Varieties of Ritual Involving States of Consciousness*

by Ralph Metzner | Journal of Wild Culture | 24 May 2022

A recent contributor to this journal, Ralph Metzner passed away on March 14, at 82. Well known for his controversial studies with Timothy Leary involving LSD at Harvard University, he went on to explore and write about expanded consciousness in many cultures and settings. This essay is his last long published essay. It speaks to what happens when we travel outside our willful, everyday selves, and what can we learn from such journeys, whether they be via the rigour of physical and mental practices or religious and spiritual inspiration, or through the opportunity provided by psychotropic substances for productive self-examination. A pioneer in research into psychedelic experiences and their outcomes, he explains how intentional, altered state journeys in the context of specific rituals can enhance our understanding of the human psyche's ability to heal itself.

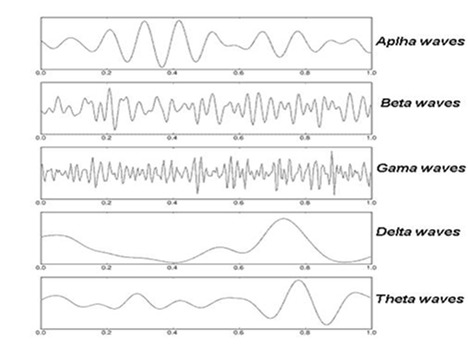

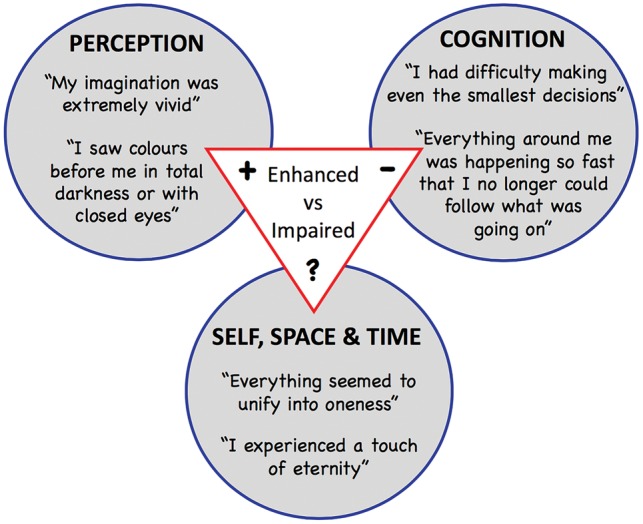

The discovery of psychedelics and the kind of time-limited, yet profoundly altered states of consciousness they induced, has led to a significant re-examination and evaluation of all states of consciousness, both those ordinarily experienced by all, such as waking, sleeping and dreaming, and those less common, induced by such means as psychoactive drugs, hypnosis, shamanic drumming, certain kinds of breathing practices, and others. We recognize some altered states as generally positive, healthy, expansive, and associated with increased knowledge and moral value: this would include religious or mystical experience, ecstasy (lit. “ex-stasis”), transcendence, hypnotherapeutic trance, creative inspiration, tantric erotic trance, shamanic journey, cosmic consciousness, samadhi, nirvana, satori. And there are others generally considered negative, unhealthy, contractive, associated with delusion, psychopathology, destructiveness and even crime, such as depression, rage, psychosis, madness, hysteria, mania, dissociative disorders, substance addictions (alcohol, narcotics, stimulants) and behavioral addictions and fixations (sexuality, violence, gambling, spending). The notion of “altered states” can be considered one paradigm for the study of consciousness.

The research with psychedelic drugs that I participated in with colleagues Tim Leary and Richard Alpert at Harvard University in the early 1960s led to an increased awareness of the importance of intention in understanding states of consciousness. Leary formulated the “set-and-setting” hypothesis, according to which the content of a psychedelic experience is more a function of the intention (set) and the context (setting), than it is a matter of psychopharmacology, i.e., a “drug effect”. The drug is regarded as a trigger, or catalyst, propelling the individual into a different field or state of consciousness, in which the vividness and contextual qualities of sense perceptions are greatly magnified. Other catalysts could be certain foods, fasting, hypnotic inductions, sound, shamanic drumming, breathing (pranayama), trance dance, wilderness isolation, and so forth.

In 'dream incubation', a form of divination, one consciously formulates certain questions . . .

This hypothesis helps one to understand how it is possible that the very same drug, e.g., LSD, was studied and interpreted as a model psychosis (psychotomimetic), an adjunct to psychoanalysis (psycholytic), a treatment for addiction or stimulus to creativity (psychedelic), facilitator of shamanic spiritual insight (entheogenic); or even, as by the US Army and CIA, as a truth-serum type of tool for obtaining secrets fom enemy spies. Of the two factors of set and setting, set, or intention, is clearly primary, since the set ordinarily determines what kind of setting one will choose for the experience.

In my classes, 'Altered States of Consciousness', I have extended the set and setting hypothesis to all alterations of consciousness, no matter by what trigger they are induced; and even those states that recur cyclically and regularly, such as sleeping and waking. In the sleep-waking cycle of alterations of consciousness, internal biochemical events normally trigger the transition to sleeping or waking consciousness; but external factors may provide an additional catalyst. For example, lying in bed, in darkness, triggers changes in melatonin levels in the pineal gland, which in turn triggers falling asleep; and brighter light is normally the trigger for awakening, again meditated by cyclical biochemical changes. There may be, in addition, external factors such as stimulant or sedative drugs, or alarm clocks, which trigger those alterations.

Clearly, the content of our dreams can be analyzed as a function of set, internal factors in our consciousness during the day, as well as the environment in which we find ourselves. In fact, much of psychological dream interpretation is based on the assumption that dreams ofen reflect symbolic processing the prior day’s experiences, i.e., the intention. In dream incubation, a form of divination, one makes deliberate use of that principle, consciously formulating certain questions related to their inner process or outer situation, as one enters the world of sleep dreaming. In hypnotherapy, as in any form of psychotherapy, we always start with the intention or question that the client brings, using that to direct the movement into and through the trance state or the therapeutic session. In shamanic practice, whether with rhythmic drumming as the catalyst, or entheogenic plant concoctions, like ayahuasca, as the preferred method of the practitioner, one always comes initially with a question or intention. Even one’s experience in the ordinary waking state, such as that of the reader perusing this essay, is a function of the internal factors of intention or interest, and the setting where the reading is taking place.

Some researchers, notably Stanislav Grof, in his cartography of altered states, whether induced by psychedelics or by holotropic breathing, have categorized the different states by content, such as perinatal memories, identifications with animals or plants, experiences beyond the ordinary famework of time and space, and so on. Others, including myself, have taken a somewhat different approach, focussing on the energetics of altered states, apart fom content. It is possible to arrange different states of consciousness on a scale of arousal or wakefulness, fom high excitement to sleep or coma; as well as a separate, independent scale of pleasurable, heavenly states vs. painful, hellish states.

A third, purely formal or energetic dimension of altered states, irrespective of content, is expansion vs. contraction. Psychedelic drugs were originally called “consciouness-expanding”: in such states, one does not see hallucinated, illusory objects; rather, one sees the ordinary objects but, in addition, sees, knows and feels associated patterns and aspects that one was not aware of before. In such states, in addition to perception, there is apperception — the reflective awareness of the experiencing subject and understanding of associated elements of context. Another way of saying this is that an objective observer or witness consciousness is added to the subjective experiencing. This expanded awareness, or apperception of context, is generally absent in the psychoactive stimulants and depressants, which simply move consciousness either “up” or “down” on the arousal dimension, and away fom pain or discomfort. The observer witness consciousness is also notoriously absent in the addictive state induced by narcotics, which is typically described as “uncaring”, “cloudy”, or “sleep like.”

Returning for a moment to non-drug alterations of consciousness, we can see that waking up is an experience of expanded consciousness: I become aware of the fact that it is I who is lying in this bed, in this room, having just had this particular dream, and I become aware of the rest of the world outside, with all my relations of family and work, community and cosmos. To transcend means to “go beyond”; therefore, transcendent experiences — variously referred to in the spiritual traditions as enlightenment, awakening, ecstasy, liberation, mystical, cosmic, revelation — all involve an expansion of consciousness in which the previous field of consciousness is not ignored or avoided (we say, “that was only a dream”), but included in a greater context, providing insight.

I have argued, in an essay on “Addiction and Transcendence as Altered States of Consciousness,” that while psychedelic and other forms of transcendent experiences can be regarded as prototypical expansions of consciousness, the prototypical contracted states of consciousness are found in the fixations of addictions, obsessions, compulsions, and attachments. This opposition between them is implied when psychedelic drugs such as LSD and ibogaine are used in the treatment of alcoholism, drug addiction, and other forms of obsessional neurosis. For example, psilocybin, the extracted psychoactive principle of the Mexican sacred mushroom, is now again being tested in the treatment of OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder).

RITUALS ASSOCIATED WITH DRUG CONSUMPTION

I propose the following definition of ritual: Ritual is the purposive, conscious arrangement of time, space, and action, according to specific intentions. In other words, going back to the research with psychedelics, we could say rituals are the conscious arrangement of set and setting. That’s why we had the different fameworks that were used (psychotomimetic, hallucinogenic, psycholytic, psychedelic, entheogenic) according to the predominant mind-set of the people arranging the experience. The particular drug used, LSD, was the same, which shows that the differing experiences were not due to different drug effects.

Young soldiers are taught, in symbolic ritual manoeuvers, how to immunize themselves against ordinary human impulses . . .

The consumption of our most popular psychoactive drugs, the depressant alcohol and the stimulant caffeine, is also surrounded by elaborate rituals, as we know well: the cocktail party, the college beer party, or the ritual brewing of the morning “wake-up” cup of coffee. Researchers in the field of heroin addiction have found that the typical addict is as dependent on the elaborate rituals of preparing for injection as he may be on the drug effect itself. Cigarette smokers, and people watching movies of smokers, know well that the little rituals of taking the cigarette out of the packet, the lighting of the cigarette, for oneself or for others — all seem to be essential elements of the experience that soothes anxiety, overcomes withdrawal distress, and strengthens the habit. One can always ask — what is the intention behind the ritual ingestion? In the case of cigarette smoking the intention appears to be to calm a stress reaction and give oneself a reward.

RITUALS OF EVERYDAY LIFE

We are all familiar with the common little rituals that punctuate transition phases of our everyday existence. In the mornings we have the rituals of the toilet and of cleaning, shaving, dressing and perhaps exercizing. At night time we have the bedtime rituals of putting on night-clothes, stories, prayers, good-night kisses. Parents with small children know how important it ofen is to the child that the exact same sequence of ritual elements is preserved, in order for the child to go peacefully to sleep.

The rituals associated with a family eating together are perhaps the oldest and most venerable in human life, going back to the paleolithic times, when hominid hunters brought back meat fom the hunt to share with the family and tribe. We know as well the rituals of the family meal, and students of family life have pointed out how important the family mealtime can be for the strengthening the family bonds. Or how significant they can be for the development of neurotic disturbances, especially eating disorders, where food ingestion and sharing becomes laden with all kinds of extra emotional baggage, and the taking of food nourishment becomes a substitute for missing emotional nourishment.

It’s not so much the biochemistry of the food and drink that causes difficulties, but the rituals of the family meal that come overlaid with hidden neurotic or power agendas.

Similarly, the activities of mating, sexuality, love, courtship, and marriage are all connected with numerous complex ritual behaviors, some prescribed by tradition and even religious teachings, others determined by glamorized images in novels and films.

Students of the Indian traditions of tantra and of the Chinese sexual teachings of Taoism have re-introduced these ancient teachings into modern life again — practices of ritualizing habitual sexual behavior and elevating to a spiritual practice in its own right — rather than, as is ofen the case in Western Christian-dominated societies, something that is contrary to spirituality. Mircea Eliade, in his work on yoga, referred to tantra as “ritualized physiology.”

INSTITUTIONALIZED RITUALS IN ACADEMIA, RELIGION AND THE MILITARY

Ritualized behavior in academic institutions like this university, are ubiquitous. Typically, in collective ritual activities, there are clearly defined roles for different people to play. For instance, there is the ritual known as the “university lecture,” in which one group of people, called “students,” sit in a more or less receptive mode, listening to an individual called “professor” expounding on a selected topic. The two roles, speaker and audience, carry differing but reciprocal intentions that bring them together into the same setting, at the same time.

Human behavior in church, synagogue or temple is highly ritualized, so much so that for many people the word “ritual” is synonymous with “religious ritual”. Religious rituals, it has ofen been pointed out, can become seemingly empty of meaning, just mechanical repetition of certain words, phrases and gestures. What has happened here? It is when the original spirit or intention behind the religious ritual — which undoubtedly had something to do with connecting with divinity — is no longer alive for those who are leading the rituals, who are therefore unable to convey that spirit to the others. It is as if the ritual form, or ceremonial form, has been emptied of spirit and people then feel bored or uninspired, not moved or uplifted. Some people seem to believe that all kinds of ritual are a good thing, and we need more of them in modern life. However, as can be seen in the example of religious ritual, the moral and social worth of ritual is a function of the intention behind the ritual.

Other areas of social life provide even more dramatic examples of the moral neutrality of ritual. There are rituals of destructiveness and aggressions — ranging all the way fom the ritualized aggression of sports like boxing or football; the fetishistic rituals of sado-masochism and bondage/domination in the sexual arena; to the elaborately choreographed rituals of criminal investigation, policing, the judiciary and the court-room trial; and the dehumanizing training rituals of the military. Young soldiers are taught, in symbolic ritual manoeuvers, how to immunize themselves against ordinary human impulses of decency and kindness, in order to become more ruthless fighting machines or robots. As is well-known, the Nazis were masters of ritual, using the power of uniformed masses of men, with torchlights, songs, marches and propaganda speeches, to accumulate and harness the human energy of zealous devotion to a cause or party for their own in-group economic and power agendas.

HEALING AND THERAPEUTIC RITUALS IN WESTERN MEDICINE & INDIGENOUS SHAMANISM

The ritual aspects of medicine and psychotherapy are well-known and obvious. The practice of medicine is not just the mechanical delivery of drugs or surgery. The way that treatment is presented, whether the physician regards his patient with respect or with condescension, qualities of empathic support and human kindness — are all recognized to be essential elements of the totality of treatment. Good medical training schools will emphasize the importance of a therapeutic “bedside manner” for successful therapeutic outcomes. The holistic medicine movement, in part inspired by Eastern medical traditions such as Chinese, Indian and Tibetan medicine, will consider all aspects of life-style, including diet, exercise, emotional stress, family dynamics and even astrological factors, as part of the overall picture of illness and recovery. These are all aspects of the time and space arrangements, the set and the setting of the interaction between physician and patient.

In the field of psychotherapy, the significance of the contextual ritual is also well appreciated. Psychoanalysis was sometimes called the “talking cure”, but actually, in the writings of Sigmund Freud and his successors, the psychoanalytic healing ritual involved much more than talking. The psychoanalyst sits behind the patient, who is lying on a couch; the latter is instructed to consider the analyst a “blank screen” to which he can communicate his “free associations” — free, that is, of the analysts potentially distracting appearance. One of Freud’s most brilliant and innovative students, Wilhelm Reich, broke with that tradition and invented his own very different therapeutic ritual: facing the patient and observing the breathing movements of his body, he could connect those to psychic content, reading the pattern of muscular tensions he called the “character armor.”

More generally, the importance of a warm, comfortable, safe, aesthetically pleasing setting and empathic manner of the therapist is widely appreciated. These are all factors of ritual, believed to be and chosen to be conducive to positive therapeutic outcomes.

If we compare how Western medicine and psychotherapy have incorporated psychedelic substances into healing practice, with the shamanic healing ceremonies involving entheogenic plant substances, a perception of the importance of ritual is inescapable. The traditional shamanic ceremonial form involving hallucinogenic plants is a carefully structured experience, in which a small group (6-12) of people come together with respectful, spiritual attitude to share a profound inner journey of healing and transformation, facilitated by these powerful catalysts. A "journey" is the preferred metaphor in shamanistic societies for what we call an "altered state of consciousness.”

There are three significant differences between shamanic entheogenic ceremonies and the typical psychedelic psychotherapy. One is that the traditional shamanic rituals involve very little or no talking among the participants, except perhaps during a preparatory phase, or afer the experience to clarify the teachings and visions received. The second is that singing, or the shaman's singing, is invariably considered essential to the success of the healing or divinatory process. Furthermore, the singing typical in etheogenic rituals usually has a fairly rapid beat, similar to the rhythmic pulse in shamanic drumming journeys (widespread in shamanistic societies of the Northern Hemisphere in Asia, Europe, and America). Psychically, the rhythmic chanting, like the drum pulse, seems to give support for moving through the flow of visions and minimize the likelihood of getting stuck in fightening or seductive experiences. The third distinctive feature of traditional ceremonies is that they are almost always done in darkness or low light — which facilitates the emergence of visions. The exception is the peyote ceremony, done around a fire (though also at night); here participants may see visions as they stare into the fire.

I will briefly mention some of the variations on the traditional rituals involving hallucinogens. In the peyote ceremonies of the Native American Church, in North America, participants sit in a circle, in a tipi, on the ground, around a blazing central fire. The ceremony goes all night and is conducted by a "roadman", with the assistance of a drummer, a firekeeper and a cedar-man (for purification). A staff and rattle are passed around and participants sing the peyote songs, which involve a rapid, rhythmic beat. The peyote ceremonies of the Huichol Indians of Northern Mexico also take place around a fire, with much singing and story-telling, afer the long group pilgrimage to find the rare cactus.

The ceremonies of the San Pedro cactus [Echinopsis pachanoi (syn. Trichocereus pachanoi)], in the Andean regions, are sometimes also done around a fire, with singing; but sometimes the curandero [healer or 'medicine man'] sets up an altar, on which are placed different symbolic figurines and objects, representing the light and dark spirits which one is likely to encounter.

The mushroom ceremonies (velada) of the Mazatec Indians of Mexico, involve the participants sitting or lying in a very dark room, with only a small candle. The healer, who may be a woman or a man, sings almost uninterruptedly, throughout the night, weaving into her chants the names of Christian saints, her spirit allies, and the spirits of the Earth, the elements, animals and plants, the sky, the waters and the fire.

Traditional Amazonian Indian or mestizo ceremonies with ayahuasca also involve a small group sitting in a circle, in semi-darkness, while the initiated healers sing the songs (icaros), through which the healing and/or diagnosis takes place. These songs also have a fairly rapid rhythmic pulse, which keeps the flow of the experience moving along. Shamanic "sucking" methods of extracting toxic psychic residues or sorcerous implants are sometimes used.

The ceremonies involving the African iboga plant, used by the Bwiti cult in Gabon amd Zaïre, involve an altar with ancestral and deity images, and people sitting on the floor with much chanting and some dancing. Ofen, there is a mirror in the assembly room, in which the initiates may "see" their ancestral spirits.

In comparing Western psychoactive-assisted psychotherapy with shamanic entheogenic healing rituals, we can see that the role of an experienced guide or therapist is equally central in both, and the importance of set (intention) and setting is implicitly recognized and articulated into the forms of the ritual. The underlying intention in both practices is healing and problem resolution. Therapeutic results can occur with both approaches, though the underlying paradigms of illness and treatment are completely different. The two elements in the shamanic traditions that pose the most direct and radical challenge to the accepted Western worldview are the existence of multiple worlds and of spirit beings; such conceptions are considered completely beyond the pale of both reason and science, though they are taken for granted in the worldview of traditional shamanistic societies.

In both traditional and neo-shamanic practices and ceremonies, there are two main kinds of intention or purpose that are either implicit or often explicitly recognized . . .

It is worth mentioning that in the case of ayahuasca, there have grown in Brazil three distinct syncretic religious movements or churches, that incorporate the taking of ayahuasca into their religious ceremonies as the central sacrament. Here the intention of the ritual is not so much healing or therapeutic insight, as it is strengthening moral values and community bonds. The ceremonial forms here resemble much more the rituals of worship in a church than they resemble either a psychotherapist’s office or a shamanic healing session.

There are also several different kinds of set-and-setting rituals using hallucinogens in the modern West, ranging fom the casual, recreational "tripping" of a few fiends to "rave" events of hundreds or thousands, combining Ecstasy (MDMA) with the continuous rhythmic pulse of techno music. My own research has focussed on what might be called neo-shamanic medicine circles, which represent a kind of hybrid of the psychotherapeutic and traditional shamanic approaches. In the past twenty years or so I have been a participant and observer in over one hundred such circle rituals, in both Europe and North America, involving several hundred participants, many of them repeatedly. Plant entheogens used in these circle rituals have included psilocybe mushrooms, ayahuasca, San Pedro cactus, iboga and others. My interest has focussed on the nature of the psychospiritual transformation undergone by participants in such circle rituals.

In these hybrid therapeutic-shamanic circle rituals certain basic elements fom traditional shamanic healing ceremonies are usually, though not always, kept intact:

• the structure of a circle, with participants either sitting or lying;

• an altar in the center of the circle, or a fire in the center if outside;

• presence of an experienced elder or guide, sometimes with one or more assistants;

• preference for low light, or semi-darkness; sometimes eye-shades are used;

• use of music: drumming, rattling, singing or evocative recorded music;

• dedication of ritual space through invocation of spirits of four directions and elements;

• cultivation of a respectful, spiritual attitude.

Experienced entheogenic explorers understand the importance of set and therefore devote considerable attention to clarifying their intentions with respect to healing and divination. They also understand the importance of setting and therefore devote considerable care to arranging a peaceful place and time, filled with natural beauty and fee fom outside distractions or interruptions.

Most of the participants in circles of this kind that I have observed were experienced in one or more psychospiritual practices, including shamanic drum journeying, Buddhist

vipassana meditation, tantra yoga and holotropic breathwork and most have experienced and/or practiced various forms of psychotherapy and body-oriented therapy. The insights and learnings fom these practices are woven by the participants into their work with the entheogenic medicines. Participants tend to confirm that the entheogenic plant medicines, when combined with meditative or therapeutic insight processes, function to amplify awareness and sensitize perception, particularly amplifying somatic, emotional and instinctual awareness.

Some variation of the talking staff or singing staff is ofen used in such ceremonies: with this practice, which seems to have originated among the Indians of the Pacific Northwest, and is also more generally now referred to as "council", only the person who has the circulating staff sings or speaks, and there is no discussion, questioning or interpretation (as there might be in the usual group psychotherapy formats). Some group sessions, however, involve minimal or no interaction between the participants during the time of the expanded state of consciousness.

In preparation for the circle ritual, there is usually a sharing of intentions and purposes among the participants, as well as the practice of meditation, or sometimes solo time in nature, or expressive arts modalities, such as drawing, painting or journal work. Afer the circle ritual, sometimes the morning afer, there is usually an integration practice of some kind, which may involve participants sharing something of the lessons learned and to be applied in their lives.

RITUALS OF DIVINATION, TRANSITION AND INITIATION

In both traditional and neo-shamanic practices and ceremonies, there are really two main kinds of intention or purpose that are either implicit or, often, explicitly recognized — i.e., healing or problem solving, which usually involve dealing with the past; and seeking guidance or vision, which involve looking at the future. One could say the overall purpose is divination — divination in relationship to healing is called

diagnosis, or seeking the cause of the difficulty. Western medicine and psychotherapy also looks to the past for understanding the causal factors in illness or psychological difficulty: we ask where and how did the wounding, germ, microbe, virus, infection, or familial relationship difficulty begin? Shamanistic healers, for example in South America, are likely, in about 50% of cases, to attribute the origin of both physical and psychic disorders, to sorcery — so the question becomes by whom and how did this hexing take place? Accurate causal diagnosis is recognized as being necessary to determine appropriate and effective treatment or cure. (There are exceptions to this practice: the most striking example is

homeopathy, which merely looks at the pattern of currently manifesting symptoms).

Divination of the future is not generally practiced in Western medicine or psychiatry, except in the somewhat attenuated form that we call

prognosis in medicine.

However, academics, business people, and politicians in the modern world, devote considerable energy and resources to determining future trends and probabilities. Terms such as forecasting, scenario making, computer modeling, trend projections — all indicate a profound interest in probable future possibilities. Terms such as

foresight and

forethought are perhaps the terms most commonly used to describe looking into the future. The profession of psychotherapy has closed itself off fom looking into their clients’ future, largely, I believe, because of an underlying belief that the future can’t be predicted. But this rests on a confusion of foresight with prediction: people practicing future guidance seeking to know the future is probabilistic, not determined, like the past.

One of the ways the newly emerging profession of coaching is distinguishing itself fom traditional psychotherapy by being more concerned with helping clients clearly articulate their intentions for the future and helping them realize them.

Among ordinary people in the Western industrialized nations and even more in Third World countries, it is understood that divination is not like prediction, and at the same time it is understood that the choices we make in the present are greatly influential in bringing about the kind of future we envision. For most people, the term “divination” is associated with systems such as astrology, the

I Ching, the Tarot, runes, stones, bones, etc. These may be regarded as divination accessories or tools. If we examine the basic common factor in all these methods is the asking of a question (or stating an intention) which then guides the diviner’s or psychic’s attention and perception. Just as the client’s question or intention determines the course of the psychotherapists or physicians interventions. The practices that I have developed over the past several years I call “alchemical divination” because their focus is on psychospiritual transformation, as symbolized in alchemical language and symbolism. They can be equally applied to past issues and questions of healing, as well as future issues of seeking a vision or guidance for one’s life. These practices are rituals, in their formalized structure of question-and-answer processes, whether done with individuals or in groups. The steps of the ritual, one might say, is purely internal, like a kind of meditation; but the format is similar to what one would expect to see with a Tarot card reader, or crystal ball gazer, or astrologer, where another, presumably neutral person, who presumably is not as overanxious about some outcomes and, and therefore “seeing” with more clarity and less bias.

There are certain differences in shamanic and alchemical divination practices oriented toward the future, fom the kinds of approach to forecasting used by futurists in academia or the business world. Whereas the latter use purely rational, mental processes and statistics to anticipate future trends, shamanic (and by extension alchemical, since alchemy is an outgrown of shamanism) methods usually involve some kind of altered state method, to bring the questioner and/or the diviner into an expanded or heightened state of consciousness, also called “non-ordinary consciousness”, where they can glimpse into the world beyond the here-and-now reality of the ordinary senses.

The seeking of guidance or a vision for one’s life was an essential core element of the passages of adolescence in traditional societies, especially among native North American Indians. The Plains Indians, such as the Sioux, would have their young boys spend several days on a “vision quest” in the mountains or wilderness, fasting and praying for a vision for their life. There would be extensive preparation beforehand and integration aferward by a tribal or familial elder. In recent years the practice of vision question or fasting alone in the wilderness seeking a vision has been brought to many people at various transition points in their life, not only adolescence — transitions such as divorce, job changes, major deaths or losses in the family and so on. One seeks to connect with inner sources of spiritual guidance, and ofen healing as well.

Rites of passage with a spiritual focus have for a long time been absent in the modern world. They’ve been preserved only in very attenuated and simplistic forms such as the rites of confirmation and bar mitzvah in religious communities, which for many adolescents don’t carry much spiritual meaning anymore. Or they may be found, also in greatly desacralized form, in college faternities, and high school graduation ceremonies. Or they may be found, for males especially, in the brutal violence of military boot-camp training, or of street-level gang initiations. Therefore, the re-introduction of such transition rites or rites of passage, like the vision quest. into modern society represents a reconnection to the archaic life-wisdom practices of the ancient world and of indigenous societies and as such presages the possibility of greatly deepened community and social cohesiveness and health.

*From the article (including references) here :

How altered states — combined with the thoughtful arrangement of space, time and intention — can enhance mental health and healing. By the late Ralph Metzner.

www.wildculture.com

www.lucid.news

www.lucid.news