How psychedelics impact headaches

by Uri Shine | PsyTech | 29 May 2022

The potential for psychedelics to treat mental health is no longer a secret held by counterculturalists and underground therapists. Research from top universities has established the benefits of psychedelics for

depression,

addiction,

PTSD,

end-of-life care, and much more. But in an interesting side note,

recent research shows that psychedelics users are significantly more likely to have greater overall physical health.

What, if anything, can we read into this?

A connection to general health?

It’s important to remember that correlation does not establish causation. In this context, psychedelic users being more physically healthy does not necessarily suggest that psychedelics were the direct cause of the improvement. It could be that those who are more health-conscious would be more likely to stumble upon and try psychedelics. Similarly,

recent research indicates that the insights people gain from psychedelics may lead them to adopt a healthier lifestyle.

The mind and body exist in a closed circuit. All illness is going to involve physical symptoms that manifest in our consciousness. Treatments at the physical level have effects at the psychological level, and vice versa.

Having said that, a growing number of studies point to the effectiveness of psychedelics in treating various physical ailments that people do not usually associate with the psychological, such as headaches.

Psychedelics treating inflammatory conditions

Inflammation is the body’s natural mechanism to protect us from harm. The process involves increased blood flow, proteins, and antibodies to the area of injury. Although the inflammatory response is critical to survival during injury,

research has revealed that certain lifestyle factors including smoking, obesity, and chronic stress can lead to chronic inflammation (CI) which in turn can result in a wide array of serious diseases including cancer, cardiovascular disease, and autoimmune and neurodegenerative disorders.

For that reason, it is particularly exciting that researchers have discovered evidence that psychedelics have

potent anti-inflammatory properties. In fact, certain drugs targeting 5HT2A receptors (as psychedelics do) seem effective in treating a wide range of inflammatory conditions in rats, including asthma and coronary artery disease.

In addition, researchers have completed phase 1 clinical trials on psychedelics to treat Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases using LSD, thanks to its anti-inflammatory properties.

The study demonstrated the safety and tolerability of 5-20 μg LSD in older healthy individuals.

Building upon these findings, researchers, in conjunction with the life sciences company

Eleusis, are developing new drugs that act on the 5HT2A receptor to treat inflammatory conditions, yet which do not affect behavior. These findings stand to help treat a wide array of physical ailments associated with inflammation.

Psychedelics and Migraine Headaches

According to the

Migraine Research Foundation, migraines are the third most prevalent and sixth most disabling illness in the world, affecting 12% of the population. Over 90% of sufferers are unable to work or function normally during a migraine. Researchers estimate the annual lost productivity costs of migraines in the U.S. at around $36 billion.

For years, anecdotal evidence has suggested that psychedelics can be effective in treating migraines. The first ever clinical trial to study psychedelics for migraines emerged

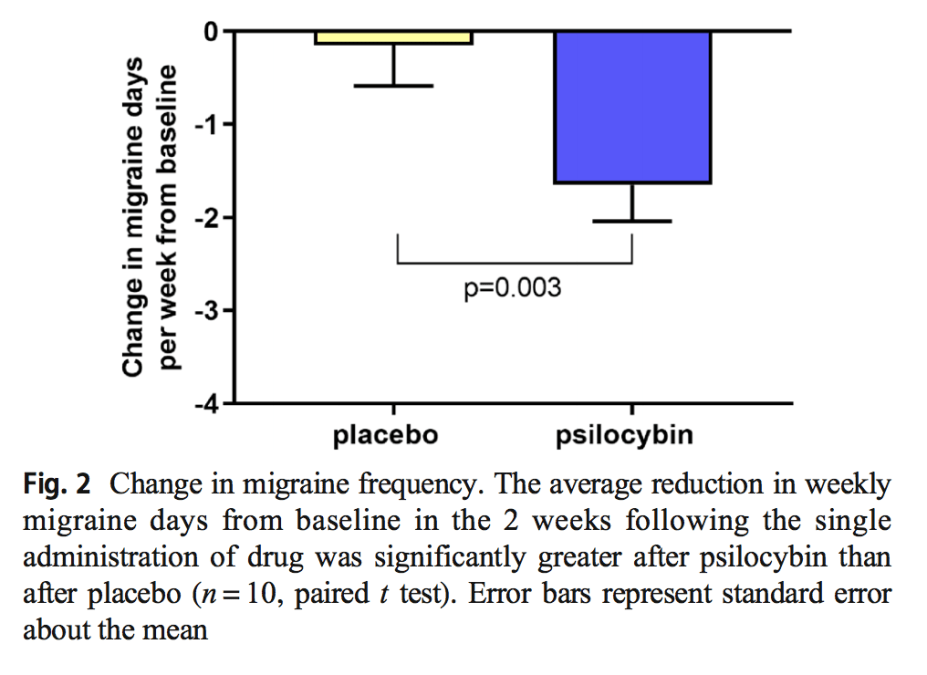

earlier this year. Researchers from the Yale School of Medicine administered a low dose of psilocybin to 10 patients suffering from frequent migraines.

Those who took psilocybin experienced a significant reduction in the frequency of migraines over a 2-week period. Furthermore, psilocybin users had significantly reduced migraine-induced pain and functional impairments.

Psychedelics and Cluster Headaches

Cluster headaches (CH) can be some of the most painful experiences possible. Patients experience cluster periods, generally lasting between weeks and months, during which headaches usually occur every day or even multiple times a day. Each attack typically lasts between 15 minutes and 3 hours. Unsurprisingly, CH patients very often experience chronic depression, anxiety, and PTSD. The causes of CH remain largely unknown and there is no cure.

Like migraines, anecdotal evidence of the efficacy of psychedelics to treat CH drove initial research. In 2006, researchers

published a study in which they surveyed 53 patients about their use of psychedelics to treat their CH. The results were overwhelmingly positive. 85% of patients found psilocybin effective in aborting attacks. 88% of patients found LCD effective in terminating their CH episode. Finally, LCD and psilocybin were very effective at extending patients’ remission periods (80% and 91% respectively).

No other preventative medication has achieved results as positive. Quoting

a qualitative study, CH patients who use LSD “often experience full remission… and can potentially CURE cluster headaches!” Subsequently, Yale University is close to completing the first ever controlled clinical trial to validate these findings.

How do psychedelics treat Headache Disorders?

Both CH and migraine are headache disorders, or neurological conditions characterized by recurrent attacks. They do not seem to be rooted in the psychological realm. Yet psychedelics present great promise in providing effective treatment for these debilitating illnesses.

The causes of headache disorders are not wholly understood. Studies such as

this one have identified multiple brain regions to be involved in producing and maintaining headache attacks. It is therefore unsurprising that the mechanism of action of psychedelics to treat headache disorders is not totally clear either. However, in a

lecture on headache disorders given at the recent PsyTech summit, Dr. Emmanuelle Schindler from the Yale School of Medicine suggested the following as areas worth exploring: hypothalamic and hormonal function, inflammatory systems, and circadian rhythms.

Importantly, we need further research to confirm these initial findings – research with larger and more representative sample sizes, longer durations of observation, and more experimentation with different dosages and frequencies of use.

To conclude

There is a plenitude of areas of disease that are worth mentioning here yet as of yet, many lack clinical or animal trials. These include

autoimmune conditions,

brain injury, and

phantom limb pain, among others.

A great deal more research is needed to fully understand the magic of how psychedelics treat both the symptoms and causes of such a wide array of diseases. But what does seem clear is that the benefits of psychedelics for mental health are likely to be just the tip of the iceberg.

Psychedelics' impact on mental health is well documented. Emerging research is proving their benefits to chronic headaches too.

webcache.googleusercontent.com