dose of 6 mg buprenorphine for 10 days, because we did not want to increase the dose without medical supervision during his vacation. He experienced the strongest, albeit still mild, symptoms with buprenorphine doses of 3–6 mg.

Likewise, in pre-existing OMT, it is unknown which buprenorphine dose allows cessation of the full µ-agonist without producing opioid withdrawal. This dose is likely determined by the dose of the full agonist used in OMT. Future studies should collect data on blood levels of buprenorphine and full agonists.

Our cases illustrate that overlapping induction of buprenorphine while being on full µ-agonists is feasible. We hope to stimulate more research in this area, which will, ideally, lead to a better tolerable, more patient-oriented induction of buprenorphine treatment, and diversification of opioids in OMT.

Footnotes

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Article information

Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2016; 7: 99–105.

Published online 2016 Jul 20. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S109919

PMCID: PMC4959756

PMID: 27499655

Robert Hämmig,1 Antje Kemter,2 Johannes Strasser,2 Ulrich von Bardeleben,1 Barbara Gugger,1 Marc Walter,2 Kenneth M Dürsteler,2 and Marc Vogel2

1Division of Addiction, University Psychiatric Services Bern, Bern, Switzerland

2Division of Substance Use and Addictive Disorders, University of Basel Psychiatric Hospital, Basel, Switzerland

Correspondence: Marc Vogel, Division of Substance Use and Addictive Disorders, University of Basel Psychiatric Hospital, Wilhelm Klein-Strasse 27, 4012 Basel, Switzerland, Tel +41 61 325 5111, Fax +41 61 325 5583, Email [email protected]

Copyright © 2016 Hämmig et al. This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited

The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed.

Articles from Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation are provided here courtesy of Dove Press

References

1. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD002207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Anchersen K, Clausen T, Gossop M, Hansteen V, Waal H. Prevalence and clinical relevance of corrected QT interval prolongation during methadone and buprenorphine treatment: a mortality assessment study. Addiction. 2009;104:993–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Degenhardt L, Randall D, Hall W, Law M, Butler T, Burns L. Mortality among clients of a state-wide opioid pharmacotherapy program over 20 years: risk factors and lives saved. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Swiss Society of Addiction Medicine (SSAM)Clinical Recommendations for Substitution-assisted Treatment in Opioid Dependence 2012 [Medizinische Empfehlungen für substitutionsgestützte Behandlungen (SGB) bei Opioidabhängigkeit 2012] Mediscope AG, Zurich: Swiss Society of Addiction Medicine; 2013. [Accessed March 30, 2015]. Available from:http://www.ssam.ch/SSAM/sites/default/files/EmpfehlungenSGB_2012_FINAL_05032013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

5. Jasinski DR, Preston KL. Laboratory studies of buprenorphine in opioid abusers. In: Cowan A, Lewis J, editors. Buprenorphine: Combatting Drug Abuse with a Unique Opioid. New York, NY: Wiley-Liss, Inc; 1995. pp. 189–211. [Google Scholar]

6. FDA US Food and Drug Administration . Buprenorphine – Drug Label. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration; 2010. [Accessed November 21, 2015]. Available from:http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/...ormationforPatientsandProviders/UCM191529.pdf. [Google Scholar]

7. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment . Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2004. [Accessed November 30, 2015]. Available from:http://www.buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/Bup_Guidelines.pdf. [Google Scholar]

8. Levin FR, Fischman MW, Connerney I, Foltin RW. A protocol to switch high-dose, methadone-maintained subjects to buprenorphine. Am J Addict. 1997;6:105–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Mattick RP, Ali R, White JM, O’Brien S, Wolk S, Danz C. Buprenorphine versus methadone maintenance therapy: a randomized double-blind trial with 405 opioid-dependent patients. Addiction. 2003;98:441–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Pani PP, Maremmani I, Pirastu R, Tagliamonte A, Gessa GL. Buprenorphine: a controlled clinical trial in the treatment of opioid dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;60:39–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Petitjean S, Stohler R, Déglon JJ, et al. Double-blind randomized trial of buprenorphine and methadone in opiate dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;62:97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Schottenfeld RS, Pakes JR, Oliveto A, Ziedonis D, Kosten TR. Buprenorphine vs methadone maintenance treatment for concurrent opioid dependence and cocaine abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:713–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Comer SD, Walker EA, Collins ED. Buprenorphine/naloxone reduces the reinforcing and subjective effects of heroin in heroin-dependent volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;181:664–675.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Rothman R, Ni Q, Xu H. Buprenorphine: a review of the binding literature. In: Cowan A, Lewis J, editors. Buprenorphine: Combatting Drug Abuse with a Unique Opioid. New York, NY: Wiley-Liss, Inc; 1995. pp. 19–29. [Google Scholar]

15. Bickel WK, Amass L, Crean JP, Badger GJ. Buprenorphine dosing every 1, 2, or 3 days in opioid-dependent patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:111–118.[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Walsh SL, June HL, Schuh KJ, Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Effects of buprenorphine and methadone in methadone-maintained subjects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;119:268–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Resnick RB, Kestenbaum RS, Washton A, Poole D. Naloxone-precipitated withdrawal: a method for rapid induction onto naltrexone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1977;21:409–413.[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Loimer N, Schmid RW, Presslich O, Lenz K. Continuous naloxone administration suppresses opiate withdrawal symptoms in human opiate addicts during detoxification treatment. J Psychiatr Res. 1989;23:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Mendelson J, Jones RT, Welm S, Brown J, Batki SL. Buprenorphine and naloxone interactions in methadone maintenance patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:1095–1101.[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Hämmig R. Einleitung einer Substitutionsbehandlung mit Buprenorphin unter vorübergehender Überlappung mit Heroinkonsum: ein neuer Ansatz (“Berner Methode”). [Induction of a buprenorphine substitution treatment with temporary overlap of heroin use: a new approach (“Bernese Method”)] Suchttherapie. 2010;11:129–132.German. [Google Scholar]

21. Meissner W, Leyendecker P, Mueller-Lissner S, et al. A randomised controlled trial with prolonged-release oral oxycodone and naloxone to prevent and reverse opioid-induced constipation. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:56–64.[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Gossop M. The development of a Short Opiate Withdrawal Scale (SOWS) Addict Behav. 1990;15:487–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Vogel M, Dürsteler-MacFarland KM, Walter M, et al. Prolonged use of benzodiazepines is associated with childhood trauma in opioid-maintained patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;119:93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Lingford-Hughes A, Welch S, Peters L, Nutt D. BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity: recommendations from BAP. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:899–952.[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Nordt C, Vogel M, Dürsteler KM, Stohler R, Herdener M. A comprehensive model of treatment participation in chronic disease allowed prediction of opioid substitution treatment participation in Zurich, 1992–2012. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:1346–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Hess M, Boesch L, Leisinger R, Stohler R. Transdermal buprenorphine to switch patients from higher dose methadone to buprenorphine without severe withdrawal symptoms. Am J Addict. 2011;20:480–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Use of microdoses for induction of

buprenorphine treatment with overlapping opioid use.

Division of Addiction, University

Psychiatric Services

Because induction of buprenorphine is a difficult experience, due to withdrawal

symptoms. Furthermore, tapering of the full agonist bears the risk of relapse to illicit opioid use.

Cases: We present two cases of successful initiation of buprenorphine treatment with the

Bernese method, ie, gradual induction overlapping with full agonist use. The first patient began

buprenorphine with overlapping street heroin use after repeatedly experiencing relapse, with-

drawal, and trauma reactivation symptoms during conventional induction. The second patient

was maintained on high doses of diacetylmorphine (ie, pharmaceutical heroin) and methadone

during induction. Both patients tolerated the induction procedure well and reported only mild

withdrawal symptoms.

Discussion: Overlapping induction of buprenorphine maintenance treatment with full µ-opioid

receptor agonist use is feasible and may be associated with better tolerability and acceptability

in some patients compared to the conventional method of induction.

Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation

Dove Press

Use of microdoses for induction of buprenorphine treatment with overlapping full opioid agonist use: the Bernese method

Robert Hämmig, Antje Kemter, [...], and Marc Vogel

Additional article information

Abstract

Background

Buprenorphine is a partial µ-opioid receptor agonist used for maintenance treatment of opioid dependence. Because of the partial agonism and high receptor affinity, it may precipitate withdrawal symptoms during induction in persons on full µ-opioid receptor agonists. Therefore, current guidelines and drug labels recommend leaving a sufficient time period since the last full agonist use, waiting for clear and objective withdrawal symptoms, and reducing pre-existing full agonist therapies before administering buprenorphine. However, even with these precautions, for many patients the induction of buprenorphine is a difficult experience, due to withdrawal symptoms. Furthermore, tapering of the full agonist bears the risk of relapse to illicit opioid use.

Cases

We present two cases of successful initiation of buprenorphine treatment with the Bernese method, ie, gradual induction overlapping with full agonist use. The first patient began buprenorphine with overlapping street heroin use after repeatedly experiencing relapse, withdrawal, and trauma reactivation symptoms during conventional induction. The second patient was maintained on high doses of diacetylmorphine (ie, pharmaceutical heroin) and methadone during induction. Both patients tolerated the induction procedure well and reported only mild withdrawal symptoms.

Discussion

Overlapping induction of buprenorphine maintenance treatment with full µ-opioid receptor agonist use is feasible and may be associated with better tolerability and acceptability in some patients compared to the conventional method of induction.

Keywords: subutex, suboxone, heroin, opiate, substitution

Introduction

Buprenorphine is a partial µ-opioid agonist and κ-opioid antagonist used for maintenance treatment of opioid dependence (OMT). It is as effective as methadone in suppressing opioid use and is slightly less effective in retaining patients in treatment.1 Buprenorphine has potential advantages over methadone, including a lower risk of overdose due to the partial agonism and the associated “low ceiling effect” for respiratory depression, fewer pharmaceutical interactions, and absence of corrected QT interval (QTc)-prolongation.2–4However, because buprenorphine replaces other opioids at the µ-receptor due to its high affinity, the partial agonism at the µ-opioid receptor may precipitate severe withdrawal in persons regularly using opioids.5Therefore, guidelines on buprenorphine induction in OMT and drug labels recommend consideration of the nature of opioid dependence (ie, long- or short-acting opioid), its degree, and the time since last opioid use:4,6,7 physicians should leave sufficient time between last use of opioid agonist and buprenorphine. This time depends on the opioid used and ranges between 4 (heroin) and 36–48 hours (methadone). Moreover, waiting for observable opioid withdrawal symptoms before starting buprenorphine is recommended. A switch of the substitute from methadone to buprenorphine requires prior tapering of methadone to a daily dose of 30–40 mg.8

Clinical experience shows that despite these precautions, the induction of buprenorphine can precipitate severe opioid withdrawal. In addition to the discomfort, this may lead to treatment dropout or relapse with full opioid agonists. Precipitated withdrawal and the complicated induction process may result in differences between buprenorphine and methadone with regard to treatment retention in the first 2 weeks.9

Between 40% and 60% of buprenorphine-maintained persons concomitantly use full µ-receptor agonists.10–12 According to patients’ accounts and experimental studies, this use is not associated with opioid withdrawal but attenuated subjective opioid effects such as euphoria.13 The attenuation persists for some days after termination of buprenorphine use. The likely explanation is the higher opioid receptor binding capacity of buprenorphine. Other opioid agonists and their active metabolites can replace only a small fraction of buprenorphine at the receptor. Moreover, because of its low dissociation constant, buprenorphine separates slowly from the receptor once it is bound.14 The slow association/dissociation kinetics allow for 72-hour dosing intervals in buprenorphine treatment.4,15 Because of the high µ-opioid receptor affinity, buprenorphine can replace a full µ-agonist at the receptor while at the same time providing less µ-opioid effects.16

Resnick et al17 showed that repetitive administration of the µ-antagonist naloxone quickly leads to a maximum of withdrawal symptoms that decline afterward despite continued naloxone application. This phenomenon was used in the 1980s in the development of rapid withdrawal procedures.18 Furthermore, it was shown that a very small dose of 0.2 mg buprenorphine intravenous (iv) did not produce opioid withdrawal in methadone-maintained individuals.19

From this, we developed the following hypotheses: 1) Repetitive administration of very small buprenorphine doses with sufficient dosing intervals (eg, 12 hours) should not precipitate opioid withdrawal. 2) Because of the long receptor binding time, buprenorphine will accumulate at the receptor. 3) Over time, an increasing amount of a full µ-agonist will be replaced by buprenorphine at the opioid receptor.

Hence, overlapping induction of buprenorphine with ongoing use of street heroin or maintenance on high doses of a full µ-agonist should be possible without precipitating severe opioid withdrawal. We present two cases in which we tested this procedure, termed the Bernese method. In both patients, we used sublingual buprenorphine, as the buprenorphine/naloxone combination is not available in Switzerland. We first introduced this method in 2010, and described the initial treatment of the first case in German.20 The second case has never been published before. We have successfully applied the Bernese method in a number of patients since. Clinical treatment was conducted in agreement with the patients, and both patients consented to the publication of their data in anonymized form.

Case 1

The patient grew up in an unremarkable middle-class family. At the age of 12, she was sexually abused and developed post-traumatic stress disorder. At the age of 15, she began using various substances (psilocybin, 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine, cocaine, cannabis, and, sporadically, heroin). At the age of 18, she experienced a major depressive episode with a suicide attempt. She then started suffering from bulimia, which remitted at age 23.

Preceding a job-related stay in Central America, she used heroin for several weeks. During the stay, she was unable to obtain heroin and began using crack-cocaine, quickly developing a severe dependence. Back in Switzerland, she successfully managed to stop crack-cocaine, but reinitiated heroin use. After several months, she opted for buprenorphine treatment but experienced the induction-associated symptoms as very stressful.

She stabilized during treatment, tapered buprenorphine and abstained from opioids for several months before initiating sporadic use of heroin again. At the age of 30, when she entered our outpatient treatment, she sniffed 3 g of street heroin daily.

Conventional induction

The patient was ordered to return in the morning. She had then abstained from heroin for more than 8 hours and showed distinct symptoms of withdrawal (rhinorrhea, mydriasis, and stomach cramps).

Buprenorphine was started at 0.4 mg sublingually, and the same dose was administered four times with an interval of 30 minutes. Starting with the first and increasing with each further administration, she felt worse and suffered from diarrhea. She experienced trauma-related flashbacks and showed severe anxiety and dissociative thinking. Her state did not improve with two further doses of 8 mg buprenorphine. We then administered 50 mg of promazine po, which brought some relief, and after 8 hours of surveillance she had improved sufficiently to return home.

Bernese method

After 2 weeks, the patient stopped taking buprenorphine and reinitiated sniffed heroin use. A week later, she presented herself again with the wish for buprenorphine treatment, but was afraid of being unable to tolerate the induction process and the related symptoms. We suggested overlapping buprenorphine induction with the Bernese method (ie, start with a low dose of 0.2 mg buprenorphine overlapping with heroin use, small daily dose increases, and abrupt cessation of heroin use at sufficient dose). Furthermore, we offered her the support of a physician (via text message) to flexibly adapt dosing. Buprenorphine dosing and use of street heroin were noted (Table 1). The patient tolerated this induction process much better than the conventional induction.

Table 1

Buprenorphine dosing and use of street heroin in case 1

She was stable with 12 mg/d buprenorphine. Throughout further treatment she stopped buprenorphine several times, used heroin, and afterward reinitiated buprenorphine treatment with the Bernese method. However, after these short disruptions, she increased buprenorphine dosing more rapidly. She then developed a major depressive episode and was started on 20 mg/d escitalopram and psychotherapy. With this treatment, she stabilized further and abstained from heroin for 2.5 years.

Because of the desire for complete abstinence, she then wanted to stop buprenorphine and initiate naltrexone treatment to reduce opioid craving. However, she was worried about the first week after cessation of buprenorphine, where naltrexone should not be administered according to the drug label.

Overlapping induction of a full antagonist

We assumed that naltrexone could be initiated analogous to the overlapping induction of buprenorphine. Preliminary data suggest that very low naltrexone doses during µ-agonist treatment may not be associated with reduced analgesic efficacy.21However, naltrexone tablets available in Switzerland contain a rather large dose of 50 mg drug. After tapering of buprenorphine to 2 mg/d, the patient started with small amounts of naltrexone scratched off from a tablet and increased the dose daily. She did not develop any withdrawal symptoms or craving, stopped buprenorphine, and increased naltrexone to 25 mg/d. After several months, she stopped naltrexone and has since been abstinent for an ongoing period of 3 years and 3 months.

Case 2

After using heroin for several years and unsuccessful treatment attempts with methadone, the patient entered heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) at the age of 49. In addition to heroin dependence, he fulfilled International Classification of Diseases-10 criteria for cocaine and tobacco dependence. He suffered from mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic hepatitis C-infection, and recurrent thrombosis due to groin injection. Furthermore, the patient had a long history of substance-related crime and imprisonment. Throughout 6 years in HAT, he completely stopped using street heroin, reduced cocaine use to once per month, and entered a job rehabilitation program. At this point, he received 200 mg diacetylmorphine (DAM; ie, pharmaceutical heroin) iv twice daily, and 40 mg of methadone to avoid nighttime withdrawal symptoms. Because he wanted to stop iv injections, iv DAM was switched to oral tablets at the equivalent dose of 400 mg twice daily. After another 2 months without using nonprescribed opioids, the patient desired a less rigid therapeutic setting (HAT entails twice daily medication dispensing 365 days per year). We suggested switching to buprenorphine. Because of fears that the guideline-recommended reduction of the full agonist dose prior to switching might lead to a destabilization, we suggested induction with the Bernese method.

Overlapping induction of buprenorphine with maintenance on full µ-agonists

At first administration of buprenorphine, the patient had been on a stable oral maintenance dose of 40 mg methadone and 800 mg DAM per day for 2 months. It is important to note that we did not grant take-home dosages for DAM tablets, but substituted these with methadone. The patient received methadone instead of DAM when he could not attend on-site dispensing. He completed the short opioid withdrawal scale (SOWS) daily. The SOWS is a ten-item questionnaire rating withdrawal symptoms on a scale of 0–3, yielding a maximum score of 30.22 Another question on opiate craving answered likewise was added. Furthermore, every third day the patient completed visual analog scales related to general mental state and feeling stressed, relaxed, and nervous.

We began with a dose of 0.2 mg buprenorphine sublingually, which was well tolerated. The next day, the dose was increased to 0.4 mg twice daily. We decided to dose twice daily in the beginning as the effect of buprenorphine is shorter at lower doses and switched to once-daily dosing at 2 mg/d. Buprenorphine was principally increased by 0.4 mg/d up to a dose of 3.4 mg, then we increased the daily dose by 20%–30%. The patient tolerated buprenorphine induction very well but reported mild opioid withdrawal symptoms on day 8 at 3 mg/d and day 11 at 4.8 mg/d (Table 2). At 6 mg/d on day 14, the patient went on a 5-day vacation and was switched to 180 mg/d methadone (as DAM tablets were not available as take-home medication), while the buprenorphine dose remained unchanged. During days 13–16, he reported slightly stronger withdrawal symptoms, although they were still mild to moderate (maximum score of 7 in the SOWS). Days 15 and 16 were the only days during induction on which he reported any opiate craving (moderate). Unfortunately, he did not complete the SOWS on days 17–19 but retrospectively reported a complete remission of withdrawal symptoms during that time. When he returned 1 day later than planned on day 19, he did not show signs of withdrawal. On day 22, we increased the buprenorphine dose again. The patient did not show any substantial withdrawal symptoms thereafter. One day after reaching the target dose of buprenorphine 24 mg/d, all full agonists were abruptly and completely stopped at day 29 without any symptoms of opioid withdrawal. The patient has now been on buprenorphine treatment for an on-going period of 7 months, abstaining from any additional substance use. Figure 1 illustrates SOWS scores in relation to daily doses of buprenorphine and combined full agonists. For the latter, we calculated methadone equivalent daily doses by using the following ratio: oral DAM:methadone 8:1.23

Figure 1

Daily buprenorphine dose (mg), full agonist dose (in MEQDD), and SOWS scores of case 2.

Table 2

Opioid doses, withdrawal symptoms, cravings, and mental state in case 2

Discussion

The two case reports illustrate that buprenorphine maintenance can be induced by overlapping with street heroin use or OMT with high-dosed full µ-agonists. Both patients tolerated the induction well and experienced only very mild opioid withdrawal and craving. Twice, the first patient had experienced the conventional method of buprenorphine induction (ie, induction after more than 4 hours since using street heroin and in the presence of clear objective symptoms of withdrawal) as very difficult. She reported substantially fewer symptoms with the Bernese method.

While the duration until stable buprenorphine dosing may be longer than with the conventional method, the Bernese method of overlapping induction may have considerable advantages. It may be helpful for patients fearing withdrawal or experiencing severe symptoms during conventional induction. It may be associated with fewer and less severe opioid withdrawal symptoms. Furthermore, it is no longer necessary to wait for these before induction. In addition to the discomfort, opioid withdrawal may lead to dropout during the induction process. In fact, the slightly better treatment retention with methadone compared to buprenorphine seems to be related to higher dropout rates during the first 2 weeks.9,24 In our experience, some patients are deterred from buprenorphine treatment because they fear these symptoms. Moreover, providers may be reluctant to use buprenorphine due to the complex conventional induction method. With overlapping induction, buprenorphine can be initiated directly, independent of last opioid use and type of full agonist used. This is particularly important considering the repeated cycling in and out of treatment observed in OMT.25

The Bernese method may also be beneficial when a switch to buprenorphine is desired for patients maintained on a full µ-agonist such as methadone, slow-release oral morphine sulfate, or DAM. With the conventional induction method, tapering of the full µ-agonist, for example to 30–40 mg methadone per day, is recommended before buprenorphine is initiated.8 Furthermore, it is again necessary to wait for objective signs of withdrawal.4 Both prerequisites do not apply with the Bernese method: buprenorphine can be increased gradually with overlapping use of the full agonist maintenance dose. Once the target dose is reached, the full agonists can be stopped abruptly. Hess et al26 have previously described a method of switching from doses between 70 and 100 mg methadone, but used transdermal patches and a quicker scheme of dose increases. In our clinical experience, this scheme can also lead to substantial withdrawal symptoms. More research into these methods is necessary to investigate tolerability and symptomatology.

Comparing both our cases, it is noteworthy that the dose increase in case 2 was done slower and in smaller steps. This cautious strategy was chosen for two reasons. First, the patient was on high doses of full µ-agonists, likely increasing the danger of precipitated withdrawal compared to patient 1 who used street heroin containing an unknown, but most probably lower, full µ-agonist dose. Second, as patient 2 had stabilized well during treatment with full µ-agonists, we did not want to jeopardize the improvements by inducing buprenorphine too rapidly. Taken together, our cases can be regarded as representative of the wide spectrum of opioid-dependent persons, from sniffers of street heroin on one hand to users of high doses of full µ-agonists on the other.

Several questions remain open and need to be addressed in systematic studies. The Bernese method should be directly compared to conventional induction with randomized study designs to determine whether it is generally associated with better tolerability. Such studies could also investigate whether there is an impact of the induction process on the outcome of further OMT, in particular cycling in and out of treatment, or whether there are subpopulations of patients for which a specific induction procedure is preferable. Other issues concern the ideal starting dose for buprenorphine, the optimal dose increase scheme, and whether this is influenced by blood levels and type of full µ-agonist used. It is unclear whether there are critical thresholds in buprenorphine dosing that may lead to pharmacodynamic changes. Our second patient was kept on a daily dose of 6 mg buprenorphine for 10 days, because we did not want to increase the dose without medical supervision during his vacation. He experienced the strongest, albeit still mild, symptoms with buprenorphine doses of 3–6 mg.

Likewise, in pre-existing OMT, it is unknown which buprenorphine dose allows cessation of the full µ-agonist without producing opioid withdrawal. This dose is likely determined by the dose of the full agonist used in OMT. Future studies should collect data on blood levels of buprenorphine and full agonists.

Our cases illustrate that overlapping induction of buprenorphine while being on full µ-agonists is feasible. We hope to stimulate more research in this area, which will, ideally, lead to a better tolerable, more patient-oriented induction of buprenorphine treatment, and diversification of opioids in OMT.

Footnotes

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Article information

Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2016; 7: 99–105.

Published online 2016 Jul 20. doi: 10.2147/SAR.S109919

PMCID: PMC4959756

PMID: 27499655

Robert Hämmig,1 Antje Kemter,2 Johannes Strasser,2 Ulrich von Bardeleben,1 Barbara Gugger,1 Marc Walter,2 Kenneth M Dürsteler,2 and Marc Vogel2

1Division of Addiction, University Psychiatric Services Bern, Bern, Switzerland

2Division of Substance Use and Addictive Disorders, University of Basel Psychiatric Hospital, Basel, Switzerland

Correspondence: Marc Vogel, Division of Substance Use and Addictive Disorders, University of Basel Psychiatric Hospital, Wilhelm Klein-Strasse 27, 4012 Basel, Switzerland, Tel +41 61 325 5111, Fax +41 61 325 5583, Email [email protected]

Copyright © 2016 Hämmig et al. This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited

The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/). By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed.

Articles from Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation are provided here courtesy of Dove Press

References

1. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD002207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Anchersen K, Clausen T, Gossop M, Hansteen V, Waal H. Prevalence and clinical relevance of corrected QT interval prolongation during methadone and buprenorphine treatment: a mortality assessment study. Addiction. 2009;104:993–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Degenhardt L, Randall D, Hall W, Law M, Butler T, Burns L. Mortality among clients of a state-wide opioid pharmacotherapy program over 20 years: risk factors and lives saved. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Swiss Society of Addiction Medicine (SSAM)Clinical Recommendations for Substitution-assisted Treatment in Opioid Dependence 2012 [Medizinische Empfehlungen für substitutionsgestützte Behandlungen (SGB) bei Opioidabhängigkeit 2012] Mediscope AG, Zurich: Swiss Society of Addiction Medicine; 2013. [Accessed March 30, 2015]. Available from:http://www.ssam.ch/SSAM/sites/default/files/EmpfehlungenSGB_2012_FINAL_05032013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

5. Jasinski DR, Preston KL. Laboratory studies of buprenorphine in opioid abusers. In: Cowan A, Lewis J, editors. Buprenorphine: Combatting Drug Abuse with a Unique Opioid. New York, NY: Wiley-Liss, Inc; 1995. pp. 189–211. [Google Scholar]

6. FDA US Food and Drug Administration . Buprenorphine – Drug Label. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration; 2010. [Accessed November 21, 2015]. Available from:http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/...ormationforPatientsandProviders/UCM191529.pdf. [Google Scholar]

7. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment . Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2004. [Accessed November 30, 2015]. Available from:http://www.buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/Bup_Guidelines.pdf. [Google Scholar]

8. Levin FR, Fischman MW, Connerney I, Foltin RW. A protocol to switch high-dose, methadone-maintained subjects to buprenorphine. Am J Addict. 1997;6:105–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Mattick RP, Ali R, White JM, O’Brien S, Wolk S, Danz C. Buprenorphine versus methadone maintenance therapy: a randomized double-blind trial with 405 opioid-dependent patients. Addiction. 2003;98:441–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Pani PP, Maremmani I, Pirastu R, Tagliamonte A, Gessa GL. Buprenorphine: a controlled clinical trial in the treatment of opioid dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;60:39–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Petitjean S, Stohler R, Déglon JJ, et al. Double-blind randomized trial of buprenorphine and methadone in opiate dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;62:97–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Schottenfeld RS, Pakes JR, Oliveto A, Ziedonis D, Kosten TR. Buprenorphine vs methadone maintenance treatment for concurrent opioid dependence and cocaine abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:713–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Comer SD, Walker EA, Collins ED. Buprenorphine/naloxone reduces the reinforcing and subjective effects of heroin in heroin-dependent volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;181:664–675.[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Rothman R, Ni Q, Xu H. Buprenorphine: a review of the binding literature. In: Cowan A, Lewis J, editors. Buprenorphine: Combatting Drug Abuse with a Unique Opioid. New York, NY: Wiley-Liss, Inc; 1995. pp. 19–29. [Google Scholar]

15. Bickel WK, Amass L, Crean JP, Badger GJ. Buprenorphine dosing every 1, 2, or 3 days in opioid-dependent patients. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:111–118.[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Walsh SL, June HL, Schuh KJ, Preston KL, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML. Effects of buprenorphine and methadone in methadone-maintained subjects. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;119:268–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Resnick RB, Kestenbaum RS, Washton A, Poole D. Naloxone-precipitated withdrawal: a method for rapid induction onto naltrexone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1977;21:409–413.[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Loimer N, Schmid RW, Presslich O, Lenz K. Continuous naloxone administration suppresses opiate withdrawal symptoms in human opiate addicts during detoxification treatment. J Psychiatr Res. 1989;23:81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Mendelson J, Jones RT, Welm S, Brown J, Batki SL. Buprenorphine and naloxone interactions in methadone maintenance patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:1095–1101.[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Hämmig R. Einleitung einer Substitutionsbehandlung mit Buprenorphin unter vorübergehender Überlappung mit Heroinkonsum: ein neuer Ansatz (“Berner Methode”). [Induction of a buprenorphine substitution treatment with temporary overlap of heroin use: a new approach (“Bernese Method”)] Suchttherapie. 2010;11:129–132.German. [Google Scholar]

21. Meissner W, Leyendecker P, Mueller-Lissner S, et al. A randomised controlled trial with prolonged-release oral oxycodone and naloxone to prevent and reverse opioid-induced constipation. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:56–64.[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Gossop M. The development of a Short Opiate Withdrawal Scale (SOWS) Addict Behav. 1990;15:487–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Vogel M, Dürsteler-MacFarland KM, Walter M, et al. Prolonged use of benzodiazepines is associated with childhood trauma in opioid-maintained patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;119:93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Lingford-Hughes A, Welch S, Peters L, Nutt D. BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity: recommendations from BAP. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:899–952.[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Nordt C, Vogel M, Dürsteler KM, Stohler R, Herdener M. A comprehensive model of treatment participation in chronic disease allowed prediction of opioid substitution treatment participation in Zurich, 1992–2012. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68:1346–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Hess M, Boesch L, Leisinger R, Stohler R. Transdermal buprenorphine to switch patients from higher dose methadone to buprenorphine without severe withdrawal symptoms. Am J Addict. 2011;20:480–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]