Psychedelic-assisted therapy is transforming the way we think about mental health care

How mushrooms, LSD, MDMA, and ketamine could help treat mental illnesses.

by Stav Dimitropoulos | SELF | 24 May 2022

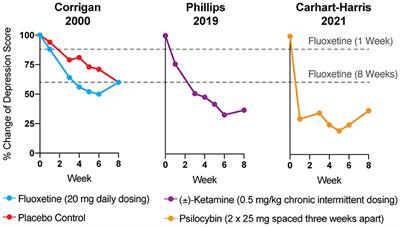

Since the 1970s and the barrage of scientific studies that have explored the therapeutic effects of psychedelics, the mind-bending substances have exhibited immense promise in transforming how we think about mental health care, most notably when it comes to understanding how people can heal from depression, anxiety, addiction, and

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

These substances, broadly thought of as psychedelic drugs, include LSD, psilocybin, and MDMA. All three of them are Schedule I drugs in the U.S., which is the federal government’s most restrictive classification for drugs, indicating that they have a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical uses. Not only does this scheduling make these drugs illegal at federal level, but it has also historically restricted the research that experts can do with them.

But now the global scientific community is going through something of a “psychedelic renaissance.” And research continues to show that, when used in controlled therapy settings, these substances have the potential to profoundly alter the future of mental health care.

What does psychedelic therapy actually look like?

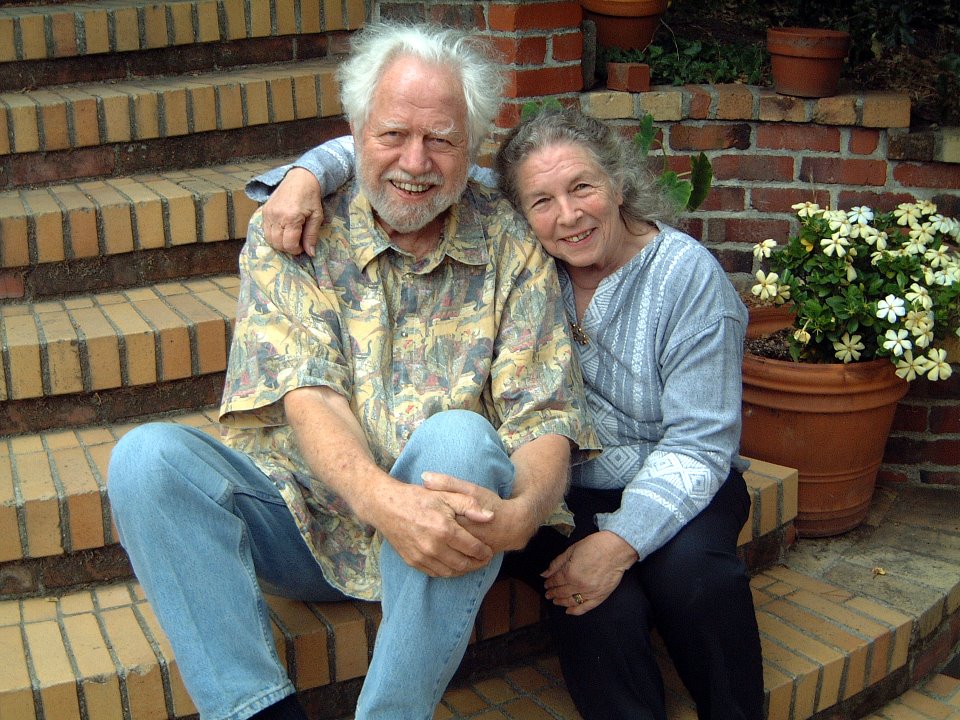

“We have had success in demonstrating that psychedelics tackle depression as well as the mental distress associated with life-threatening illnesses, addictions, and more,” Alan Davis, PhD, director of the

Center for Psychedelic Drug Research and Education at Ohio State University, tells SELF.

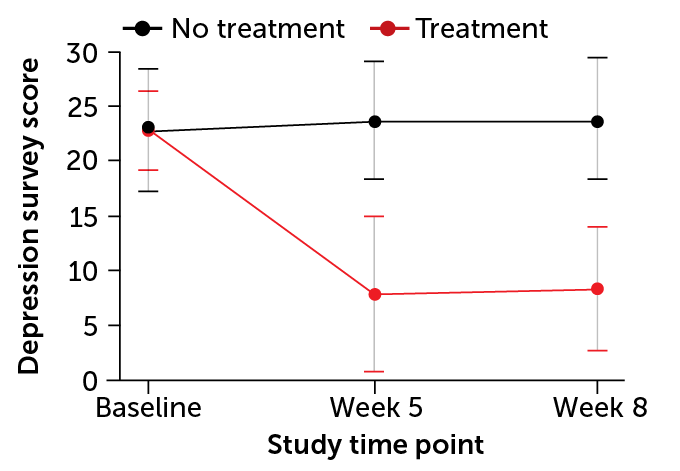

In a 2022 study published by Dr. Davis and his colleagues in the

Journal of Psychopharmacology, 24 people with moderate to severe depression received two doses of psilocybin, spaced two weeks apart, in combination with supportive talk therapy, either immediately after a screening or after an eight-week wait. The researchers followed up with the participants intermittently over a year following their second dose—and the results were exciting: 58% of the people in the study achieved remission from their depression, while 75% of the people in the study responded to the treatment with dramatically-reduced

depression symptoms.

“This is pretty remarkable considering that the best treatments we have right now require daily medication for the rest of your life or extensive psychotherapy, and even then they’re not as effective,” Dr. Davis says.

This research follows a

similarly-designed November 2020 study from some members of the same scientific team. The findings were equally promising: After everyone received psilocybin-assisted therapy, 71 percent of the participants (17 people) were in remission from depression four weeks later.

While both of these studies are encouraging, it’s worth noting that they include relatively small sample groups (although they are generally on par with other studies in this area), and further research that includes diverse groups of people will be needed to truly understand the benefits of psilocybin-assisted therapy, as well as other psychedelic-assisted therapies, on a larger scale.

With that said, in both experiments the participants didn’t just take a capsule and watch their depression vanish into thin air. The interventions outlined a model for a psychedelic-assisted therapeutic approach, which requires a structured and supervised setting and well-trained providers.

In the 2022 study, for example, participants were required to first have at least six hours of preparatory meetings with two trained credentialed facilitators. After that they underwent two day-long sessions with psilocybin administration, two weeks apart. During the sessions, in which a participant lies on a couch with headphones on while listening to music, the facilitators are on hand to respond to their needs. After the sessions the participant has another two to three hours of follow-up meetings with the facilitators.

The patients in the 2020 study also received a total of 11 hours of

supportive psychotherapy alongside the drug treatment to make sense of the experience and move forward with their lives. The entire treatment process lasted about eight weeks. This protocol is similar—but not totally identical—to that of other psychedelic-assisted therapy studies. But what they all have in common is extensive access to support before, during, and after the drug experience.

How does psychedelic therapy work?

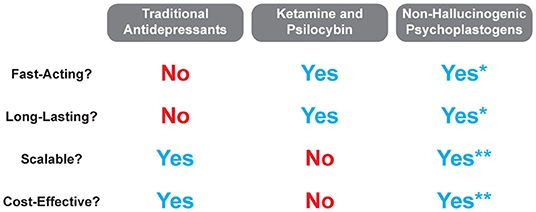

For many people antidepressants can be an effective way to treat the symptoms of depression, various

forms of anxiety, and other mental health issues, especially when used alongside talk therapies. But these medications often need to be taken for years or even a person’s entire lifetime, and they can come with a risk of potential side effects, such as sleep issues, agitation, loss of appetite, and a reduced desire for sex, among others.

Psychedelic-assisted therapy appears to be effective in the long term after a few short, intense weeks to months of treatment; some

research suggests therapeutic effects can begin after a single session. These drugs can cause side effects, too, such as nausea, increased heart rate, and hallucinations (depending on the substance). But when the drugs are used in this short-term way, those side effects generally occur during or shortly after the drug experience, which is one reason why supervision and support during that time are so essential.

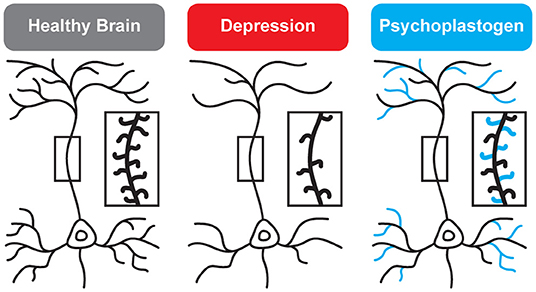

Like antidepressants, psychedelics have effects on specific neurotransmitters,

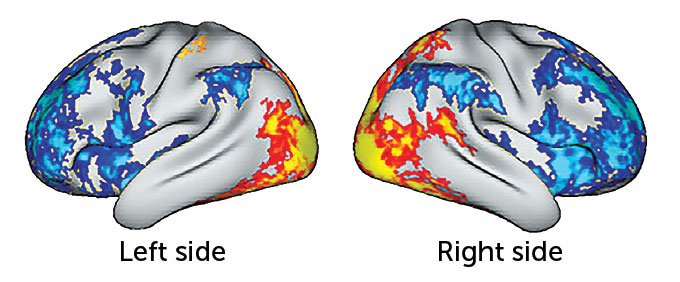

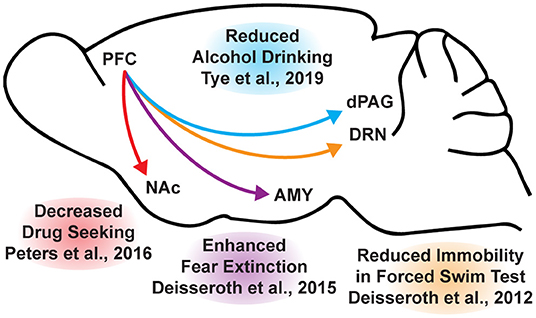

including serotonin. But experts think psychedelics’ effectiveness is also due to their ability to reconfigure our neural architecture.

“For instance, brain imaging studies show that, over time, neurons in the brain’s prefrontal cortex atrophy in people with depression. But the controlled use of psychedelics may actually change this,” Linda Strause, PhD, professor of human nutrition at the University of California San Diego and an executive in the drug development industry, tells SELF.

"Psychedelics may stimulate the growth of new neurons as well as new connections between them, which suggests they may be able to help treat the symptoms of depression, PTSD, and other mental health issues," she says.

“Hallucinogenic substances also have the ability to

reset our default mode network (DMN) immediately and for long periods of time,”

David J. Mokler, PhD, a neuropharmacologist, professor emeritus at the University of New England, and advisor at psychedelic biotechnology company Havn Life, tells SELF.

"The DMN is a network of connected parts of the brain that are active when you’re not specifically thinking about or working on anything, such as when you’re daydreaming. Altering the way the DMN functions seems to help long-term with depression, particularly the depression that doesn’t seem to respond to the classic treatments we usually give,” Dr. Mokler says.

These biological changes likely reflect the psychological—and sometimes spiritual—changes that can occur during the psychedelic experience.

“When people take psychedelics, they often have spiritual experiences and a new awareness of their emotions, relationships, and career, and it is this combination that seems to bring the most results,” Dr. Davis says.

"In this way, psychedelic therapy can offer someone the chance to experience a radically different perspective on their life, one that might help them realize important aspects of their environment, relationships, or thinking patterns that could be contributing to their depression, for instance."

However, it’s crucial to understand that it’s not just the drugs that are likely to be helpful; the follow-up sessions with facilitators are also important so that patients can

“integrate” their experience, as some researchers put it, and draw productive meaning from what they explored while in their psychedelic state.

Various drugs have psychoactive properties—but which ones hold the most therapeutic potential?

Ketamine

Some experts hesitate to classify ketamine as a genuine psychedelic, Dr. Davis included. Ketamine is an injectable, short-acting anesthetic that comes in a clear liquid or white powder, but it’s lumped in with psychedelic drugs due to its possible hallucinogenic effects. That’s why it’s sometimes referred to as a “dissociative anesthetic”—it can warp sensory perceptions like sight and sound and make a person feel disconnected from their surroundings or detached from feelings like pain.

Researchers theorize that ketamine influences the activity of glutamate, an abundant neurotransmitter in the central nervous system that is thought to have significant effects on various health conditions, including mood disorders like depression, but more research is needed to understand the correlation.

As a Schedule III non-narcotic substance, ketamine is the only drug under the psychedelics umbrella with legalized, medically-accepted use at the time of publication. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

first approved esketamine, a

ketamine-based nasal spray, for treatment-resistant depression in 2019. That’s the caveat: It’s only been approved for that specific mental health condition. Ketamine-assisted therapy used to treat other mental health issues—such as PTSD, which often triggers depression—would be

considered “off-label” use by the FDA. Off-label means a health care provider prescribes an approved drug to treat a condition it was not specifically approved to treat, prescribes the drug in a different dosage than what has been approved, or administers the drug in a different way than it has been approved. While ketamine’s off-label use concerns some experts for various reasons, including patient safety, the practice continues to be incredibly common in the medical community as a whole—one in five prescriptions are considered to be off-label use, according to the

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Currently, ketamine is the

focus of at least 99 studies for the treatment of mental health conditions with a heavy focus on depression and pain-related health issues like chronic headaches. Emerging research continues to explore ketamine’s therapeutic potential for conditions like

PTSD,

social anxiety, and

obsessive-compulsive disorder as well—all of which hold potentially exciting developments for ketamine’s future use.

MDMA

MDMA, which is classified as both a stimulant and a psychedelic, became popular in the rave and electronic dance music culture of the 1980s and 1990s. It’s commonly sourced from safrole oil, an essential oil derived from the sassafras tree, which is an aromatic tree endemic in North America, and it’s most commonly distributed in tablet form.

The drug’s signature effects are feelings of emotional connectedness, closeness, warmth, and empathy, which tend to last for three to six hours. MDMA can also cause an increased heart rate, sweating, blurred vision, restlessness, and (in rare cases) a life-threatening increase in body temperature.

Much of the research looking at the therapeutic potential of MDMA-assisted therapy comes from

MAPS, a nonprofit research and educational organization founded in 1986 that is committed to furthering the understanding of psychedelics and marijuana; it is known for its

MDMA-assisted therapy training program for eligible mental health professionals. In 2021, MAPS finalized the first

Phase 3 trial of the use of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for people with PTSD. The study showed that over 67% of the participants who received MDMA-assisted therapy no longer met the criteria for PTSD. The organization’s protocol

received a Breakthrough Therapy designation from the FDA in 2017, meaning the treatment has shown the potential to be more effective compared to current medications used to treat severe PTSD.

While most of the clinical trials focused on MDMA are further exploring the drug’s impact on people with PTSD, experts are also investigating its potential in treating other mental health issues, such as

anxiety associated with a life-threatening illness.

Psilocybin

Hallucinogenic magic mushrooms have an ancient history. Even

Stone Age artists in Africa and Europe, pre-Columbian sculptors across North, Central, and South America, and

ancient populations of the Sahara desert depicted what experts believe to be mushrooms in their art.

Today, psilocybin, the chemical compound derived from certain dried or fresh hallucinogenic mushrooms, has been both decriminalized and legalized for therapeutic use

in Oregon only. Starting in January 2023, the state will make the drug available in qualified settings with the oversight of a trained physician and therapist, Dr. Strause says.

Researchers believe that, like other psychedelics, psilocybin mingles with a certain serotonin receptor (5-HT2A), which sets off a “mystical-like hallucinatory effect.” Psilocybin’s effects typically hit within 20 minutes and last for about six hours, and the drug can cause mood changes and visual and auditory hallucinations, as well as nausea, vomiting, sleepiness, and muscle weakness. Large doses, in particular, may elicit feelings of panic.

In recent investigational studies, researchers have found psilocybin-assisted therapy to be helpful for people with

treatment-resistant depression as well as

depression and anxiety in people with life-threatening diseases. And in the past few years, the FDA gave two

psilocybin-assisted therapy programs Breakthrough Therapy status.

LSD

First accidentally synthesized by Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann in 1938, LSD is a potent, perception-changing synthetic chemical. It’s created from the lysergic acid found in ergot, which is a fungus that infects rye. (And yes, the CIA did investigate LSD as a

potential psychological weapon during the Cold War.) An LSD experience can typically last up to 12 hours, in which a person may experience hallucinations, distortions in sensory perceptions and time, and positive or negative changes in mood. It can also cause physical side effects like higher or lower body temperatures, sweating, dry mouth, high blood pressure, or muscle tension, among others.

Researchers have been looking at LSD’s potential to help people with mental health issues since the 1950s, but those studies

stalled when the federal government prohibited LSD, largely because it became inextricably linked to the 1960s counterculture. However, recent small studies looking at LSD-assisted therapy have found that it has potential benefits for people dealing with

alcoholism and

anxiety in people with life-threatening diseases. In January 2022, the FDA

cleared a Phase 2(b) clinical trial of a generalized anxiety disorder treatment that uses a “

pharmacologically optimized form of LSD.”

Will psychedelic-assisted therapy be accessible in the future?

As research continues, various forms of psychedelic-assisted therapy could eventually reach FDA approval. But like any modern medicine, accessibility will be a huge concern. Here are a few potential challenges the scientific community is grappling with—and how experts are thinking about making these innovative therapies more available to everyone.

Drug scheduling limitations

Most drugs under the psychedelic umbrella still have

Schedule I status, which “imposes a ceiling on many policy recommendations,” especially when it comes to federal funding, researchers who authored a 2021 paper in the journal

Nature Medicine argue.

“Legislation is the biggest obstacle,” Dr. Davis says.

“It won’t be until we have FDA approval and/or other legislative changes that we will be able to see advances and the destigmatization of psychedelics.”

Rescheduling drugs isn’t an easy process, but some advocacy groups are trying to work toward just that. Experts especially have their eyes on psilocybin, since it’s naturally derived from fungi, has a low toxicity risk, has a low potential for dependence, and is already decriminalized in several other countries. One global coalition—the

International Therapeutic Psilocybin Rescheduling Initiative—is advocating to reschedule psilocybin under the

United Nations 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances, an international treaty that aims to limit the abuse of certain psychoactive drugs. This rescheduling would help nix psilocybin’s international research restrictions, potentially opening the doors for its medical use. In the U.S., anyone is able to petition the Drug Enforcement Administration to reschedule a particular substance, which may prompt an FDA review of its current state in research.

Potential for gatekeeping

As clinical trials continue to unveil exciting possibilities, some stakeholders are already trying to monopolize psychedelics through patents, both for the compounds themselves and for the therapeutic practices of producing or administering them. This has ignited criticism from medical and legal experts as well as Indigenous communities, some of which have used certain psychedelics for hundreds (possibly even thousands) of years, the authors of the

Nature Medicine paper explain.

“Restricting patents on psychedelics may be necessary to promote their role in the meaningful advancement of mental health care,” they write.

“U.S. law prohibits patents on products of nature…. Some might also think of psychedelics as tools of discovery that should be free to all and reserved exclusively to none.”

Need for professional, standardized training

New and exciting courses related to psychedelic-assisted therapy training, such as the course provided by MAPS, are on the rise—but not without a few challenges.

“There are training programs that have started but, because the treatments aren’t FDA approved and because the credentialing for this profession has not been established yet, there is nobody to accredit those programs,” Dr. Davis explains.

Currently that means there are no “standards” for training, he says—which is vital for high-quality administration of any drug. For psychedelics, specialized training will help ensure a consistent therapeutic approach, safe and ethical practices, and culturally sensitive care, one 2021

study that explored a training program for psilocybin-assisted therapy concluded.

“Eventually, when the FDA approves these treatments, there will then be a creation of an accreditation body,” Dr. Davis says.

“Then there will be an establishment of what constitutes adequate training and expertise.”

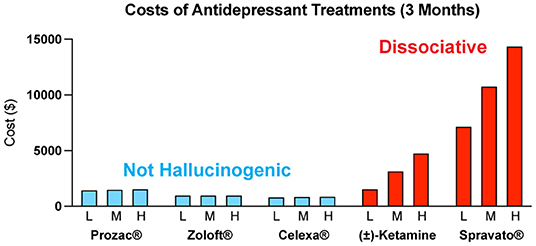

Necessary insurance coverage

Those who stand to benefit from psychedelic-assisted therapy the most will likely be those who lack access, possibly due to socioeconomic barriers like insurance coverage. When—not if—these therapies become legal, they’re likely to be very expensive. Estimates for a future course of MDMA-assisted treatment, for example, hover around $15,000, according to a 2021 research paper published in

Harm Reduction Journal. Experts theorize that establishing a clear prescription model—meaning psychedelic-assisted therapies would require a licensed prescriber like a physician—could help circumvent this issue. But that roadmap may not be the best approach for everyone as discussions around who should be eligible to administer these drugs continue.

Even with these challenges, one hurdle the scientific community continues to face is lifting the stigma surrounding these drugs. The psychedelic renaissance is really a return to decades-old research and even older traditional spiritual practices. We have a long way to go before they become widely accepted, but we’re getting closer with each clinical trial.

“I believe very strongly that education will lift the stigma and improve access, whatever that looks like, quicker than anything else will,” Dr. Strause says.

“And I do believe that the word is getting out.”

How mushrooms, LSD, MDMA, and ketamine could help treat mental illnesses.

www.self.com