poledriver

Bluelighter

- Joined

- Jul 21, 2005

- Messages

- 11,543

Drugs policies and electronic music culture

Psychoactive substances are present in some form in nearly every music scene, but images of drug use tend to stick tenaciously to club culture. Every time there has been a moral panic about electronic music culture, it was fuelled by sensationalist news coverage of drug use. For the UK rave scene of the early '90s, it was the prevalence of ecstasy that caught the tabloids' attention; in the US rave scene of the mid-'90s, there was the 1997 exposé by television newsmagazine 20/20 that featured hidden-camera footage of teenaged ravers consuming drugs; at the turn of the century, there was a highly-publicized drug-related death at Hullaballoo, a happy hardcore rave in Toronto; in the last decade or so, there have been several high-profile "molly"-related deaths at EDM festivals like Electric Daisy Carnival. In all of these cases (and many others), the media coverage perpetuated the reputation of electronic dance music culture as a "drug culture," while also serving to justify draconian changes in legislation and law enforcement.

But there are people out there who are trying to change the tide of this discourse. There are drugs policy reformers pushing for a "harm reduction" approach that prioritizes health and safety over prohibition and punishment. There are researchers trying to collect more reliable information on how drugs affect our bodies and how they circulate in the world. Caught in the middle of all this are electronic music promoters like The Warehouse Project, trying to keep their events safe within the constraints of legal-political environments in which very different notions of drug safety apply.

Back in the fall of 2013, there was a cluster of drug-related emergencies at the WHP that resulted in one death. It seems that the victims had taken a "dodgy" batch of ecstasy pills, most likely containing a lesser-known substance called PMA. PMA (Para-Methoxyamphetamine) belongs to the same class as MDMA and has similar serotonergic effects, but it is far stronger and far more toxic at lower dosages. Notably, what made this situation deadly was the lack of reliable information: the victims took what they thought to be reasonable doses of a familiar drug and fell severely ill.

In response to the incident, the WHP's organizers intensified measures they had already been taking to promote drug safety, such as increasing medical and security staff at the venue, upgrading their air conditioning system and distributing free water. But the measure that garnered the most media attention was a sophisticated system of drug testing conducted at their events, targeted towards providing life-saving information to partygoers. This initiative had already been in the works before the incident, in collaboration with the Home Office and Professor Fiona Measham, a widely-published researcher at Durham University specializing in the socio-cultural study of drug use. Her charity, The Loop, provides drugs information, outreach and welfare at nightlife venues and festivals. In addition to this, The Loop has been providing groundbreaking forensic drug-testing services, where drugs present at an event like the WHP can be tested to check for unexpected substances.

The current legal environment makes this sort of on-site drug testing very difficult to do, but Measham and the WHP have succeeded in instituting a system where drugs confiscated by security or police are tested by Measham's team using state-of-the-art technology. If there are any troubling results (like a batch of pills cut with something dangerous), warnings are sent out via the WHP's social media channels.

This is a pioneering initiative for the WHP, but it's not without its risks. The organizers are well aware of the stakes involved in taking any kind of stance that draws attention to drug use at their events: their efforts might be misconstrued as condoning or even facilitating drug use, and there are those in news media and local politics who are eager to make that point.

During a phone interview, WHP co-founder Sacha Lord-Marchionne chooses his words carefully, and understandably so. Before saying anything about the program, he makes a point of articulating the WHP's anti-drugs stance in the plainest terms possible: "We really do not condone the use of drugs. And obviously we run a very, very strict anti-drugs policy on the door and inside the venue." Lord-Marchionne is nonetheless a realist. "We would be morons to think that, no matter what measures we put in place, people aren't going to get drugs into the venue. It's going to happen, and it happens across the country." Lord-Marchionne frames his collaboration with Prof. Measham as what drugs policy reformers would term "harm reduction," a stance that acknowledges the inevitable presence of drug use and seeks to reduce its negative impacts.

Like it or not, electronic music scenes are now tightly bound up in the messy politics of drugs. They're used as scapegoats for broader societal problems with substance abuse. They're invoked as the justification for changes to official drugs policy. They're often targeted by both media and police for negative attention. But they're also drawing the attention of drug reform activists, researchers and healthcare workers, who increasingly see electronic music events as important sites for intervention, education and investigation. Electronic music scenes bear the brunt of repressive measures that are supposed to fix problems far larger (and older) than electronic music culture.

Policy debates and safety strategies may not be as exciting as arguing about, say, annual DJ rankings, but they're important. The consequences of drugs policy are deadly serious, and they impact us in the world of electronic music directly, whether or not we take drugs ourselves. But this isn't just a story of the top-down effects of government policy pummeling a population of passive, helpless partygoers. There are a lot of organizations pushing for drug reform and better public health education in an effort to make partying safer. At the same time, more and more music venues and event organizers are under pressure to "do something" about drug safety at their events, but they struggle under legal-political conditions that render the most effective drug-safety interventions impossible or at least risky to implement. Amidst all of this, clubbers themselves develop their own collective, grassroots strategies for managing the risks associated with drug use—but this has its own risks and pitfalls.

In surveying this complex landscape, it's necessary to look at three levels of action: government drugs policies; the interventions of non-government actors like promoters, researchers and educators; and the experiences of partygoers trying to have fun and enjoy music under shifting conditions.

Drugs policies

Simply put, a drugs policy is a system of principles guiding decisions about laws and regulations that manage substances considered to be dangerous and/or addictive. For example, most state-level drugs policies are targeted towards reduction—that is, the measures they take are intended to reduce the circulation and consumption of drugs. Some even aim at eradication, holding a drug-free world as their imagined goal. Either way, these sorts of policies tend to target either the supply or the demand of drugs. Targeting the supply chain usually involves destroying drug crops and shipments, disrupting smuggling routes and distribution networks, and going after drug dealers. A wide range of measures are associated with reducing demand for drugs, from the criminalization of drug possession to public anti-drug warnings to addiction therapy.

By contrast, a small but growing minority of governments are also exploring decriminalization, legalization and regulation as alternative ways to reduce the dangers stemming from underground drug trade. The difference with these more liberal policies is that they usually prioritize reducing the negative impacts of drug use over the reduction of drug use itself.

Read the full article -

http://www.residentadvisor.net/feature.aspx?2577

Whether we realise it or not, nightclubs are the battleground for a deeply complex social and political issue. In his latest extended feature, Luis-Manuel Garcia looks at the enormous challenges that governments, promoters, educators, researchers and clubbers face in relation to drugs.

Psychoactive substances are present in some form in nearly every music scene, but images of drug use tend to stick tenaciously to club culture. Every time there has been a moral panic about electronic music culture, it was fuelled by sensationalist news coverage of drug use. For the UK rave scene of the early '90s, it was the prevalence of ecstasy that caught the tabloids' attention; in the US rave scene of the mid-'90s, there was the 1997 exposé by television newsmagazine 20/20 that featured hidden-camera footage of teenaged ravers consuming drugs; at the turn of the century, there was a highly-publicized drug-related death at Hullaballoo, a happy hardcore rave in Toronto; in the last decade or so, there have been several high-profile "molly"-related deaths at EDM festivals like Electric Daisy Carnival. In all of these cases (and many others), the media coverage perpetuated the reputation of electronic dance music culture as a "drug culture," while also serving to justify draconian changes in legislation and law enforcement.

But there are people out there who are trying to change the tide of this discourse. There are drugs policy reformers pushing for a "harm reduction" approach that prioritizes health and safety over prohibition and punishment. There are researchers trying to collect more reliable information on how drugs affect our bodies and how they circulate in the world. Caught in the middle of all this are electronic music promoters like The Warehouse Project, trying to keep their events safe within the constraints of legal-political environments in which very different notions of drug safety apply.

Back in the fall of 2013, there was a cluster of drug-related emergencies at the WHP that resulted in one death. It seems that the victims had taken a "dodgy" batch of ecstasy pills, most likely containing a lesser-known substance called PMA. PMA (Para-Methoxyamphetamine) belongs to the same class as MDMA and has similar serotonergic effects, but it is far stronger and far more toxic at lower dosages. Notably, what made this situation deadly was the lack of reliable information: the victims took what they thought to be reasonable doses of a familiar drug and fell severely ill.

In response to the incident, the WHP's organizers intensified measures they had already been taking to promote drug safety, such as increasing medical and security staff at the venue, upgrading their air conditioning system and distributing free water. But the measure that garnered the most media attention was a sophisticated system of drug testing conducted at their events, targeted towards providing life-saving information to partygoers. This initiative had already been in the works before the incident, in collaboration with the Home Office and Professor Fiona Measham, a widely-published researcher at Durham University specializing in the socio-cultural study of drug use. Her charity, The Loop, provides drugs information, outreach and welfare at nightlife venues and festivals. In addition to this, The Loop has been providing groundbreaking forensic drug-testing services, where drugs present at an event like the WHP can be tested to check for unexpected substances.

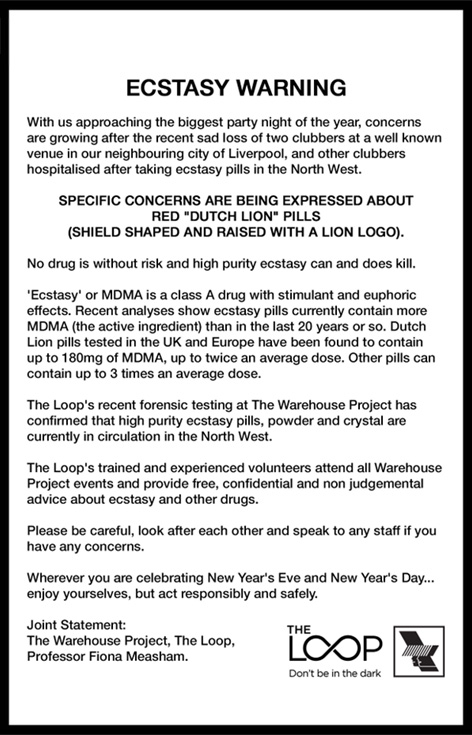

The current legal environment makes this sort of on-site drug testing very difficult to do, but Measham and the WHP have succeeded in instituting a system where drugs confiscated by security or police are tested by Measham's team using state-of-the-art technology. If there are any troubling results (like a batch of pills cut with something dangerous), warnings are sent out via the WHP's social media channels.

This is a pioneering initiative for the WHP, but it's not without its risks. The organizers are well aware of the stakes involved in taking any kind of stance that draws attention to drug use at their events: their efforts might be misconstrued as condoning or even facilitating drug use, and there are those in news media and local politics who are eager to make that point.

During a phone interview, WHP co-founder Sacha Lord-Marchionne chooses his words carefully, and understandably so. Before saying anything about the program, he makes a point of articulating the WHP's anti-drugs stance in the plainest terms possible: "We really do not condone the use of drugs. And obviously we run a very, very strict anti-drugs policy on the door and inside the venue." Lord-Marchionne is nonetheless a realist. "We would be morons to think that, no matter what measures we put in place, people aren't going to get drugs into the venue. It's going to happen, and it happens across the country." Lord-Marchionne frames his collaboration with Prof. Measham as what drugs policy reformers would term "harm reduction," a stance that acknowledges the inevitable presence of drug use and seeks to reduce its negative impacts.

Like it or not, electronic music scenes are now tightly bound up in the messy politics of drugs. They're used as scapegoats for broader societal problems with substance abuse. They're invoked as the justification for changes to official drugs policy. They're often targeted by both media and police for negative attention. But they're also drawing the attention of drug reform activists, researchers and healthcare workers, who increasingly see electronic music events as important sites for intervention, education and investigation. Electronic music scenes bear the brunt of repressive measures that are supposed to fix problems far larger (and older) than electronic music culture.

Policy debates and safety strategies may not be as exciting as arguing about, say, annual DJ rankings, but they're important. The consequences of drugs policy are deadly serious, and they impact us in the world of electronic music directly, whether or not we take drugs ourselves. But this isn't just a story of the top-down effects of government policy pummeling a population of passive, helpless partygoers. There are a lot of organizations pushing for drug reform and better public health education in an effort to make partying safer. At the same time, more and more music venues and event organizers are under pressure to "do something" about drug safety at their events, but they struggle under legal-political conditions that render the most effective drug-safety interventions impossible or at least risky to implement. Amidst all of this, clubbers themselves develop their own collective, grassroots strategies for managing the risks associated with drug use—but this has its own risks and pitfalls.

In surveying this complex landscape, it's necessary to look at three levels of action: government drugs policies; the interventions of non-government actors like promoters, researchers and educators; and the experiences of partygoers trying to have fun and enjoy music under shifting conditions.

Drugs policies

Simply put, a drugs policy is a system of principles guiding decisions about laws and regulations that manage substances considered to be dangerous and/or addictive. For example, most state-level drugs policies are targeted towards reduction—that is, the measures they take are intended to reduce the circulation and consumption of drugs. Some even aim at eradication, holding a drug-free world as their imagined goal. Either way, these sorts of policies tend to target either the supply or the demand of drugs. Targeting the supply chain usually involves destroying drug crops and shipments, disrupting smuggling routes and distribution networks, and going after drug dealers. A wide range of measures are associated with reducing demand for drugs, from the criminalization of drug possession to public anti-drug warnings to addiction therapy.

By contrast, a small but growing minority of governments are also exploring decriminalization, legalization and regulation as alternative ways to reduce the dangers stemming from underground drug trade. The difference with these more liberal policies is that they usually prioritize reducing the negative impacts of drug use over the reduction of drug use itself.

Read the full article -

http://www.residentadvisor.net/feature.aspx?2577